Babylon

| بابل | |

A partial view of the ruins of Babylon from Saddam Hussein's Summer Palace | |

Shown within Iraq | |

| Alternate name |

Akkadian: 𒆍𒀭𒊏𒆠, Bābili(m)[1] Sumerian: 𒆍𒀭𒊏𒆠, KÁ.DINGIR.RAKI[1] Hebrew: בָּבֶל, Bavel[1] Greek: Βαβυλών, Babylṓn Old Persian: 𐎲𐎠𐎲𐎡𐎽𐎢, Bābiru Kassite language: Karanduniash |

|---|---|

| Location | Hillah, Babil Governorate, Iraq |

| Region | Mesopotamia |

| Coordinates | 32°32′11″N 44°25′15″E / 32.53639°N 44.42083°ECoordinates: 32°32′11″N 44°25′15″E / 32.53639°N 44.42083°E |

| Type | Settlement |

| Area | 9 km2 (3.5 sq mi) |

| History | |

| Builder | Amorites |

| Founded | 2300 BC |

| Abandoned | 141 BC |

| Site notes | |

| Condition | Ruined |

| Ownership | Public |

| Public access | Yes |

Babylon (𒆍𒀭𒊏𒆠 Akkadian: Bābili or Babilim; Arabic: بابل, Bābil) was a major city of ancient Mesopotamia in the fertile plain between the Tigris and Euphrates rivers. The city was built upon the Euphrates and divided in equal parts along its left and right banks, with steep embankments to contain the river's seasonal floods. Babylon was originally a small Semitic Akkadian city dating from the period of the Akkadian Empire c. 2300 BC.

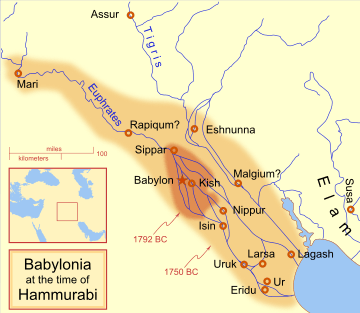

The town attained independence as part of a small city-state with the rise of the First Amorite Babylonian Dynasty in 1894 BC. Claiming to be the successor of the more ancient Sumero-Akkadian city of Eridu, Babylon eclipsed Nippur as the "holy city" of Mesopotamia around the time Amorite king Hammurabi created the first short lived Babylonian Empire in the 18th century BC. Babylon grew and South Mesopotamia came to be known as Babylonia.

The empire quickly dissolved after Hammurabi's death and Babylon spent long periods under Assyrian, Kassite and Elamite domination. After being destroyed and then rebuilt by the Assyrians, Babylon became the capital of the Neo-Babylonian Empire from 609 to 539 BC. The Hanging Gardens of Babylon was one of the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World. After the fall of the Neo-Babylonian Empire, the city came under the rule of the Achaemenid, Seleucid, Parthian, Roman, and Sassanid empires.

It has been estimated that Babylon was the largest city in the world from c. 1770 to 1670 BC, and again between c. 612 and 320 BC. It was perhaps the first city to reach a population above 200,000.[2] Estimates for the maximum extent of its area range from 890[3] to 900 hectares (2,200 acres).[4] The remains of the city are in present-day Hillah, Babil Governorate, Iraq, about 85 kilometres (53 mi) south of Baghdad, comprising a large tell of broken mud-brick buildings and debris.

Name

The English Babylon comes from Greek Babylṓn (Βαβυλών), a transliteration of the Akkadian Babili.[5] The Babylonian name in the early 2nd millennium BC had been Babilli or Babilla, which appears to be an adaption of an unknown original non-Semitic placename.[6] By the 1st millennium BC, it had changed to Babili under the influence of the folk etymology which traced it to bāb-ili ("Gate of God" or "Gateway of the God").[7] The 'Gate of God' or Gate of El being from the Aramaic Hebrew Bab for Gate and El for God, hence Babel. This being similar to the Hebrew word for confusion Balal.[8]

In the Bible, the name appears as Babel (Hebrew: בָּבֶל, Bavel, Tib. בָּבֶל, Bāvel; Syriac: ܒܒܠ, Bāwēl), interpreted in the Hebrew Scriptures' Book of Genesis to mean "confusion",[9] from the verb bilbél (בלבל, "to confuse"). The modern English verb, to "babble", or to speak meaningless words, is popularly thought to derive from this name, but there is no direct connection.[10]

Geography

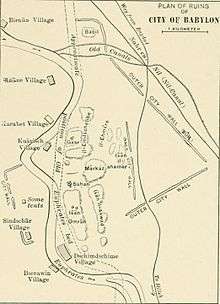

The remains of the city are in present-day Hillah,[5] Babil Governorate, Iraq, about 85 kilometers (53 mi) south of Baghdad, comprising a large tell of broken mud-brick buildings and debris. The site at Babylon consists of a number of mounds covering an area of about 2 by 1 kilometer (1.24 mi × 0.62 mi), oriented north to south, along the Euphrates to the west. Originally, the river roughly bisected the city, but the course of the river has since shifted so that most of the remains of the former western part of the city are now inundated. Some portions of the city wall to the west of the river also remain.

Remains of the city include:

- Kasr—also called Palace or Castle, it is the location of the Neo-Babylonian ziggurat Etemenanki and lies in the center of the site.

- Amran Ibn Ali—the highest of the mounds at 25 meters, to the south. It is the site of Esagila, a temple of Marduk which also contained shrines to Ea and Nabu.

- Homera—a reddish colored mound on the west side. Most of the Hellenistic remains are here.

- Babil—a mound about 22 meters high at the northern end of the site. Its bricks have been subject to looting since ancient times. It held a palace built by Nebuchadnezzar.

Although occupation of the site dates back to the late 3rd millennium, almost nothing from that period has been recovered from prior to the Neo-Babylonian period, for various reasons. The water table in the region has risen greatly over the centuries and artifacts from the time before the Neo-Babylonian Empire are unavailable to current standard archaeological methods. Additionally, the Neo-Babylonians conducted significant rebuilding projects in the city, which destroyed or obscured much of the earlier record. Babylon was pillaged numerous times after revolting against foreign rule, most notably by the Hittites and Elamites in the 2nd millennium, then by the Neo-Assyrian Empire and the Achaemenid Empire in the 1st millennium. Much of the western half of the city is now beneath the river, and other parts of the site have been mined for commercial building materials.

.jpg)

Ancient history

A tablet describing the reign of Sargon of Akkad (c. 23rd century BC short chronology) alludes to the city of Babylon. The so-called Weidner Chronicle states that Sargon had built Babylon "in front of Akkad" (ABC 19:51). Another later chronicle likewise states that Sargon "dug up the dirt of the pit of Babylon, and made a counterpart of Babylon next to Akkad". (ABC 20:18–19). Van de Mieroop has suggested that those sources may refer to the much later Assyrian king Sargon II of the Neo-Assyrian Empire rather than Sargon of Akkad.[11]

Linguist I.J. Gelb, has suggested that the name Babil is in reference to an earlier city name. Herzfeld wrote about Bawer in Ancient Iran, and the name Babil could refer to Bawer. David Rohl holds that the original Babylon is to be identified with Eridu. Joan Oates claims in her book Babylon that the rendering Gateway of the gods is no longer accepted by modern scholars. The Book of Genesis claims that a biblical king named Nimrod was the original founder of Babel (Babylon).

By around the 19th century BC, much of southern Mesopotamia was occupied by Amorites, nomadic tribes from the northern Levant who were Northwest Semitic speakers, unlike the native Akkadians of southern Mesopotamia and Assyria, who were East Semitic speakers. The Amorites at first did not practice agriculture like more advanced Mesopotamians, preferring a semi-nomadic lifestyle, herding sheep. Over time, Amorite grain merchants rose to prominence and established their own independent dynasties in several south Mesopotamian city-states, most notably Isin, Larsa, Eshnunna, Lagash, and later, founding Babylon as a state.

Classical dating

Ctesias, quoted by Diodorus Siculus and in George Syncellus's Chronographia, claimed to have access to manuscripts from Babylonian archives, which date the founding of Babylon to 2286 BC, under the reign of its first king, Belus.[12] A similar figure is found in the writings of Berossus, who according to Pliny,[13] stated that astronomical observations commenced at Babylon 490 years before the Greek era of Phoroneus, indicating 2243 BC. Stephanus of Byzantium wrote that Babylon was built 1002 years before the date given by Hellanicus of Lesbos for the siege of Troy (1229 BC), which would date Babylon's foundation to 2231 BC.[14] All of these dates place Babylon's foundation in the 23rd century BC; however, more recent translation of cuneiform records have not been found to correspond with these classical (post-cuneiform) accounts.

Old Babylonian period

The First Babylonian Dynasty was established by an Amorite chieftain named Sumu-abum in 1894 BC, who declared independence from the neighboring city-state of Kazallu. The Amorites were not native to Mesopotamia, but were semi nomadic Canaanite Northwest Semitic invaders from the northern Levant. They (together with the Elamites to the east) had originally been prevented from taking control of the Akkadian states of southern Mesopotamia by the intervention of powerful Assyrian kings of the Old Assyrian Empire during the 21st and 20th centuries BC, intervening from northern Mesopotamia. However, when the Assyrians turned their attention to expanding their colonies in Asia Minor, the Amorites eventually began to supplant native rulers across the region.

Babylon was initially a minor city state, and controlled little surrounding territory, and its first four Amorite rulers did not even assume the title of king of the city. It remained overshadowed by older and more powerful states such as Assyria, Elam, Isin and Larsa until it became the capital of Hammurabi's short lived Babylonian Empire about a century later. Hammurabi (r. 1792–1750 BC) is famous for codifying the laws of Babylonia into the Code of Hammurabi. He conquered all of the cities and city states of southern Mesopotamia, including Isin, Larsa, Ur, Uruk, Nippur, Lagash, Eridu, Kish, Adab, Eshnunna, Akshak, Akkad, Shuruppak, Bad-tibira, Sippar and Girsu, coalescing them into one kingdom, ruled from Babylon. Hammurabi also invaded and conquered Elam to the east, and the kingdoms of Mari and Ebla to the north west. After a protracted struggle with the powerful Mesopotamian king Ishme-Dagan of Assyria, he forced his successor to pay tribute late in his reign, spreading Babylonian power to Assyria's Hattian and Hurrian colonies in Asia Minor.

After the reign of Hammurabi, the whole of southern Mesopotamia came to be known as Babylonia, whereas the north had coalesced centuries before into Assyria. From this time, Babylon also became the major religious center of Mesopotamia, supplanting the more ancient cities of Nippur and Eridu. Hammurabi's empire destabilized after his death. Assyrians defeated and drove out the Babylonians and Amorites. The far south of Mesopotamia broke away, forming the Sealand Dynasty, and the Elamites appropriated territory in eastern Mesopotamia. The Amorite dynasty remained in power in Babylon, which again became a small city state.

In 1595 BC[16] the city was overthrown by the Hittite Empire from Asia Minor. Thereafter, Kassites from the Zagros Mountains of north western Ancient Iran captured Babylon, ushering in a dynasty that lasted for 435 years, until 1160 BC. The city was renamed Karanduniash during this period. Kassite Babylon eventually became subject to the Middle Assyrian Empire (1365–1053 BC) to the north, and Elam to the east, with both powers vying for control of the city. The Assyrian king Tukulti-Ninurta I took the throne of Babylon in 1235 BC.

By 1155 BC, after continued attacks and annexing of territory by the Assyrians and Elamites, the Kassites were deposed in Babylon. An Akkadian south Mesopotamian dynasty then ruled for the first time. However, Babylon remained weak and subject to domination by Assyria. Its ineffectual native kings were unable to prevent new waves of foreign West Semitic settlers from the deserts of the Levant, including the Arameans and Suteans in the 11th century BC, and finally the Chaldeans in the 9th century BC, entering and appropriating areas of Babylonia for themselves. The Arameans briefly ruled in Babylon during the late 11th century BC.

Assyrian period

During the rule of the Neo-Assyrian Empire (911–609 BC), Babylonia was under constant Assyrian domination or direct control. During the reign of Sennacherib of Assyria, Babylonia was in a constant state of revolt, led by a Chaldean chieftain named Merodach-Baladan, in alliance with the Elamites, and suppressed only by the complete destruction of the city of Babylon. In 689 BC, its walls, temples and palaces were razed, and the rubble was thrown into the Arakhtu, the sea bordering the earlier Babylon on the south. Destruction of the religious center shocked many, and the subsequent murder of Sennacherib by two of his own sons while praying to the god Nisroch was considered an act of atonement. Consequently, his successor Esarhaddon hastened to rebuild the old city and make it his residence during part of the year. After his death, Babylonia was governed by his elder son, the Assyrian prince Shamash-shum-ukin, who eventually started a civil war in 652 BC against his own brother, Ashurbanipal, who ruled in Nineveh. Shamash-shum-ukin enlisted the help of other peoples subject to Assyria, including Elam, Persia, Chaldeans and Suteans of southern Mesopotamia, and the Canaanites and Arabs dwelling in the deserts south of Mesopotamia.

Once again, Babylon was besieged by the Assyrians, starved into surrender and its allies were defeated. Ashurbanipal celebrated a "service of reconciliation", but did not venture to "take the hands" of Bel. An Assyrian governor named Kandalanu was appointed as ruler of the city. After the death of Ashurbanipal, the Assyrian empire destabilized due to a series of internal civil wars throughout the reigns of Assyrian kings Ashur-etil-ilani, Sin-shumu-lishir and Sin-shar-ishkun. Eventually Babylon, like many other parts of the near east, took advantage of the anarchy within Assyria to free itself from Assyrian rule. In the subsequent overthrow of the Assyrian Empire by an alliance of peoples, the Babylonians saw another example of divine vengeance.[17]

Neo-Babylonian Chaldean Empire

Under Nabopolassar, a previously unknown Chaldean chieftain, Babylon eventually escaped Assyrian rule, and in an alliance with Cyaxares, king of the Medes and Persians together with the Scythians and Cimmerians, the Assyrian Empire was finally destroyed between 612 BC and 605 BC. Babylon thus became the capital of the Neo-Babylonian (sometimes and possibly erroneously called Chaldean) Empire.[18][19][20]

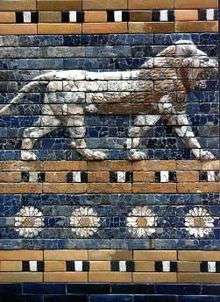

With the recovery of Babylonian independence, a new era of architectural activity ensued, particularly during the reign of his son Nebuchadnezzar II (604–561 BC).[21] Nebuchadnezzar ordered the complete reconstruction of the imperial grounds, including the Etemenanki ziggurat, and the construction of the Ishtar Gate—the most prominent of eight gates around Babylon. A reconstruction of the Ishtar Gate is located in the Pergamon Museum in Berlin.

Nebuchadnezzar is also credited with the construction of the Hanging Gardens of Babylon—one of the seven wonders of the ancient world—which is said to have been built for his homesick wife Amyitis. Whether the gardens actually existed is a matter of dispute. Excavations by German archaeologist Robert Koldewey are thought to reveal its foundations, though many historians disagree about the location, and some believe it may have been confused with gardens in the Assyrian capital, Nineveh.[22]

Chaldean rule of Babylon did not last long; it is not clear whether Neriglissar and Labashi-Marduk were Chaldeans or native Babylonians, and the last ruler Nabonidus (556–539 BC) and his co-regent son Belshazzar were Assyrians from Harran.

Persian conquest

In 539 BC, the Neo-Babylonian Empire fell to Cyrus the Great, king of Persia, with a military engagement known as the Battle of Opis. Babylon's walls were considered impenetrable. The only way into the city was through one of its many gates or through the Euphrates River. Metal grates were installed underwater, allowing the river to flow through the city walls while preventing intrusion. Cyrus (or his generals) devised a plan to enter the city via the river. During a Babylonian national feast, Cyrus' troops diverted the Euphrates River upstream, allowing Cyrus' soldiers to enter the city through the lowered water. The Persian army conquered the outlying areas of the city while the majority of Babylonians at the city center were unaware of the breach. The account was elaborated upon by Herodotus[23] and is also mentioned in parts of the Hebrew Bible.[24][25]

According to 2 Chronicles 36 of the Hebrew Bible, Cyrus later issued a decree permitting captive people, including the Jews, to return to their own lands. Text found on the Cyrus Cylinder has traditionally been seen by biblical scholars as corroborative evidence of this policy, although the interpretation is disputed because the text only identifies Mesopotamian sanctuaries but makes no mention of Jews, Jerusalem, or Judea.

Under Cyrus and the subsequent Persian king Darius the Great, Babylon became the capital city of the 9th Satrapy (Babylonia in the south and Athura in the north), as well as a center of learning and scientific advancement. In Achaemenid Persia, the ancient Babylonian arts of astronomy and mathematics were revitalized, and Babylonian scholars completed maps of constellations. The city became the administrative capital of the Persian Empire and remained prominent for over two centuries. Many important archaeological discoveries have been made that can provide a better understanding of that era.[26][27]

The early Persian kings had attempted to maintain the religious ceremonies of Marduk, but by the reign of Darius III, over-taxation and the strain of numerous wars led to a deterioration of Babylon's main shrines and canals, and the destabilization of the surrounding region. There were numerous attempts at rebellion and in 522 BC (Nebuchadnezzar III), 521 BC (Nebuchadnezzar IV) and 482 BC (Bel-shimani and Shamash-eriba) native Babylonian kings briefly regained independence. However these revolts were quickly repressed and Babylon remained under Persian rule for two centuries, until Alexander the Great's entry in 331 BC.

Hellenistic period

In October of 331 BC, Darius III, the last Achaemenid king of the Persian Empire, was defeated by the forces of the Ancient Macedonian Greek ruler Alexander the Great at the Battle of Gaugamela. A native account of this invasion notes a ruling by Alexander not to enter the homes of its inhabitants.[28]

Under Alexander, Babylon again flourished as a center of learning and commerce. However, following Alexander's death in 323 BC in the palace of Nebuchadnezzar, his empire was divided amongst his generals, the Diadochi, and decades of fighting soon began. The constant turmoil virtually emptied the city of Babylon. A tablet dated 275 BC states that the inhabitants of Babylon were transported to Seleucia, where a palace and a temple (Esagila) were built. With this deportation, Babylon became insignificant as a city, although more than a century later, sacrifices were still performed in its old sanctuary.[29]

Renewed Persian rule

Under the Parthian and Sassanid Empires, Babylon (like Assyria) became a province of these Persian Empires for nine centuries, until after AD 650. It maintained its own culture and people, who spoke varieties of Aramaic, and who continued to refer to their homeland as Babylon. Examples of their culture are found in the Babylonian Talmud, the Gnostic Mandaean religion, Eastern Rite Christianity and the religion of the prophet Mani. Christianity was introduced to Mesopotamia in the 1st and 2nd centuries AD, and Babylon was the seat of a Bishop of the Church of the East until well after the Arab/Islamic conquest.

Muslim conquest

In the mid-7th century, Mesopotamia was invaded and settled by the expanding Muslim Empire, and a period of Islamization followed. Babylon was dissolved as a province and Aramaic and Church of the East Christianity eventually became marginalized.

Modern history

Hussein regime

In 1983, Saddam Hussein began rebuilding the city on top of the old ruins. (Consequently, artifacts and other finds may be under the city.) Hussein invested in both restoration and new construction in Babylon, as well as Ninevah, Nimrud, Assur and Hatra, to demonstrate the magnificence of Arab achievement.[30] He installed a portrait of himself and Nebuchadnezzar at the entrance to the ruins, and reinforced the Processional Way—a large boulevard of ancient stones—and the Lion of Babylon, a black rock sculpture about 2,600 years old. Hussein inscribed his name on many of the bricks, in imitation of Nebuchadnezzar. One frequent inscription reads: "This was built by Saddam Hussein, son of Nebuchadnezzar, to glorify Iraq". These bricks became sought after as collectors' items after Hussein's downfall.

When the Gulf War ended, Hussein wanted to build a modern palace called Saddam Hill over some of the old ruins, in the pyramidal style of a Sumerian ziggurat. In 2003, he intended the construction of a cable car line over Babylon, however plans were halted by the 2003 invasion of Iraq.

Present-day

Following the invasion of Iraq, the area around Babylon came under the control of US troops, before being handed over to Polish forces in September 2003.[31] US forces under the command of General James T. Conway of the 1st Marine Expeditionary Force were criticized for building the military base "Camp Alpha", with a helipad and other facilities on ancient Babylonian ruins following the Iraq War. US forces have occupied the site for some time and have caused irreparable damage to the archaeological record. In a report of the British Museum's Near East department, Dr. John Curtis described how parts of the archaeological site were levelled to create a landing area for helicopters, and parking lots for heavy vehicles. Curtis wrote that the occupation forces:

caused substantial damage to the Ishtar Gate, one of the most famous monuments from antiquity [...] US military vehicles crushed 2,600-year-old brick pavements, archaeological fragments were scattered across the site, more than 12 trenches were driven into ancient deposits and military earth-moving projects contaminated the site for future generations of scientists.[32]

A US Military spokesman claimed that engineering operations were discussed with the "head of the Babylon museum".[33] The head of the Iraqi State Board for Heritage and Antiquities, Donny George, said that the "mess will take decades to sort out" and criticised Polish troops for causing "terrible damage" to the site.[34][35] In 2005 the site was handed over to the Iraqi Ministry of Culture.[31]

In April 2006, Colonel John Coleman, former Chief of Staff for the 1st Marine Expeditionary Force, offered to issue an apology for the damage done by military personnel under his command. However, he also claimed that the US presence had deterred far greater damage by other looters.[36] An article published in April 2006 stated that UN officials and Iraqi leaders have plans to restore Babylon, making it into a cultural center.[37][38] In May 2009, the provincial government of Babil reopened the site to tourism.

Modern research

While historical knowledge of early Babylon must be pieced together from epigraphic remains found elsewhere, such as at Uruk, Nippur, and Haradum, information on the Neo-Babylonian city is available from archaeological excavations and from classical sources. Babylon was described, perhaps even visited, by a number of classical historians including Ctesias, Herodotus, Quintus Curtius Rufus, Strabo, and Cleitarchus. These reports are of variable accuracy and some of the content was politically motivated, but these still provide useful information.[39]

_and_aurochs_on_either_side_of_the_processional_street._Ancient_Babylon%2C_Mesopotamia%2C_Iraq.jpg)

The first reported archaeological excavation of Babylon was conducted by Claudius James Rich in 1811–12 and again in 1817.[40][41] Robert Mignan excavated at the site briefly in 1827.[42] William Loftus visited there in 1849.[43]

Austen Henry Layard made some soundings during a brief visit in 1850 before abandoning the site.[44] Fulgence Fresnel and Julius Oppert heavily excavated Babylon from 1852 to 1854. Unfortunately, much of the result of their work was lost when a raft containing over forty crates of artifacts sank into the Tigris river.[45][46]

Henry Creswicke Rawlinson and George Smith worked there briefly in 1854. The next excavation was conducted by Hormuzd Rassam on behalf of the British Museum. Work began in 1879, continuing until 1882, and was prompted by widespread looting of the site. Using industrial scale digging in search of artifacts, Rassam recovered a large quantity of cuneiform tablets and other finds. The zealous excavation methods, common at the time, caused significant damage to the archaeological context.[47][48]

A team from the German Oriental Society led by Robert Koldewey conducted the first scientific archaeological excavations at Babylon. The work was conducted annually from 1899 until 1917. Primary efforts of the dig involved the temple of Marduk and the processional way leading up to it, as well as the city wall. The Ishtar Gate, along with hundreds of recovered tablets were sent back to Germany.[49][50][51][52][53][54]

Further work by the German Archaeological Institute was conducted by Heinrich J. Lenzen in 1956 and Hansjörg Schmid in 1962. Lenzen's work dealt primarily with the Hellenistic theatre, and Schmid focused on the temple ziggurat Etemenanki.[55]

More recently, the site of Babylon was excavated by G. Bergamini on behalf of the Archaeological Excavations and Research Centre of Turin and the Iraqi-Italian Institute of Archaeological Sciences. This work began with a season of excavation in 1974 followed by a topographical survey in 1977.[56] The focus was on clearing up issues raised by re-examination of the old German data. After a decade, Bergamini returned to the site in 1987–1989. Work at that time concentrated on the area surrounding the Ishara and Ninurta temples in the Shu-Anna city-quarter of Babylon.[57][58]

During the restoration efforts in Babylon, excavation and clearing has also been undertaken by the Iraqi State Organization for Antiquities and Heritage, however wider publication of these archaeological activities has been limited.[59][60]

Cultural importance

Due to Babylon's historical significance as well as references to it in the Bible, the word "Babylon" in various languages has acquired a generic meaning of a large, bustling diverse city. Examples include:

- Babilonas (Lithuanian name for "Babylon")—a real estate development in Lithuania.

- Babylon is used in reggae music as a concept in the Rastafari belief system, denoting the materialistic capitalist world.

- Babylon 5—a science fiction series about a multi-racial futuristic space station.

- Babylon A.D. takes place in New York City, decades in the future.

Biblical narrative

In Genesis 10:10, Babel (Babylon) is described as a neighboring city of Uruk, Akkad and Kalneh, in Shinar.[61]

Babylon appears throughout the Hebrew Bible, including descriptions of the Babylonian Captivity, and also features prominently in several prophecies. The New Testament Book of Revelation refers to Babylon many centuries after it ceased to be a major political center, which some scholars of apocalyptic literature believe to be a dysphemism for the Roman Empire.[62]

See also

- Cities of the ancient Near East

- Etemenanki

- Jehoiachin's Rations Tablets

- Lion of Babylon (statue)

- List of Kings of Babylon

- Tomb of Daniel

- Tower of Babel

References

Citations

- 1 2 3 The Cambridge Ancient History: Prolegomena & Prehistory: Vol. 1, Part 1. Accessed 15 Dec 2010.]

- ↑ Tertius Chandler. Four Thousand Years of Urban Growth: An Historical Census (1987), St. David's University Press ("etext.org". Archived from the original on 2008-02-11. Retrieved 2010-04-18.). ISBN 0-88946-207-0. See Historical urban community sizes.

- ↑ Mieroop, Marc van de (1997). The Ancient Mesopotamian City. Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 95. ISBN 9780191588457.

- ↑ Boiy, T. (2004). Late Achaemenid and Hellenistic Babylon. Orientalia Lovaniensia Analecta. 136. Leuven: Peeters Publishers. p. 233. ISBN 9789042914490.

- 1 2 EB (1878), p. 182.

- ↑ Liane Jakob-Rost, Joachim Marzahn: Babylon, ed. Staatliche Museen zu Berlin. Vorderasiatisches Museum, (Kleine Schriften 4), 2. Auflage, Putbus 1990, p. 2

- ↑ Dietz Otto Edzard: Geschichte Mesopotamiens. Von den Sumerern bis zu Alexander dem Großen, Beck, München 2004, p. 121.

- ↑ BC The Archaeology of the Bible Lands. By Magnus Magnusson. BBC Publications 1977, pages 198-199

- ↑ Gen. 11:9.

- ↑ "Online Etymology Dictionary - babble".

- ↑ Stephanie Dalley, Babylon as a Name for other Cities Including Nineveh, in Uchicago.edu, Proceedings of the 51st Rencontre Assyriologique Internationale, Oriental Institute SAOC 62, pp. 25–33, 2005

- ↑ Records of the Past, Archibald Sayce, 2nd series, Vol. 1, 1888, p. 11.

- ↑ N.H. vii. 57

- ↑ The Seven Great Monarchies of the Ancient Eastern World, George Rawlinson, Vol. 4, p. 526-527.

- ↑ Al-Gailani Werr, L., 1988. Studies in the chronology and regional style of Old Babylonian Cylinder Seals. Bibliotheca Mesopotamica, Volume 23.

- ↑ 1595 BC: Please see Chronology of the ancient Near East for more discussion on dating events in the 2nd millennium BC, including the Sack of Babylon

- ↑ Albert Houtum-Schindler, "Babylon," Encyclopædia Britannica, 11th ed.

- ↑ Bradford, Alfred S. (2001). With Arrow, Sword, and Spear: A History of Warfare in the Ancient World, pp. 47–48. Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN 0-275-95259-2.

- ↑ Curtis, Adrian; Herbert Gordon May (2007). Oxford Bible Atlas Oxford University Press ISBN 978-0-19-100158-1 p. 122 Google Books Search

- ↑ von Soden, Wilfred; Donald G. Schley (1996). William B. Eerdmanns ISBN 978-0-8028-0142-5 p. 60 Google Books Search

- ↑ Saggs, H.W.F. (2000). Babylonians, p. 165. University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-20222-8.

- ↑ Stephanie Dalley, (2013) The Mystery of the Hanging Garden of Babylon: an elusive World Wonder traced, OUP ISBN 978-0-19-966226-5

- ↑ Herodotus, Book 1, Section 191

- ↑ Isaiah 44:27

- ↑ Jeremiah 50–51

- ↑ Cyrus Cylinder The British Museum. Retrieved July 23, 2011.

- ↑ "Mesopotamia: The Persians". Wsu.edu:8080. 1999-06-06. Archived from the original on 6 December 2010. Retrieved 2010-11-09.

- ↑ Beck, Roger B.; Linda Black; Larry S. Krieger; Phillip C. Naylor; Dahia Ibo Shabaka (1999). World History: Patterns of Interaction. Evanston, IL: McDougal Littell. ISBN 0-395-87274-X.

- ↑

Sayce, Archibald Henry (1911). "Babylon". In Chisholm, Hugh. Encyclopædia Britannica. 3 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 98.

Sayce, Archibald Henry (1911). "Babylon". In Chisholm, Hugh. Encyclopædia Britannica. 3 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 98. - ↑ Lawrence Rothfield (1 Aug 2009). The Rape of Mesopotamia: Behind the Looting of the Iraq Museum. University of Chicago Press.

- 1 2 McCarthy, Rory; Kennedy, Maev (2016-05-15). "Babylon wrecked by war". The Guardian. Retrieved 2016-08-20.

- ↑ Bajjaly, Joanne Farchakh (2005-04-25). "History lost in dust of war-torn Iraq". BBC News. Retrieved 2013-06-07.

- ↑ Leeman, Sue (January 16, 2005). "Damage seen to ancient Babylon". The Boston Globe.

- ↑ Marozzi, Justin (2016-08-08). "Lost cities #1: Babylon – how war almost erased 'mankind's greatest heritage site'". The Guardian. Retrieved 2016-08-20.

- ↑ Heritage News from around the world, World Heritage Alert!. Retrieved April 19, 2008.

- ↑ Cornwell, Rupert. US colonel offers Iraq an apology of sorts for devastation of Babylon, The Independent, April 15, 2006. Retrieved April 19, 2008.

- ↑ Gettleman, Jeffrey. Unesco intends to put the magic back in Babylon , International Herald Tribune, April 21, 2006. Retrieved April 19, 2008. Archived June 12, 2006, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ McBride, Edward. Monuments to Self: Baghdad's grands projects in the age of Saddam Hussein , MetropolisMag. Retrieved April 19, 2008. Archived December 10, 2005, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ MacGinnis, John (1986). "Herodotus' Description of Babylon". Bulletin of the Institute of Classical Studies. 33: 67–86. Retrieved 18 March 2015.

- ↑ Claudius J. Rich, Memoirs on the Ruins of Babylon, 1815

- ↑ Claudius J. Rich, Second memoir on Babylon; containing an inquiry into the correspondence between the ancient descriptions of Babylon, and the remains still visible on the site, 1818

- ↑ Google Books Search, Robert Mignan, Travels in Chaldæa, Including a Journey from Bussorah to Bagdad, Hillah, and Babylon, Performed on Foot in 1827, H. Colburn and R. Bentley, 1829 ISBN 1-4021-6013-5

- ↑ Google Books Search, William K. Loftus, Travels and Researches in Chaldaea and Susiana, Travels and Researches in Chaldaea and Susiana: With an Account of Excavations at Warka, the "Erech" of Nimrod, and Shush, "Shushan the Palace" of Esther, in 1849–52, Robert Carter & Brothers, 1857

- ↑ Google Books Search, A. H. Layard, Discoveries in the Ruins of Nineveh and Babylon, J. Murray, 1853

- ↑ J. Oppert, Expédition scientifique en Mésopotamie exécutée par ordre du gouvernement de 1851 à 1854. Tome I: Rélation du voyage et résultat de l'expédition, 1863 (also as ISBN 0-543-74945-2) Tome II: Déchiffrement des inscriptions cuneiforms, 1859 (also as ISBN 0-543-74939-8)

- ↑ H V. Hilprecht, Exploration in the Bible Lands During the 19th Century, A. J. Holman, 1903

- ↑ Archive.org, Hormuzd Rassam, Asshur and the Land of Nimrod: Being an Account of the Discoveries Made in the Ancient Ruins of Nineveh, Asshur, Sepharvaim, Calah, [etc]..., Curts & Jennings, 1897

- ↑ Julian Reade, Hormuzd Rassam and his discoveries, Iraq, vol. 55, pp. 39–62, 1993

- ↑ Google Books Research, R. Koldewey, Das wieder erstehende Babylon, die bisherigen Ergebnisse der deutschen Ausgrabungen, J.C. Hinrichs, 1913, with online English translation: Agnes Sophia Griffith Johns, The excavations at Babylon By Robert Koldewey, Macmillan and Co., 1914

- ↑ R. Koldewey, Die Tempel von Babylon und Borsippa, WVDOG, vol. 15, pp. 37–49, 1911 (German)

- ↑ R. Koldewey, Das Ischtar-Tor in Babylon, WVDOG, vol. 32, 1918

- ↑ F. Wetzel, Die Stadtmauren von Babylon, WVDOG, vol. 48, pp. 1–83, 1930

- ↑ F. Wetzel and F.H. Weisbach, Das Hauptheiligtum des Marduk in Babylon: Esagila und Etemenanki, WVDOG, vol. 59, pp. 1–36, 1938

- ↑ F. Wetzel et al., Das Babylon der Spätzeit, WVDOG, vol. 62, Gebr. Mann, 1957 (1998 reprint ISBN 3-7861-2001-3)

- ↑ Hansjörg Schmid, Der Tempelturm Etemenanki in Babylon, Zabern, 1995, ISBN 3-8053-1610-0

- ↑ G. Bergamini, Levels of Babylon Reconsidered, Mesopotamia, vol. 12, pp. 111–152, 1977

- ↑ G. Bergamini, Excavations in Shu-anna Babylon 1987, Mesopotamia, vol. 23, pp. 5–17, 1988

- ↑ G. Bergamini, Preliminary report on the 1988–1989 operations at Babylon Shu-Anna, Mesopotamia, vol. 25, pp. 5–12, 1990

- ↑ Excavations in Iraq 1981–1982, Iraq, vol. 45, no. 2, pp. 199–224, 1983

- ↑ Farouk N. H. Al-Rawi, Nabopolassar's Restoration Work on the Wall "Imgur-Enlil at Babylon, Iraq, vol. 47, pp. 1–13, 1985

- ↑ "Genesis 10:10 NIV – The first centers of his kingdom were". Bible Gateway. Retrieved 2013-03-25.

- ↑ Merrill Tenney: New Testament Survey, Inter-varsity Press, 1985, pp383

Bibliography

- "Babel", Encyclopædia Britannica, 9th ed., Vol. III, New York: Charles Scribner's Sons, 1878, p. 178.

- Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Babel". Encyclopædia Britannica. 3 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

- "Babylon—Babylonia", Encyclopædia Britannica, 9th ed., Vol. III, New York: Charles Scribner's Sons, 1878, pp. 182–194.

- Sayce, Archibald Henry (1911). "Babylon". In Chisholm, Hugh. Encyclopædia Britannica. 3 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 98–99.

- I.L. Finkel, M.J. Seymour, Babylon, Oxford University Press, 2009 ISBN 0-19-538540-3

- Joan Oates, Babylon, Thames and Hudson, 1986. ISBN 0-500-02095-7 (hardback) ISBN 0-500-27384-7 (paperback)

- The Ancient Middle Eastern Capital City — Reflection and Navel of the World by Stefan Maul ("Die altorientalische Hauptstadt — Abbild und Nabel der Welt," in Die Orientalische Stadt: Kontinuität. Wandel. Bruch. 1 Internationales Kolloquium der Deutschen Orient-Gesellschaft. 9.–1 0. Mai 1996 in Halle/Saale, Saarbrücker Druckerei und Verlag (1997), p. 109–124.

- "UNESCO: Iraq invasion harmed historic Babylon". Associated Press. July 10, 2009.

External links

| Wikivoyage has a travel guide for Babylon. |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Babylon. |

- Babylon on In Our Time at the BBC. (listen now)

- Ancient Babylon

- Iraq Image – Babylon Satellite Observation

- Site Photographs of Babylon – Oriental Institute

- Encyclopædia Britannica, Babylon

- 1901–1906 Jewish Encyclopedia, Babylon

- Beyond Babylon : art, trade, and diplomacy in the second millennium B.C., Issued in connection with an exhibition held Nov. 18, 2008-Mar. 15, 2009, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

- Iraq war

- Babylon wrecked by war, The Guardian, January 15, 2005

- Mirosław Olbryś, The Polish contribution to protection of the archaeological heritage in central south Iraq, November 2003 to April 2005, Conservation and Management of Archaeological Sites, Volume 8, Number 2, 2007 , pp. 88–104(17)

- "Experts: Iraq invasion harmed historic Babylon". Associated Press. July 10, 2009.

- UNESCO Final Report on Damage Assessment in Babylon