Samurai

Samurai (侍) were the military nobility and officer caste of medieval and early-modern Japan.

In Japanese, they are usually referred to as bushi (武士, [bu.ɕi]) or buke (武家). According to translator William Scott Wilson: "In Chinese, the character 侍 was originally a verb meaning "to wait upon" or "accompany persons" in the upper ranks of society, and this is also true of the original term in Japanese, saburau. In both countries the terms were nominalized to mean "those who serve in close attendance to the nobility", the pronunciation in Japanese changing to saburai. According to Wilson, an early reference to the word "samurai" appears in the Kokin Wakashū (905–914), the first imperial anthology of poems, completed in the first part of the 10th century.[1]

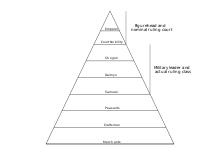

By the end of the 12th century, samurai became almost entirely synonymous with bushi, and the word was closely associated with the middle and upper echelons of the warrior class. The samurai were usually associated with a clan and their lord, were trained as officers in military tactics and grand strategy. While the samurai numbered less than 10% of then Japan's population,[2] their teachings can still be found today in both everyday life and in modern Japanese martial arts.

History

Asuka and Nara periods

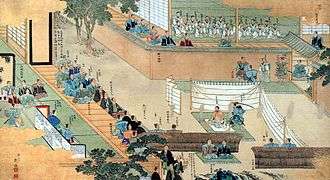

Following the Battle of Hakusukinoe against Tang China and Silla in 663 AD, which led to a retreat from Korean affairs, Japan underwent widespread reform. One of the most important was that of the Taika Reform, issued by Prince Naka-no-Ōe (Emperor Tenji) in 646 AD. This edict allowed the Japanese aristocracy to adopt the Tang dynasty political structure, bureaucracy, culture, religion, and philosophy.[3] As part of the Taihō Code of 702 AD, and the later Yōrō Code,[4] the population was required to report regularly for census, a precursor for national conscription. With an understanding of how the population was distributed, Emperor Monmu introduced a law whereby 1 in 3–4 adult males was drafted into the national military. These soldiers were required to supply their own weapons, and in-return were exempted from duties and taxes.[3] This was one of the first attempts by the Imperial government to form an organized army modeled after the Chinese system. It was called "Gundan-Sei" (ja:軍団制) by later historians and is believed to have been short-lived.

The Taihō Code classified most of the Imperial bureaucrats into 12 ranks, each divided into two sub-ranks, 1st rank being the highest adviser to the Emperor. Those of 6th rank and below were referred to as "samurai" and dealt with day-to-day affairs. Although these "samurai" were civilian public servants, the modern word is believed to have derived from this term. Military men, however, would not be referred to as "samurai" for many more centuries.

Heian period

In the early Heian period, during the late 8th and early 9th centuries, Emperor Kanmu sought to consolidate and expand his rule in northern Honshū, and sent military campaigns against the Emishi, who resisted the governance of the Kyoto-based imperial court. Emperor Kammu introduced the title of sei'i-taishōgun (征夷大将軍), or Shogun, and began to rely on the powerful regional clans to conquer the Emishi. Skilled in mounted combat and archery (kyūdō), these clan warriors became the Emperor's preferred tool for putting down rebellions; the most well known of which was Sakanoue no Tamuramaro. Though this is the first known use of the "Shogun" title, it was a temporary title, and was not imbued with political power until the 13th century. At this time (the 7th to 9th century), the Imperial Court officials considered them to be merely a military section under the control of the Imperial Court.

Ultimately, Emperor Kammu disbanded his army. From this time, the Emperor's power gradually declined. While the Emperor was still the ruler, powerful clans around Kyoto assumed positions as ministers, and their relatives bought positions as magistrates. To amass wealth and repay their debts, magistrates often imposed heavy taxes, resulting in many farmers becoming landless. Through protective agreements and political marriages, they accumulated, or gathered, political power, eventually surpassing the traditional aristocracy.

Some clans were originally formed by farmers who had taken up arms to protect themselves from the Imperial magistrates sent to govern their lands and collect taxes. These clans formed alliances to protect themselves against more powerful clans, and by the mid-Heian period they had adopted characteristic Japanese armor and weapons.

Late Heian Period, Kamakura Bakufu, and the rise of samurai

Originally the Emperor and non-warrior nobility employed these warrior nobles. In time, they amassed enough manpower, resources and political backing in the form of alliances with one another, to establish the first samurai-dominated government. As the power of these regional clans grew, their chief was typically a distant relative of the Emperor and a lesser member of either the Fujiwara, Minamoto, or Taira clans. Though originally sent to provincial areas for a fixed four-year term as a magistrate, the toryo declined to return to the capital when their terms ended, and their sons inherited their positions and continued to lead the clans in putting down rebellions throughout Japan during the middle- and later-Heian period. Because of their rising military and economic power, the warriors ultimately became a new force in the politics of the Imperial court. Their involvement in the Hōgen Rebellion in the late Heian period consolidated their power, which later pitted the rivalry of Minamoto and Taira clans against each other in the Heiji Rebellion of 1160.

The victor, Taira no Kiyomori, became an imperial advisor, and was the first warrior to attain such a position. He eventually seized control of the central government, establishing the first samurai-dominated government and relegating the Emperor to figurehead status. However, the Taira clan was still very conservative when compared to its eventual successor, the Minamoto, and instead of expanding or strengthening its military might, the clan had its women marry Emperors and exercise control through the Emperor.

The Taira and the Minamoto clashed again in 1180, beginning the Genpei War, which ended in 1185. Samurai fought at the naval battle of Dan-no-ura, at the Shimonoseki Strait which separates Honshu and Kyushu in 1185. The victorious Minamoto no Yoritomo established the superiority of the samurai over the aristocracy. In 1190 he visited Kyoto and in 1192 became Sei'i-taishōgun, establishing the Kamakura Shogunate, or Kamakura Bakufu. Instead of ruling from Kyoto, he set up the Shogunate in Kamakura, near his base of power. "Bakufu" means "tent government", taken from the encampments the soldiers would live in, in accordance with the Bakufu's status as a military government.[5]

After the Genpei war, Yoritomo obtained the right to appoint shugo and jitō, and was allowed to organize soldiers and police, and to collect a certain amount of tax. Initially, their responsibility was restricted to arresting rebels and collecting needed army provisions, and they were forbidden from interfering with Kokushi officials, but their responsibility gradually expanded. Thus, the samurai-class appeared as the political ruling power in Japan.

Ashikaga Shogunate

Various samurai clans struggled for power during the Kamakura and Ashikaga Shogunates. Zen Buddhism spread among the samurai in the 13th century and helped to shape their standards of conduct, particularly overcoming fear of death and killing, but among the general populace, Pure Land Buddhism was favored.

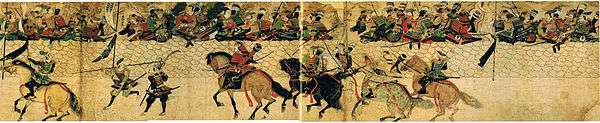

In 1274, the Mongol-founded Yuan dynasty in China sent a force of some 40,000 men and 900 ships to invade Japan in northern Kyūshū. Japan mustered a mere 10,000 samurai to meet this threat. The invading army was harassed by major thunderstorms throughout the invasion, which aided the defenders by inflicting heavy casualties. The Yuan army was eventually recalled and the invasion was called off. The Mongol invaders used small bombs, which was likely the first appearance of bombs and gunpowder in Japan.

The Japanese defenders recognized the possibility of a renewed invasion, and began construction of a great stone barrier around Hakata Bay in 1276. Completed in 1277, this wall stretched for 20 kilometers around the border of the bay. This would later serve as a strong defensive point against the Mongols. The Mongols attempted to settle matters in a diplomatic way from 1275 to 1279, but every envoy sent to Japan was executed. This set the stage for one of the most famous engagements in Japanese history.

In 1281, a Yuan army of 140,000 men with 5,000 ships was mustered for another invasion of Japan. Northern Kyūshū was defended by a Japanese army of 40,000 men. The Mongol army was still on its ships preparing for the landing operation when a typhoon hit north Kyūshū island. The casualties and damage inflicted by the typhoon, followed by the Japanese defense of the Hakata Bay barrier, resulted in the Mongols again recalling their armies.

The thunderstorms of 1274 and the typhoon of 1281 helped the samurai defenders of Japan repel the Mongol invaders despite being vastly outnumbered. These winds became known as kami-no-kaze, which literally translates as "wind of the gods". This is often given a simplified translation as "divine wind". The kami-no-kaze lent credence to the Japanese belief that their lands were indeed divine and under supernatural protection.

In the 14th century, a blacksmith called Masamune developed a two-layer structure of soft and hard steel for use in swords. This structure gave much improved cutting power and endurance, and the production technique led to Japanese swords (katana) being recognized as some of the most potent hand weapons of pre-industrial East Asia. Many swords made using this technique were exported across the East China Sea, a few making their way as far as India.

Issues of inheritance caused family strife as primogeniture became common, in contrast to the division of succession designated by law before the 14th century. To avoid infighting, invasions of neighboring samurai territories became common and bickering among samurai was a constant problem for the Kamakura and Ashikaga shogunates.

Sengoku period

The Sengoku jidai ("warring-states period") was marked by the loosening of samurai culture with people born into other social strata sometimes making names for themselves as warriors and thus becoming de facto samurai.

Japanese war tactics and technologies improved rapidly in the 15th and 16th century. Use of large numbers of infantry called ashigaru ("light-foot", due to their light armor), formed of humble warriors or ordinary people with nagayari (a long lance) or (naginata), was introduced and combined with cavalry in maneuvers. The number of people mobilized in warfare ranged from thousands to hundreds of thousands.

The arquebus, a matchlock gun, was introduced by the Portuguese via a Chinese pirate ship in 1543 and the Japanese succeeded in assimilating it within a decade. Groups of mercenaries with mass-produced arquebuses began playing a critical role. By the end of the Sengoku period, several hundred thousand firearms existed in Japan and massive armies numbering over 100,000 clashed in battles.

Azuchi–Momoyama period

In 1592, and again in 1597, Toyotomi Hideyoshi, aiming to invade China (唐入り) through Korea, mobilized an army of 160,000 peasants and samurai and deployed them to Korea. (See Hideyoshi's invasions of Korea, Chōsen-seibatsu (朝鮮征伐). Taking advantage of arquebus mastery and extensive wartime experience from the Sengoku period, Japanese samurai armies made major gains in most of Korea. Katō Kiyomasa advanced to Orangkai territory (present-day Manchuria) bordering Korea to the northeast and crossed the border into Manchuria, but withdrew after retaliatory attacks from the Jurchens there, as it was clear he had outpaced the rest of the Japanese invasion force. A few of the more famous samurai generals of this war were Katō Kiyomasa, Konishi Yukinaga, and Shimazu Yoshihiro. Shimazu Yoshihiro led some 7,000 samurai and, despite being heavily outnumbered, defeated a host of allied Ming and Korean forces at the Battle of Sacheon in 1598, near the conclusion of the campaigns. Yoshihiro was feared as Oni-Shimazu ("Shimazu ogre") and his nickname spread across not only Korea but to Ming Dynasty China. In spite of the superiority of Japanese land forces, ultimately the two expeditions failed (though they did devastate the Korean landmass) from factors such as Korean naval superiority (which, led by Admiral Yi Sun-sin, harassed Japanese supply lines continuously throughout the wars, resulting in supply shortages on land), the commitment of sizeable Ming forces to Korea, Korean guerrilla actions, the underestimation of resistance by Japanese commanders (in the first campaign of 1592, Korean defenses on land were caught unprepared, under-trained, and under-armed; they were rapidly overrun, with only a limited number of successfully resistant engagements against the more-experienced and battle-hardened Japanese forces – in the second campaign of 1597, Korean and Ming forces proved to be a far more difficult challenge and, with the support of continued Korean naval superiority, limited Japanese gains to parts southeastern Korea), and wavering Japanese commitment to the campaigns as the wars dragged on. The final death blow to the Japanese campaigns in Korea came with Hideyoshi's death in late 1598 and the recall of all Japanese forces in Korea by the Council of Five Elders (established by Hideyoshi to oversee the transition from his regency to that of his son Hideyori).

Many samurai forces that were active throughout this period were not deployed to Korea; most importantly, the daimyōs Tokugawa Ieyasu carefully kept forces under his command out of the Korean campaigns, and other samurai commanders who were opposed to Hideyoshi's domination of Japan either mulled Hideyoshi's call to invade Korea or contributed a small token force. Most commanders who did opposed or otherwise resisted or resented Hideyoshi ended up as part of the so-called Eastern Army, while commanders loyal to Hideyoshi and his son (a notable exception to this trend was Katō Kiyomasa, who deployed with Tokugawa and the Eastern Army) were largely committed to the Western Army; the two opposing sides (so named for the relative geographical locations of their respective commanders' domains) would later clash, most notably at the Battle of Sekigahara, which was won by Tokugawa Ieyasu and the Eastern Forces, paving the way for the establishment of the Tokugawa Shogunate.

Social mobility was high, as the ancient regime collapsed and emerging samurai needed to maintain large military and administrative organizations in their areas of influence. Most of the samurai families that survived to the 19th century originated in this era, declaring themselves to be the blood of one of the four ancient noble clans: Minamoto, Taira, Fujiwara and Tachibana. In most cases, however, it is hard to prove these claims.

Oda, Toyotomi and Tokugawa

Oda Nobunaga was the well-known lord of the Nagoya area (once called Owari Province) and an exceptional example of a samurai of the Sengoku period.[6] He came within a few years of, and laid down the path for his successors to follow, the reunification of Japan under a new Bakufu (Shogunate).

Oda Nobunaga made innovations in the fields of organization and war tactics, heavily used arquebuses, developed commerce and industry and treasured innovation. Consecutive victories enabled him to realize the termination of the Ashikaga Bakufu and the disarmament of the military powers of the Buddhist monks, which had inflamed futile struggles among the populace for centuries. Attacking from the "sanctuary" of Buddhist temples, they were constant headaches to any warlord and even the Emperor who tried to control their actions. He died in 1582 when one of his generals, Akechi Mitsuhide, turned upon him with his army.

Importantly, Toyotomi Hideyoshi (see below) and Tokugawa Ieyasu, who founded the Tokugawa Shogunate, were loyal followers of Nobunaga. Hideyoshi began as a peasant and became one of Nobunaga's top generals, and Ieyasu had shared his childhood with Nobunaga. Hideyoshi defeated Mitsuhide within a month, and was regarded as the rightful successor of Nobunaga by avenging the treachery of Mitsuhide.

These two were able to use Nobunaga's previous achievements on which build a unified Japan and there was a saying: "The reunification is a rice cake; Oda made it. Hashiba shaped it. At last, only Ieyasu tastes it." (Hashiba is the family name that Toyotomi Hideyoshi used while he was a follower of Nobunaga.)

Toyotomi Hideyoshi, who became a grand minister in 1586, himself the son of a poor peasant family, created a law that the samurai caste became codified as permanent and hereditary, and that non-samurai were forbidden to carry weapons, thereby ending the social mobility of Japan up until that point, which lasted until the dissolution of the Edo Shogunate by the Meiji revolutionaries.

It is important to note that the distinction between samurai and non-samurai was so obscure that during the 16th century, most male adults in any social class (even small farmers) belonged to at least one military organization of their own and served in wars before and during Hideyoshi's rule. It can be said that an "all against all" situation continued for a century.

The authorized samurai families after the 17th century were those that chose to follow Nobunaga, Hideyoshi and Ieyasu. Large battles occurred during the change between regimes, and a number of defeated samurai were destroyed, went rōnin or were absorbed into the general populace.

Tokugawa Shogunate

During the Tokugawa shogunate, samurai increasingly became courtiers, bureaucrats, and administrators rather than warriors. With no warfare since the early 17th century, samurai gradually lost their military function during the Tokugawa era (also called the Edo period). By the end of the Tokugawa era, samurai were aristocratic bureaucrats for the daimyōs, with their daishō, the paired long and short swords of the samurai (cf. katana and wakizashi) becoming more of a symbolic emblem of power rather than a weapon used in daily life. They still had the legal right to cut down any commoner who did not show proper respect kiri-sute gomen (斬り捨て御免), but to what extent this right was used is unknown. When the central government forced daimyos to cut the size of their armies, unemployed rōnin became a social problem.

Theoretical obligations between a samurai and his lord (usually a daimyō) increased from the Genpei era to the Edo era. They were strongly emphasized by the teachings of Confucius and Mencius (ca 550 BC), which were required reading for the educated samurai class.

The conduct of samurai served as role model behavior for the other social classes. With time on their hands, samurai spent more time in pursuit of other interests such as becoming scholars.

Modernization

The relative peace of the Tokugawa era was shattered with the arrival of Commodore Matthew Perry's massive U.S. Navy steamships in 1853. Perry used his superior firepower to force Japan to open its borders to trade. Prior to that only a few harbor towns, under strict control from the Shogunate, were allowed to participate in Western trade, and even then, it was based largely on the idea of playing the Franciscans and Dominicans off against one another (in exchange for the crucial arquebus technology, which in turn was a major contributor to the downfall of the classical samurai).

From 1854, the samurai army and the navy were modernized. A Naval training school was established in Nagasaki in 1855. Naval students were sent to study in Western naval schools for several years, starting a tradition of foreign-educated future leaders, such as Admiral Enomoto. French naval engineers were hired to build naval arsenals, such as Yokosuka and Nagasaki. By the end of the Tokugawa shogunate in 1867, the Japanese navy of the shogun already possessed eight western-style steam warships around the flagship Kaiyō Maru, which were used against pro-imperial forces during the Boshin War, under the command of Admiral Enomoto. A French Military Mission to Japan (1867) was established to help modernize the armies of the Bakufu.

The last showing of the original samurai was in 1867 when samurai from Chōshū and Satsuma provinces defeated the Shogunate forces in favor of the rule of the Emperor in the Boshin War (1868–1869). The two provinces were the lands of the daimyo that submitted to Ieyasu after the Battle of Sekigahara (1600).

Decline

Emperor Meiji abolished the samurai's right to be the only armed force in favor of a more modern, western-style, conscripted army in 1873. Samurai became Shizoku (士族) who retained some of their salaries, but the right to wear a katana in public was eventually abolished along with the right to execute commoners who paid them disrespect. The samurai finally came to an end after hundreds of years of enjoyment of their status, their powers, and their ability to shape the government of Japan. However, the rule of the state by the military class was not yet over. In defining how a modern Japan should be, members of the Meiji government decided to follow the footsteps of the United Kingdom and Germany, basing the country on the concept of noblesse oblige. Samurai were not a political force under the new order. With the Meiji reforms in the late 19th century, the samurai class was abolished, and a western-style national army was established. The Imperial Japanese Armies were conscripted, but many samurai volunteered as soldiers, and many advanced to be trained as officers. Much of the Imperial Army officer class was of samurai origin, and were highly motivated, disciplined, and exceptionally trained.

The last samurai conflict was arguably in 1877, during the Satsuma Rebellion in the Battle of Shiroyama. This conflict had its genesis in the previous uprising to defeat the Tokugawa Shogunate, leading to the Meiji Restoration. The newly formed government instituted radical changes, aimed at reducing the power of the feudal domains, including Satsuma, and the dissolution of samurai status. This led to the ultimately premature uprising, led by Saigō Takamori.

Samurai were many of the early exchange students, not directly because they were samurai, but because many samurai were literate and well-educated scholars. Some of these exchange students started private schools for higher educations, while many samurai took pens instead of guns and became reporters and writers, setting up newspaper companies, and others entered governmental service. Some samurai became businessmen. For example, Iwasaki Yatarō, who was the great-grandson of a samurai, established Mitsubishi.

Only the name Shizoku existed after that. After Japan lost World War II, the name Shizoku disappeared under the law on 1 January 1947.

Philosophy

Religious influences

The philosophies of Buddhism and Zen, and to a lesser extent Confucianism and Shinto, influenced the samurai culture. Zen meditation became an important teaching due to it offering a process to calm one's mind. The Buddhist concept of reincarnation and rebirth led samurai to abandon torture and needless killing, while some samurai even gave up violence altogether and became Buddhist monks after coming to believe that their killings were fruitless. Some were killed as they came to terms with these conclusions in the battlefield. The most defining role that Confucianism played in samurai philosophy was to stress the importance of the lord-retainer relationship—the loyalty that a samurai was required to show his lord.

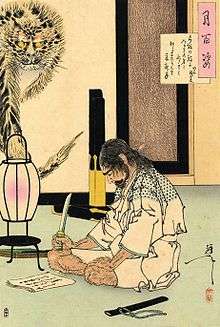

After the Japanese defeat of China in 1895 and of Russia in 1905, nationalists began to propagte a purportedly ancient samurai code they called bushidō ("way of the warrior") as part of a nihonjinron theory of Japanese exceptionalism; the term and concept are rare in pre-20th century literature.[7] Hagakure or "Hidden in Leaves" by Yamamoto Tsunetomo and Gorin no Sho or "Book of the Five Rings" by Miyamoto Musashi, both written in the Tokugawa period (1603–1868), are theories that have been associated with bushidō and Zen philosophy.

The philosophies of Buddhism and Zen, and to a lesser extent Confucianism and Shinto, are attributed to the development of the samurai culture. According to Robert Sharf, "The notion that Zen is somehow related to Japanese culture in general, and bushidō in particular, is familiar to Western students of Zen through the writings of D. T. Suzuki, no doubt the single most important figure in the spread of Zen in the West."[8]

In an account of Japan sent to Father Ignatius Loyola at Rome, drawn from the statements of Anger (Han-Siro's western name), Xavier describes the importance of honor to the Japanese (Letter preserved at College of Coimbra.):

In the first place, the nation with which we have had to do here surpasses in goodness any of the nations lately discovered. I really think that among barbarous nations there can be none that has more natural goodness than the Japanese. They are of a kindly disposition, not at all given to cheating, wonderfully desirous of honour and rank. Honour with them is placed above everything else. There are a great many poor among them, but poverty is not a disgrace to any one. There is one thing among them of which I hardly know whether it is practised anywhere among Christians. The nobles, however poor they may be, receive the same honour from the rest as if they were rich.[9]

Doctrine

Bushidō is defined by the Japanese dictionary Shogakukan Kokugo Daijiten as "a unique philosophy (ronri) that spread through the warrior class from the Muromachi (chusei) period. From the earliest times, the Samurai felt that the path of the warrior was one of honor, emphasizing duty to one's master, and loyalty unto death".[10]

In the 13th century, Hōjō Shigetoki (1198–1261 AD) wrote: "When one is serving officially or in the master's court, he should not think of a hundred or a thousand people, but should consider only the importance of the master."[11] Carl Steenstrup noted that 13th and 14th century warrior writings (gunki) "portrayed the bushi in their natural element, war, eulogizing such virtues as reckless bravery, fierce family pride, and selfless, at times senseless devotion of master and man".[12] Feudal lords such as Shiba Yoshimasa (1350–1410) stated that a warrior looked forward to a glorious death in the service of a military leader or the Emperor: "It is a matter of regret to let the moment when one should die pass by ... First, a man whose profession is the use of arms should think and then act upon not only his own fame, but also that of his descendants. He should not scandalize his name forever by holding his one and only life too dear ... One's main purpose in throwing away his life is to do so either for the sake of the Emperor or in some great undertaking of a military general. It is that exactly that will be the great fame of one's descendants."[13]

In 1412 AD, Imagawa Sadayo wrote a letter of admonishment to his brother stressing the importance of duty to one's master. Imagawa was admired for his balance of military and administrative skills during his lifetime and his writings became widespread. The letters became central to Tokugawa-era laws and were a required study for traditional Japanese until World War II:

"First of all, a samurai who dislikes battle and has not put his heart in the right place even though he has been born in the house of the warrior, should not be reckoned among one's retainers ... It is forbidden to forget the great debt of kindness one owes to his master and ancestors and thereby make light of the virtues of loyalty and filial piety ... It is forbidden that one should ... attach little importance to his duties to his master ... There is a primary need to distinguish loyalty from disloyalty and to establish rewards and punishments."[14]

Similarly, the feudal lord Takeda Nobushige (1525–1561) stated: "In matters both great and small, one should not turn his back on his master's commands ... One should not ask for gifts or enfiefments from the master ... No matter how unreasonably the master may treat a man, he should not feel disgruntled ... An underling does not pass judgments on a superior"[15]

Nobushige's brother Takeda Shingen (1521–1573) also made similar observations: "One who was born in the house of a warrior, regardless of his rank or class, first acquaints himself with a man of military feats and achievements in loyalty ... Everyone knows that if a man doesn't hold filial piety toward his own parents he would also neglect his duties toward his lord. Such a neglect means a disloyalty toward humanity. Therefore such a man doesn't deserve to be called 'samurai'."[16]

The feudal lord Asakura Yoshikage (1428–1481) wrote: "In the fief of the Asakura, one should not determine hereditary chief retainers. A man should be assigned according to his ability and loyalty." Asakura also observed that the successes of his father were obtained by the kind treatment of the warriors and common people living in domain. By his civility, "all were willing to sacrifice their lives for him and become his allies."[17]

Katō Kiyomasa was one of the most powerful and well-known lords of the Sengoku Era. He commanded most of Japan's major clans during the invasion of Korea (1592–1598). In a handbook he addressed to "all samurai, regardless of rank" he told his followers that a warrior's only duty in life was to "grasp the long and the short swords and to die". He also ordered his followers to put forth great effort in studying the military classics, especially those related to loyalty and filial piety. He is best known for his quote:[18] "If a man does not investigate into the matter of Bushido daily, it will be difficult for him to die a brave and manly death. Thus it is essential to engrave this business of the warrior into one's mind well."

Nabeshima Naoshige (1538–1618 AD) was another Sengoku Daimyo who fought alongside Kato Kiyomasa in Korea. He stated that it was shameful for any man to have not risked his life at least once in the line of duty, regardless of his rank. Nabeshima's sayings would be passed down to his son and grandson and would become the basis for Tsunetomo Yamamoto's Hagakure. He is best known for his saying "The way of the Samurai is in desperateness. Ten men or more cannot kill such a man."[19][20]

Torii Mototada (1539–1600) was a feudal lord in the service of Tokugawa Ieyasu. On the eve of the battle of Sekigahara, he volunteered to remain behind in the doomed Fushimi Castle while his lord advanced to the east. Torii and Tokugawa both agreed that the castle was indefensible. In an act of loyalty to his lord, Torii chose to remain behind, pledging that he and his men would fight to the finish. As was custom, Torii vowed that he would not be taken alive. In a dramatic last stand, the garrison of 2,000 men held out against overwhelming odds for ten days against the massive army of Ishida Mitsunari's 40,000 warriors. In a moving last statement to his son Tadamasa, he wrote:[21]

"It is not the Way of the Warrior [i.e., bushidō] to be shamed and avoid death even under circumstances that are not particularly important. It goes without saying that to sacrifice one's life for the sake of his master is an unchanging principle. That I should be able to go ahead of all the other warriors of this country and lay down my life for the sake of my master's benevolence is an honor to my family and has been my most fervent desire for many years."

It is said that both men cried when they parted ways, because they knew they would never see each other again. Torii's father and grandfather had served the Tokugawa before him and his own brother had already been killed in battle. Torii's actions changed the course of Japanese history. Ieyasu Tokugawa would successfully raise an army and win at Sekigahara.

The translator of Hagakure, William Scott Wilson observed examples of warrior emphasis on death in clans other than Yamamoto's: "he (Takeda Shingen) was a strict disciplinarian as a warrior, and there is an exemplary story in the Hagakure relating his execution of two brawlers, not because they had fought, but because they had not fought to the death".[22][23]

The rival of Takeda Shingen (1521–1573) was Uesugi Kenshin (1530–1578), a legendary Sengoku warlord well-versed in the Chinese military classics and who advocated the "way of the warrior as death". Japanese historian Daisetz Teitaro Suzuki describes Uesugi's beliefs as: "Those who are reluctant to give up their lives and embrace death are not true warriors ... Go to the battlefield firmly confident of victory, and you will come home with no wounds whatever. Engage in combat fully determined to die and you will be alive; wish to survive in the battle and you will surely meet death. When you leave the house determined not to see it again you will come home safely; when you have any thought of returning you will not return. You may not be in the wrong to think that the world is always subject to change, but the warrior must not entertain this way of thinking, for his fate is always determined."[24]

Families such as the Imagawa were influential in the development of warrior ethics and were widely quoted by other lords during their lifetime. The writings of Imagawa Sadayo were highly respected and sought out by Tokugawa Ieyasu as the source of Japanese Feudal Law. These writings were a required study among traditional Japanese until World War II.

Historian H. Paul Varley notes the description of Japan given by Jesuit leader St. Francis Xavier (1506–1552): "There is no nation in the world which fears death less." Xavier further describes the honour and manners of the people: "I fancy that there are no people in the world more punctilious about their honour than the Japanese, for they will not put up with a single insult or even a word spoken in anger." Xavier spent the years 1549–1551 converting Japanese to Christianity. He also observed: "The Japanese are much braver and more warlike than the people of China, Korea, Ternate and all of the other nations around the Philippines."[25]

Arts

In December 1547, Francis was in Malacca (Malaysia) waiting to return to Goa (India) when he met a low-ranked samurai named Anjiro (possibly spelled "Yajiro"). Anjiro was not an intellectual, but he impressed Xavier because he took careful notes of everything he said in church. Xavier made the decision to go to Japan in part because this low-ranking samurai convinced him in Portuguese that the Japanese people were highly educated and eager to learn. They were hard workers and respectful of authority. In their laws and customs they were led by reason, and, should the Christian faith convince them of its truth, they would accept it en masse.[26]

By the 12th century, upper-class samurai were highly literate due to the general introduction of Confucianism from China during the 7th to 9th centuries, and in response to their perceived need to deal with the imperial court, who had a monopoly on culture and literacy for most of the Heian period. As a result, they aspired to the more cultured abilities of the nobility.[27]

Examples such as Taira Tadanori (a samurai who appears in the Heike Monogatari) demonstrate that warriors idealized the arts and aspired to become skilled in them.

Tadanori was famous for his skill with the pen and the sword or the "bun and the bu", the harmony of fighting and learning. Samurai were expected to be cultured and literate, and admired the ancient saying "bunbu-ryōdō" (文武両道, lit., literary arts, military arts, both ways) or "The pen and the sword in accord". By the time of the Edo period, Japan had a higher literacy comparable to that in central Europe.[28]

The number of men who actually achieved the ideal and lived their lives by it was high. An early term for warrior, "uruwashii", was written with a kanji that combined the characters for literary study ("bun" 文) and military arts ("bu" 武), and is mentioned in the Heike Monogatari (late 12th century). The Heike Monogatari makes reference to the educated poet-swordsman ideal in its mention of Taira no Tadanori's death:[29]

Friends and foes alike wet their sleeves with tears and said,

What a pity! Tadanori was a great general,

pre-eminent in the arts of both sword and poetry.

In his book "Ideals of the Samurai" translator William Scott Wilson states: "The warriors in the Heike Monogatari served as models for the educated warriors of later generations, and the ideals depicted by them were not assumed to be beyond reach. Rather, these ideals were vigorously pursued in the upper echelons of warrior society and recommended as the proper form of the Japanese man of arms. With the Heike Monogatari, the image of the Japanese warrior in literature came to its full maturity."[29] Wilson then translates the writings of several warriors who mention the Heike Monogatari as an example for their men to follow.

Plenty of warrior writings document this ideal from the 13th century onward. Most warriors aspired to or followed this ideal otherwise there would have been no cohesion in the samurai armies.[30]

Culture

As aristocrats for centuries, samurai developed their own cultures that influenced Japanese culture as a whole. The culture associated with the samurai such as the tea ceremony, monochrome ink painting, rock gardens and poetry were adopted by warrior patrons throughout the centuries 1200–1600. These practices were adapted from the Chinese arts. Zen monks introduced them to Japan and they were allowed to flourish due to the interest of powerful warrior elites. Musō Soseki (1275–1351) was a Zen monk who was advisor to both Emperor Go-Daigo and General Ashikaga Takauji (1304–58). Musō, as well as other monks, acted as political and cultural diplomat between Japan and China. Musō was particularly well known for his garden design. Another Ashikaga patron of the arts was Yoshimasa. His cultural advisor, the Zen monk Zeami, introduced tea ceremony to him. Previously, tea had been used primarily for Buddhist monks to stay awake during meditation.[31]

Education

In general, samurai, aristocrats, and priests had a very high literacy rate in kanji. Recent studies have shown that literacy in kanji among other groups in society was somewhat higher than previously understood. For example, court documents, birth and death records and marriage records from the Kamakura period, submitted by farmers, were prepared in Kanji. Both the kanji literacy rate and skills in math improved toward the end of Kamakura period.[27]

Literacy was generally high among the warriors and the common classes as well. The feudal lord Asakura Norikage (1474–1555 AD) noted the great loyalty given to his father, due to his polite letters, not just to fellow samurai, but also to the farmers and townspeople:

There were to Lord Eirin's character many high points difficult to measure, but according to the elders the foremost of these was the way he governed the province by his civility. It goes without saying that he acted this way toward those in the samurai class, but he was also polite in writing letters to the farmers and townspeople, and even in addressing these letters he was gracious beyond normal practice. In this way, all were willing to sacrifice their lives for him and become his allies.[32]

In a letter dated 29 January 1552, St Francis Xavier observed the ease of which the Japanese understood prayers due to the high level of literacy in Japan at that time:

There are two kinds of writing in Japan, one used by men and the other by women; and for the most part both men and women, especially of the nobility and the commercial class, have a literary education. The bonzes, or bonzesses, in their monasteries teach letters to the girls and boys, though rich and noble persons entrust the education of their children to private tutors.

Most of them can read, and this is a great help to them for the easy understanding of our usual prayers and the chief points of our holy religion.[33]

In a letter to Father Ignatius Loyola at Rome, Xavier further noted the education of the upper classes:

The Nobles send their sons to monasteries to be educated as soon as they are 8 years old, and they remain there until they are 19 or 20, learning reading, writing and religion; as soon as they come out, they marry and apply themselves to politics. They are discreet, magnanimous and lovers of virtue and letters, honouring learned men very much.

In a letter dated 11 November 1549, Xavier described a multi-tiered educational system in Japan consisting of "universities", "colleges", "academies" and hundreds of monasteries that served as a principle center for learning by the populace:

But now we must give you an account of our stay at Cagoxima. We put into that port because the wind was adverse to our sailing to Meaco, which is the largest city in Japan, and most famous as the residence of the King and the Princes. It is said that after four months are passed the favourable season for a voyage to Meaco will return, and then with the good help of God we shall sail thither. The distance from Cagoxima is three hundred leagues. We hear wonderful stories about the size of Meaco: they say that it consists of more than ninety thousand dwellings. There is a very famous University there, as well as five chief colleges of students, and more than two hundred monasteries of bonzes, and of others who are like coenobites, called Legioxi, as well as of women of the same kind, who are called Hamacutis. Besides this of Meaco, there are in Japan five other principal academies, at Coya, at Negu, at Fisso, and at Homia. These are situated round Meaco, with short distances between them, and each is frequented by about three thousand five hundred scholars. Besides these there is the Academy at Bandou, much the largest and most famous in all Japan, and at a great distance from Meaco. Bandou is a large territory, ruled by six minor princes, one of whom is more powerful than the others and is obeyed by them, being himself subject to the King of Japan, who is called the Great King of Meaco. The things that are given out as to the greatness and celebrity of these universities and cities are so wonderful as to make us think of seeing them first with our own eyes and ascertaining the truth, and then when we have discovered and know how things really are, of writing an account of them to you. They say that there are several lesser academies besides those which we have mentioned.

Names

A samurai was usually named by combining one kanji from his father or grandfather and one new kanji. Samurai normally used only a small part of their total name.

For example, the full name of Oda Nobunaga would be "Oda Kazusanosuke Saburo Nobunaga" (織田上総介三郎信長), in which "Oda" is a clan or family name, "Kazusanosuke" is a title of vice-governor of Kazusa province, "Saburo" is a formal nickname (yobina), and "Nobunaga" is an adult name (nanori) given at genpuku, the coming of age ceremony. A man was addressed by his family name and his title, or by his yobina if he did not have a title. However, the nanori was a private name that could be used by only a very few, including the Emperor.

Samurai could choose their own nanori, and frequently changed their names to reflect their allegiances.

Marriage

Samurai had arranged marriages, which were arranged by a go-between of the same or higher rank. While for those samurai in the upper ranks this was a necessity (as most had few opportunities to meet women), this was a formality for lower-ranked samurai. Most samurai married women from a samurai family, but for lower-ranked samurai, marriages with commoners were permitted. In these marriages a dowry was brought by the woman and was used to set up the couple's new household.

A samurai could take concubines but their backgrounds were checked by higher-ranked samurai. In many cases, taking a concubine was akin to a marriage. Kidnapping a concubine, although common in fiction, would have been shameful, if not criminal. If the concubine was a commoner, a messenger was sent with betrothal money or a note for exemption of tax to ask for her parents' acceptance. Even though the woman would not be a legal wife, a situation normally considered a demotion, many wealthy merchants believed that being the concubine of a samurai was superior to being the legal wife of a commoner. When a merchant's daughter married a samurai, her family's money erased the samurai's debts, and the samurai's social status improved the standing of the merchant family. If a samurai's commoner concubine gave birth to a son, the son could inherit his father's social status.

A samurai could divorce his wife for a variety of reasons with approval from a superior, but divorce was, while not entirely nonexistent, a rare event. A wife's failure to produce a son was cause for divorce, but adoption of a male heir was considered an acceptable alternative to divorce. A samurai could divorce for personal reasons, even if he simply did not like his wife, but this was generally avoided as it would embarrass the person who had arranged the marriage. A woman could also arrange a divorce, although it would generally take the form of the samurai divorcing her. After a divorce samurai had to return the betrothal money, which often prevented divorces.

Women

Maintaining the household was the main duty of samurai women. This was especially crucial during early feudal Japan, when warrior husbands were often traveling abroad or engaged in clan battles. The wife, or okugatasama (meaning: one who remains in the home), was left to manage all household affairs, care for the children, and perhaps even defend the home forcibly. For this reason, many women of the samurai class were trained in wielding a polearm called a naginata or a special knife called the kaiken in an art called tantojutsu (lit. the skill of the knife), which they could use to protect their household, family, and honor if the need arose.

Traits valued in women of the samurai class were humility, obedience, self-control, strength, and loyalty. Ideally, a samurai wife would be skilled at managing property, keeping records, dealing with financial matters, educating the children (and perhaps servants, too), and caring for elderly parents or in-laws that may be living under her roof. Confucian law, which helped define personal relationships and the code of ethics of the warrior class required that a woman show subservience to her husband, filial piety to her parents, and care to the children. Too much love and affection was also said to indulge and spoil the youngsters. Thus, a woman was also to exercise discipline.

Though women of wealthier samurai families enjoyed perks of their elevated position in society, such as avoiding the physical labor that those of lower classes often engaged in, they were still viewed as far beneath men. Women were prohibited from engaging in any political affairs and were usually not the heads of their household.

This does not mean that samurai women were always powerless. Powerful women both wisely and unwisely wielded power at various occasions. After Ashikaga Yoshimasa, 8th shogun of the Muromachi shogunate, lost interest in politics, his wife Hino Tomiko largely ruled in his place. Nene, wife of Toyotomi Hideyoshi, was known to overrule her husband's decisions at times and Yodo-dono, his concubine, became the de facto master of Osaka castle and the Toyotomi clan after Hideyoshi's death. Tachibana Ginchiyo was chosen to lead the Tachibana clan after her father's death. Chiyo, wife of Yamauchi Kazutoyo, has long been considered the ideal samurai wife. According to legend, she made her kimono out of a quilted patchwork of bits of old cloth and saved pennies to buy her husband a magnificent horse, on which he rode to many victories. The fact that Chiyo (though she is better known as "Wife of Yamauchi Kazutoyo") is held in such high esteem for her economic sense is illuminating in the light of the fact that she never produced an heir and the Yamauchi clan was succeeded by Kazutoyo's younger brother. The source of power for women may have been that samurai left their finances to their wives.

As the Tokugawa period progressed more value became placed on education, and the education of females beginning at a young age became important to families and society as a whole. Marriage criteria began to weigh intelligence and education as desirable attributes in a wife, right along with physical attractiveness. Though many of the texts written for women during the Tokugawa period only pertained to how a woman could become a successful wife and household manager, there were those that undertook the challenge of learning to read, and also tackled philosophical and literary classics. Nearly all women of the samurai class were literate by the end of the Tokugawa period.

Western samurai

The English sailor and adventurer William Adams (1564–1620) was the first Westerner to receive the dignity of samurai. The Shogun Tokugawa Ieyasu presented him with two swords representing the authority of a samurai, and decreed that William Adams the sailor was dead and that Anjin Miura (三浦按針), a samurai, was born. Adams also received the title of hatamoto (bannerman), a high-prestige position as a direct retainer in the Shogun's court. He was provided with generous revenues: "For the services that I have done and do daily, being employed in the Emperor's service, the Emperor has given me a living" (Letters). He was granted a fief in Hemi (逸見) within the boundaries of present-day Yokosuka City, "with eighty or ninety husbandmen, that be my slaves or servants" (Letters). His estate was valued at 250 koku. He finally wrote "God hath provided for me after my great misery", (Letters) by which he meant the disaster-ridden voyage that initially brought him to Japan.

Jan Joosten van Lodensteijn (1556?–1623?), a Dutch colleague of Adams' on their ill-fated voyage to Japan in the ship De Liefde, was also given similar privileges by Tokugawa Ieyasu. It appears Joosten became a samurai and was given a residence within Ieyasu's castle at Edo. Today, this area at the east exit of Tokyo Station is known as Yaesu (八重洲). Yaesu is a corruption of the Dutchman's Japanese name, Yayousu (耶楊子). Also in common with Adam's, Joostens was given a Red Seal Ship (朱印船) allowing him to trade between Japan and Indo-China. On a return journey from Batavia Joosten drowned after his ship ran aground.

During the Boshin War (1868–1869), French soldiers joined the forces of the Shogun against the Southern Daimyos favorable to the restoration of the Meiji Emperor. It is recorded that the French Navy officer Eugène Collache fought in samurai attire with his Japanese brothers-in-arms.

In the same war, the Prussian Edward Schnell served the Aizu domain as a military instructor and procurer of weapons. He was granted the Japanese name Hiramatsu Buhei (平松武兵衛), which inverted the characters of the daimyo's name Matsudaira. Hiramatsu (Schnell) was given the right to wear swords, as well as a residence in the castle town of Wakamatsu, a Japanese wife, and retainers. In many contemporary references, he is portrayed wearing a Japanese kimono, overcoat, and swords, with Western riding trousers and boots.

Weapons

- Japanese swords (samurai sword) are the weapons that have come to be synonymous with the samurai. Ancient Japanese swords from the Nara period (Chokutō) featured a straight blade, by the late 900s curved tachi appeared, followed by the uchigatana and ultimately the katana. Smaller commonly known companion swords are the wakizashi and the tantō.[34] Wearing a long sword (katana) or (tachi) together with a smaller sword such as a wakizashi or tantō became the symbol of the samurai, this combination of swords is referred to as a daishō (literally "big and small"). During the Edo period only samurai were allowed to wear a daisho.

- The yumi (longbow), reflected in the art of kyūjutsu (lit. the skill of the bow) was a major weapon of the Japanese military. Its usage declined with the introduction of the tanegashima (Japanese matchlock) during the Sengoku period, but the skill was still practiced at least for sport.[35] The yumi, an asymmetric composite bow made from bamboo, wood, rattan and leather, had an effective range of 50 or 100 meters (160 or 330 feet) if accuracy was not an issue. On foot, it was usually used behind a tate (手盾), a large, mobile wooden shield, but the yumi could also be used from horseback because of its asymmetric shape. The practice of shooting from horseback became a Shinto ceremony known as yabusame (流鏑馬).[36]

- Pole weapons including the yari and naginata were commonly used by the samurai. The yari (Japanese spear) displaced the naginata from the battlefield as personal bravery became less of a factor and battles became more organized around massed, inexpensive foot troops (ashigaru). A charge, mounted or dismounted, was also more effective when using a spear rather than a sword, as it offered better than even odds against a samurai using a sword. In the Battle of Shizugatake where Shibata Katsuie was defeated by Toyotomi Hideyoshi, then known as Hashiba Hideyoshi, seven samurai who came to be known as the "Seven Spears of Shizugatake" (賤ヶ岳七本槍) played a crucial role in the victory.[37]

- Tanegashima (Japanese matchlock) were introduced to Japan in the 1543 through Portuguese trade. Tanegashima were produced on a large scale by Japanese gunsmiths, enabling warlords to raise and train armies from masses of peasants. The new weapons were highly effective, their ease of use and deadly effectiveness led to the tanegashima becoming the weapon of choice over the yumi (bow). By the end of the 16th century, there were more firearms in Japan than in many European nations. Tanegashima—employed en masse, largely by ashigaru peasant foot troops—were responsible for a change in military tactics that eventually led to establishment of the Tokugawa shogunate (Edo period) and an end to civil war. Production of tanegashima declined sharply as there was no need for massive amounts of firearms. During the Edo period, tanegashima were stored away, and used mainly for hunting and target practice. Foreign intervention in the 1800s renewed interest in firearms—but the tanegashima was outdated by then, and various samurai factions purchased more modern firearms from European sources.

- Cannons became a common part of the samurai's armory in the 1570s. They often were mounted in castles or on ships, being used more as anti-personnel weapons than against castle walls or the like, though in the siege of Nagashino castle (1575) a cannon was used to good effect against an enemy siegetower. The first popular cannon in Japan were swivel-breech loaders nicknamed kunikuzushi or "province destroyers". Kunikuzushi weighed 264 lb (120 kg). and used 40 lb (18 kg). chambers, firing a small shot of 10 oz (280 g). The Arima clan of Kyushu used guns like this at the Battle of Okinawate against the Ryūzōji clan. By the time of the Osaka campaign (1614–1615), cannon technology had improved in Japan to the point where at Osaka, Ii Naotaka managed to fire an 18 lb (8.2 kg). shot into the castle's keep.

- Staff weapons of many shapes and sizes made from oak and other hard woods were also used by the samurai, commonly known ones include the bō, the jō, the hanbo, and the tanbo.

- Clubs and truncheons made of iron and/or wood, of all shapes and sizes were used by the samurai. Some like the jutte were one-handed weapons and others like the kanabo were large two-handed weapons.

- Chain weapons, various weapons using chains kusari were used during the samurai era, the kusarigama and Kusari-fundo are examples.

Armour

As far back as the seventh century Japanese warriors wore a form of lamellar armor, this armor eventually evolved into the armor worn by the samurai.[38] The first types of Japanese armors identified as samurai armor were known as yoroi. These early samurai armors were made from small individual scales known as kozane. The kozane were made from either iron or leather and were bound together into small strips, the strips were coated with lacquer to protect the kozane from water. A series of strips of kozane were then laced together with silk or leather lace and formed into a complete chest armor (dou or dō).[38]

In the 1500s a new type of armor started to become popular due to the advent of firearms, new fighting tactics and the need for additional protection. The kozane dou made from individual scales was replaced by plate armor. This new armor, which used iron plated dou (dō), was referred to as Tosei-gusoku, or modern armor.[39][40] Various other components of armor protected the samurai's body. The helmet kabuto was an important part of the samurai's armor. Samurai armor changed and developed as the methods of samurai warfare changed over the centuries.[41] The known last use of samurai armor occurring in 1877 during the satsuma rebellion.[42] As the last samurai rebellion was crushed, Japan modernized its defenses and turned to a national conscription army that used uniforms.[43]

Myth and reality

Most samurai were bound by a code of honor and were expected to set an example for those below them. A notable part of their code is seppuku (切腹 seppuku) or hara kiri, which allowed a disgraced samurai to regain his honor by passing into death, where samurai were still beholden to social rules. Whilst there are many romanticized characterizations of samurai behavior such as the writing of Bushido (武士道 Bushidō) in 1905, studies of Kobudo and traditional Budō indicate that the samurai were as practical on the battlefield as were any other warrior.

Despite the rampant romanticism of the 20th century, samurai could be disloyal and treacherous (e.g., Akechi Mitsuhide), cowardly, brave, or overly loyal (e.g., Kusunoki Masashige). Samurai were usually loyal to their immediate superiors, who in turn allied themselves with higher lords. These loyalties to the higher lords often shifted; for example, the high lords allied under Toyotomi Hideyoshi (豊臣秀吉) were served by loyal samurai, but the feudal lords under them could shift their support to Tokugawa, taking their samurai with them. There were, however, also notable instances where samurai would be disloyal to their lord or daimyo, when loyalty to the Emperor was seen to have supremacy.[44]

Popular culture

Jidaigeki (literally historical drama) has always been a staple program on Japanese movies and television. The programs typically feature a samurai. Samurai films and westerns share a number of similarities and the two have influenced each other over the years. One of Japan’s most renowned directors, Akira Kurosawa, greatly influenced the samurai aspect in western film-making. George Lucas’ Star Wars series incorporated many aspects from the Seven Samurai film. One example is that in the Japanese film, seven samurai warriors are hired by local farmers to protect their land from being overrun by bandits; In George Lucas’ Star Wars: A New Hope, a similar situation arises. Kurosawa was inspired by the works of director John Ford and in turn Kurosawa's works have been remade into westerns such as The Seven Samurai into The Magnificent Seven and Yojimbo into A Fistful of Dollars. There is also a 26 episode anime adaptation (Samurai 7) of The Seven Samurai. Along with film, literature containing samurai influences are seen as well.

Most common are historical works where the protagonist is either a samurai or former samurai (or another rank or position) who possesses considerable martial skill. Eiji Yoshikawa is one of the most famous Japanese historical novelists. His retellings of popular works, including Taiko, Musashi and Heike Tale, are popular among readers for their epic narratives and rich realism in depicting samurai and warrior culture. The samurai have also appeared frequently in Japanese comics (manga) and animation (anime). Samurai-like characters are not just restricted to historical settings and a number of works set in the modern age, and even the future, include characters who live, train and fight like samurai. Examples are Samurai Champloo, Requiem from the Darkness, Muramasa: The Demon Blade, and Afro Samurai. Some of these works have made their way to the west, where it has been increasing in popularity with America.

Just in the last two decades, samurai have become more popular in America. “Hyperbolizing the samurai in such a way that they appear as a whole to be a loyal body of master warriors provides international interest in certain characters due to admirable traits” (Moscardi, N.D.). Through various media, producers and writers have been capitalizing on the notion that Americans admire the samurai lifestyle. The animated series, Afro Samurai, became well-liked in American popular culture due to its blend of hack-and-slash animation and gritty urban music.

Created by Takashi Okazaki, Afro Samurai was initially a doujinshi, or manga series, which was then made into an animated series by Studio Gonzo. In 2007 the animated series debuted on American cable television on the Spike TV channel (Denison, 2010). The series was produced for American viewers which “embodies the trend... comparing hip-hop artists to samurai warriors, an image some rappers claim for themselves (Solomon, 2009). The storyline keeps in tone with the perception of a samurais finding vengeance against someone who has wronged him. Starring the voice of well known American actor Samuel L. Jackson, “Afro is the second-strongest fighter in a futuristic, yet, still feudal Japan and seeks revenge upon the gunman who killed his father” (King 2008). Due to its popularity, Afro Samurai was adopted into a full feature animated film and also became titles on gaming consoles such as the PlayStation 3 and Xbox. Not only has the samurai culture been adopted into animation and video games, it can also be seen in comic books.

American comic books have adopted the character type for stories of their own like the mutant-villain Silver Samurai of Marvel Comics. The design of this character preserves the samurai appearance; the villain is “Clad in traditional gleaming samurai armor and wielding an energy charged katana” (Buxton, 2013). Not only does the Silver Samurai make over 350 comic book appearances, the character is playable in several video games, such as Marvel Vs. Capcom 1 and 2. In 2013, the samurai villain was depicted in James Mangold’s film The Wolverine. Ten years before the Wolverine debuted, another film helped pave the way to ensure the samurai were made known to American cinema: A film released in 2003 titled The Last Samurai, starring Tom Cruise, is inspired by the samurai way of life. In the film, Cruise’s character finds himself deeply immersed in samurai culture. The character in the film, “Nathan Algren, is a fictional contrivance to make nineteenth-century Japanese history less foreign to American viewers”.(Ravina, 2010) After being captured by a group of samurai rebels, he becomes empathetic towards the cause they fight for. Taking place during the Meiji Period, Tom Cruise plays the role of US Army Captain Nathan Algren, who travels to Japan to train a rookie army in fighting off samurai rebel groups. Becoming a product of his environment, Algren joins the samurai clan in an attempt to rescue a captured samurai leader. “By the end of the film, he has clearly taken on many of the samurai traits, such as zen-like mastery of the sword, and a budding understanding of spirituality”. (Manion, 2006)

The television series Power Rangers Samurai (adapted from Samurai Sentai Shinkenger) is also inspired by the way of the Samurai.[45][46][47][48][49][50][51]

Famous samurai

- Akechi Mitsuhide

- Amakusa Shirō

- Date Masamune

- Hattori Hanzō

- Hōjō Ujimasa

- Honda Tadakatsu

- Kusunoki Masashige

- Minamoto no Yoshitsune

- Minamoto no Yoshiie

- Miyamoto Musashi

- Oda Nobunaga

- Saigō Takamori

- Saitō Hajime

- Sakamoto Ryōma

- Sanada Yukimura

- Sasaki Kojirō

- Shimazu Takahisa

- Shimazu Yoshihiro

- Takeda Shingen

- Tokugawa Ieyasu

- Tomoe Gozen

- Toyotomi Hideyoshi

- Uesugi Kenshin

- Ukon Takayama

- Yagyū Jūbei Mitsuyoshi

- Yagyū Munenori

- Yamamoto Tsunetomo

- Yamaoka Tesshū

See also

References

- ↑ Wilson, p. 17

- ↑ "Samurai (Japanese warrior)". Encyclopædia Britannica.

- 1 2 William Wayne Farris, Heavenly Warriors — The Evolution of Japan's Military, 500–1300, Harvard University Press, 1995. ISBN 0-674-38704-X

- ↑ A History of Japan, Vol. 3 and 4, George Samson, Tuttle Publishing, 2000.

- ↑ Wilson, p. 15

- ↑ Nagano Prefectural Museum of History (2005-03-01). "たたかう人びと". Comprehensive Database of Archaeological Site Reports in Japan. Retrieved 2016-09-02.

- ↑ Sharf 1993, p. 7.

- ↑ Sharf 1993, p. 12.

- ↑ Coleridge, p. 237

- ↑ Cleary, Thomas Training the Samurai Mind: A Bushido Sourcebook Shambhala (May, 2008) ISBN 1-59030-572-8

- ↑ Wilson, p. 38

- ↑ Carl Steenstrup, PhD Thesis, University of Copenhagen (1979)

- ↑ Wilson, p. 47

- ↑ Wilson, p. 62

- ↑ Wilson, p. 103

- ↑ Wilson, p. 95

- ↑ Wilson, p. 67

- ↑ Wilson, p, 131

- ↑ Stacey B. Day; Kiyoshi Inokuchi; Hagakure Kenkyūkai (1994). The wisdom of Hagakure: way of the Samurai of Saga domain. Hagakure Society. p. 61.

- ↑ Brooke Noel Moore; Kenneth Bruder (2001). Philosophy: the power of ideas. McGraw-Hill. p. 494. ISBN 978-0-7674-2011-2.

- ↑ Wilson, p. 122

- ↑ Wilson, p. 91

- ↑ Daisetz Teitarō Suzuki (1938). Zen and Japanese culture. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-01770-9.

- ↑ Daisetz Teitarō Suzuki (1938). Zen and Japanese culture. Princeton University Press. pp. 78–. ISBN 978-0-691-01770-9.

- ↑ H. Paul Varley (2000). Japanese culture. University of Hawaii Press. pp. 143–. ISBN 978-0-8248-2152-4.

- ↑ Coleridge, p. 100

- 1 2 Matsura, Yoshinori Fukuiken-shi 2 (Tokyo: Sanshusha, 1921)

- ↑ Philip J. Adler; Randall L. Pouwels (2007). World Civilizations: Since 1500. Cengage Learning. pp. 369–. ISBN 978-0-495-50262-3.

- 1 2 Wilson, p. 26

- ↑ Wilson

- ↑ R. H. P. Mason; John Godwin Caiger (15 November 1997). A history of Japan. Tuttle Publishing. pp. 152–. ISBN 978-0-8048-2097-4. Retrieved 9 April 2011.

- ↑ Wilson, p. 85

- ↑ Coleridge, p. 345

- ↑ Karl F. Friday (2004). Samurai, warfare and the state in early medieval Japan. Psychology Press. pp. 78–80. ISBN 978-0-415-32963-7. Retrieved 5 November 2011.

- ↑ Kathleen Haywood; Catherine Lewis (2006). Archery: steps to success. Human Kinetics. pp. 10–. ISBN 978-0-7360-5542-0. Retrieved 9 April 2011.

- ↑ Thomas Louis; Tommy Ito (5 August 2008). Samurai: The Code of the Warrior. Sterling Publishing Company, Inc. pp. 117–. ISBN 978-1-4027-6312-0. Retrieved 9 April 2011.

- ↑ Stephen Turnbull (11 April 2008). The Samurai Swordsman: Master of War. Tuttle Publishing. pp. 65–. ISBN 978-4-8053-0956-8. Retrieved 9 April 2011.

- 1 2 Stephen R. Turnbull (1996). The Samurai: a military history. Psychology Press. pp. 20–. ISBN 978-1-873410-38-7. Retrieved 9 April 2011.

- ↑ Clive Sinclaire (1 November 2004). Samurai: The Weapons and Spirit of the Japanese Warrior. Globe Pequot. pp. 32–. ISBN 978-1-59228-720-8. Retrieved 5 November 2011.

- ↑ William E. Deal (12 September 2007). Handbook to life in medieval and early modern Japan. Oxford University Press. pp. 171–. ISBN 978-0-19-533126-4. Retrieved 5 November 2011.

- ↑ Oscar Ratti; Adele Westbrook (1991). Secrets of the samurai: a survey of the martial arts of feudal Japan. Tuttle Publishing. pp. 186–. ISBN 978-0-8048-1684-7. Retrieved 9 April 2011.

- ↑ Clive Sinclaire (1 November 2004). Samurai: The Weapons and Spirit of the Japanese Warrior. Globe Pequot. pp. 58–. ISBN 978-1-59228-720-8. Retrieved 5 November 2011.

- ↑ The connoisseur's book of Japanese swords, Kōkan Nagayama, Kodansha International, 1998 p. 43

- ↑ Mark Ravina, The Last Samurai — The Life and Battles of Saigō Takamori, John Wiley & Sons, 2004.

- ↑ "Villains of The Wolverine: Silver Samurai and Viper". Den of Geek.

- ↑ Denison, R. (2010). Transcultural creativity in anime: Hybrid identities in the production, distribution, texts and fandom of Japanese anime. Creative Industries Journal, 3(3), 221–235. doi:10.1386/cij.3.3.221_1

- ↑ King, K. (2008). Afro Samurai. Booklist, 105(7), 44.

- ↑ Manion, Annie (August 2006). "Global Samurai". Japan Railway & Transport Review. Archived from the original on 2010-12-01. Retrieved 22 February 2014.

|archive-url=is malformed: timestamp (help) - ↑ Moscardi, N. (ND). The "Badass" Samurai in Japanese Pop Culture. Samurai Archives. Retrieved 24 February 2014, from http://Www.Samurai-archives.Com/bsj.Html

- ↑ Ravina, M. (2010). Fantasies of Valor: Legends of the Samurai in Japan and the United States. Asianetwork Exchange, 18(1), 80–99.

- ↑ "American, Japanese pop culture meld in 'Afro Samurai'". Los Angeles Times.

Bibliography

- Anderson, Patricia E. "Roles of Samurai Women: Social Norms and Inner Conflicts During Japan's Tokugawa Period, 1603-1868." New Views on Gender 15 (2015): 30-37. online

- Benesch, Oleg. Inventing the Way of the Samurai: Nationalism, Internationalism, and Bushido in Modern Japan. (Oxford UP, 2014). ISBN 0198706626, ISBN 9780198706625

- Clements, Jonathan. A Brief History of the Samurai (Running Press, 2010) ISBN 0-7624-3850-9

- Hubbard, Ben. The Samurai Warrior: The Golden Age of Japan's Elite Warriors 1560–1615 (Amber Books, 2015).

- Jaundrill, D. Colin. Samurai to Soldier: Remaking Military Service in Nineteenth-Century Japan (Cornell UP, 2016).

- Ogata, Ken. "End of the Samurai: A Study of Deinstitutionalization Processes." Academy of Management Proceedings Vol. 2015. No. 1.

- Sharf, Robert H. (August 1993). "The Zen of Japanese Nationalism". History of Religions. 33 (1): 1–43. Unknown parameter

|publishe=ignored (help) - Turnbull, Stephen. The Samurai: a military history (1996).

Primary sources

- Ansart, Olivier. "Lust, Commerce and Corruption: An Account of What I Have Seen and Heard by an Edo Samurai." Asian Studies Review 39.3 (2015): 529-530.

- Cummins, Antony, and Mieko Koizumi. The Lost Samurai School (North Atlantic Books, 2016) 17th century Samurai textbook on comnbat; heavily illustrated.

- Coleridge, Henry James. the Life and Letters of St. Francis Xavier. Forgotten Books. ISBN 978-1-4510-0048-1.

- Wilson, William Scott (1982). Ideals of the Samurai: Writings of Japanese Warriors. Kodansha. ISBN 0-89750-081-4.

External links

| Look up 侍 in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

| Look up samurai in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

Media related to Samurai at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Samurai at Wikimedia Commons- The Samurai Archives Japanese History page

- Samurai Swords and Samurai Culture

- History of the Samurai

- The Way of the Samurai-JAPAN:Memoirs of a Secret Empire

- Comprehensive Database of Archaeological Site Reports in Japan, Nara National Research Institute for Cultural Properties

-

"Samurai". New International Encyclopedia. 1905.

"Samurai". New International Encyclopedia. 1905.