Japanese military modernization of 1868–1931

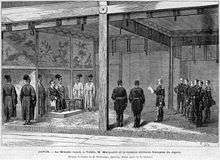

The modernization of the Japanese army and navy during the Meiji period (1868–1912) and until the Mukden Incident (1931) was carried out by the newly founded national government, a military leadership that was only responsible to the Emperor and the help of France, Britain, and later Germany.

When Western powers began to use their superior military strength to press Japan for trade relations in the 1850s, the country's decentralized and, by Western standards, antiquated military forces were unable to provide an effective defense against their advances. After the fall of the Tokugawa shogunate in 1867 and the restoration of the Meiji Emperor, de facto political and administrative power shifted to a group of younger samurai who had been instrumental in forming the new system and were committed to modernizing the military. They introduced drastic changes, which cleared the way for the development of modern, European-style armed forces.

Conscription became universal and obligatory in 1872 and, although samurai wedded to the traditional prerogatives of their class resisted, by 1880 a conscript army was firmly established. The Imperial Army General Staff Office, created after the Prussian model of the Generalstab, was established directly under the emperor in 1878 and was given broad powers for military planning and strategy. The new force eventually made the samurai spirit its own. Loyalties formerly accorded to feudal lords were transferred to the state and to the emperor. Upon release from service, soldiers carried these ideals back to their home communities, extending military-derived standards to all classes.

The Conscription Law established on January 10, 1873 made military service mandatory for all men in their twenties to enlist.[1] This legislation was the most significant military reform of the Meiji era. The samurai class no longer held a monopoly on military power; their benefits and status stripped from them after the Meiji Restoration. The dissolution of the samurai class would create a modern army of men of equal status. However, many of the samurai were unhappy with reforms and openly shared their concerns.

The conscription law was a way of social control; placing the unruly samurai class back into their roles as warriors. The Japanese government intended that the conscription would build a modern army capable of standing against the armies of Europe. However, the Meiji Restoration initially caused dissent among the dissolved samurai class but the conscription system was a way of stabilizing that dissent. Some of the samurai, more disgruntled than the others, formed pockets of resistance in order to circumvent the mandatory military service, many committed self-mutilation or openly rebelled.[2] They expressed their displeasure, because rejecting Western culture “became a way of demonstrating one's commitment” to the ways of the earlier Tokugawa era.[3]

The law also allowed the military to educate the enlisted. With the swing towards urbanization the government was concerned with having their population’s education lagging behind, most commoners illiterate and unknowing. The military provided “fresh opportunities for education” and for career advancement.[4] The “raw recruits would, especially in the first years of conscription, learn how to read.”[5] The government realized that an educated soldier could become a productive member of society, education was for the betterment of the state.

For the men to serve in the army, they were required to submit to a medical examination. This conscription exam measured height, weight and included an inspection of the candidate’s genitals. Those unable to pass the exam, the “congenitally weak, inveterately diseased, or deformed” were sent back to their families.[6] The exam “divided the citizenry into those who were fit for duty and those who were not.”[7] There was no material penalty for failing the exam but those that were unable to serve could be marginalized by society.

An imperial rescript of 1882 called for unquestioning loyalty to the emperor by the new armed forces and asserted that commands from superior officers were equivalent to commands from the emperor himself. Thenceforth, the military existed in an intimate and privileged relationship with the imperial institution. Top-ranking military leaders were given direct access to the emperor and the authority to transmit his pronouncements directly to the troops. The sympathetic relationship between conscripts and officers, particularly junior officers who were drawn mostly from the peasantry, tended to draw the military closer to the people. In time, most people came to look more for guidance in national matters to military commanders than to political leaders.

The first test of the nation's new military capabilities, a successful punitive expedition to Taiwan in 1874 in retaliation for the 1871 murder of shipwrecked sailors from Ryūkyū, was followed by a series of military ventures unmarred by defeat until World War II. Japan moved against Korea and China (First Sino-Japanese War), and Russia (Russo-Japanese War) to secure by military means the raw materials and strategic territories it believed necessary for the development and protection of the homeland. Territorial gains were achieved in Korea, the southern half of Sakhalin (named Karafuto in Japanese), and Manchuria. As an ally of Britain in World War I, Japan assumed control over Germany's possessions in Asia in the Treaty of Versailles, notably in China's Shandong Province, and the German-controlled Mariana, Caroline, and Marshall islands in the Pacific Ocean.

The Naval General Staff, independent from the supreme command from 1893, became even more powerful after World War I. At the 1921–22 Washington Naval Conference, the major powers signed the Five Power Naval Disarmament Treaty, which set the international capital ship ratio for the United States, Britain, Japan, France, and Italy at 5, 5, 3, 1.75, and 1.75, respectively. The Imperial Navy insisted that it required a ratio of seven ships for every eight United States naval ships but settled for three to five, a ratio acceptable to the Japanese public. The London Naval Treaty of 1930 brought about further reductions, but by the end of 1935, Japan had entered a period of unlimited military expansion and ignored its previous commitments. By the late 1930s, the proportion of Japanese to United States naval forces was 70.6 percent in total tonnage and 94 percent in aircraft carriers, and Japanese ships slightly outnumbered those of the United States.

References

-

This article incorporates public domain material from the Library of Congress Country Studies website http://lcweb2.loc.gov/frd/cs/. – Japan

This article incorporates public domain material from the Library of Congress Country Studies website http://lcweb2.loc.gov/frd/cs/. – Japan - [1] Yasuma Takata and Gotaro Ogawa, Conscription System in Japan (New York: University of Oxford Press, 1921), 10.

- [2] Hyman Kublin, “The “Modern” Army of Early Meiji Japan.” The Far Eastern Quarterly 9, no. 1 (1949): 32.

- [3] Jason G. Karlin, “The Gender of Nationalism: Competing Masculinities in Meiji Japan.” Journal of Japanese Studies 28, no. 1 (2002): 42.

- [4] Hyman Kublin, “The “Modern” Army of Early Meiji Japan.” The Far Eastern Quarterly 9, no. 1 (1949): 46.

- [5] E. Herbert Norman, Soldier and Peasant in Japan: The Origins of Conscription, (Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Press, 1997), 46.

- [6] Yasuma Takata and Gotaro Ogawa, Conscription System in Japan (New York: University of Oxford Press, 1921), 14.

- [7] Teresa A. Algoso, “Not Suitable as a Man: Conscription, Masculinity, and Hermaphroditism in Early Twentieth-Century Japan.” In Sabine Fruhstuck and Anne Walthall, eds., 248.