Vilhjalmur Stefansson

Vilhjalmur Stefansson (Icelandic: Vilhjálmur Stefánsson) (November 3, 1879 – August 26, 1962) was a Canadian Arctic explorer and ethnologist.

Early life

Stefansson, born William Stephenson, was born at Gimli, Manitoba, Canada, in 1879. His parents had emigrated from Iceland to Manitoba two years earlier. After losing two children during a period of devastating flooding, the family moved to North Dakota in 1880.

He was educated at the universities of North Dakota and of Iowa (A.B., 1903). During his college years, in 1899, he changed his name to Vilhjalmur Stefansson. He studied anthropology at the graduate school of Harvard University, where for two years he was an instructor.

Early explorations

In 1904 and 1905, Stefansson did archaeological research in Iceland. Recruited by Ejnar Mikkelsen and Ernest de Koven Leffingwell for their Anglo-American Polar Expedition, he lived with the Inuit of the Mackenzie Delta during the winter of 1906–1907, returning alone across country via the Porcupine and Yukon Rivers. Under the auspices of the American Museum of Natural History, New York, he and Dr. R. M. Anderson undertook the ethnological survey of the Central Arctic coasts of the shores of North America from 1908 to 1912.

In 1908, Stefansson made a decision that would affect the rest of his time in Alaska: he hired the Inuk guide Natkusiak, who would remain with him as his primary guide for the rest of his Alaska expeditions.[1] At the time he met Natkusiak, the Inuk guide was working for Capt. George B. Leavitt, a Massachusetts whaling ship captain and friend of Stefansson's who sometimes brought the Arctic explorer replenishments of supplies from the American Museum of Natural History.[2]

Christian Klengenberg is first credited to have introduced the term "Blonde Eskimo" to Stefansson just before Stefansson's visit to the Inuit inhabiting southwestern Victoria Island, Canada, in 1910. Stefansson, though, preferred the term Copper Inuit.[3] Adolphus Greely in 1912 first compiled the sightings recorded in earlier literature of blonde or fair haired Arctic natives and in 1912 published them in the National Geographic Magazine entitled "The Origin of Stefansson's Blonde Eskimo". Newspapers subsequently popularised the term "Blonde Eskimo", which caught more readers attention despite Stefansson's preference for Copper Inuit. Stefansson later referenced Greely's work in his writings and the term "Blonde Eskimo" became applied to sightings of light haired Eskimos from as early as the 17th century.[4]

Loss of the Karluk and rescue of survivors

Stefansson organized and directed the Canadian Arctic Expedition 1913-1916 to explore the regions west of Parry Archipelago for the Government of Canada. Three ships, the Karluk, the Mary Sachs, and the Alaska were employed.

Stefansson left the main ship, the Karluk, when it became stuck in the ice in August/September 1913. Stefansson's explanation was that he and five other expedition members left to go hunting to provide fresh meat for the crew. However, William Laird McKinley and others left on the ship suspected that he left deliberately, anticipating that the ship would be carried off by moving ice, as indeed happened. The ship, with Captain Robert Bartlett of Newfoundland and 24 other expedition members aboard, drifted westward with the ice and was eventually crushed. It sank on January 11, 1914. Four men made their way to Herald Island, but died there, possibly from carbon monoxide poisoning, before they could be rescued. Four other men, including Alistair Mackay who had been part of the Sir Ernest Shackleton's British Antarctic Expedition, tried reaching Wrangel Island on their own but perished. The remaining members of the expedition, under command of Captain Bartlett, made their way to Wrangel Island where three died. Bartlett and his Inuk hunter Kataktovik made their way across sea ice to Siberia to get help. Remaining survivors were picked up by the American fishing schooner King & Winge and the U.S. revenue cutter Bear.[5]

Stefansson resumed his explorations by sledge over the Arctic Ocean, here known as the Beaufort Sea, leaving Collinson Point, Alaska in April, 1914. A supporting sledge turned back 75 mi (121 km) offshore, but he and two men continued onward on one sledge, living largely by his rifle on polar game for 96 days until his party reached the Mary Sachs in the autumn. Stefansson continued exploring until 1918.

Wrangel Island fiasco

In 1921, he encouraged and planned an expedition for four young men to colonise Wrangel Island north of Siberia, where the eleven survivors of the 22 men on the Karluk had lived from March to September 1914. Stefansson had designs for forming an exploration company that would be geared towards individuals interested in touring the Arctic island.

Stefansson originally wanted to claim Wrangel Island for the Canadian government. However, due to the dangerous outcome from his initial trip to the island, the government refused to assist with the expedition. He then wanted to claim the land for Britain but the British government rejected this claim when it was made by the young men. The raising of the British flag on Wrangel Island, acknowledged Russian territory, caused an international incident.

The four young men, Frederick Maurer, E. Lorne Knight, and Milton Galle from the US, and Allan Crawford of Canada, were inexperienced and ill-equipped for the trip. All perished on the island or in an attempt to get help from Siberia across the frozen Chukchi Sea. The only survivors were an Inuk woman, Ada Blackjack, whom the men had hired as a seamstress in Nome, Alaska, and taken with them, and the expedition's cat, Vic. Ada Blackjack had taught herself survival skills and cared for the last man on the island, E. Lorne Knight, until he died of scurvy. Blackjack was rescued in 1923 after two years on Wrangel Island. Stefansson drew the ire of the public and the families for having sent such ill equipped young men to Wrangel. His reputation was severely tainted by this disaster and that of the Karluk.

Discoveries

Stefansson's discoveries included new land (such as Brock, Mackenzie King, Borden, Meighen, and Lougheed Islands)[6] and the edge of the continental shelf. His journeys and successes are among the marvels of Arctic exploration. He extended the discoveries of Francis Leopold McClintock. From April 1914 to June 1915 he lived on the ice pack. Stefansson continued his explorations leaving from Herschel Island on August 23, 1915.

In 1921 he was awarded the Founder's Gold Medal of the Royal Geographical Society for his explorations of the Arctic.[7]

Later career

Stefansson remained a well-known explorer for the rest of his life. Late in life, through his affiliation with Dartmouth College (he was Director of Polar Studies), he became a major figure in the establishment of the US Army's Cold Regions Research and Engineering Laboratory (CRREL) in Hanover, New Hampshire. CRREL-supported research, often conducted in winter on the forbidding summit of Mount Washington, has been key to developing matériel and doctrine to support alpine conflict.

Stefansson joined the Explorers Club in 1908, four years after its founding. He later served as Club President twice: 1919–1922 and 1937–1939. In the all-male Club, the Board drew attention under Stefansson's reign when it put forth an amendment to its bylaws that read in 1938, "A Woman's Roll of Honor shall be instituted to which the Board of Directors may name women of the United States and Canada in recognition of the noteworthy achievements and writings in the field of the Club's interests, primarily exploration."[8] Perhaps to comfort fellow members, the article added, "This Woman's Roll of Honor shall be quite outside the Club's organisation but shall correspond in dignity to the Honorary Class of (male) members within it."[8] His continued support of women in anthropology is demonstrated in his mentorship 1939 - 1941 of Gitel Steed as she undertook research on diet and subsistence for his two-volume Lives of the Hunters, from which she began a dissertation on hunter-gatherer.

While living in New York City, Stefansson was one of the regulars at Romany Marie's Greenwich Village cafés.[9] During the years when he and novelist Fannie Hurst were having an affair,[10] they met there when he was in town.

In 1941 he became the third honorary member of the American Polar Society.[11] He served as president of the History of Science Society from 1945-46.[12]

In 1940, he met his future wife Evelyn Schwartz Baird at Romany Marie's;[9][10] Stefansson and Baird married soon after.[13]

Legacy

Stefansson's personal papers and collection of Arctic artifacts are maintained and available to the public at the Dartmouth College Library.

Stefansson is frequently quoted as saying that "adventure is a sign of incompetence."

On May 28, 1986, the United States Postal Service issued a 22 cent postage stamp in his honour.[14]

Political affiliations

In the 1930s, pro-Soviet movements were created whose main aim was to provide support for the Soviet project to establish a Jewish socialist republic in the Birobidzhan region in the far east of the USSR. One of the organisations prominent in this campaign was the American Committee for the Settlement of Jews in Birobidjan, or Ambijan, formed in 1934. A tireless proponent of settlement in Birobidzhan, Stefansson appeared at countless Ambijan meetings, dinners, and rallies, and proved an invaluable resource. Ambijan produced a 50-page Year Book at the end of 1936, full of testimonials and letters of support. Among these was one from Stefansson, who was now also listed as a member of Ambijan's Board of Directors and Governors: "The Birobidjan project seems to me to offer a most statesmanlike contribution to the problem of the rehabilitation of eastern and central European Jewry," he wrote.

Ambijan's national conference in New York, November 25–26, 1944, pledged to raise $1 million to support refugees in Stalingrad and Birobidzhan. Prominent guests and speakers included New York Congressman Emanuel Celler, Senator Elbert D. Thomas of Utah, and Soviet ambassador Andrei Gromyko. A public dinner, attended by the delegates and their guests, was hosted by Vilhjalmur and spouse Evelyn Stefansson. Vilhjalmur was selected as one of two vice-presidents of the organisation.

But with the growing anti-Russian feeling in the country after World War II, "exposés" of Stefansson began to appear in the press. In August 1951, he was denounced as a Communist before a Senate Internal Security subcommittee by Louis F. Budenz, a Communist-turned-Catholic. Perhaps Stefansson himself had by then had some second thoughts about Ambijan, for his posthumously published autobiography made no mention of his work on its behalf. Nor, for that matter, did his otherwise very complete obituary in The New York Times of August 27, 1962.[15]

Low-carbohydrate diet of meat and fish

Stefansson is also a figure of considerable interest in dietary circles, especially those with an interest in very low-carbohydrate diets. Stefansson documented the fact that the Inuit diet consisted of about 90% meat and fish; Inuit would often go 6 to 9 months a year eating nothing but meat and fish—what was perceived to have been a no-carbohydrate diet. He found that he and his fellow explorers of European descent were also perfectly healthy on such a diet. While there was considerable skepticism when he reported these findings, they have been borne out in later studies and analyses.[16] In multiple studies, it was shown that the Inuit diet was a ketogenic diet although a percentage of its calories are derived from the glycogen found in the raw meats, although the native Eskimo diet ate primarily stewed (boiled) fish and meats.[17][18][19] When medical authorities questioned him on his findings, he and a fellow explorer agreed to undertake a study to demonstrate that they could eat a 100% meat diet in a closely observed laboratory setting for the first several weeks, with paid observers for the rest of an entire year. Stefansson was compensated for his efforts by the American Meat Institute.[20] The results were published, and K. Andersen had developed glycosuria during this time, which is normally associated with untreated diabetes. But unlike the pathology of diabetes, in this particular study, glucosuria was present in K. A. for 4 days and coincided only with the giving of a 100 gm of glucose for a tolerance test and with the first 3 days of his pneumonia, where he received fluids and a diet rich in carbohydrate. Once that situation resolved, the glucosuria disappeared.[21] However, Stefansson and Andersen's doctors admitted that their subjects were unable to survive on the significantly higher protein diet that had been observed in the early stages of the dietary experiment. This was due to the doctors insistence on "normal cuts" of meat that were higher in protein and lower in fat as compared to their earlier experiences on the Inuit diet, and the two white explorers could only complete the experiment by eating their own choices of meat which in effect restricted the higher protein and significantly increased the fat intake.[22]

Some years after his first experience with the Eskimos, Dr. Stefansson returned to the Arctic with a colleague, Dr. Karsten Anderson, to carry out research for the American Museum of Natural History. They were supplied with every necessity including a year's supply of 'civilised' food. This they declined, electing instead to live off the land. In the end, the one-year project stretched to four years, during which time the two men ate only the meat they could kill and the fish they could catch in the Canadian Arctic. Neither of the two men suffered any adverse after-effects from their four-year experiment. It was evident to Stefansson, as it had been to Banting, that the body could function perfectly well, remain healthy, vigorous and slender if it used a diet in which as much food was eaten as the body required, only carbohydrate was restricted and the total number of calories was ignored.[23]

In 1928, Stefansson and Anderson entered Bellevue Hospital, New York for a controlled experiment into the effects of an all-meat diet on the body. The committee which was assembled to supervise the experiment was one of the best qualified in medical history, consisting as it did of the leaders of all the branches of science related to the subject. Dr. Eugene F. DuBois, Medical Director of the Russell Sage Foundation (subsequently chief physician at the New York Hospital, and Professor of Physiology at Cornell University Medical College) directed the experiment. The study was designed to find the answers to five questions about which there was some debate. The results of the year-long trial were published in 1930 in the Journal of Biological Chemistry and showed that the answer to all of the questions was: no. There were no deficiency problems; the two men remained perfectly healthy; their bowels remained normal, except that their stools were smaller and did not smell. The absence of starchy and sugary carbohydrates from their diet appeared to have only good effects. Once again, Stefansson discovered that he felt better and was healthier on a diet that restricted carbohydrates. Only when fats were restricted did he suffer any problems. During this experiment his intake had varied between 2,000 and 3,100 calories per day and he derived, by choice, an average of eighty percent of his energy from animal fat and the other twenty percent from protein.[23]

References

- ↑ Natkusiak (ca. 1885–1947), Arctic magazine, Vol. 45, No. 1 (March 1992), pp. 90–92.

- ↑ My Life with the Eskimo, Vilhjalmur Stefansson, Reissued by Kessinger Publishing, 2004. ISBN 1-4179-2395-4

- ↑ "Further Discussion of the 'Blonde Eskimos'",American Anthropologist, vol. 24., 1922, p.229

- ↑ My Life with the Eskimo, 1922, p. 199 (reprinted by Kessinger Publishing, 2004).

- ↑ Newell, Gordon R., ed., H.W. McCurdy Maritime History of the Pacific Northwest, at 242, Superior Publishing, Seattle, Washington, 1966.

- ↑ Stefansson, Vilhjalmur (1922). The Friendly Arctic: The Story of Five Years in Polar Regions. New York: Macmillan.

- ↑ "List of Past Gold Medal Winners" (PDF). Royal Geographical Society. Retrieved 24 August 2015.

- 1 2 Minutes, Explorer's Club, 4 January 1938.

- 1 2 Robert Shulman. Romany Marie: The Queen of Greenwich Village (pp. 93, 110–112). Louisville: Butler Books, 2006. ISBN 1-884532-74-8

- 1 2 Pálsson, Gísli. Travelling Passions: The Hidden Life Of Vilhjalmur Stefansson (pp. 187, 190, 251–252). Lebanon, New Hampshire: University Press of New England, 2005. ISBN 1-58465-510-0

- ↑ "Stefansson Receives Honor By American Polar Society". Christian Science Monitor. February 5, 1940. Retrieved 2011-11-02.

Dr. Vilhjalmur Stefansson, veteran Arctic explorer and author has been unanimously voted in as the third Honorary Member of the American Polar Society by its executive board. He will be presented with an illuminated scroll emblematic of...

- ↑ The History of Science Society "The Society: Past Presidents of the History of Science Society" Archived December 12, 2013, at the Wayback Machine., accessed 4 December 2013

- ↑ "Milestones". Time. December 22, 1941.

Marriage revealed: Explorer Vilhjalmur Stefansson, 62; and Mrs. Evelyn Schwartz Baird, 28, his secretary; in Wellsville, Tennessee

- ↑ Scott catalogue #2222.

- ↑ Srebrnik, Henry. "The Radical 'Second Life' of Vilhjalmur Stefansson," Arctic: Journal of the Arctic Institute of North America 51, 1, 1998: 58–60.

- ↑ Fediuk, Karen. 2000 Vitamin C in the Inuit diet: past and present. MA Thesis, School of Dietetics and Human Nutrition, McGill University 5–7; 95. Retrieved on: December 8, 2007.

- ↑ Peter Heinbecker (1928). "Studies on the Metabolism of Eskimos" (PDF). J. Biol. Chem. 80 (2): 461–475. Retrieved 2014-04-07.

- ↑ A.C. Corcoran; M. Rabinowitch (1937). "A Study of the Blood Lipoids and Blood Protein in Canadian Eastern Arctic Eskimos". Biochem J. 31 (3): 343–348. PMC 1266943

. PMID 16746345.

. PMID 16746345. - ↑ Kang-Jey Ho; Belma Mikkelson; Lena A. Lewis; Sheldon A. Feldman & C. Bruce Taylor (1972). "Alaskan Arctic Eskimo: responses to a customary high fat diet" (PDF). Am J Clin Nutr. 25 (8): 737–745. Retrieved 2014-04-07.

- ↑ Cutlip, Scott (1994). The Unseen Power: Public Relations. London: Routledge. ISBN 0805814655.

- ↑ McClellan WS, Du Bois EF (February 13, 1930). "Clinical Calorimetry: XLV. Prolonged Meat Diets With A Study Of Kidney Function And Ketosis" (PDF). J. Biol. Chem. pp. 651–668. Retrieved 2015-12-16.

- ↑ McClellan WS, Du Bois EF (February 13, 1930). "Clinical Calorimetry: XLV. Prolonged Meat Diets With A Study Of Kidney Function And Ketosis" (PDF). J. Biol. Chem. pp. 651–668. Retrieved 2015-12-16.

“During the first 2 days [Stefansson’s] diet approximated that of the Eskimos, as reported by Krogh and Krogh, except that he took only one-third as much fat. The protein accounted for 45 per cent of his food calories. The intestinal disturbance began on the 3rd day of this diet. During the next 2 days he took much less protein and more fat so that he received about 20 percent of his calories from protein and 80 percent from fat. In these two days his intestinal condition became normal without medication. Thereafter the protein calories did not exceed 25 per cent of the total for more than 1 day at a time.”

- 1 2 Groves, PhD, Barry (2002). "WILLIAM BANTING: The Father of the Low-Carbohydrate Diet". Second Opinions. Retrieved 26 December 2007.

Literature

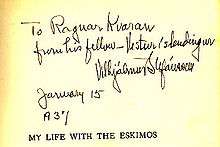

- Stefansson, Vilhjalmur. My Life with the Eskimo; The Macmillan Company, New York, 1912.

- Stefansson, Vilhjalmur. Stefánsson-Anderson Expedition, 1909–12; Anthropological Papers, AMNH, vol. XIV., New York, 1914.

- Stefansson, Vilhjalmur. The Standardization of Error; W. W. Norton & Company, Inc., New York, 1927.

- Stefansson, Vilhjalmur. Unsolved Mysteries of the Arctic; The Macmillan Company, New York, 1938.

- Stefansson, Vilhjalmur. Not by Bread Alone; The Macmillan Company, New York, 1946.

- Stefansson, Vilhjalmur. The Fat of the Land; The Macmillan Company, New York, 1956.

- Stefansson, Vilhjalmur. Discovery – the autobiography of Vilhjalmur Stefansson; McGraw-Hill Book Company, New York, 1964.

- Stefansson, Vilhjalmur. Cancer: Disease of civilization? An anthropological and historical study; Hill and Wang, Inc., New York, 1960.

- Stefansson, Vilhjalmur (ed.). Great Adventures and Explorations; The Dial Press, 1947.

- Diubaldo, Richard. Stefansson and the Canadian Arctic; McGill-Queen's University Press, Montreal, 1978.

- Hunt, William R. Stef: A Biography of Vilhjalmur Stefansson, Canadian Arctic explorer; University of British Columbia Press, Vancouver, 1986. ISBN 0-7748-0247-2

- Jenness, Stuart Edward. The Making of an Explorer: George Hubert Wilkins and the Canadian Arctic Expedition, 1913–1916; McGill-Queen's Press – MQUP, 2004. ISBN 0-7735-2798-2

- Niven, Jennifer. The Ice Master: The Doomed 1913 Voyage of the Karluk, Hyperion Books, 2000.

- Niven, Jennifer. Ada Blackjack: A True Story Of Survival In The Arctic, Hyperion Books, 2003. ISBN 0-7868-8746-X

- Pálsson, Gísli. Writing on Ice: The Ethnographic Notebooks of Vilhjalmur Stefansson; Dartmouth College Press, University Press of New England, Hanover, 2001. ISBN 1-58465-119-9

- Pálsson, Gísli. "The legacy of Vilhjalmur Stefansson", the Stefansson Arctic Institute (and individual authors), 2000.

Further reading

- Henighan, Tom (2009). Vilhjalmur Stefansson: Arctic Traveller. Toronto: Dundurn Press. ISBN 978-1-55002-874-4.

- Stefansson, Vilhjalmur (1957). The fat of the land: Enlarged edition of Not by bread alone. London (Also available online in PDF format): Macmillan.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Vilhjalmur Stefansson. |

- "Adventures in Diet", Harper's Monthly magazine, November 1935

- Biography of Vilhjalmur Stefansson

- Stefansson on enchantedlearning.com

- "Arctic Dreamer" Award-winning documentary on Stefansson's life, includes much archival footage

- The Correspondence files of Vilhjalmur Steffansson in the Rauner Special Collections Library at Dartmouth College

- Stefansson Collection of Arctic Photographs at Dartmouth Digital Library