IBM 701

The IBM 701, known as the Defense Calculator while in development, was announced to the public on April 29, 1952, and was IBM’s first commercial scientific computer.[1] Its business computer siblings were the IBM 702 and IBM 650. It was based on the IAS machine.[2]

Description

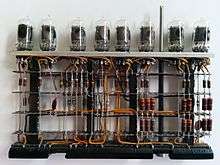

The system used vacuum tube logic circuitry and electrostatic storage, consisting of 72 Williams tubes with a capacity of 1024 bits each, giving a total memory of 2048 words of 36 bits each. Each of the 72 Williams tubes was 3 inches in diameter. Memory could be expanded to a maximum of 4096 words of 36 bits by the addition of a second set of 72 Williams tubes or (later) by replacing the entire memory with magnetic core memory. The Williams tube memory and later core memory each had a memory cycle time of 12 microseconds. The Williams tube memory required periodic refreshing, mandating the insertion of refresh cycles into the 701's timing. An addition operation required five 12-microsecond cycles, two of which were refresh cycles, while a multiplication or division operation required 38 cycles (456 microseconds).

Instructions were 18 bits long, single address.

- Sign (1 bit) - Whole word (-) or Half word (+) operand address

- Opcode (5 bits) - 32 instructions

- Address (12 bits) - 4096 Half word addresses

Numbers were either 36 bits or 18 bits long, signed magnitude, fixed point.

The IBM 701 had only two programmer accessible registers:

- The accumulator was 38 bits long (adding two overflow bits).

- The multiplier/quotient was 36 bits long.

The IBM 701 system was composed of the following units:

- IBM 701 - Analytical Control Unit (CPU)

- IBM 706 - Electrostatic Storage Unit (2048 words of CRT Memory)

- IBM 711 - Punched Card Reader (150 Cards/min.)

- IBM 716 - Printer (150 Lines/min.)

- IBM 721 - Punched Card Recorder (100 Cards/min.)

- IBM 726 - Magnetic Tape Reader/Recorder (100 Bits/inch)

- IBM 727 - Magnetic Tape Reader/Recorder (200 Bits/inch)

- IBM 731 - Magnetic Drum Reader/Recorder

- IBM 736 - Power Frame #1

- IBM 737 - Magnetic Core Storage Unit (4096 words of 12 μs Core Memory)

- IBM 740 - Cathode Ray Tube Output Recorder

- IBM 741 - Power Frame #2

- IBM 746 - Power Distribution Unit

- IBM 753 - Magnetic Tape Control Unit (controlled up to ten IBM 727s)

The Magnetic Drum Reader/Recorder was added on the recommendation of John von Neumann, who said it would reduce the need for high speed I/O.[3]

Nineteen IBM 701 systems were installed.[4] The University of California Radiation Laboratory at Livermore developed a language compilation and runtime system called the KOMPILER for their 701. A Fortran compiler was not released by IBM until the IBM 704.

The 701 can claim to be the first computer displaying the potential of artificial intelligence in Arthur Samuel's Checkers-playing Program.[5]

IBM 701 competed with Remington Rand's ERA 1103 in the scientific computation market, which had been developed for the NSA, so held secret until permission to market it was obtained in 1953. In early 1954, a committee of the Joint Chiefs of Staff requested that the two machines be compared for the purpose of using them for a Joint Numerical Weather Prediction project. Based on the trials, the two machines had comparable computational speed, with a slight advantage for IBM's machine, but the latter was favored unanimously for its significantly faster input-output equipment.[6]

The successor of the 701 was the index register-equipped IBM 704, introduced 4 years after the 701. The 704 was not compatible with the 701, however, as the 704 increased the size of instructions from 18 bits to 36 bits to support the extra features. The 704 also marked the transition to magnetic core memory.

A market for only five computers

"I think there is a world market for maybe five computers" is often attributed to Thomas Watson; Senior in 1943 and Junior at several dates in the 1950s. This misquote is from the 1953 IBM annual stockholders' meeting. Thomas Watson, Jr. was describing the market acceptance of the IBM 701 computer. Before production began, Watson visited with 20 companies that were potential customers. This is what he said at the stockholders' meeting, "as a result of our trip, on which we expected to get orders for five machines, we came home with orders for 18.”[7]

Aviation Week for 11 May 1953 says the 701 rental charge was about $12,000 a month; American Aviation 9 Nov 1953 says "$15,000 a month per 40-hour shift. A second 40-hour shift ups the rental to $20,000 a month."

See also

- IBM 700/7000 series

- List of IBM products

- List of vacuum tube computers

- SHARE (computing)

- Strela computer, comparable Soviet design

References

- ↑ "IBM Archives: IBM 701 Electronic analytical control unit".

- ↑ Turing's Cathedral, by George Dyson, 2012, ISBN 978-1-4000-7599-7, p. 267-68, 287

- ↑ John von Neumann: Selected Letters, Letter to R.S. Burlington, p.73 et seq, Published jointly by the American Mathematical Society and the London Mathematical Society, 2005.

- ↑ "IBM Archives: 701 Customers".

- ↑ Ed Feigenbaum; Gio Wiederhold; John McCarthy (1990). "Memorial Resolution: Arthur L. Samuel" (PDF). Stanford University Historical Society. Retrieved April 29, 2011.

- ↑ Emerson W. Pugh, Lyle R. Johnson, John H. Palmer, IBM's 360 and early 370 systems, MIT Press, 1991, ISBN 0-262-16123-0 pp. 23-34

- ↑ "Frequently Asked Questions" (PDF). IBM. April 10, 2007. p. 26.

- Notes

- Charles J. Bashe, Lyle R. Johnson, John H. Palmer, Emerson W. Pugh, IBM's Early Computers (MIT Press, Cambridge, 1986)

- Cuthbert Hurd (editor), Special Issue: The IBM 701 Thirtieth Anniversary - IBM Enters the Computing Field, Annals of the History of Computing, Vol. 5 (No. 2), 1983

External links

- Oral history interview with Gene Amdahl Charles Babbage Institute, University of Minnesota, Minneapolis. Amdahl discusses his role in the design of several computers for IBM including the IBM 701, the IBM 704 and the STRETCH. He discusses his work with Nathaniel Rochester and IBM's management of the design process for computers.

- A Notable First: The IBM 701

- The Williams Tube

- IBM 701 documents on Bitsavers.org