JCVD (film)

| JCVD | |

|---|---|

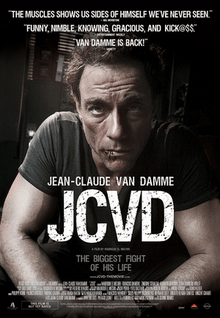

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Mabrouk El Mechri |

| Produced by |

Sidonie Dumas Fiszman Marc Patrick Quinet Jani Thiltges Jean-Claude Van Damme Arlette Zylberberg |

| Written by |

Frédéric Bénudis Mabrouk El Mechri Christophe Turpin |

| Starring |

Jean-Claude Van Damme François Damiens Zinedine Soualem |

| Music by | Gast Waltzing |

| Cinematography | Pierre-Yves Bastard |

| Edited by | Kako Kelber |

Production company | |

| Distributed by |

Gaumont Distribution (France) Peace Arch Entertainment (USA/Canada) |

Release dates |

|

Running time | 96 min |

| Country |

Belgium France Luxembourg |

| Language |

French English |

| Box office | $2,342,211[1] |

JCVD[2] is a 2008 Belgian crime drama film directed by French Tunisian film director Mabrouk El Mechri, and starring Jean-Claude Van Damme as a semi-fictionalized version of himself, a down and out action star whose family and career are crumbling around him as he is caught in the middle of a post office heist in his hometown of Brussels, Belgium.

The film was screened on June 4, 2008 in Belgium and France, at the 2008 Toronto International Film Festival (Midnight Madness), and at the Adelaide Film Festival on 20 February 2009. It was distributed by Peace Arch Entertainment from Toronto and opened in New York and select cities on 7 November 2008.

Plot

The film establishes Jean-Claude Van Damme playing himself as an out-of-luck actor. He is out of money; his agent cannot find him a decent production; and the judge in a custody battle is inclined to give custody of his daughter over to his ex-wife. His own daughter rejects him as a father, much to his chagrin. He returns to his childhood home of Schaarbeek in the Brussels capital region, Belgium, where he is still considered a national icon.

After posing for pictures with clerks outside a video store, Van Damme goes into the post office across the street. A shot is fired inside the post office, and a police officer responds but is waved off by Van Damme at the window, which is then blocked. He calls for backup.

The narrative then shifts to Van Damme's point of view. He goes into the post office to receive a badly needed wire transfer but finds that the bank is being robbed. He is taken hostage along with the others. The police mistakenly identify Van Damme as the robber when he is forced to move a cabinet to block the window. Van Damme finds himself acting as a hero to protect the hostages by engaging with the robbers about his career, as well as both a negotiator and presumed perpetrator. While speaking by phone as the ringleader of the robbers, Van Damme even goes so far as to demand $465,000 for the law firm handling his custody case. It is not clear if Van Damme demands the $465, 000 out of self-interest or out of a desire to appear as a genuine bank-robber to the police as he insists to the thieves or perhaps both.

The narrative continues to shift to show Van Damme's troubles getting roles and money, and the media circus that develops around the post office and video store, which the police use as a base of operations.

In a notable scene, Van Damme and the camera are lifted above the set, and he performs a six-minute single-take monologue, where he breaks the fourth wall addressing the audience directly with an emotional (but characteristically cryptic) monologue about his career, his multiple marriages, and his drug abuse.

Van Damme then persuades one of the bank robbers to release the hostages. After this happens, a scuffle ensues and in the resulting conflict, the head robber is shot. The police, after hearing a gunshot, storm the building. The police shoot another one of the thieves, and Van Damme is held at gunpoint by the final one. Van Damme briefly imagines a scenario in which he takes the robber out by elbowing him and kicking him in the face and everyone including the police and crowd cheering for him, but in reality, he just elbows him in the stomach, and the police take him into custody.

Van Damme is arrested for extortion over the $465,000 and sentenced to 1 year in prison. The final scenes show him teaching karate to other inmates, then being visited by his mother and daughter.

Cast

- Jean-Claude Van Damme as himself

- François Damiens as Bruges

- Zinedine Soualem as The Man with the Cap

- Karim Belkhadra as The Vigil

- Jean-François Wolff as The Thirty

- Anne Paulicevich as The Teller

- Saskia Flanders as Van Damme's daughter

- Dean Gregory as the Director of Tobey Wood

- Kim Hermans as the Prisoner in kickboxing outfit

- Steve Preston as Van Damme's Assistant

- Paul Rockenbrod as Tobey Wood

- Alan Rossett as Bernstein

- Jesse Joe Walsh as Jeff

Production

The concept for the film originated from a producer who had an agreement with Van Damme to play himself in a movie. The producer, knowing El Mechri was a Van Damme fan, asked him to review the original screenplay. The screenwriters had perceived Van Damme as merely a clown, but El Mechri felt that there was more to Van Damme than just what people knew from his big screen action-hero persona.

El Mechri, who was influenced by Jean-Luc Godard,[3] offered to write a draft, and the producer asked if he would direct it as well. El Mechri agreed on the condition he could meet Van Damme first before starting the draft, so he would not waste six months on something that Van Damme might veto. El Mechri and Van Damme had dinner, where the idea of the bank heist and not knowing what has happened inside was pitched. Van Damme was thrilled with the concept. After watching El Mechri's film, Virgil, he immediately went to work with the French director.

El Mechri stated that about 70% of the film was scripted, and the other 30% was improvised from the actors. Most of the ad-libs came from Van Damme.

During Van Damme's six-minute, one-take monologue, he references past drug problems. In real life, Van Damme had troubles with cocaine during 1995, entering a month-long rehab program in 1996 but leaving after just one week.

The Gaumont title sequence was altered for this film. The normal sequence has a silhouetted boy pulling a daisy from the ground, which floats to space to become the company logo. In this film, the boy is confronted by a silhouetted Van Damme, who attempts to take the daisy from him. When the boy resists, Van Damme does a roundhouse kick on him and kicks the daisy upwards, where it becomes the company logo.

Reception

Reviews for JCVD have been positive. As of November 11, 2011, Rotten Tomatoes has the film rated at 83% on the Tomatometer, based on 100 reviews. To date, this is one of only four Van Damme films to be listed as Certified Fresh by the aggregate website, along with The Expendables 2, Enemies Closer and Kung Fu Panda 2.[4] Peter Bradshaw reviewed the film for The Guardian and called the monologue "a Godardian coup de cinéma", describing the film as "inter-textual and self-referential".[5]

Richard Corliss of Time magazine named Van Damme's performance in the film the second best of the year (after Heath Ledger's The Joker in The Dark Knight),[6] having previously stated that Van Damme "deserves not a black belt, but an Oscar".[7] Roger Ebert gave the film 2.5 stars, noting that the movie "almost endearingly savages" Van Damme, who "says worse things about himself than critics would dream of saying, and the effect is shockingly truthful".[8]

References

- ↑ "JCVD (2008)". Box Office Mojo. IMDb.com. Retrieved 12 June 2011.

- ↑ The title is the initials of the main character, Jean-Claude Van Damme.

- ↑ Burr, Ty (6 September 2008). "Toronto, Day 2: Spike, Nick, Pitt, Zac, and Jean-Claude". Boston Globe. The New York Times Company. Retrieved 1 October 2009.

- ↑ "JCVD (2008)". Rotten Tomatoes. IGN Entertainment. Retrieved 1 October 2009.

- ↑ Bradshaw, Peter (30 January 2009). "Film review: JCVD". The Guardian. London: Guardian News and Media. Retrieved 1 October 2009.

- ↑ Corliss, Richard (3 November 2008). "The Top 10 Everything of 2008: Top 10 Movie Performances". Time. Time Warner. Retrieved 1 October 2009.

- ↑ Corliss, Richard; Grossman, Lev; Ponewozik, James; Zoglin, Richard (13 November 2008). "Short List". Time. Time Warner. Retrieved 1 October 2009.

- ↑ Roger Ebert (12 November 2008). "JCVD (R)". Chicago Sun-Times. Retrieved 10 August 2010.

External links

- JCVD at AllMovie

- JCVD at the Internet Movie Database

- JCVD at Rotten Tomatoes

- JCVD at Metacritic