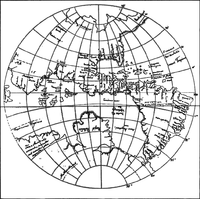

Johannes Schöner globe

The Johannes Schöner globes are a series of globes made by Johannes Schöner (1477–1547), the first being made in 1515. Schöner's globes are some of the oldest still in existence.[1] Some of them are said by some authors to show parts of the world that were not yet known to Europeans, such as the Magellan Strait and the Antarctic.[2]

Globes

The Johannes Schöner Globe (1515), a printed globe, was made in 1515.[3] Two exemplars survive, one at the Historisches Museum in Frankfurt and the other at the Herzogin Anna Amalia Bibliothek, at Weimar. There can be little doubt that Schöner was familiar with the globe made in Nuremberg by Martin Behaim in 1492.[4] A strait between the southern tip of America and the land to the south can be found on Schöner’s globe before its "official discovery" by Ferdinand Magellan in 1520. The strait is at 53 degrees south. The strait is shown at about 40 degrees south on the 1515 globe. Schöner accompanied his globe with an explanatory treatise, Luculentissima quaedam terrae totius descriptio (“A Most Lucid Description of All Lands”).[5]

The Johannes Schöner Globe (1520), a manuscript globe, was made in 1520. The globe shows the Antarctic continent which had not been explored at that date.[6] On Schöner’s 1515 and 1520 globes, AMERICA is shown as an island, as he explained in the Luculentissima:

America, the fourth part of the world, and the other islands belonging to it. In this way it may be known that the Earth is in four parts and that the first three parts are continents, that is, terra firma, but that the fourth is an island, for it is seen to be surrounded everywhere by the seas”.[7]

This is drawn from the Cosmographiae Introductio of Martin Waldseemüller, which said:

Hitherto [the whole earth] has been divided into three parts, Europe, Africa, and Asia… Now, these parts of the earth have been more extensively explored and a fourth part has been discovered by Amerigo Vespucci... Thus the earth is now known to be divided into four parts. The first three parts are continents, while the fourth is an island, inasmuch as it is found to be surrounded on all sides by the seas.[8]

The Johannes Schöner Globe (1523), a printed globe, was made in 1523. It was considered to have been lost until identified by George Nunn in 1927.[9]

. The Johannes Schöner's printed Weimar Globe (1533) was made in 1533. It shows North America as part of Asia and also shows Antarctica. He wrote a treatise. the Opusculum Geographicum, to accompany this globe.[10] In this, he described the cosmographic approach he had used in constructing his globe: “I had to hand marine charts drawn in excellent characters, and news of great price and value which I located to concord, as much as possible, with astronomical positions”. (Opusc. Geogr., Pt.I, cap.ix).[11]

On Schoener’s 1523 and 1530 globes, AMERICA is shown as a part of Asia, as he explained in the Opusculum Geographicum:

After Ptolemy, many regions to the east beyond 180 degrees were discovered by Marco Polo the Venetian, and others, but now having been discovered by the Genoese Columbus and Americo Vespucci reaching only the coastal parts of those lands from Spain across the Western Ocean, were considered by them to be an island which they called America, the fourth part of the globe. But by the most recent voyages made in the year 1519 after Christ by Magellan leading ships of the Invincible Divine Charles etc. to the Moluccas Islands, which others call Maluquas, situated in the Far East, they have found that land to be the continent of Upper India, which is a part of Asia.[12]

The globe of 1515 owes an obvious debt to the Waldseemüller map of 1507, which in turn was derived from the globe constructed in Nuremberg in 1492 by Martin Behaim. Schöner’s 1515 globe follows these in representing India Superior (eastern Asia, called India superior sive orientalis in the Luculentissima) as extending to around longitude 270° East. Westward from Spain, the discoveries of Christopher Columbus, Amerigo Vespucci and the other Spanish and Portuguese navigators are represented as a long, narrow strip of lands stretching from about latitude 50° North to about 40° South. The western coasts of these lands, America in the south and Parias in the north, are labelled Terra ultra incognita ("Land beyond unknown") and Vlterius incognita terra ("Land further beyond unknown"), indicating it was unknown how far westward they extended. The sea to the west of these lands is labelled Oceanus orientalis indianus (Eastern Indian Ocean), in accordance with the conclusion reached by Columbus after his third voyage of 1496-1498, when he encountered the South American mainland, which he called a Nuevo Mundo and identified with Marco Polo’s “greatest island in the world”, Java Major, lying south west of the India Superior province of Ciamba (Champa). Reflecting this concept, Schöner explained in another of his writings, the Opusculum Geographicum (cap.xx): “the Genoese Columbus and Americo Vespucci reaching only the coastal parts of those lands from Spain across the Western Ocean, considered them to be an island which they called America”. Or, as Nicolaus Copernicus put it in De Revolutionibus (lib.I, cap.iii):

Ptolemy extended the habitable area halfway around the world, leaving beyond it unknown land, where the moderns have added Cathay and very extensive regions as far as 60 degrees of longitude, so that now a greater longitude of land is inhabited than is left for the Ocean. Moreover, to this should be added the great islands discovered in our time under the Princes of Spain and Portugal, especially America, named after the captain of the ship who discovered it and thought because of its yet hidden size to be another world, besides many other islands heretofore unknown, which we do not wonder to regard as being the Antipodes or Antichthones.

Where Schöner departs most conspicuously from Waldseemüller is in his globe’s depiction of an Antarctic continent, called by him Brasilie Regio. His continent is based, however tenuously, on the report of an actual voyage: that of the Portuguese merchants Nuno Manuel and Cristóvão de Haro to the River Plate, and related in the Newe Zeytung auss Presillg Landt (“New Tidings from the Land of Brazil”) published in Augsburg in 1514. The Zeytung described the Portuguese voyagers passing through a strait between the southernmost point of America, or Brazil, and a land to the south west, referred to as vndtere Presill or Brasilia inferior. This supposed “strait” was in fact the Rio de la Plata (and/or eventually the San Matias Gulf). By “vndtere Presill”, the Zeytung meant that part of Brazil in the lower latitudes, but Schöner mistook it to mean the land on the southern side of the “strait”, in higher latitudes, and so gave to it the opposite meaning. On this slender foundation he constructed his circum-Antarctic continent to which, for reasons that he does not explain he gave an annular, or ring shape. In the Luculentissima he explained:

The Portuguese, thus, sailed around this region, the Brasilie Regio, and discovered the passage very similar to that of our Europe (where we reside) and situated laterally between east and west. From one side the land on the other is visible; and the cape of this region about 60 miles away, much as if one were sailing eastward through the Straits of Gibraltar or Seville and Barbary or Morocco in Africa, as our Globe shows toward the Antarctic Pole. Further, the distance is only moderate from this Region of Brazil to Malacca, where St. Thomas was crowned with martyrdom.[13]

On this scrap of information, united with the concept of the Antipodes inherited from Graeco-Roman antiquity, Schöner constructed his representation of the southern continent. His strait served as inspiration for Ferdinand Magellan’s expedition to reach the Moluccas by a westward route. He took Magellan’s discovery of Tierra del Fuego in 1520 as further confirmation of its existence, and on his globes of 1523 and 1533 he described it as TERRA AVSTRALIS RECENTER INVENTA SED NONDUM PLENE COGNITA(“Terra Australis, recently discovered but not yet fully known”). It was taken up by his followers, the French cosmographer Oronce Fine in his world map of 1531, and the Flemish cartographers Gerard Mercator in 1538 and Abraham Ortelius in 1570. Schöner’s concepts influenced the Dieppe maps makers, notably in their representation of Jave la Grande. Subsequent generations of map-makers and geographic theorists continued to elaborate the image of a vast and wealthy Terra Australis to tempt the cupidity of merchants and statesmen.

See also

- Johannes Schöner

- Erdapfel

- Hunt–Lenox Globe

- Globus Jagellonicus

- Ancient world maps

- World map

- Timeline of pre-Columbian trans-oceanic contact

- Pre-Columbian trans-oceanic contact

- Martin Waldseemüller

- Jave la Grande

- Guillaume Postel, a French polymath

References

- ↑ Norbert Holst, Mundus, Mirabilia, Mentalität: Weltbild und Quellen des Kartographen Johannes Schöner: eine Spurensuche, Frankfurt/Oder, Scripvaz, 1999. ISBN 3-931278-10-7

- ↑ Fricker, Karl (1900). The Antarctic Regions. S. Sonnenschein & Company, limited.

- ↑ Chet Van Duzer, Johann Schöner’s Globe of 1515: Transcription and Study, American Philosophical Society, Philadelphia, PA, 2010, ISBN 978-1-60618-005-1

- ↑ Franz Wawrik, “The Johann Schöner Collection of Cartographical Works in the Austrian National Library”, in Congresso internazionale di Storia della Cartografia, Imago et Mensura Mundi: Atti del IX Congresso, Roma, Istituto della Enciclopedia Italiana, 1985, Vol.I, pp.297-301, p. 298.

- ↑ Luculentissima quaedam terrae totius descriptio, 1515; published in facsimile on the Web by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG)at:

- ↑ Friedrich Wilhelm Ghillany, Geschichte des Seefahrers Ritter Martin Behaim, Nürnberg, Bauer und Raspe, J. Merz, 1853.

- ↑ Johannes Schoner, Luculentissima quaedam terrae totius descriptio, Nuremberg, 1515, Tract I, cap.ix, f.2: America: quarta orbis parte cum aliis nouis insulis Oceano occidentali inventus.

- ↑ Martin Waldseemüller, Cosmographiae Introductio, Chapter IX, “Of Certain Elements of Cosmography“.

- ↑ George E. Nunn, "The Lost Globe Gores of Johann Schöner, 1523-1524", The Geographical Review, vol.17, no.3, July 1927, pp.476-480.

- ↑ Ioannis Schoneri ... Opusculum geographicum ex diversorum libris ac cartis ... collectum, 1533

- ↑ Quoted in Lucien Gallois, Les Géographes allemands de la Renaissance (Paris, Leroux, 1890, repr. Amsterdam, Meridian, 1963)p.93.

- ↑ Johannes Schoener, Opusculum Geographicum, Norimberga, [1533], Pars II, cap.xx.

- ↑ Luculentissima, f.61v.

External links

- The Johann Schönner globe of the world of 1520 at Nito Verdera's site.

- Luculentissima quaedam terrae totius descriptio: cum multis vtilissimis cosmographiæ iniciis. Noribergæ, Impressum im excusoria officina I. Stuchssen, 1515. From the Rare Book and Special Collections Division at the Library of Congress