Jami' al-tawarikh

The Jāmiʿ al-tawārīkh, (Arabic: جامع التواريخ Compendium of Chronicles, Mongolian: Судрын чуулган, Persian: جامعالتواریخ ) is a work of literature and history, produced in the Mongol Ilkhanate in Persia.[1] Written by Rashid-al-Din Hamadani (1247–1318) at the start of the 14th century, the breadth of coverage of the work has caused it to be called "the first world history".[2] It was in three volumes. The surviving portions total approximately 400 pages, with versions in Persian and Arabic. The work describes cultures and major events in world history from China to Europe; in addition, it covers Mongol history, as a way of establishing their cultural legacy.[3]

The lavish illustrations and calligraphy required the efforts of hundreds of scribes and artists, with the intent that two new copies (one in Persian, and one in Arabic) would be created each year and distributed to schools and cities around the Ilkhanate, in the Middle East, Central Asia, Anatolia, and the Indian subcontinent. Approximately 20 illustrated copies were made of the work during Rashid al-Din's lifetime, but only a few portions remain, and the complete text has not survived. The oldest known copy is an Arabic version, of which half has been lost, but one set of pages is currently in the Khalili Collection, comprising 59 folios from the second volume of the work. Another set of pages, with 151 folios from the same volume, is owned by the Edinburgh University Library. Two Persian copies from the first generation of manuscripts survive in the Topkapı Palace Library in Istanbul. The early illustrated manuscripts together represent "one of the most important surviving examples of Ilkhanid art in any medium",[4] and are the largest surviving body of early examples of the Persian miniature.

The author

Rashid-al-Din Hamadani was born in 1247 at Hamadan, Iran into a Jewish family. The son of an apothecary, he studied medicine and joined the court of the Ilkhan emperor, Abaqa Khan, in that capacity. He converted to Islam around the age of thirty. He rapidly gained political importance, and in 1304 became the vizier of emperor and Muslim convert Ghazan. He retained his position until 1316, experiencing three successive reigns, but, convicted of having poisoned the second of these three Khans, Öljaitü, he was executed on July 13, 1318.

Hamdani was responsible for setting up a stable social and economic system in Iran after the destruction of the Mongol invasions, and was an important artistic and architectural patron. He expanded the university at Rab'-e Rashidi, which attracted scholars and students from Egypt and Syria to China, and which published his many works.[5] He was also a prolific author, though few of his works have survived: only a few theological writings and a correspondence which is probably apocryphal are known today in addition to the Jāmiʿ al-tawārīkh. His immense wealth made it said of him that he was the best paid author in Iran.

The work

The Jāmiʿ al-tawārīkh was one of the grandest projects of the Ilkhanate period,[6] "not just a lavishly illustrated book, but a vehicle to justify Mongol hegemony over Iran".[7] The text was initially commissioned by Il-Khan Ghazan, who was anxious for the Mongols to retain a memory of their nomadic roots, now that they had become settled and adopted Persian customs. Initially, the work was intended only to set out the history of the Mongols and their predecessors on the steppes, and took the name Taʾrīkh-ī Ghazānī, which makes up one part of the Jāmiʿ al-tawārīkh. To compile the History, Rashid al-Din set up an entire precinct at the university of Rab'-e Rashidi in the capital of Tabriz. It contained multiple buildings, including a mosque, hospital, library, and classrooms, employing over 300 workers.[6]

After the death of Ghazan in 1304, his successor Öljaitü asked Rashid al-Din to extend the work, and write a history of the whole of the known world. This text was finally completed in sometime between 1306 and 1311.

After Rashid al-Din's execution in 1318, the Rab-i-Rashidi precinct was plundered, but the in-process copy that was being created at the time survived, probably somewhere in the city of Tabriz, possibly in the library of Rashid's son, Ghiyath al-Din. Later, Rashid's son became Vizier, in his own right, and expanded the restored university precinct of his father. Several of the Jāmiʿ's compositions were used as models for the later seminal illustrated version of the Shahnameh known as the Demotte Shahnameh.[8]

In the 15th century, the Arabic copy was in Herat, perhaps claimed after a victory by the Timurid dynasty. It then passed to the court of the Mughal Empire in India, where it was in the possession of the emperor Akbar (r. 1556–1605). There is then a record of it passing through the hands of later Mughal emperors for the next few centuries. It was probably divided into two parts in the mid-1700s, though both sections remained in India until the 19th century, when they were acquired by the British. The portion now in the Edinburgh library was presented as a gift to Ali-I Ahmad Araf Sahib on October 8, 1761, and in 1800 was in the library of the Indian prince Farzada Kuli. This fragment was acquired by Colonel John Baillie of Leys of the East India Company, and then in 1876 passed to the Edinburgh University Library.[8] The other portion was acquired by John Staples Harriott of the East India Company sometime prior to 1813. At some point during the next two decades it was brought to England, probably when Harriott came home on furlough, when the manuscript entered the collection of Major General Thomas Gordon. He then bequeathed it to the Royal Asiatic Society in 1841. In 1948, it was loaned to the British Museum and Library, and in 1980 was auctioned at Sotheby's, where it was purchased by the Rashidiyyah Foundation in Geneva for £850,000, the highest price ever paid for a medieval manuscript.[9] The Khalili Collection acquired it in 1990.

Sources

To write the Jāmiʿ al-tawārīkh, Rashid al-din based his work on many written and oral sources, some of which can be identified:

- From Iran, it is very similar to work by Ata-Malik Juvayni, a Persian historian who wrote an account of the Mongol Empire entitled Taʾrīkh-ī jahān-gushāy "History of the World-Conqueror". Also from Iran, the Shahnameh is drawn upon.[10]

- For Europe, the Chronicle of the Popes and the Emperors of Martin of Opava

- For the Mongols, it seems that he had access to the Altan Debter, through the ambassador of the Great Khan to the court of the Il-Khanate.

- For China, the author knew the translation of four Chinese manuscripts: three on medicine and one on administration. Furthermore, it is known that he enjoyed calligraphy, painting and Chinese music. The links with this world were made all the easier because Mongols also ruled the Chinese empire.

Contents

The Jāmiʿ al-tawārīkh consists of four main sections of different lengths:

1. The Taʾrīkh-ī Ghazānī, the most extensive part, which includes:

- The Mongol and Turkish tribes: their history, genealogies and legends

- The history of the Mongols from Genghis Khan up to the death of Mahmud Ghazan

2. The second part includes :

- The history of the reign of Öljaitü up to 1310 (no known copy)

- The history of the non-Mongol peoples of Eurasia (a universal history from the time of Creation, following the organization of work of the Abbasid historian al-Tabari in his History of the Prophets and Kings, often referred to as at-Tabari's HIstory, and to the historic Muslim history of Qazi Beiza'i in the Neẓām al-tawārīkh:

- Adam and the patriarchs

- the kings of the pre-Islamic Iran

- Muhammad and the Caliphs (Rashidun, Umayyad, Abbasid and Fatimid Caliphates)

- the Islamic dynasties of Persia (Ghaznavids, the shahs of Khwarezm, the Isma'ili-ruled Alamut)

- the Turkic peoples,

- the History of China

- Jewish history,

- Frangistan (ie., Europe, primarily the Papal States and Holy Roman Empire)

- the Indians.

3. The Shu'ab-i panjganah ("Five genealogies, of the Arabs, Jews, Mongols, Franks, and Chinese"). This text exists in two copies of the manuscript in the library of the Topkapı Palace in Istanbul (ms 2937), but has only been published on microfilm.

4. The Suwar al-akalim, a geographical compendium. Unfortunately, it has not survived in any known manuscript.

Illustrations

Recent scholarship has noted that, although surviving early examples are now uncommon, human figurative art was a continuous tradition in the Muslim world in secular contexts (such as literature, science, and history); as early as the 9th century, such art flourished during the Abbasid Caliphate (c. 749-1258, across Spain, North Africa, Egypt, Syria, Turkey, Mesopotamia, and Persia).[11] Although much of the illustration for the various Tawarikh copies was probably done at the Rab-al Rashidi university complex, a contemporary written account mentions that they were also done elsewhere in Mongol empire.[12]

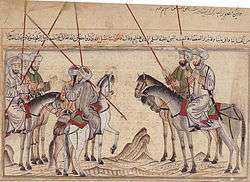

The scene now in the Kahlili collection illustrating the Battle of Badr used a collection of stock figures, and scholars are in disagreement as to who is represented. One descriptor says it shows Muhammad with Hamza ibn Abdul-Muttalib and Ali before sending them to battle. Another says Muhammad is on the right, but Hamza and Ali on the left, or perhaps the center. Another description says it is Muhammad exhorting his family to fight, and that he may be one of the central figures, but it is not clear which one.[14]

Questions about the Jāmiʿ al-tawārīkh

There is little reason to doubt Rashid al-Din’s editorial authorship but the work is generally considered a collective effort. It may also be possible that it was compiled by a group of international scholars under his leadership. Yet, a number of questions remain about the writing of the Jāmiʿ al-tawārīkh. Several others, such as Abu’l Qasim al-Kashani, claimed to have written the universal history. Rashid al-Din was of course a very busy man, with his public life, and would have employed assistants to handle the materials assembled and to write the first draft: Abu'l Qasim may have been one of them. Furthermore, not all of the work is original: for instance, the section on the period following the death of Genghis Khan in particular is directly borrowed from Juvayni. Other questions concern the objectivity of the author and his point of view: it is after all an official history, concerning events with which Rashid al-Din in his political capacity was often involved at first hand (for the history of the Ilkhanate in particular). Nonetheless, the work "is characterized by a matter-of-fact tone and a refreshing absence of sycophantic flattery." [2]

Contemporary manuscripts of the Jāmiʿ al-tawārīkh

The Jāmiʿ al-tawārīkh was the center of an industry for a time, no doubt in part due to the political importance of its author. The workshop was ordered to produce one manuscript each in Arabic and Persian every year, which were to be distributed to different cities.[15] Although approximately 20 of the first generation of manuscripts were produced, very few survive, which are described below. Other later copies were made from the first set, with some illustrations and history added to match current events.[16]

Arabic manuscripts

The earliest known copy is in Arabic, dated to the early 1300s. Only portions of it have survived,[17] divided into two parts between the University of Edinburgh (151 folios) and the Khalili Collection (59 folios), although some researchers argue for these being from two different copies. Both sections come from the second volume, with the pages interwoven. The Edinburgh part covers some of the earlier history up through a section about the Prophet Muhammad, and then this story is continued in the Khalili portion, with further narratives weaving back and forth between the two collections, ending with the final section also being in the Edinburgh collection.

Edinburgh folios

The Edinburgh part has a page size of 41.5 × 34.2 cm, with a written area of 37 × 25 cm, and contains 35 lines per page written in Naskhi calligraphy. There are some omissions: folios 1, 2, 70 to 170, and the end; and it is dated to 1306-1307, in a later inscription, which is nonetheless accepted. The text comprises four parts: the history of Persia and pre-Islamic Arabia, the story of the Prophet and Caliphs, the history of the Ghaznavids, Seljuks and Atabeys, and the history of the sultans of Khwarezm. This part of the manuscript was discovered in the 1800s by Duncan Forbes, who found it among the papers of Colonel John Baillie, so this section is sometimes referred to as "Baillie's collection".

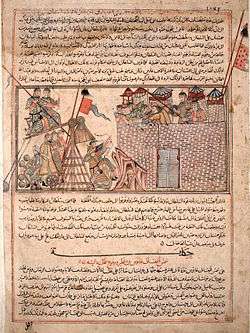

Seventy rectangular miniatures adorn the manuscript, which reflect the cosmopolitan nature of Tabriz at the time of its production. In this capital, a crossroads of trade routes and influences, and a place of great religious tolerance, Christian, Chinese, Buddhist and other models of painting all arrived to feed the inspiration of the artists.

The miniatures have an unusual horizontal format and only take up about a third of the written area; this may reflect the influence of Chinese scrolls. Some parts of the surviving text are heavily illustrated and other parts not at all, apparently reflecting the importance accorded to them. The miniatures are ink drawings with watercolour washes added, a technique also used in China; although they are generally in good condition, there was considerable use of metallic silver for highlights, which has now oxidized to black. Borrowings from Christian art can also be seen; for example the Birth of Muhammad adapts the standard Byzantine composition for the Nativity of Jesus, but instead of the Biblical Magi approaching at the left there is a file of three women.[18] The section includes the earliest extended cycle of illustrations of the life of Muhammad. Like other early Ilkhanid miniatures, these differ from the relatively few surviving earlier Islamic book illustrations in having coherent landscape backgrounds in the many scenes set outside, rather than isolated elements of plants or rocks. Architectural settings are sometimes given a sense of depth by different layers being shown and the use of a three-quarters view.[19]

Rice distinguished four major painters and two assistants:

- The Painter of Iram: the most influenced by China (reflected in Chinese elements, such as trees, interest in the landscape, interest in contemplative characters). The work is characterized by open drawing, minimal modelling, linear drapery, extensive details, stripped and balanced compositions, delicate and pale colours, and a rare use of silver. He painted mostly the early miniatures, and may have been assisted by the Master of Tahmura.

- The Painter of Lohrasp: characterized by a variety of subjects, including many throne scenes, a variable and eclectic style, quite severe and angular drapery, a verity of movements, stripped and empty backgrounds. His absence of interest in landscape painting shows a lack of Chinese influences, which is compensated for by inspiration from Arab, Syrian and Mesopotamian painting. His work is of variable quality, and uses silver systematically. His assistant: the Master of Scenes from the Life of the Prophet.

- The Master of the Battle Scenes: a somewhat careless painter, as becomes evident when the number of arms does not match the number of characters, or a leg is missing among the horses. He is notable for a complete lack of focus and horror, and for strong symmetry, his compositions usually comprising two parties face to face composed of a leader and two or three followers. Decoration is limited to grass, indicated in small vegetative clumps, except during sieges and attacks on the city.

- The Master of Alp Arslan appears briefly, at the end of the manuscript. His style is crude and unbalanced, his characters often badly proportioned.

Just as distinguishable are different racial and ethnic types, made manifest not just in the physical attributes of the characters, but also their clothes and their hats. One can thus distinguish a remarkably well observed group of Abyssinians, Western-style figures based on Syrian Christian manuscripts, Chinese, Mongols, Arabs, and so on.

The Edinburgh folios were displayed at an exhibition at the University of Edinburgh Main Library in summer 2014[20]

Khalili folios

The portion in the Khalili Collection, where it is referred to as MSS727, contains 59 folios, 35 of them illustrated. Until sold in 1980 it was owned by the Royal Asiatic Society in London. It is a different section of the History than that of the Edinburgh version, possibly from a different copy. Each page measures 43.5 by 30 centimetres (17.1 by 11.8 in) (slightly different dimensions to the Edinburgh portion due to different models copied). According to Blair's description of the collection, "Two major sections were lost after division: thirty-five folios (73-107) covering the life of Muhammad up to the caliphate of Hisham, and thirty folios (291-48) going from the end of the Khwarazmshahs to the middle of the section on China. The latter may have been lost accidentally, but the former block may have been jettisoned deliberately because it had no illustrations. The folios about the life of the Prophet were further jumbled, and four were lost. The final three folios (301-303) covering the end of the section on the Jews were also lost, perhaps accidentally, but judging from the comparable section in MS.H 1653, they had no illustrations and may also have been discarded."[21]

The manuscript was brought to Western attention by William Morley, who discovered it in 1841 while he was cataloguing the collection of the Royal Asiatic Society in London. For some time this collection was displayed in the King's Library of the British Museum. It includes twenty illustrations, plus fifteen pages with portraits of the emperors of China. The text covers the history of Islam, the end of China's history, the history of India, and a fragment from the history of the Jews. The work of the Painter of Luhrasp and Master of Alp Arslan is again evident. Some differences in style can be observed, but these can be attributed to the difference in date. A new painter appears for the portraits of Chinese leaders, which uses special techniques that seem to mimic those of Yuan mural painters (according to S. Blair): an attention to line and wash, and the use of black and bright red. This artist seems to be very familiar with China.[22] The folios are dated 1314, and it was transcribed and illustrated in Tabriz under the supervision of Rashid al-Din.

Persian manuscripts

There are two early 14th century copies in Persian in the Topkapi Palace Library, Istanbul.

- MS H 1653, made in 1314, which includes later additions on the Timurid era for Sultan Shah Rukh. The full collection, known as the Majmu'ah, contains Bal'ami's version of Muhammad ibn Jarir al-Tabari's chronicle, the Jāmiʿ al-tawārīkh, and Nizam al-Din Shami's biography of Timur. The portions of the Jāmiʿ cover most of the history of the Muhammad and the Caliphate, plus the post-caliphate dynasties of the Ghaznavids, Saljuqs, Khwarazmshahs and Is'mailis, and the Turks. It contains 68 paintings in the Ilkhanid style.

- MS H 1654, made in 1317, which includes 118 illustrations, including 21 pages of portraits of Chinese emperors. It was copied for Rashid al-Din, and like H 1653 was later owned by Shahrukh.[23]

Later versions and manuscripts

Interest in the work continued after the Ilkhans were replaced as Persia's ruling dynasty by the Timurids. Timur's youngest son, Shahrukh, who ruled the eastern portion of the empire from 1405–47, owned incomplete copies of the Jāmiʿ al-tawārīkh and commissioned his court historian Hafiz-i Abru to complete it. The earliest dated manuscript made for Shahrukh includes the original text and additions by Hafiz-i Abru, along with other histories, and is dated 1415-16 (Topkapi Palace Library, MS B 282). The Topkapi MS H 1653, discussed above, combines an incomplete Ilkhanid Jāmiʿ with Timurid additions, which are dated 1425. Another Jāmiʿ is in Paris (BnF, Supplément persan 1113), dated to about 1430, with 113 miniatures. Most of the miniatures for these volumes copy the horizontal format and other features of the Ilkhanid manuscripts, while retaining other features of Timurid style in costume, colouring and composition, using what is sometimes known as the "Historical style".[24]

See also

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Jami al-Tawarikh. |

Notes

- ↑ Inal. p. 163.

- 1 2 Melville, Charles. "JĀMEʿ AL-TAWĀRIḴ". Encyclopædia Iranica. Columbia University. Retrieved 2 February 2012.

- ↑ Carey. p. 158

- ↑ Compendium of Chronicles, p. 9

- ↑ Sadigh, Soudabeh. "Ilkhanid Structures Discovered in Tabriz". CHN. Retrieved 23 January 2012.

- 1 2 Carey, Moya (2010). The Illustrated Encyclopedia of Islamic Art and Architecture. Lorenz Books. p. 158. ISBN 978-0-7548-2087-1.

- ↑ Blair and Bloom, 3

- 1 2 Blair. pp. 31–32.

- ↑ Blair. p. 36

- ↑ Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge

- ↑ J. Bloom & S. Blair (2009). Grove Encyclopedia of Islamic Art Vol. II. New York: Oxford University Press, Inc. pp. 192 and 207. ISBN 978-0-19-530991-1.

- ↑ Bloom & Blair, Grove Enlycl., Vol. II p. 214

- ↑ al-Din, Rashid (1305–14). "Khalili Collection, MSS. 727, folio 66a". Jāmiʿ al-tawārīkh.

- ↑ Blair. p. 70

- ↑ Carey, pp. 158–159

- ↑ Canby, 31

- ↑ "Folios from the Jami' al-tavarikh". Timeline of Art History. Metropolitan Museum of Art. Retrieved January 15, 2012.

Today only two early-fourteenth-century Persian copies of the Compendium and part of one Arabic copy survive.

- ↑ Blair and Bloom, 28; Canby, 31

- ↑ Min Yong Cho, 12-18

- ↑ Smith, Emma; Skeldon, Steven. "The World History of Rashid al-Din, 1314. A Masterpiece of Islamic Painting". http://libraryblogs.is.ed.ac.uk. Retrieved 16 February 2015. External link in

|website=(help) - ↑ Blair. p. 34.

- ↑ Blair, Sheila (1995). A compendium of chronicles: Rashid al-Din's illustrated history of the world. Nour Foundation in association with Azimuth Editions and Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-727627-3.

- ↑ Blair. pp. 27–28, and note 35.

- ↑ Blair and Bloom, 58 and notes

References

- "Rashid al-Din Tabib", in Encyclopedia of Islam, Brill, 1960 (2nd edition)

- Allen, Terry, Byzantine Sources for the Jāmiʿ al-Tawārīkh of Rashīd Al-Dīn, 1985, Ars Orientalis, Vol. 15, pp. 121–136, JSTOR 4543049

- S. Blair, A compendium of chronicles : Rashid al-Din’s illustrated history of the world, 1995, 2006 ISBN 1-874780-65-X (contains a complete set of the folios from Khalili collection, with discussion of the work as a whole)

- S. Blair and J. Bloom, The Art and Architecture of Islam 1250–1800, Yale University Press, 1994 ISBN 0-300-05888-8

- Canby, Sheila R., Persian Painting, 1993, British Museum Press, ISBN 978-0-7141-1459-0

- O. Grabar, Mostly Miniatures: An Introduction to Persian Painting, Princeton University Press, 2000 ISBN 0-691-04941-6

- B. Gray, Persian painting, Macmillan, 1978 ISBN 0-333-22374-8

- B. Gray, The 'World history' of Rashid al-Din: A study of the Royal Asiatic Society manuscript, Faber, 1978 ISBN 0-571-10918-7

- Inal, Guner (1963). "Some miniatures of the 'Jami' al-Tavrikh' in Istanbul, Topkapi Museum, Hazine Library No. 1654". Ars Orientalis. Freer Gallery of Art, The Smithsonian Institution and Department of the History of Art, University of Michigan. 5: 163–175. JSTOR 4629187.

- Min Yong Cho, How land came into the picture: Rendering history in the fourteenth-century "Jami al-Tawarikh" (Dissertation), 2008, ProQuest, ISBN 0-549-98080-6, ISBN 978-0-549-98080-3, fully online

- D. T. Rice, Basil Gray (ed.), The illustrations to the “World History” of Rashid al-Din, Edinburgh University Press, 1976 ISBN 0-85224-271-9

- A.Z.V. Togan, The composition of the history of the Mongols by Rashid al-din, Central Asiatic Journal, 1962, pp 60 – 72.

External links

- Online text: Elliot, H. M. (Henry Miers), Sir; John Dowson (1871). "10. Jámi'u-t Tawáríkh, of Rashid-al-Din". The History of India, as Told by Its Own Historians. The Muhammadan Period (Vol 3.). London : Trübner & Co.

- Paul Lunde and Rosalind Mazzawi, A History of the World, Saudi Aramco World, January 1981, describing the copy now in the Khalil collection

- Folios from the Jami' al-tavarikh, Timeline of Art History, Metropolitan Museum of Art

- Edinburgh pages in an exhibition at Cambridge

- Online scan of the Edinburgh manuscript