John Harvey Kellogg

| John Harvey Kellogg | |

|---|---|

|

Kellogg circa 1913 | |

| Born |

February 26, 1852 Tyrone, Michigan |

| Died |

December 14, 1943 (aged 91) Battle Creek, Michigan |

| Alma mater | New York University Medical College at Bellevue Hospital (M.D., 1875) |

| Occupation | Physician, nutritionist |

| Known for | Battle Creek Sanitarium |

| Religion |

Seventh-day Adventist (until 1907, disfellowed) |

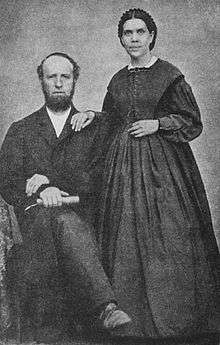

| Spouse(s) | Ella Ervilla Eaton (1853–1920), married 1879 |

| Children | None biological, 8 adopted |

| Parent(s) |

John Preston Kellogg (1806–1881) Ann Janette Stanley (1824–1893) |

| Relatives | Will Keith Kellogg, brother |

| Part of a series on |

| Seventh-day Adventist Church |

|---|

|

|

Adventism Seventh-day Adventist portal |

John Harvey Kellogg, M.D. (February 26, 1852 – December 14, 1943) was an American medical doctor in Battle Creek, Michigan, who ran a sanitarium using holistic methods, with a particular focus on nutrition, enemas, and exercise. Kellogg was an advocate of vegetarianism for health and is best known for the invention of the breakfast cereal known as corn flakes with his brother, Will Keith Kellogg.[1]

He led in the establishment of the American Medical Missionary College. The College, founded in 1895, operated until 1910 when it merged with Illinois State University.

Personal life

Kellogg was born in Tyrone, Michigan,[2] to John Preston Kellogg (1806–1881) and Ann Janette Stanley (1824–1893). John was born in Hadley, Massachusetts and his mother was born in Livingston County, Michigan. Kellogg's ancestry can be traced back to the founding of Hadley, Massachusetts where a great grandfather operated a ferry. Kellogg lived with two sisters during childhood. By 1860, the family had moved to Battle Creek, Michigan, where his father established a broom factory. John later worked as a printer's devil in a Battle Creek publishing house.

Kellogg attended the Battle Creek public schools, then attended the Michigan State Normal School (since 1959, Eastern Michigan University), and finally, New York University School of Medicine. He graduated in 1875 with a medical degree. He married Ella Ervilla Eaton (1853–1920) of Alfred Center, New York, on February 22, 1879. They did not have any biological children, but were foster parents to 42 children, legally adopting eight of them, before Ella died in 1920. The adopted children include Agnes Grace, Elizabeth, John William, Ivaline Maud, Paul Alfred, Robert Mofatt, Newell Carey, and Harriett Eleanor.

In 1937, he received an honorary degree in Doctor of Public Service from Oglethorpe University.[3]

Kellogg died on December 14, 1943 in Battle Creek, Michigan.[1] He was buried in Oak Hill Cemetery, in Battle Creek, Michigan. Among others buried there are his parents, his brother W.K. Kellogg, his brother's wife, James White, Ellen G. White, C. W. Post, Uriah Smith, and Sojourner Truth.

Theological views

A member of the Seventh-day Adventist Church, Kellogg frequently held a prominent role as a speaker at church meetings. He promoted a practical, common sense religion.

Over time, Kellogg began to express panentheistic ideas and some members of the church objected to what he said. At the Seventeenth Annual Session of the General Conference of Seventh-day Adventists, October 4, 1878, the following action was taken:

"WHEREAS, The impression has gone out from some unknown cause that J. H. Kellogg, M.D., holds infidel sentiments, which does him great injustice, and also endangers his influence as physician-in-chief of the Sanitarium; therefore

"[Note.--In accordance with the foregoing resolution, Dr. Kellogg gave, before a large audience, October 6, an able address on the harmony of science and the Bible, for which the congregation tendered him a vote of thanks.]" [4]

"RESOLVED, That in our opinion justice to the doctor and the Institute under his medical charge, demand that he should have the privilege of making his sentiments known, and that he be invited to address those assembled on this ground, upon the harmony of science and the Sacred Scriptures.

"This resolution was unanimously adopted, after which the Conference adjourned to the call of the chair.

At the start of the 20th century, his views of indwelling divinity seemed like panentheism to many other Adventist leaders. As an example of these controversial ideas, at the 1901 General Conference he said:

"Take the sunflower, for example. It looks straight at the sun. It watches and follows the sun all day long, looking straight at it all the time; and as the sun dips down below the horizon, you see that sunflower still looking at it; and as the sun turns around and comes up in the morning, the flower is looking toward the sun rising. It is God in the sunflower that makes it do this…

"Some of you have watched a flower winding up a string, a morning glory winding around a string. Perhaps you have seen a vine climbing up a lattice, and you have watched the end coming out, and turning in, back and forth, between the interstices of the lattice. How does the vine know what to do? There is an intelligence that is present in the plant, in all vegetation…

"The heart is a muscle. The heart beats. My arm will contract and cause the fist to beat; but it beats only when my will commands. But here is a muscle in the body that beats when I am asleep. It beats when my will is inactive and I am utterly unconscious. It keeps on beating all the time. What will is it that causes this heart to beat? The heart can not beat once without a command. To me it is a most wonderful thing that a man's heart goes on beating. It does not beat by means of my will; for I can not stop the heart's beating, or make it beat faster or slower by commanding it by my will. But there is a will that controls the heart. It is the divine will that causes it to beat, and in the beating of that heart that you can feel, as you put your hand upon the breast, or as you put your finger against the pulse, an evidence of the divine presence that we have within us, that God is within, that there is an intelligence, a power, a will within, that is commanding the functions of our bodies and controlling them…" [5]

The issues that had been simmering came to a head in February 1902 when the Battle Creek Sanitarium, owned by the Seventh-day Adventist Church, was destroyed by fire. Ellen G. White told Dr. Kellogg not to rebuild it. He decided to ignore her advice, and was able to gain control of the board of directors. He wrote a book titled The Living Temple which he hoped would pay the costs of reconstruction. When the book was published, it was sharply criticized by Ellen G. White for what she considered to be its many statements of panentheism (God is in everything). In 1907, he was "disfellowshipped".

Battle Creek Sanitarium

Kellogg was a Seventh-day Adventist until mid-life and gained fame while being the chief medical officer of the Battle Creek Sanitarium, which was owned and operated by the Seventh-day Adventist Church. The Sanitarium was run based on the church's health principles. Adventists believe in a vegetarian diet, abstinence from alcohol and tobacco, and a regimen of exercise, which Kellogg followed, among other things. He is remembered as an advocate of vegetarianism[6] and wrote in favor of it, even after leaving the Adventist Church.[7] His dietary advice in the late 19th century, which was in part concerned with reducing sexual stimulation, discouraged meat-eating, but not emphatically so.[8]

Kellogg was an especially strong proponent of nuts, which he believed would save mankind in the face of decreasing food supplies. Though mainly renowned nowadays for his development of corn flakes, Kellogg also patented a process for making peanut butter and invented healthy "granose biscuits."

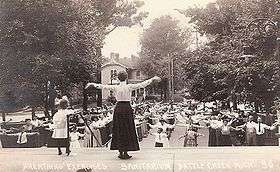

At the Battle Creek Sanitarium, Kellogg held classes on food preparation for homemakers. Sanitarium visitors engaged in breathing exercises and mealtime marches to promote proper digestion of food throughout the day. Because Kellogg was a staunch supporter of phototherapy, the sanitarium also made use of artificial sunbaths.

Kellogg made sure that the bowel of each and every patient was plied with water, from above and below. His favorite device was an enema machine that could rapidly instill several gallons of water in a series of enemas. Every water enema was followed by a pint of yogurt — half was eaten, the other half was administered by enema, “thus planting the protective germs where they are most needed and may render most effective service." The yogurt served to replace the intestinal flora of the bowel, creating what Kellogg claimed was a squeaky-clean intestine.[9]

Kellogg believed that most disease is alleviated by a change in intestinal flora; that bacteria in the intestines can either help or hinder the body; that pathogenic bacteria produce toxins during the digestion of protein that poison the blood; that a poor diet favors harmful bacteria that can then infect other tissues in the body; that the intestinal flora is changed by diet and is generally changed for the better by a well-balanced vegetarian diet favoring low-protein, laxative, and high-fiber foods; and that this natural change in flora could be sped by enemas seeded with favorable bacteria, or by various regimens of specific foods designed to heal specific ailments.

Kellogg was a skilled surgeon, who often donated his services to indigent patients at his clinic.[10] Although generally against unnecessary surgery to treat diseases,[11][12] in his Plain Facts for Old And Young he advocated circumcision as a remedy for "local uncleanliness" (which he thought could lead to "unchastity"),[13] phimosis,[14] and "in small boys", masturbation.[15]

He had many notable patients, such as former president William Howard Taft, composer and pianist Percy Grainger, arctic explorers Vilhjalmur Stefansson and Roald Amundsen, world travellers Richard Halliburton and Lowell Thomas, aviator Amelia Earhart, economist Irving Fisher, Nobel prize winning playwright George Bernard Shaw, actor and athlete Johnny Weissmuller, founder of the Ford Motor Company Henry Ford, inventor Thomas Edison, African American activist Sojourner Truth and actress Sarah Bernhardt.[16] [17][18]

Patents and inventions

Breakfast cereals

John Harvey Kellogg is best known for the invention of the famous breakfast cereal, Corn Flakes, in 1878. Originally, he called this cereal Granula, which he later changed to Granola in 1881. However, due to patent rights, he had to once again change the name to Corn Flakes.[19] These Corn Flakes were invented as part of his health regimen to prevent masturbation. His belief was that bland foods, such as these, would decrease or prevent excitement and arousal.[20]

John Kellogg and his brother Will Keith Kellogg started the Sanitas Food Company to produce their whole grain cereals around 1897, a time when the standard breakfast for the wealthy was eggs and meat, while the poor ate porridge, farina, gruel, and other boiled grains. John and Will later argued over the recipe for the cereals (Will wanted to add sugar to the flakes). So, in 1906, Will started his own company, the Battle Creek Toasted Corn Flake Company, which eventually became the Kellogg Company, triggering a decades-long feud. John then formed the Battle Creek Food Company to develop and market soy products.

A patient of John's, C. W. Post, would eventually start his own dry cereal company, Post Cereals, selling a rival brand of corn flakes. Dr. Kellogg later would claim that Charles Post stole the formula for corn flakes from his safe in the Sanitarium office.

Views on sexuality

As an advocate of sexual abstinence, Kellogg devoted large amounts of his educational and medical work to discouraging sexual activity on the basis of dangers both scientifically understood at the time—as in sexually transmissible diseases—and those taught by the Seventh-day Adventist Church.[21][22][23] He set out his views on such matters in one of his larger books, published in various editions around the start of the 20th century under the title Plain Facts about Sexual Life and later Plain Facts for Old and Young.[8] Some of his work on diet was influenced by his belief that a plain and healthy diet, with only two meals a day, among other things, would reduce sexual feelings. Kellogg was an adherent of the teachings of Sylvester Graham, inventor of the graham cracker, who advocated keeping the diet plain to prevent sexual arousal.[24] Those experiencing temptation were to avoid stimulating food and drinks, and eat very little meat, if any. Kellogg also advocated hydrotherapy and stressed the importance of keeping the colon clean through yogurt enemas.[25][26]

"Warfare with passion"

He warned that many types of sexual activity, including many "excesses" that couples could be guilty of within marriage, were against nature, and therefore, extremely unhealthy. He drew on the warnings of William Acton and expressed support for the work of Anthony Comstock. He appears to have followed his own advice; it has been suggested he worked on Plain Facts during his honeymoon.[27]

He was an especially zealous campaigner against masturbation. This was an orthodox view during his lifetime, especially the earlier part. Kellogg was able to draw upon many medical sources' claims such as "neither the plague, nor war, nor small-pox, nor similar diseases, have produced results so disastrous to humanity as the pernicious habit of onanism," credited to one Dr. Adam Clarke. Kellogg strongly warned against the habit in his own words, claiming of masturbation-related deaths "such a victim literally dies by his own hand," among other condemnations. He felt that masturbation destroyed not only physical and mental health, but the moral health of individuals as well. Kellogg also believed the practice of this "solitary-vice" caused cancer of the womb, urinary diseases, nocturnal emissions, impotence, epilepsy, insanity, and mental and physical debility; "dimness of vision" was only briefly mentioned.

Masturbation prevention

Kellogg worked on the rehabilitation of masturbators, often employing extreme measures, even mutilation, on both sexes. He was an advocate of circumcising young boys to curb masturbation and applying phenol to a young woman's clitoris. In his Plain Facts for Old and Young,[8] he wrote:

| “ | A remedy which is almost always successful in small boys is circumcision, especially when there is any degree of phimosis. The operation should be performed by a surgeon without administering an anesthetic, as the brief pain attending the operation will have a salutary effect upon the mind, especially if it be connected with the idea of punishment, as it may well be in some cases. The soreness which continues for several weeks interrupts the practice, and if it had not previously become too firmly fixed, it may be forgotten and not resumed.[15] | ” |

further

| “ | a method of treatment [to prevent masturbation] ... and we have employed it with entire satisfaction. It consists in the application of one or more silver sutures in such a way as to prevent erection. The prepuce, or foreskin, is drawn forward over the glans, and the needle to which the wire is attached is passed through from one side to the other. After drawing the wire through, the ends are twisted together, and cut off close. It is now impossible for an erection to occur, and the slight irritation thus produced acts as a most powerful means of overcoming the disposition to resort to the practice | ” |

and

| “ | In females, the author has found the application of pure carbolic acid (phenol) to the clitoris an excellent means of allaying the abnormal excitement. | ” |

He also recommended, to prevent children from this "solitary vice", bandaging or tying their hands, covering their genitals with patented cages and electrical shock.[8]

In his Ladies' Guide in Health and Disease, for nymphomania, he recommended

| “ | Cool sitz baths; the cool enema; a spare diet; the application of blisters and other irritants to the sensitive parts of the sexual organs, the removal of the clitoris and nymphae... | ” |

Kellogg thought that masturbation was the worst evil one could commit; he often referred to it as "self-abuse". He was a leader of the anti-masturbation movement, and promoted extreme measures to prevent masturbation.[28][29][30] In addition, Kellogg thought that diet played a huge role in masturbation and that a bland diet would decrease excitability and prevent masturbation. Thus, Kellogg invented Corn Flakes breakfast cereal in 1878. He hoped that feeding children this plain cereal every morning would help to combat the urges of "self-abuse".[31][32][33]

Later life

Kellogg would live for over sixty years after writing Plain Facts. Whether he continued to teach the "facts" in it is not entirely clear, although it appears from the later books he wrote that he moved away from this subject matter. One source, taking a positive view of his nutritional and anti-smoking work, suggests he "dropped his obsession with the evils of sex" around 1920,[34] which would be consistent with the last edition of Plain Facts being apparently published in 1917,[35] but another, highly critical source maintains he "never retracted his claims."[36] He did continue to work on healthy eating advice and run the sanitarium, although this was hit by the Great Depression and had to be sold. He ran another institute in Florida, which was popular throughout the rest of his life,[37] although it was a distinct step down from his Battle Creek institute.[38][39]

Seventh-day Adventists and Ellen G. White

Kellogg took a positive stance toward Seventh-day Adventists and Ellen G. White's prophetic ministry despite earlier struggles. In 1941, in response to critic E. S. Ballenger, Kellogg admonished Ballenger for his critical attitude. "Mrs. White was unquestionably an inspired woman. In spite of this fact, she was human and made many mistakes and probably suffered more from those mistakes than any person ever did. Nevertheless, I knew the woman was sincere and honest and that the influence of her life was immensely helpful to a vast multitude of people, and I have not the slightest desire in any way to weaken in the smallest degree the good influence of her life and work."[40]

Race Betterment Foundation

Kellogg was outspoken on his beliefs on race and segregation, though he himself raised several black foster children. In 1906, together with Irving Fisher and Charles Davenport, Kellogg founded the Race Betterment Foundation, which became a major center of the new eugenics movement in America. Kellogg was in favor of racial segregation and believed that immigrants and non-whites would damage the gene pool.[41]

Relationship with W. K. Kellogg

Kellogg had a long personal and business split with his brother after fighting in court for the rights to cereal recipes. The Foundation for Economic Education records that the nonagenarian J.H.K. prepared a letter seeking to reopen the relationship, but that his secretary decided her employer had demeaned himself in it and refused to send it. The younger Kellogg did not see it until after his brother's death.[39]

Selected publications

- 1877 Plain Facts for Old and Young.

Self Abuse ... After having duly considered the causes and effects of this terrible evil, the question next in order for consideration is, How shall it be cured? When a person has, through ignorance or weakness, brought upon himself the terrible effects described, how shall he find relief from his ills, if restoration is possible? To the answer of these inquiries, most of the remaining pages of this work will be devoted. But before entering upon a description of methods of cure, a brief consideration of the subject of prevention of the habit will be in order.

- 1888 Treatment for Self-Abuse and Its Effects.

- 1893 Ladies Guide in Health and Disease

- 1880, 1886, 1899 The Home Hand-Book of Domestic Hygiene and Rational Medicine

- 1903 Rational Hydrotherapy

- 1910 Light Therapeutics

- 1914 Needed -- A New Human Race Official Proceedings: Vol. I, Proceedings of the First National Conference on Race Betterment. Battle Creek, MI: Race Betterment Foundation, 431-450.

- 1915 "Health and Efficiency" Macmillan M. V. O'Shea and J. H. Kellogg (The Health Series of Physiology and Hygiene)

- 1915 The Eugenics Registry Official Proceedings: Vol II, Proceedings of the Second National Conference on Race Betterment. Battle Creek, MI: Race Betterment Foundation.

- 1922 Autointoxication or Intestinal Toxemia

- 1923 Tobaccoism or How Tobacco Kills

- 1927 New Dietetics: A Guide to Scientific Feeding in Health and Disease

- 1929 Art of Massage: A Practical Manual for the Nurse, the Student and the Practitioner[42]

Popular culture

- T. Coraghessan Boyle's 1993 comic novel The Road to Wellville is a fictionalized story about Kellogg and his sanitarium.

- A filmed version of the book, directed by Alan Parker, was released in 1994. It starred Anthony Hopkins as Kellogg.

- Mel Brooks' 1995 film Dracula: Dead and Loving It featured a sanitarium boss named "Dr. Jack Seward" (played by Harvey Korman), who would recommend enemas for every conceivable ailment. The character was clearly based on Kellogg, and in one scene is seen eating corn flakes. (Dr. Seward is the name of a character in the novel Dracula, by Bram Stoker.)

- The relationship between Kellogg and his brother is depicted in Comedy Central's historical comedy reenactment series Drunk History with Owen Wilson as John Harvey and Luke Wilson as W.K.

See also

References

- 1 2 "J. H. Kellogg Dies; Health Expert, 91.". New York Times. December 16, 1943. Retrieved 2007-10-31.

Dr. John Harvey Kellogg, surgeon, health authority, developer of the Battle Creek Sanitarium and founder of the food business which later became the W. K. Kellogg Company, died here last night at the age of 91, nine years short of the century goal which he had set for himself.

- ↑ While the New York Times obituary for Kellogg gives his place of birth as Tyrone, New York, other reliable sources, including the Battle Creek Historical Society and the 1850 US Census indicate that he was born in Tyrone Township, Livingston County, Michigan.

- ↑ "Honorary Degrees Awarded by Oglethorpe University". Oglethorpe University. Retrieved 2015-03-22.

- ↑ General Conference Committee minutes, October 4, 1878

- ↑ General Conference Bulletin, 34th Session, 1901, Volume 4, No. 2, April 18, p. 491

- ↑ "Dr. John Harvey Kellogg". International Vegetarian Union. Retrieved 2008-04-23.

- ↑ The Simple Life in a Nutshell by J. H. Kellogg

- 1 2 3 4 Kellogg, J.H. (1888). "Treatment for Self-Abuse and Its Effects". Plain Facts for Old and Young. Ayer Publishing. pp. 294–296. ISBN 9780405058080.

- ↑ "Dr. John Harvey Kellogg". www.museumofquackery.com. 2007-10-05. Retrieved 2009-09-20.

- ↑ Biographical sketch. Infoplease.com

- ↑ Kellogg, Dr. John Harvey 1923. Natural Diet of Man

- ↑ Kellogg, Dr. John Harvey 1923. Autointoxication

- ↑ Plain Facts for Old And Young, 1910 ed., p. 234

- ↑ Plain Facts for Old And Young, 1910 ed., p. 355

- 1 2 Plain Facts for Old And Young, 1910 ed., p. 325

- ↑ Rynn Berry, "Famous Vegetarians", Pythagorean Publishers, 2003, pp. 153.

- ↑ Iacobbo & Iacobbo, "Vegetarian America: A History", Praeger, 2009 pp. 130.

- ↑ Margeret Washington, Sojourner Truth's America, University of Illinois Press, 2009 pp. 377

- ↑ Money, John (1985). The Destroying Angel: Sex, fitness, & food in the legacy of degeneracy theory, Graham Crackers, Kellogg's Corn Flakes, & American Health History. New York: Prometheus Books. p. 24.

- ↑ Damour, Lisa; Hansell, James (2008). Abnormal Psychology (2nd ed.). New Jersey: John Wiley & Sons, Inc. p. 368.

- ↑ David F. Horrobin, M.D., Ph.D., Zinc (St. Albans, Vt.: Vitabooks, Inc., 1981), p. 8. See also Carl C. Pfeiffer, Ph.D., M.D., Zinc and Other Micro-Nutrients (New Canaan, Conn.: Keats Publishing, Inc., 1978), p. 45.

- ↑ Richard Nies, Ph.D. (Experimental Psychology, UCLA, 1964; equivalent Ph.D. in clinical psychology, including oral exam, but died during dissertation preparation), Lecture, "Give Glory to God," Glendale, Calif., n.d.; Alberta Mazat, M.S.W. (Professor of Marriage and Family Therapy, Loma Linda University, Loma Linda, Calif.), Monograph, "Masturbation" (43 pp.), Biblical Research Institute.

- ↑ Herbert E. Douglass, Messenger of the Lord: the Prophetic Ministry of Ellen G. White (Nampa, Idaho: Pacific Press Publishing Association, 1998), pp. 493, 494

- ↑ Money, J. (1982). "Sex, Diet, and Debility in Jacksonian America: Sylvester Graham and Health Reform". The Journal of Sex Research. 18 (2): 181–182. doi:10.2307/3812085.

- ↑ Numbers, Ronald L, "Sex, Science, and Salvation: The Sexual Advice of Ellen G. White and John Harvey Kellogg," in Right Living: An Anglo-American Tradition of Self-Help Medicine and Hygiene ed. Charles Rosenberg, 2003., pp. 218-220

- ↑ "John Harvey Kellogg (1852-1943)". CNN. Retrieved May 6, 2010.

- ↑ News of the Odd - John Harvey Kellogg Serves Corn Flakes at the San (March 7, 1897) (Archived December 13, 2007, at the Wayback Machine.)

- ↑ Kellogg, John Harvey (1882). Plain Facts For Old & Young. Iowa: I.F. Segner.

- ↑ Money, John (1985). The Destroying Angel: Sex, Fitness, & Food in the Legacy of Degeneracy Theory, Graham Crackers, Kellogg's Corn Flakes, & American Health History. New York: Prometheus Books. p. 85.

- ↑ Kimmel, Michael (1996). Manhood In America, a cultural history. New York: The Free Press.

- ↑ Kimmel, Michael (1996). Manhood in America, a cultural history. New York: The Free Press. pp. 129–130.

- ↑ Money, John (1985). The Destroying Angel: Sex, Fitness, & Food in the Legacy of Degeneracy Theory, Graham Crackers, Kellogg's Corn Flakes, & American Health History. New York: Prometheus Books. pp. 24, 95.

- ↑ Damour, Lisa; Hansell, James (2008). Abnormal Psychology. New Jersey: John Wiley & Sons, Inc. p. 368.

- ↑ John Harvey Kellogg

- ↑ Google books listing

- ↑ Porn Flakes - John Harvey Kellogg, Sylvester Graham

- ↑ "Kellogg, John Harvey". faqs.org. Retrieved 2008-04-22.

- ↑ "Battle Creek Sanitarium, Early Health Spa". faqs.org. Retrieved 2008-04-22.

- 1 2 "Will Kellogg: King of Corn Flakes". Foundation for Economic Education. April 1998. Retrieved 2016-04-14.

- ↑ "J. H. Kellogg to Church Critics". Retrieved 2014-02-12.

- ↑ See Investigation of Race Betterment Foundation by the Attorney General of Michigan; also see, Ruth C. Engs, Progressive Era's Health Reform, 2003, Greenwood Pub. Co., Race Betterment National Conferences, p. 276

- ↑ John Harvey Kellogg (1996-04-01). Art of Massage: A Practical Manual for the Nurse, the Student and the Practitioner. Kessinger Publishing, LLC. ISBN 1-56459-936-1.

Further reading

- Kellogg, John Harvey (1903). The Living Temple. Battle Creek, Mich., Good Health Publishing Company. 568 pages.

- Deutsch, Ronald M. The Nuts Among the Berries. New York, Ballantine Books, 1961, 1967

- Schwarz, Richard W. John Harvey Kellogg: Pioneering Health Reformer. Hagerstown, MD: Review and Herald, 2006

- Wilson, Brian C. Dr. John Harvey Kellogg and the Religion of Biologic Living. Indianapolis, IN; Indiana University Press, 2014

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to John Harvey Kellogg. |

- Photo Gallery (1000+ images) related to Dr. John Harvey Kellogg and the Battle Creek Sanitarium

- Etext of Plain Facts For Old And Young

- Dr. John Harvey Kellogg and Battle Creek Foods: Work with Soy from the Soy foods Center

- Dr. John Harvey Kellogg from the Battle Creek Historical Society

- Adventist Archives Contains many articles written by Dr. Kellogg

- John Harvey Kellogg: Interview Concerns his dispute with his church in 1907

- Works by John Harvey Kellogg at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about John Harvey Kellogg at Internet Archive

- Works by Ella Ervilla Kellogg at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about Ella Ervilla Kellogg at Internet Archive

- John Harvey Kellogg at Find a Grave

_001.jpg)