Ishtar Gate

The Ishtar Gate (Arabic: بوابة عشتار, Persian: دروازه ایشتار) was the eighth gate to the inner city of Babylon. It was constructed in about 575 BCE by order of King Nebuchadnezzar II on the north side of the city. It was excavated in the early 20th century and a reconstruction using original bricks is now shown in the Pergamon Museum, Berlin.

History

Dedicated to the Babylonian goddess Ishtar, the gate was constructed using glazed brick with alternating rows of bas-relief mušḫuššu (dragons) and aurochs (bulls), symbolizing the gods Marduk and Adad respectively.[1]

The roof and doors of the gate were of cedar, according to the dedication plaque. The gate was covered in lapis lazuli, a deep-blue semi-precious stone that was revered in antiquity due to its vibrancy. These blue glazed bricks would have given the façade a jewel-like shine. Through the gate ran the Processional Way, which was lined with walls showing about 120 lions, bulls, dragons and flowers on enameled yellow and black glazed bricks, symbolizing the goddess Ishtar. The gate itself depicted only gods and goddesses. These included Ishtar, Adad and Marduk. During celebrations of the New Year, statues of the deities were paraded through the gate and down the Processional Way.

The gate, being part of the Walls of Babylon, was considered one of the original Seven Wonders of the World. It was replaced on that list by the Lighthouse of Alexandria from the third century BC.

Excavation and display

A reconstruction of the Ishtar Gate and Processional Way was built at the Pergamon Museum in Berlin out of material excavated by Robert Koldewey and finished in the 1930s. It includes the inscription plaque. It stands 14 m (46 ft) high and 30 m (100 ft) wide. The excavation ran from 1902 to 1914, and, during that time, 14 m (45 ft) of the foundation of the gate was uncovered.

Claudius James Rich, British resident of Baghdad and a self-taught historian, did personal research on Babylon because it intrigued him. Acting as a scholar and collecting field data, he was determined to discover the wonders to the ancient world. C.J. Rich's topographical records of the ruins in Babylon were the first ever published, in 1815. It was reprinted in England no fewer than three times. C.J. Rich and most other 19th century visitors thought a mound in Babylon was a royal palace, and that was eventually confirmed by Robert Koldewey's excavations, who found two palaces of King Nebuchadnezzar and the Ishtar Gate. Robert Koldewey, a successful German excavator, had done previous work for the Royal Museum of Berlin, with his excavations at Surghul (Ancient Nina) and Al-hiba (ancient Lagash) in 1887. Koldewey's part in Babylon's excavation began in 1899.

The method that the British were comfortable with was excavating tunnels and deep trenches, which was damaging the mud brick architecture of the foundation. Instead, it was suggested that the excavation team focus on tablets and other artefacts rather than pick at the crumbling buildings. Despite the destructive nature of the archaeology used, the recording of data was immensely more thorough than in previous Mesopotamian excavations. Walter Andre, one of Koldewey's many assistants, was an architect and a draftsman, the first at Babylon. His contribution was documentation and reconstruction of Babylon. A small museum was built at the site and Andre was the museums first director.

One of most complex and impressive architectural reconstructions in the history of archaeology, was the rebuilding of Babylon's Ishtar gate and processional way in Berlin. Hundreds of crates of glaze brick fragments were carefully desalinated and then pieced together. Fragments were combined with new bricks baked in a specially designed kiln to re-create the correct color and finish. It was a double gate; the part that is shown in the Pergamon Museum today is the smaller, frontal part. The larger, back part was considered too large to fit into the constraints of the structure of the museum; it is in storage.

Parts of the gate and lions from the Processional Way are in various other museums around the world. Only four museums acquired dragons, while lions went to several museums. The Istanbul Archaeology Museum has lions, dragons, and bulls. Ny Carlsberg Glyptotek in Copenhagen, Denmark, has one lion, one dragon and one bull. The Detroit Institute of Arts houses a dragon. The Röhsska Museum in Gothenburg, Sweden, has one dragon and one lion; the Louvre, the State Museum of Egyptian Art in Munich, the Kunsthistorisches Museum in Vienna, the Royal Ontario Museum in Toronto, the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, the Oriental Institute in Chicago, the Rhode Island School of Design Museum, the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston, and the Yale University Art Gallery in New Haven, Connecticut, each have lions. One of the processional lions was recently loaned by Berlin's Vorderasiatisches Museum to the British Museum [2]

A smaller reproduction of the gate was built in Iraq under Saddam Hussein as the entrance to a museum that has not been completed. Damage to this reproduction has occurred since the Iraq war (see Impact of the U.S. military).

Gallery

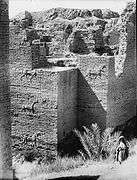

Photo of the remains from the 1930s of the excavation site in Babylon

Photo of the remains from the 1930s of the excavation site in Babylon Model of the main procession street (Aj-ibur-shapu) towards Ishtar Gate

Model of the main procession street (Aj-ibur-shapu) towards Ishtar Gate Model of the gate; the double structure is clearly recognisable.

Model of the gate; the double structure is clearly recognisable.- Aurochs and dragons from the gate in the Istanbul Archaeology Museums

One of the dragons from the gate

One of the dragons from the gate Building inscription of King Nebuchadnezzar II

Building inscription of King Nebuchadnezzar II- Lions and flowers decorated the processional street.

Close-up of an auroch from the Ishtar Gate

Close-up of an auroch from the Ishtar Gate- The replica Ishtar Gate in Babylon in 2004

The replica Ishtar Gate in Babylon, Iraq in 2011

The replica Ishtar Gate in Babylon, Iraq in 2011

References

- ↑ Kleiner, Fred (2005). Gardner's Art Through the Ages. Belmont, CA: Thompson Learning, Inc. p. 49. ISBN 0-15-505090-7.

- ↑ British Museum Website

- Matson, F.R. (1985), Compositional Studies of the Glazed Brick from the Ishtar Gate at Babylon, Museum of Fine Arts. The Research Laboratory, ISBN 0-87846-255-4

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Ishtar Gate. |

- Pictures of lion & dragon at the Röhsska museum, Gothenburg

- Neo-Babylonian Art: Ishtar Gate and Processional Way, Smarthistory

Coordinates: 32°32′36″N 44°25′20″E / 32.54333°N 44.42222°E