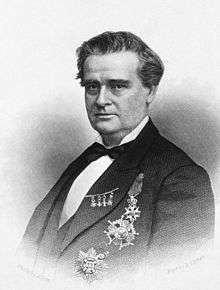

J. Marion Sims

| J. Marion Sims | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born |

January 25, 1813 Lancaster County, South Carolina, U.S. |

| Died |

November 13, 1883 (aged 70) New York City, U.S. |

| Alma mater | Jefferson Medical College |

| Occupation | Surgeon |

| Spouse(s) | Theresa Jones |

| Children | Florence Sims |

| Parent(s) |

John Sims Mahala Mackey |

| Relatives |

John Allan Wyeth (son-in-law) Marion Sims Wyeth (grandson) John Allan Wyeth (grandson) |

James Marion Sims (January 25, 1813 – November 13, 1883) (known as J. Marion Sims) was an American physician and a pioneer in the field of surgery, known as the "father of modern gynecology".[1] His most significant work was to develop a surgical technique for the repair of vesicovaginal fistula, a severe complication of obstructed childbirth.

Sims' use of enslaved African-American women as experimental subjects is considered highly unethical by modern historians and ethicists.[1][2] He is considered "a prime example of progress in the medical profession made at the expense of a vulnerable population."[1] Physician L.L. Wall has attempted to defend Sims on the basis of his conformity to accepted medical practices of the time, the therapeutic nature of his surgery, and the catastrophic nature for women of the condition he was trying to fix.[3]

Early life, education and career

J. Marion Sims (called Marion) was born in Lancasterville, South Carolina, the son of John and Mahala Mackey Sims. Sims's family spent the first twelve years of his life in the Heath Springs area of Lancaster County. He would later write entertainingly of his early school days, but recalled one occasion when he was saved from drowning by fourteen-year-old Arthur Ingram, who lived south of Hanging Rock Creek.

His father, John Sims, was elected sheriff of Lancaster County in 1825 and thereafter took up residence in Lancaster, where the boy, Marion, entered Franklin Academy.

After two years of study at the South Carolina College in Columbia, Sims worked with Dr. Churchill Jones in Lancaster, South Carolina, and took a three-month course at the Medical College of Charleston. He moved to Philadelphia, Pennsylvania and enrolled at the Jefferson Medical College, where he graduated in 1835. He returned to Lancaster to practice but, after the deaths of his first two patients, moved to Alabama.

He returned to Lancaster in 1836 to marry Theresa Jones, the daughter of Dr. Barlett Jones. He met her when he was studying at South Carolina College in Columbia. They moved to Montgomery, Alabama where in 1845 Sims established a private hospital for women.

Medical experimentation on slaves

Repair of vesicovaginal fistula

Women with vesicovaginal fistulas, described as a "catastrophic complication of childbirth," [3] were, in the 19th century, social outcasts as no cure was available. The frequently occurring injuries left the women subject to leaking urine and related medical problems. In Montgomery over a period of 4 years, Sims experimented by surgery on 14 enslaved women with fistulas, most of whom he bought and kept on his property for this purpose. Some were operated on up to 30 times.[1]

He named three enslaved women in his records: Anarcha, Betsy, and Lucy. Each suffered from fistula, and all were subjected to his surgical experimentation.[2] From 1845 to 1849 he experimented on them, operating on Anarcha 30 times. She had "a particularly difficult combination vesicovaginal and rectovaginal fistula", which he struggled to repair.[3]

Although anesthesia had recently become available, Sims did not use any anesthetic during his procedures on Anarcha, Betsy, and Lucy.[2] According to Sims, it was not yet fully accepted into surgical practice.[3] However, ether as anesthesia was available as early as the beginning of the 1840s. Sims did not believe anesthesia was necessary for his procedures, believing that slave women were able to bear great pain due to their 'race' made then more durable thus 'justifying' (to himself and others) the surgeries and experiments. Despite his own memoir stating "Lucy's agony was extreme...she was much prostrated and I thought she was going to die".[4] He did administer opium to the women after their surgery, which was accepted therapeutic practice of the day.[5] Anarcha, Lucy and Betsy are now often referred to as "The Mothers of Modern Gyneocology". [6]

After the extensive experiments and complications, Sims finally perfected his technique. He repaired the fistula successfully in Anarcha. His technique using silver-wire sutures led to successful repair of a fistula, and this was reported in 1852.[1] He then "repaired" several other enslaved women.[7] It was only after his success in early experiments on the enslaved women that Sims attempted the procedure on white women with fistulas; he used anesthesia for their surgeries.

These experiments were the basis for modern vaginal surgery. Sims also devised instruments, including the Sims' vaginal speculum, to aid in examination and surgery. The first vaginal speculum was made out of a pewter spoon. The rectal examination position, in which the patient is on the left side with the right knee flexed against the abdomen and the left knee slightly flexed, is also named after him.

Human Experimentation

Sims has continued to be cited for his groundbreaking work in medical textbooks but, since the late 20th century, historians and ethicists have questioned his practices. His experimental surgeries on enslaved African-American women who could not consent and without anesthesia are considered by many to be unethical; as well as symbolic of the violent oppression of blacks and vulnerable populations in the United States.[1]

Physician L.L. Wall argues that Sims was operating for therapeutic purposes, with the consent of patients as can be determined, and within acceptable medical practices of his time. He believes Sims cannot be judged only in relation to today's standards. He notes that

"modern critics have discounted the enormous suffering experienced by fistula victims, have ignored the controversies that surrounded the introduction of anaesthesia into surgical practice in the middle of the 19th century, and have consistently misrepresented the historical record in their attacks on Sims."[3]

Trismus

Interested in "trismus nascentium", Sims began experimenting on the infants born to slave women. Although it is now known to be the result of unsanitary practices and nutritional deficiencies, Sims attributed trismus to 'intellectual flaws and indecencies of blacks with the skull formation at birth.' To test this, Sims used a shoemaker's awl to pry the skull bones of babies into alignment; these experiments had a 100% fatality rate. He then blamed these fatalities on "the sloth and ignorance of their mothers and the black midwives who attended them".[8][9]

New York and Europe

Sims moved to New York in 1853 because of his health and determined to focus on diseases of women. In 1855 he founded the Woman's Hospital, the first hospital for women in America. Here he performed operations on indigent women, often in a theatre so that medical students and other doctors could view it, as was considered fundamental to medical education at the time;[10] notably, the patients remained in the hospital "indefinitely" and underwent repeated procedures.[10]

In 1862, during the American Civil War, Sims moved to Europe, where he worked primarily in London and Paris. From 1863 to 1866, he served as surgeon to Empress Eugénie. His private practice became extremely expensive and only available to the wealthy. Sims also became known for the Battey surgery which contributed to his "honorable reputation". The Battey surgery was the removal of both ovaries, which became a "popular" "treatment" insanity, epilepsy, hysteria, and other disorders of the nerves that were thought to be from the female reproductive system (Terri Kapsalis).[11] Honors and medals were heaped upon him for his successful operations in many countries. The necessity of many of these surgeries have since been called into question. Several of his patients had surgery for what were considered gynecological issues: such as clitoridectomies, believed to control hysteria or 'improper' behavior related to sexuality. These were done at the requests of their husbands/fathers, who were permitted under the law to commit the women to surgery involuntarily.[7]

Under the patronage of Napoleon III, Sims organized the American-Anglo Ambulance Corps, which treated wounded soldiers from both sides at the battle of Sedan.[7]

In 1871, Sims returned to New York. After quarreling with the board of the Woman's Hospital over the admission of cancer patients (which he favored and which the board opposed because of the mistaken belief that cancer was contagious) he became instrumental in establishing America's first cancer institute, New York Cancer Hospital.

From 1876–77, Sims served as president of the American Medical Association. He was halfway through writing his autobiography and planning a return visit to Europe when he died of a heart attack on November 13, 1883 in New York. He is buried at Green-Wood Cemetery in Brooklyn, New York.[12]

Relatives

His grandson was architect Marion Sims Wyeth.

Legacy and honors

- A bronze statue by Ferdinand Freiherr von Miller (the younger), depicting Sims in surgical wear,[13] where it is located on the peripheral wall at Fifth Avenue and 103rd Street, opposite the New York Academy of Medicine. This is the first statue in the United States to depict a physician.[7]

- Other memorials were installed on the grounds of his alma mater, Jefferson Medical College, and in both the South Carolina State Capitol in Columbia and Alabama's capitol in Montgomery.[1]

- The historical marker of his birthplace honors him for “his service to suffering women. Empress and slave alike."[1]

Contributions

- Vaginal surgery: fistula repair.

- Instrumentation: Sims' speculum; Sims' sigmoid catheter.

- Exam and surgical positioning: Sims' position.

- Fertility treatment: Insemination and postcoital test.

- Cancer care: Sims argued for the admission of cancer patients to the Woman's Hospital, at a time when people opposed him, as they feared that cancer was contagious.

- Abdominal surgery: Sims advocated that in the case of an abdominal bullet wound, a laparotomy was needed to stop bleeding, repair the damage and drain the wound. His opinion was sought when President James Garfield was shot; he responded by telegram from Paris. Sims' recommendations later gained acceptance.[7]

- Gallbladder surgery: In 1878, Sims drained a distended gallbladder and removed its stones. He published the case believing it was the first of its kind; however, a similar case had already been reported in Indianapolis in 1867.[7]

Death

Sims died in New York City in 1883 at the age of 70.

See also

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Sarah Spettel and Mark Donald White, "The Portrayal of J. Marion Sims' Controversial Surgical Legacy", THE JOURNAL OF UROLOGY, Vol. 185, 2424-2427, June 2011, accessed 4 November 2013

- 1 2 3 Lerner, Barbara (October 28, 2003). "Scholars Argue Over Legacy of Surgeon Who Was Lionized, Then Vilified". New York Times.

- 1 2 3 4 5 L. L. Wall, "The medical ethics of Dr J Marion Sims: a fresh look at the historical record", J Med Ethics, 2006 June; 32(6): 346–350, accessed 4 November 2013

- ↑ https://books.google.com/books?id=apGhwRt6A7QC&pg=PA63&hl=en#v=onepage&q&f=false

- ↑ Wall LL, "Did J. Marion Sims Deliberately Addict His First Fistula Patients to Opium?", Journal of the History of Medicine and Allied Sciences, Vol 62:3, 336–356, Oxford University Press, at National Library of Medicine, NIH, accessed 4 November 2013

- ↑ http://www.npr.org/2016/02/16/466942135/remembering-anarcha-lucy-and-betsey-the-mothers-of-modern-gynecology

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 H M Shingleton (March–April 2009). "The Lesser Known Dr. Sims". ACOG Clinical Review. 14 (2): 13–16.

- ↑ Medical Apartheid: The Dark History of Medical Experimentation on Black Americans from Colonial Times to the Present, (page 62-63) by Harriet A. Washington; published 2008 by Knopf Doubleday (via Google Books)

- ↑ When Doctors Kill: Who, Why, and How (p. 88), by Joshua A. Perper and Stephen J. Cina; published 2010 by Springer Science & Business Media

- 1 2 Public Privates: Performing Gynecology from Both Ends of the Speculum, page 46; by Terri Kapsalis; published 1997 by Duke University Press

- ↑ Public Privates: Performing Gynecology from Both Ends of the Speculum

- ↑ Dr. James Marion Sims, American Physician at Find a Grave

- ↑ The bronze standing figure is signed "[F. v]on Miller fec. München 1892"; was erected and dedicated in Reservoir Square, now Bryant Park, in 1894. It was moved to Central Park in 1934 (Text of historical sign).

Further reading

- Gamble, Vanessa. "Under the Shadow of Tuskegee: African Americans and Health Care". American Journal of Public Health, November 1997, page 1773.

- Harris, Seale. Woman’s Surgeon (1950), short biography

- Sims, J. Marion. The Story of My Life. Appleton, New York, 1889, pages 236–237, online text at Internet Archive.

- Sims, James Marion (1866). Clinical notes on uterine surgery. Robert Hardwicke. Retrieved 16 July 2015.

- Speert H. Obstetrics and Gynecologic Milestones. The MacMillan Co., New York, 1958, pages 442–54.

- Spencer, Thomas. "UAB shelves divisive portrait of medical titans: Gynecologist's practices at heart of debate," Birmingham News, January 21, 2006.

- Washington, Harriet A. "Medical Apartheid: The Dark History of Medical Experimentation on Black Americans from Colonial Times to the Present" Medical Apartheid at the Wayback Machine (archived July 14, 2011)

External links

- "J. Marion Sims", Encyclopedia of Alabama

-

"Sims, James Marion". Appletons' Cyclopædia of American Biography. 1900.

"Sims, James Marion". Appletons' Cyclopædia of American Biography. 1900. - J. Marion Sims Letters, South Carolina Digital Library