Jarbidge Stage Robbery

| |

| Date | December 5, 1916 |

|---|---|

| Location | Jarbidge, Nevada, USA |

| Outcome | Bandits steal $4,000 |

| Deaths | 1 |

The Jarbidge Stage Robbery was the last stage robbery in the Old West. On December 5, 1916, the driver of a small two-horse mail wagon was ambushed as he was riding to the town of Jarbidge, Nevada. The driver was killed and $4,000 was stolen, however, three suspects were arrested shortly afterward, including a horse thief named Ben Kuhl. Kuhl would eventually become the first murderer in American history to be convicted and sent to prison by the use of palm print evidence. The stolen $4,000 was never recovered and is said to be buried somewhere in Jarbidge Canyon. According to author Ken Weinman, the Jarbidge Stage Robbery is one of the "best authenticated buried treasure stories in Nevada's long history."[1][2][3]

Background

In 1916, Jarbidge, Nevada was one of the state's most isolated communities, located within Jarbidge Canyon, along the Jarbidge River, about 100 miles north of Elko, Nevada and sixty-five miles south of Rogerson, Idaho. There was a Native American village nearby, called Owyhee, but it was just as remote as Jarbidge. The town was founded as a tent city in 1909, due to a gold rush, which brought about 1,500 people to the area. The winters there are very severe though and by the spring of 1910 the poupulation had reduced to just a few hundred. Ken Weinman wrote: "The miners had staked their claims on the snowdrifts covering the ground to a depth of as much as 18 feet, but when the snow melted in late spring, it exposed the exaggeration of the newspaper reports, and about 80 percent of the prospectors became disgusted and pulled up stakes and headed elsewhere."[2]

In many western states and territories, the turn of the century was no great change. Technological advancements were often slow in reaching isolated communities. Jarbidge was no exception. There was only one treacherous dirt road that led to the town and only one means of communication with the outside world, the United States Mail stage. Furthermore, in winter, twenty to thirty foot snow drifts could cut off the community for several weeks at a time. Automobiles had not yet made it to Jarbidge, so riding horses and driving wagons were still the main modes of transportation. Because Rogerson, Idaho was the closest railroad town to Jarbidge, the wagon driver, Fred Searcy, made round trips to and from, not only delivering mail, but also company payrolls for the local miners.[2]

Robbery

December 5, 1916 was payday for the miners. When Searcy failed to arrive in town at the expected time, a small group of men began to assemble at the post office, assuming that heavy snow was the cause of the delay. But, as the day went on, Searcy did not appear. Postmaster Scott Fleming asked a man named Frank Leonard to ride up to the top of Crippen Grade, a 2,000 foot decline in the road that led down to the canyon floor and the town. Leonard returned a few hours later, saying he could not find Searcy or the wagon. Fleming and the others were very concerned at that point. Over four feet of snow had fallen that day, which made the idea of sliding down the grade into the Jarbidge River seem like a real possibility. Fleming quickly formed a search party, but before leaving he telephoned a woman named Rose Dexter, who lived about a half mile north of Jarbidge, along the grade. According to Ken Weinman, Rose Dexter said that the stage had passed by her house earlier that day and that she waved to the driver. More interestingly, she said that the driver was "huddled up on his seat with his collar pulled up over his face to form some protection from the blinding snow." The search party quickly found the mail wagon, less than a quarter of a mile from the town's main business district. The stage was pulled over on the side of the road and hidden behind a patch of willow trees. Fred Searcy was found "slumped in his seat and almost covered with snow." An unopened mail pouch was also uncovered, but the second pouch, containing $4,000, was missing. Weinman says that at first the search party thought that Searcy had frozen to death in the extreme cold, but closer examination revealed that he had been shot in the head at a very close range. Powder burns in his hair and on his scalp were observed.[2]

Because the snow storm that was raging showed no sign of letting up, the search party returned to town with the intention of continuing the investigation of the area on the following morning. So, on the next day, the search party attempted to re-enact the crime using evidence found at the crime scene. According to Weinman, it was determined that the assailant must have hidden in the sagebrush along the road and jumped aboard the little wagon to kill Searcy and take control. However, the Nevada State Archivist, Guy Rocha, claims that Ben Kuhl later confessed to the murder and said that he killed Searcy over a dispute about how to split the money, alleging that Searcy was in on the crime. After the re-enactment, another patrol around the area was made and the searchers found both human and dog footprints in the snow. The tracks led down to the river and at its bank a blood stained shirt was found lying on the ground. While the search party was looking around, a stray dog that had been following the group began scratching at the dirt. A few seconds later, the dog unburied the second mail pouch. The bottom was cut open and $4,000 in bills and gold coins was missing. The clue was an important find, but the fact that the dog seemed to know right where it was buried raised suspicions that the animal tracks the group was following were made by the very same animal. The search party compared the dog's feet to the footprints in the snow and it was a perfect match. Then they wondered about who the dog would follow through the storm and they decided that Ben Kuhl was the one the dog was most attached to.[2][3]

Aftermath

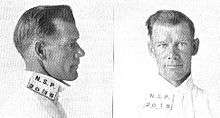

Kuhl and two of his associates, Ed Beck and William McGraw, were arrested at their cabin without any trouble and a .44 caliber ivory-handled revolver was found in their possession. According to Ken Weinman, Kuhl proclaimed his innocence, saying that he spent the night in the Jarbidge saloon. Witnesses confirmed that they saw Kuhl in the saloon, but because they could not say at what time their testimony was meaningless. Kuhl could have left the bar, committed the crime, and then returned in a relatively short amount of time. After his arrest, a background check revealed that Kuhl had a long criminal record. In 1903, he served four months in jail at Marysville, California for petty larceny and, at some other time, he was sent to the Oregon State Penitentiary for stealing horses. Furthermore, Kuhl had recently been released from jail on a $400 bond and had already been arrested in Jarbidge previously, for trespassing on private property. The trial was held in the Elko County Courthouse, District Judge Errol J. L. Taber presided over the case and District Attorney Edward P. Carville was the prosecutor. The evidence gathered by the search party was all circumstantial, but two forensic scientists from California linked a bloody palm print on an envelope to Kuhl. For this, Judge Taber sentenced Kuhl to death and gave him a choice as to how it should be done. Kuhl chose execution by firing squad, but the Nevada Board of Pardons later voted to commute his sentence to life in prison. Beck received a life sentence as well and McGraw turned state's evidence. All three were transferred to the Nevada State Prison together in October 1917.[2][3][4]

Kuhl spent almost twenty-eight years in prison before his release on May 16, 1945. At the time of his release, Kuhl had served more prison time in Nevada than anyone else in the state's history. Weinman says that the $4,000 was never recovered and that Kuhl never admitted to the crime or the existence of buried money, even though the police offered him time off his sentence if he revealed its location. Beck was paroled on November 24, 1923.[2][3]

Today the town of Jarbidge remains a small and isolated place with a population of less than 100. Many of the old buildings that stood during the time of the robbery are still intact, including the jail house in which Kuhl was held. In 1998, a plaque was placed in front of the jail, it reads:

Jarbidge Jail. Built after the town was removed from the U.S. Forest by a 1911 Presidential proclamation it replaced the constable's home or Forest Service cabin to restrain rowdy miners and hold suspects for arrival of a sheriff deputy. A colorful story tells of a burly miner frequently using the bunk to raise the roof to slip out and return to the saloon, climbing back in his cell before morning. Most noted prisoner was Ben Kuhl, who robbed the Rogerson-Jarbidge stage in December 1916, killing Fred Searcy the driver, the last mail stagecoach robbery in the U.S. and the first conviction based on a bloody palm print. It was last used about 1945. Dedicated June 13, 1998 by Lucinda Jane Saunders. Chapter 1881 E. Clampus Vitus.[5]

See also

Notes

- ↑ Roger Butterfield (1949). "Elko County: The Jarbridge Stage Robbery". Life Magazine. Time Inc. (April 18, 1949).

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 http://www.scribd.com/doc/48988148/America-s-Last-State-Robbery-in-1916-in-Jarbidge-Nevada

- 1 2 3 4 "Nevada State Library and Archives: Myth #95 - Staging a Robbery Without a Coach". Guy Rocha. November 2003. Retrieved June 26, 2012.

- ↑ "Howard Hickson's Histories: Case Number 606 Makes History: A Murder in Jarbidge, 1916". Howard Hickson. October 4, 1998. Retrieved June 26, 2012.

- ↑ "Reconnoitering in the Eastern Sierra Nevada & Great Basin by 4-Wheel-Drive: 4x4 Trails: Jarbidge, Nevada". August 24, 2010. Retrieved June 26, 2012.