Ishaq ibn Ibrahim al-Mus'abi

Abu al-Husayn Ishaq ibn Ibrahim[1] (Arabic: أبو الحسين إسحاق بن إبراهيم, died July 850) was a ninth-century official in the service of the Abbasid Caliphate. A member of the Mus'abid family, he was related to the Tahirid governors of Khurasan, and was himself a prominent enforcer of caliphal policy during the reigns of al-Ma'mun, al-Mu'tasim, al-Wathiq, and al-Mutawakkil.[2] In 822 he was appointed as chief of security (shurtah) of Baghdad, and over the next three decades he oversaw many of the major developments in that city, including the implementation of the mihnah or inquisition, the removal of the Abbasid central government to Samarra, and the suppression of the attempted rebellion of Ahmad ibn Nasr al-Khuza'i. After his death, the shurtah of Baghdad briefly remained in the hands of his sons, before being transferred to the Tahirid Muhammad ibn 'Abdallah ibn Tahir in 851.

Early career

Little is known of Ishaq's early life, other than that he possibly born in 793. He first appears[2] in ca. 822 when he was appointed over the shurtah and revenue districts of Baghdad on behalf of his first cousin 'Abdallah ibn Tahir,[3] following the latter's departure to the Jazirah to combat the rebel Nasr ibn Shabath al-Uqayli, and this event marked the beginning of his long career in Baghdad.[4]

Over the next several years Ishaq appears sporadically in the sources. In 825 he housed Nasr ibn Shabath for a short time after the latter had surrendered and was sent to Baghdad, and in 828 he was part of a delegation dispatched by the caliph al-Ma'mun (r. 813–833) to offer 'Abdallah the governorship of Khurasan.[5] According to Ibn al-'Adim, he was briefly made governor of Aleppo, Qinnasrin, the 'awasim and thughur in place of al-Ma'mun's son al-'Abbas in ca. 829, but he was then dismissed and al-'Abbas was restored to those positions.[6]

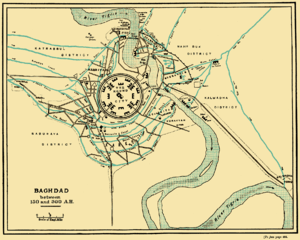

In 830, following al-Ma'mun's decision to go on campaign against the Byzantines, the caliph designated Ishaq as his deputy over Baghdad, and also gave him control over the Sawad, Hulwan, and the Tigris districts. During the last years of al-Ma'mun's reign, Ishaq enforced the caliph's directives in Baghdad while the latter remained away from the city; in 832, for example, he carried out al-Ma'mun's instructions that the garrison troops should begin reciting the takbir when performing the prayers.[7]

In the following year, in order to ensure compliance with the Mu'tazilite doctrine that the Qur'an had been created, al-Ma'mun inaugurated the mihnah or inquisition and ordered Ishaq to implement it in Baghdad. Ishaq accordingly dispatched several individuals to the caliph for questioning and interviewed a number of religious scholars himself, whereupon he received further instructions to punish those who had given unsatisfactory answers. Eventually the majority of the interrogees agreed to state that the Qur'an had been created, but Ahmad ibn Hanbal and Muhammad ibn Nuh al-'Ijli remained steadfast in their opposition and were consequently sent by Ishaq to the caliph in irons.[8]

Under al-Mu'tasim

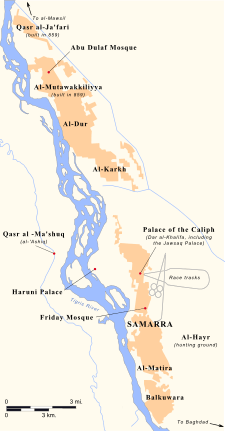

During the reign of al-Ma'mun's successor al-Mu'tasim (r. 833–842), Ishaq served as one of the closest advisors and confidants of the caliph.[9] Following al-Mu'tasim's transfer of his residence, together with the government bureaucracy and army, to his new capital of Samarra in 836, Ishaq was appointed to head the Samarran security (ma'unah) alongside the Turkish officer Itakh,[10] but he also retained his position as chief of the Baghdad shurtah and remained a resident of that city. For the rest of Ishaq's life, Samarra served as the seat of al-Mu'tasim and his successors, while Ishaq himself continued to act as their representative in Baghdad.[11]

Shortly after al-Mu'tasim's accession in August 833, Ishaq was appointed as governor of the Jibal and was ordered to deal with the Khurramites of that region, who had assembled in the district of Hamadhan and defeated a previous army sent against them. Ishaq accordingly selected his brother Tahir to govern the shurtah in his stead and set out for the province. Upon his arrival he was able to achieve a major victory against the Khurramites, reportedly killing tens of thousands of rebels and forcing many others to flee to the Byzantines. After sending a victory dispatch in December 833, he returned to Iraq in May 834, bringing with him a large number of captives and individuals who had received guarantees of safe conduct.[12]

In 838 Ishaq supervised the execution of 'Abdallah, the brother of the defeated Khurramite rebel Babak al-Khurrami, and gibbeted his corpse in Baghdad.[13] In 840 he took into custody Mazyar, the captured rebel prince of Tabaristan, after the latter had arrived in Iraq; upon receiving him, Ishaq ordered him to be transported on an elephant and escorted him to the caliph in Samarra. That same year he formed part of the tribunal that prosecuted the disgraced general al-Afshin, which ended with al-Afshin being found guilty of apostasy and thrown into prison.[14]

Under al-Wathiq

Following the death of al-Mu'tasim in January 842, Ishaq administered the oath of allegiance in Baghdad for his son al-Wathiq (r. 842–847).[15] Under the new caliph, he was called to preside over the cases of several mazalim officials during a general crackdown against the government bureaucracy in 843-4, and in 845 he oversaw the events of the festive season (mawsim) during the annual pilgrimage.[16] That same year he was, according to al-Suli and al-Shabushti, assigned the governorship of Khurasan following the death of 'Abdallah ibn Tahir, but al-Wathiq subsequently changed his mind and canceled the appointment, giving Khurasan to 'Abdallah's son Tahir instead.[17]

Like his two predecessors, al-Wathiq maintained the stance that the Qur'an had been created, and the mihnah continued during his reign. Resistance to these policies in Baghdad eventually culminated in 846, when supporters of orthodoxy led by Ahmad ibn Nasr al-Khuza'i formed plans to launch a popular rebellion against the central government. The conspiracy was discovered, however, prior to the scheduled date of the revolt, and Ahmad was arrested by an agent of Ishaq's brother Muhammad ibn Ibrahim al-Mus'abi (Ishaq himself having been absent from the city at the time of the incident). Ishaq then took part in al-Wathiq's interrogation of the rebel leader in Samarra, and on his orders a number of Ahmad's supporters were rounded up and imprisoned.[18]

Last years and legacy

The accession of al-Mutawakkil (r. 847–861) represented a significant break in the policies and personnel of the central government; not only did the new caliph bring an end to the mihnah and abandon Mu'tazilism, but he also set about removing the senior military and civil officials that had dominated the administrations of his two predecessors. As part of his campaign to weaken the old regime and strengthen his own hold on power, al-Mutawakkil relied on Ishaq to act against those officials who were too strong to be attacked in Samarra itself.[19]

In accordance with his new policy, in 849 the caliph ordered Ishaq to eliminate the powerful chamberlain Itakh, who had left Samarra to go on the pilgrimage that year. On his return journey, Itakh was intercepted by Ishaq and convinced to make a detour to Baghdad; upon his arrival, he was separated from his retinue and detained. He was allowed to die of thirst while held in Ishaq's residence, and his sons remained in prison for the remainder of al-Mutawakkil's reign.[20]

In 850 Ishaq became sick, and he died on July 7 or 8, 850, having designated his son Muhammad ibn Ishaq ibn Ibrahim as his successor. During his final illness he had been visited by al-Mutawakkil's son al-Mu'tazz, the Turkish officer Bugha al-Sharabi, and a contingent of other commanders and soldiers.[21]

In assessing Ishaq's legacy, modern historians generally consider him as being a highly useful and trustworthy servant of the caliphs. His administration of Baghdad is credited as having secured the continued loyalty of the city's residents to the central government, especially after the seat of the caliphs had been moved to Samarra, and he acted as a counterweight to the rising power of the Turkish generals in the capital, a role that his successors would continue to follow after his death. At the same time, he helped to strengthen and maintain the interests of the Tahirids in Iraq, and acted as their agent in exercising influence over the caliphal court. Following his death, the shurtah of Baghdad would remain in the hands of his sons until Muhammad ibn 'Abdallah ibn Tahir took over the position in 851, and the governorship of the city would remain in Tahirid hands until the last decade of the ninth century.[22]

Notes

- ↑ Al-Tabari 1985–2007, v. 33: p. 212.

- 1 2 Turner 2006, p. 402.

- ↑ The relationship between Ishaq and 'Abdallah is based on Ishaq's genealogy as "Ishaq ibn Ibrahim [ibn al-Husayn] ibn Mus'ab;" Daniel 2015; Turner 2006, p. 402. Al-Tabari 1985–2007, v. 32: p. 184; v. 33: p. 3; v. 34: p. 107, etc., consistently refers to Ishaq as "Ishaq ibn Ibrahim ibn al-Mus'ab," leading some scholars (for example Le Strange 1900, p. 119) to refer to him as a cousin of 'Abdallah's father Tahir ibn al-Husayn.

- ↑ Al-Tabari 1985–2007, v. 32: pp. 129, 135; Al-Ya'qubi 1883, p. 574; Turner 2006, p. 402.

- ↑ Al-Tabari 1985–2007, v. 32: pp. 146, 182; Al-Ya'qubi 1883, p. 565.

- ↑ Ibn al-'Adim 1996, p. 40.

- ↑ Al-Tabari 1985–2007, v. 32: pp. 184, 189.

- ↑ Al-Tabari 1985–2007, v. 32: pp. 199 ff.; Al-Ya'qubi 1883, pp. 576-77; Hinds 1993, pp. 2-3.

- ↑ Bosworth 1993, p. 776. An anecdotal example of the close relationship between al-Mu'tasim and Ishaq is provided in Al-Tabari 1985–2007, v. 33: pp. 212 ff.

- ↑ Al-Tabari 1985–2007, v. 34: p. 81.

- ↑ Kennedy 2004, p. 160.

- ↑ Al-Tabari 1985–2007, v. 33: pp. 2-3, 7; Al-Ya'qubi 1883, pp. 575-76.

- ↑ Al-Tabari 1985–2007, v. 33: pp. 88-89; Al-Ya'qubi 1883, p. 579.

- ↑ Al-Tabari 1985–2007, v. 33: pp. 179-80, 185-86 ff.

- ↑ Al-Ya'qubi 1883, p. 585.

- ↑ Al-Tabari 1985–2007, v. 34: pp. 10-11, 21; Al-Ya'qubi 1883, p. 587.

- ↑ Bosworth 1975, p. 101.

- ↑ Al-Tabari 1985–2007, v. 34: pp. 26 ff.; Al-Ya'qubi 1883, p. 589; Hinds 1993, p. 4.

- ↑ Kennedy 2004, pp. 160, 167-68; Turner 2006, p. 402.

- ↑ Al-Tabari 1985–2007, v. 34: pp. 81-82, 83 ff.; Al-Ya'qubi 1883, p. 593.

- ↑ Al-Tabari 1985–2007, v. 34: p. 105; Al-Ya'qubi 1883, p. 595.

- ↑ Kennedy 2004, p. 160; Turner 2006, p. 402; Daniel 2015.

References

- Bosworth, C.E. (1993). "al- Muʿtaṣim Bi 'llāh". The Encyclopedia of Islam, New Edition, Volume VII: Mif–Naz. Leiden and New York: BRILL. p. 776. ISBN 90-04-09419-9.

- Bosworth, C.E. (1975). "The Ṭāhirids and Ṣaffārids". In Frye, R.N. The Cambridge History of Iran, Volume 4: From the Arab Invasion to the Saljuqs. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 90–135. ISBN 0-521-20093-8.

- Daniel, Elton L. (27 September 2015). "Taherids". Encyclopædia Iranica. New York. Retrieved 28 December 2015.

- Hinds, M. (1993). "Mihna". The Encyclopedia of Islam, New Edition, Volume VII: Mif–Naz. Leiden and New York: BRILL. pp. 2–6. ISBN 90-04-09419-9.

- Ibn al-'Adim, Kamal al-Din Abi al-Qasim 'Umar ibn Ahmad ibn Hibat Allah (1996). Zubdat al-Halab min ta'rikh Halab. Beirut: Dar al-Kutub al-'Ilmiyyah.

- Kennedy, Hugh (2004). The Prophet and the Age of the Caliphates: The Islamic Near East from the Sixth to the Eleventh Century (Second ed.). Harlow: Pearson Longman. ISBN 0-582-40525-4.

- Le Strange, Guy (1900). Baghdad During the Abbasid Caliphate: From Contemporary Arabic and Persian Sources. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

- Al-Tabari, Abu Ja'far Muhammad ibn Jarir (1985–2007). Ehsan Yar-Shater, ed. The History of Al-Ṭabarī. 40 vols. Albany, NY: State University of New York Press.

- Turner, John P. (2006). "Ishaq ibn Ibrahim". In Meri, Josef W. Medieval Islamic Civilization: An Encyclopedia, Volume 1, A-K, Index. New York: Routledge. pp. 402–403. ISBN 0-415-96691-4.

- Al-Ya'qubi, Ahmad ibn Abu Ya'qub (1883). Houtsma, M. Th., ed. Historiae, Vol. 2. Leiden: E. J. Brill.

| Preceded by Tahir ibn al-Husayn |

Tahirid governor of Baghdad 822–850 |

Succeeded by Muhammad ibn Ishaq ibn Ibrahim |

.png)