Portuguese discoveries

Portuguese discoveries (Portuguese: Descobrimentos portugueses) are the numerous territories and maritime routes discovered by the Portuguese as a result of their intensive maritime exploration during the 15th and 16th centuries. Portuguese sailors were at the vanguard of European overseas exploration, discovering and mapping the coasts of Africa, Canada, Asia and Brazil, in what became known as the Age of Discovery. Methodical expeditions started in 1419 along West Africa's coast under the sponsorship of prince Henry the Navigator, with Bartolomeu Dias reaching the Cape of Good Hope and entering the Indian Ocean in 1488. Ten years later, in 1498, Vasco da Gama led the first fleet around Africa to India, arriving in Calicut and starting a maritime route from Portugal to India. Portuguese explorations then proceeded to southeast Asia, where they reached Japan in 1542, forty-four years after their first arrival in India.[1] In 1500, the Portuguese nobleman Pedro Álvares Cabral became the first European to discover Brazil.[2]

Origins

In 1139 the Kingdom of Portugal achieved independence from León, having doubled its area with the Reconquista under Afonso Henriques.

In 1297 king Denis of Portugal took personal interest in the development of exports, having organized the export of surplus production to European countries. On May 10, 1293 he instituted a maritime insurance fund for Portuguese traders living in the County of Flanders, which were to pay certain sums according to tonnage, accrued to them when necessary. Wine and dried fruits from Algarve were sold in Flanders and England, salt from Setúbal and Aveiro was a profitable export to northern Europe, and leather and kermes, a scarlet dye, were also exported. Portuguese imported armors and munitions, fine clothes and several manufactured products from Flanders and Italy.[3]

In 1317 king Denis made an agreement with Genoese merchant sailor Manuel Pessanha (Pesagno), appointing him first Admiral with trade privileges with his homeland in return for twenty war ships and crews, with the goal of defending the country against Muslim pirate raids, thus laying the basis for the Portuguese Navy and establishment of a Genoese merchant community in Portugal.[4] Forced to reduce their activities in the Black Sea, the Republic of Genoa had turned to north African trade of wheat, olive oil (valued also as energy source) and a search for gold – navigating also into the ports of Bruges (Flanders) and England. Genoese and Florentine communities established since then in Portugal, who profited from the enterprise and financial experience of these rivals of the Republic of Venice.

In the second half of the fourteenth century outbreaks of bubonic plague led to severe depopulation: the economy was extremely localized in a few towns, and migration from the country led to land being abandoned to agriculture and resulting in village unemployment rise. Only the sea offered alternatives, with most people settling in fishing and trading coastal areas.[5] Between 1325–1357 Afonso IV of Portugal granted public funding to raise a proper commercial fleet and ordered the first maritime explorations, with the help of Genoese, under command of admiral Manuel Pessanha. In 1341 the Canary Islands, already known to Genoese, were officially discovered under the patronage of the Portuguese king, but in 1344 Castile disputed them, further propelling the Portuguese navy efforts.[6]

Atlantic exploration (1415–1488)

In 1415, Ceuta was occupied by the Portuguese aiming to control navigation of the African coast, moved by expanding Christianity with the avail of the Pope and a desire of the unemployed nobility for epic acts of war after the reconquista. Young prince Henry the Navigator was there and became aware of profit possibilities in the Saharan trade routes. Governor of the rich Order of Christ since 1420 and holding valuable monopolies on resources in Algarve, he invested in sponsoring voyages down the coast of Mauritania, gathering a group of merchants, shipowners, stakeholders and participants interested in the sea lanes. Later his brother Prince Pedro, granted him a "Royal Flush" of all profits from trading within the areas discovered. Soon the Atlantic islands of Madeira (1420) and Azores (1427) were reached. There wheat and later sugarcane were cultivated, like in Algarve, by the Genoese, becoming profitable activities. This helped them become more wealthy.

Henry the Navigator took the lead role in encouraging Portuguese maritime exploration until his death in 1460.[7] At the time, Europeans did not know what lay beyond Cape Bojador on the African coast. Henry wished to know how far the Muslim territories in Africa extended, and whether it was possible to reach Asia by sea, both to reach the source of the lucrative spice trade and perhaps to join forces with the long-lost Christian kingdom of Prester John that was rumoured to exist somewhere in the "Indies".[8][9]

In 1419 two of Henry's captains, João Gonçalves Zarco and Tristão Vaz Teixeira were driven by a storm to Madeira, an uninhabited island off the coast of Africa which had probably been known to Europeans since the 14th century. In 1420 Zarco and Teixeira returned with Bartolomeu Perestrelo and began Portuguese settlement of the islands. A Portuguese attempt to capture Grand Canary, one of the nearby Canary Islands, which had been partially settled by Spaniards in 1402 was unsuccessful and met with protestations from Castile.[10] Although the exact details are uncertain, cartographic evidence suggests the Azores were probably discovered in 1427 by Portuguese ships sailing under Henry's direction, and settled in 1432, suggesting that the Portuguese were able to navigate at least 745 miles (1,200 km) from the Portuguese coast.[11]

At around the same time as the unsuccessful attack on the Canary Islands, the Portuguese began to explore the North African coast. Sailors feared what lay beyond Cape Bojador, and whether it was possible to return once it was passed. In 1434 one of Prince Henry's captains, Gil Eanes, passed this obstacle. Once this psychological barrier had been crossed, it became easier to probe further along the coast.[12] Westward exploration continued over the same period: Diogo Silves discovered the Azores island of Santa Maria in 1427 and in the following years Portuguese discovered and settled the rest of the Azores. Within two decades of exploration, Portuguese ships bypassed the Sahara.

Henry suffered a serious setback in 1437 after the failure of an expedition to capture Tangier, having encouraged his brother, King Edward, to mount an overland attack from Ceuta. The Portuguese army was defeated and only escaped destruction by surrendering Prince Ferdinand, the king's youngest brother.[13] After the defeat at Tangier, Henry retired to Sagres on the southern tip of Portugal where he continued to direct Portuguese exploration until his death in 1460.

In 1443 Prince Pedro, Henry's brother, granted him the monopoly of navigation, war and trade in the lands south of Cape Bojador. Later this monopoly would be enforced by the Papal bulls Dum Diversas (1452) and Romanus Pontifex (1455), granting Portugal the trade monopoly for the newly discovered countries,[14] laying the basis for the Portuguese empire.

A major advance which accelerated this project was the introduction of the caravel in the mid-15th century, a ship that could be sailed closer to the wind than any other in operation in Europe at the time.[15] Using this new maritime technology, Portuguese navigators reached ever more southerly latitudes, advancing at an average rate of one degree a year.[16] Senegal and Cape Verde Peninsula were reached in 1445. The first feitoria trade post overseas was established then under Henry's directions, in 1445 on the island of Arguin off the coast of Mauritania, to attract Muslim traders and monopolize the business in the routes traveled in North Africa, starting the chain of Portuguese feitorias along the coast. In 1446, Álvaro Fernandes pushed on almost as far as present-day Sierra Leone and the Gulf of Guinea was reached in the 1460s.

Exploration after Prince Henry

As a result of the first meager returns of the African explorations, in 1469 king Afonso V granted the monopoly of trade in part of the Gulf of Guinea to merchant Fernão Gomes, for an annual payment of 200,000 reals. Gomes was also required to explore 100 leagues (480 km) of the coast each year for five years.[17] He employed explorers João de Santarém, Pedro Escobar, Lopo Gonçalves, Fernão do Pó, and Pedro de Sintra, and exceeded the requirement. Under his sponsorship, Portuguese explorers crossed the Equator into the Southern Hemisphere and found the islands of the Gulf of Guinea, including São Tomé and Príncipe.[18]

In 1471, Gomes' explorerers reached Elmina on the Gold Coast (present day Ghana), and discovered a thriving gold trade between the natives and visiting Arab and Berber traders. Gomes established his own trading post there, which became known as “A Mina” ("The Mine"). Trade between Elmina and Portugal grew in the next decade.[19] In 1481, the recently crowned João II decided to build São Jorge da Mina fort (Elmina Castle) and factory to protect this trade, which was then held again as a royal monopoly.

In 1482, Diogo Cão discovered the Congo River. In 1486, Cão continued to Cape Cross, in present-day Namibia, near the Tropic of Capricorn.

In 1488, Bartolomeu Dias rounded the Cape of Good Hope on the southern tip of Africa, disproving the view that had existed since Ptolemy that the Indian Ocean was separate from the Atlantic. Also at this time, Pêro da Covilhã reached India via Egypt and Yemen, and visited Madagascar. He recommended further exploration of the southern route.[20]

As the Portuguese explored the coastlines of Africa, they left behind a series of padrões, stone crosses enscribed with the Portuguese coat of arms marking their claims,[21] and built forts and trading posts. From these bases, the Portuguese engaged profitably in the slave and gold trades. Portugal enjoyed a virtual monopoly of the Atlantic slave trade for over a century, exporting around 800 slaves annually. Most were brought to the Portuguese capital Lisbon, where it is estimated black Africans came to constitute 10 per cent of the population.[22]

Tordesillas division of the world (1492)

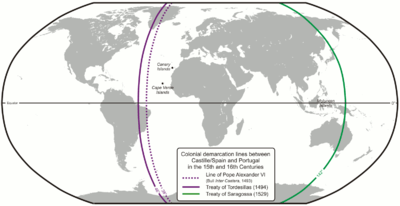

In 1492 Christopher Columbus's discovery for Spain of the New World, which he believed to be Asia, led to disputes between the Spanish and Portuguese. These were eventually settled by the Treaty of Tordesillas in 1494 which divided the world outside of Europe in an exclusive duopoly between the Portuguese and the Spanish, along a north-south meridian 370 leagues, or 970 miles (1,560 km), west of the Cape Verde islands. However, as it was not possible at the time to correctly measure longitude, the exact boundary was disputed by the two countries until 1777.[23]

The completion of these negotiations with Spain is one of several reasons proposed by historians for why it took nine years for the Portuguese to follow up on Dias's voyage to the Cape of Good Hope, though it has also been speculated that other voyages were in fact taking place in secret during this time.[24][25] Whether or not this was the case, the long-standing Portuguese goal of finding a sea route to Asia was finally achieved in a ground-breaking voyage commanded by Vasco da Gama.

Reaching India and Brazil (1497–1500)

The squadron of Vasco da Gama left Portugal in 1497, rounded the Cape and continued along the coast of East Africa, where a local pilot was brought on board who guided them across the Indian Ocean, reaching Calicut in western India in May 1498.[26] The second voyage to India was dispatched in 1500 under Pedro Álvares Cabral. While following the same south-westerly route as Gama across the Atlantic Ocean, Cabral made landfall on the Brazilian coast. This was probably an accidental discovery, but it has been speculated that the Portuguese secretly knew of Brazil's existence and that it lay on their side of the Tordesillas line.[27] Cabral recommended to the Portuguese King that the land be settled, and two follow up voyages were sent in 1501 and 1503. The land was found to be abundant in pau-brasil, or brazilwood, from which it later inherited its name, but the failure to find gold or silver meant that for the time being Portuguese efforts were concentrated on India.[28]

On 8 July 1497 the fleet, consisting of four ships and a crew of 170 men, left Lisbon The travel led by Vasco da Gama to Calicut was the starting point for deployment of Portuguese in the African east coast and in the Indian Ocean.[29] The first contact occurred on 20 May 1498. After some conflict, he got an ambiguous letter for trade with the Zamorin of Calicut, leaving there some men to establish a trading post. Since then explorations lost the private nature, taking place under the exclusive of the Portuguese Crown. Shortly after, was established in Lisbon the Casa da Índia to administer the royal monopoly of navigation and trade.

Indian Ocean explorations (1497–1542)

The aim of Portugal in the Indian Ocean was to ensure the monopoly of the spice trade. Taking advantage of the rivalries that pitted Hindus against Muslims, the Portuguese established several forts and trading posts between 1500 and 1510. In East Africa, small Islamic states along the coast of Mozambique, Kilwa, Brava, Sofala and Mombasa were destroyed, or became either subjects or allies of Portugal. Pêro da Covilhã had reached Ethiopia, traveling secretly overland, as early as 1490;[30] a diplomatic mission reached the ruler of that nation on October 19, 1520.

In 1500 the second fleet to India who came to discover Brazil explored the East African coast, where Diogo Dias discovered the island that he named St. Lawrence, later known as Madagascar. This fleet, commanded by Pedro Álvares Cabral, arrived at Calicut in September, where the first trade agreement in India was signed. For a short time a Portuguese factory was installed there, but was attacked by Muslims on December 16 and several Portuguese, including the scribe Pêro Vaz de Caminha, died. After bombarding Calicut as a retaliation, Cabral went to rival Kochi.

Profiting from the rivalry between the Maharaja of Kochi and the Zamorin of Calicut, the Portuguese were well received and seen as allies, getting a permit to build a fort (Fort Manuel) and a trading post that were the first European settlement in India. There in 1503 they built the St. Francis Church.[31][32] In 1502 Vasco da Gama took the island of Kilwa on the coast of Tanzania, where in 1505 the first fort of Portuguese East Africa was built to protect ships from the East Indian trade.

In 1505 king Manuel I of Portugal appointed Francisco de Almeida first Viceroy of Portuguese India for a three-year period, starting the Portuguese government in the east, headquartered at Kochi. That year the Portuguese conquered Kannur where they founded St. Angelo Fort. Lourenço de Almeida arrived in Ceylon (modern Sri Lanka), where he discovered the source of cinnamon. Finding it divided into seven rival kingdoms, he established a defense pact with the kingdom of Kotte and extended the control in coastal areas, where in 1517 was founded the fortress of Colombo.[33]

In 1506 a Portuguese fleet under the command of Tristão da Cunha and Afonso de Albuquerque, conquered Socotra at the entrance of the Red Sea and Muscat in 1507, having failed to conquer Ormuz, following a strategy intended to close the entrances to the Indian Ocean. That same year were built fortresses in the Island of Mozambique and Mombasa on the Kenyan coast. Madagascar was partly explored by Tristão da Cunha and in the same year Mauritius was discovered.

In 1509, the Portuguese won the sea Battle of Diu against the combined forces of the Ottoman Sultan Beyazid II, Sultan of Gujarat, Mamlûk Sultan of Cairo, Samoothiri Raja of Kozhikode, Venetian Republic, and Ragusan Republic (Dubrovnik). The Portuguese victory was critical for its strategy of control of the Indian Sea: Turks and Egyptians withdraw their navies from India, leaving the seas to the Portuguese, setting its trade dominance for almost a century, and greatly assisting the growth of the Portuguese Empire. It marked also the beginning of the European colonial dominance in the Asia. A second Battle of Diu in 1538 finally ended Ottoman ambitions in India and confirmed Portuguese hegemony in the Indian Ocean.

Under the government of Albuquerque, Goa was taken from the Bijapur sultanate in 1510 with the help of Hindu privateer Timoji. Coveted for being the best port in the region, mainly for the commerce of Arabian horses for the Deccan sultanates, it allowed to move on from the initial guest stay in Cochin. Despite constant attacks, Goa became the seat of the Portuguese government, under the name of Estado da India (State of India), with the conquest triggering compliance of neighbour kingdoms: Gujarat and Calicut sent embassies, offering alliances and grants to fortify. Albuquerque began that year in Goa the first Portuguese mint in India, taking the opportunity to announce the achievement.[34][35]

Southeast Asia expeditions

In April 1511 Albuquerque sailed to Malacca in Malaysia,[36] the most important eastern point in the trade network, where Malay met Gujarati, Chinese, Japanese, Javanese, Bengali, Persian and Arabic traders, described by Tomé Pires as invaluable. The port of Malacca became then the strategic base for Portuguese trade expansion with China and Southeast Asia, under the Portuguese rule in India with its capital at Goa. To defend the city a strong fort was erected, called the "A Famosa", where one of its gate still remains today. Knowing of Siamese ambitions over Malacca, Albuquerque sent immediately Duarte Fernandes on a diplomatic mission to the kingdom of Siam (modern Thailand), where he was the first European to arrive, establishing amicable relations between both kingdoms.[37] In November that year, getting to know the location of the so-called "Spice Islands" in the Moluccas, he sent an expedition led by António de Abreu to find them, arriving in early 1512. Abreu went by Ambon while deputy commander Francisco Serrão came forward to Ternate, were a Portuguese fort was allowed. That same year, in Indonesia, the Portuguese took Makassar, reaching Timor in 1514. Departing from Malacca, Jorge Álvares came to southern China in 1513. This visit was followed the arrival in Guangzhou, where trade was established. Later a trade post at Macau would be established.

The Portuguese empire expanded into the Persian Gulf as Portugal contested control of the spice trade with the Ottoman Empire. In 1515, Afonso de Albuquerque conquered the Huwala state of Hormuz at the head of the Persian Gulf, establishing it as a vassal state. Aden, however, resisted Albuquerque's expedition in that same year, and another attempt by Albuquerque's successor Lopo Soares de Albergaria in 1516, before capturing Bahrain in 1521, when a force led by António Correia defeated the Jabrid King, Muqrin ibn Zamil.[38] In a shifting series of alliances, the Portuguese dominated much of the southern Persian Gulf for the next hundred years. With the regular maritime route linking Lisbon to Goa since 1497, the island of Mozambique become a strategic port, and there was built Fort São Sebastião and an hospital. In the Azores, the Islands Armada protected the ships en route to Lisbon.

In 1521, Cristóvão de Mendonça discovers Australia.

In 1525, after Fernão de Magalhães's expedition (1519–1522), Spain under Charles V sent an expedition to colonize the Moluccas islands, claiming that they were in his zone of the Treaty of Tordesillas, since there was not a set limit to the east. García Jofre de Loaísa expedition reached the Moluccas, docking at Tidore. The conflict with the Portuguese already established in nearby Ternate was inevitable, starting nearly a decade of skirmishes. An agreement was reached only with the Treaty of Zaragoza (1529), attributing the Moluccas to Portugal and the Philippines to Spain.

In 1530, John III organized the colonization of Brazil around 15 capitanias hereditárias ("hereditary captainships"), that were given to anyone who wanted to administer and explore them, to overcome the need to defend the territory, since an expedition under the command of Gonçalo Coelho in 1503, found the French making incursions on the land. That same year, there was a new expedition from Martim Afonso de Sousa with orders to patrol the whole Brazilian coast, banish the French, and create the first colonial towns: São Vicente on the coast, and São Paulo on the border of the altiplane. From the 15 original captainships, only two, Pernambuco and São Vicente, prospered. With permanent settlement came the establishment of the sugar cane industry and its intensive labor demands which were met with Native American and later African slaves.

In 1534 Gujarat was occupied by the Mughals and the Sultan Bahadur Shah of Gujarat was forced to sign the Treaty of Bassein (1534) with the Portuguese, establishing an alliance to regain the country, giving in exchange Daman, Diu, Mumbai and Bassein.[39] In 1538 the fortress of Diu is again surrounded by Ottoman ships. Another siege failed in 1547 putting an end to the Ottoman ambitions, confirming the Portuguese hegemony.

In 1542 Jesuit missionary Francis Xavier arrived in Goa at the service of king John III of Portugal, in charge of an Apostolic Nunciature. At the same time Francisco Zeimoto and other traders arrived in Japan for the first time. According to Fernão Mendes Pinto, who claimed to be in this journey, they arrived at Tanegashima, where the locals were impressed by firearms, which would be immediately made by the Japanese on a large scale.[40] In 1557 the Chinese authorities allowed the Portuguese to settle in Macau through an annual payment, creating a warehouse in the triangular trade between China, Japan and Europe. In 1570 the Portuguese bought a Japanese port where they founded the city of Nagasaki,[41] thus creating a trading center for many years was the port from Japan to the world.

Portugal established trading ports at far-flung locations like Goa, Ormuz, Malacca, Kochi, the Maluku Islands, Macau, and Nagasaki. Guarding its trade from both European and Asian competitors, Portugal dominated not only the trade between Asia and Europe, but also much of the trade between different regions of Asia, such as India, Indonesia, China, and Japan. Jesuit missionaries, such as the Basque Francis Xavier, followed the Portuguese to spread Roman Catholic Christianity to Asia with mixed success.

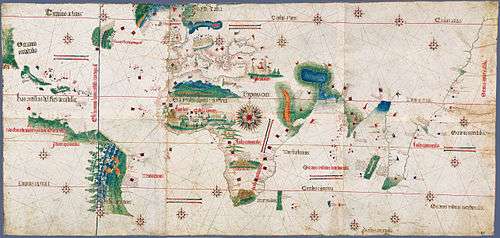

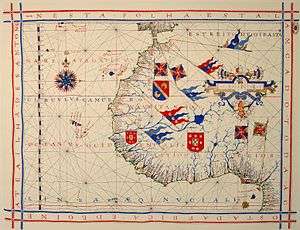

Map of Portuguese discoveries and explorations (1415–1543)

Portuguese nautical science

The successive expeditions and experience of the pilots led to a fairly rapid evolution of Portuguese nautical science, creating an elite of astronomers, navigators, mathematicians and cartographers, among them stood Pedro Nunes with studies on how to determine the latitudes by the stars and João de Castro.

Ships

Until the 15th century, the Portuguese were limited to cabotage navigation using barques and barinels (ancient cargo vessels used in the Mediterranean). These boats were small and fragile, with only one mast with a fixed quadrangular sail and did not have the capabilities to overcome the navigational difficulties associated with Southward oceanic exploration, as the strong winds, shoals and strong ocean currents easily overwhelmed their abilities. They are associated with the earliest discoveries, such as the Madeira Islands, the Azores, the Canaries, and to the early exploration of the north west African coast as far south as Arguim in the current Mauritania.

The ship that truly launched the first phase of the Portuguese discoveries along the African coast was the caravel, a development based on existing fishing boats. They were agile and easier to navigate, with a tonnage of 50 to 160 tons and 1 to 3 masts, with lateen triangular sails allowing luffing. The caravel benefited from a greater capacity to tack. The limited capacity for cargo and crew were their main drawbacks, but have not hindered its success. Among the famous caravels are Berrio and Anunciação.

With the start of long oceanic sailing also large ships developed. "Nau" was the Portuguese archaic synonym for any large ship, primarily merchant ships. Due to the piracy that plagued the coasts, they began to be used in the navy and were provided with canon windows, which led to the classification of "naus" according to the power of its artillery. They were also adapted to the increasing maritime trade: from 200 tons capacity in the 15th century to 500, they become impressive in the 16th century, having usually two decks, stern castles fore and aft, two to four masts with overlapping sails. In India travels in the sixteenth century there were also used carracks, large merchant ships with a high edge and three masts with square sails, that reached 2000 tons.

Celestial navigation

In the thirteenth century celestial navigation was already known, guided by the sun position. For celestial navigation the Portuguese, like other Europeans, used Arab navigation tools, like the astrolabe and quadrant, which they made easier and simpler. They also created the cross-staff, or cane of Jacob, for measuring at sea the height of the sun and other stars. The Southern Cross become a reference upon arrival at the Southern hemisphere by João de Santarém and Pedro Escobar in 1471, starting the celestial navigation on this constellation. But the results varied throughout the year, which required corrections.

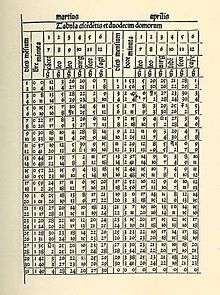

To this the Portuguese used the astronomical tables (Ephemeris), precious tools for oceanic navigation, which have experienced a remarkable diffusion in the fifteenth century. These tables revolutionized navigation, allowing to calculate latitude. The tables of the Almanach Perpetuum, by astronomer Abraham Zacuto, published in Leiria in 1496, were used along with its improved astrolabe, by Vasco da Gama and Pedro Álvares Cabral.

Sailing techniques

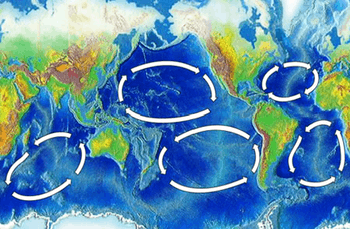

Besides coastal exploration, Portuguese also made trips off in the ocean to gather meteorological and oceanographic information (in these were discovered the archipelagos of Madeira and the Azores, and Sargasso Sea). The knowledge of wind patterns and currents – the trade winds and the oceanic gyres in the Atlantic, and the determination of latitude led to the discovery of the best ocean route back from Africa: crossing the Central Atlantic to the latitude of the Azores, using the permanent favorable winds and currents that spin clockwise in the Northern Hemisphere because of atmospheric circulation and the effect of Coriolis, facilitating the way to Lisbon and thus enabling the Portuguese venturing increasingly farther from shore, the maneuver that became known as "Volta do mar". In 1565, the application of this principle in the Pacific Ocean led the Spanish discovering the Manila Galleon trade route.

Cartography

It is thought that Jehuda Cresques, son of the Catalan cartographer Abraham Cresques have been one of the notable cartographers at the service of Prince Henry. However the oldest signed Portuguese sea chart is a Portolan made by Pedro Reinel in 1485 representing the Western Europe and parts of Africa, reflecting the explorations made by Diogo Cão. Reinel was also author of the first nautical chart known with an indication of latitudes in 1504 and the first representation of an Wind rose.

With his son, cartographer Jorge Reinel and Lopo Homem, they participated in the making of the atlas known as "Lopo Homem-Reinés Atlas" or "Miller Atlas", in 1519. They were considered the best cartographers of their time, with Emperor Charles V wanting them to work for him. In 1517 King Manuel I of Portugal handed Lopo Homem a charter gaving him the privilege to certify and amend all compass needles in vessels.

In the third phase of the former Portuguese nautical cartography, characterized by the abandonment of the influence of Ptolemy's representation of the East and more accuracy in the representation of lands and continents, stands out Fernão Vaz Dourado (Goa ~ 1520 – ~ 1580), giving him a reputation as one of the best cartographers of the time. Many of his charts are large scale.

Chronology

- 1147—Voyage of the Adventurers. Soon before the siege of Lisbon by Afonso I of Portugal, a Muslim expedition left in search of legendary Islands offshore. They were not heard of again.

- 1336—Possible first expedition to the Canary Islands with additional expeditions in 1340 and 1341, though this is disputed.[42]

- 1412—Prince Henry, the Navigator, orders the first expeditions to the African Coast and Canary Islands.

- 1415- Conquest of Ceuta (North Africa)

- 1419—João Gonçalves Zarco and Tristão Vaz Teixeira discovered Porto Santo island, in the Madeira group.

- 1420—The same sailors and Bartolomeu Perestrelo discovered the island of Madeira, which at once began to be colonized.

- 1422—Cape Nao, the limit of Moorish navigation is passed as the African Coast is mapped.

- 1427—Diogo de Silves discovered the Azores, which was colonized in 1431 by Gonçalo Velho Cabral.

- 1434—Gil Eanes sailed round Cape Bojador, thus destroying the legends of the ‘Dark Sea’.

- 1434—the 32 point compass-card replaces the 12 points used until then.

- 1435—Gil Eanes and Afonso Gonçalves Baldaia discovered Garnet Bay (Angra dos Ruivos) and the latter reached the Gold River (Rio de Ouro).

- 1441—Nuno Tristão reached Cape White.

- 1443—Nuno Tristão penetrated the Arguim Gulf. Prince Pedro granted Henry the Navigator the monopoly of navigation, war and trade in the lands south of Cape Bojador.

- 1444—Dinis Dias reached Cape Green (Cabo Verde).

- 1445—Álvaro Fernandes sailed beyond Cabo Verde and reached Cabo dos Mastros (Cape Red)

- 1446—Álvaro Fernandes reached the northern Part of Portuguese Guinea

- 1452—Diogo de Teive discovers the Islands of Flores and Corvo.

- 1455—Papal bull Romanus Pontifex confirmed the Portuguese explorations and declares that all lands and waters south of Bojador and cape Non (Cape Chaunar) belong to the kings of Portugal.

- 1458—Luis Cadamosto discovers the first Cape Verde Islands.

- 1458—Three capes discovered and named along the Grain Coast:(Grand Cape Mount, Cape Mesurado and Cape Palmas).

- 1460—Death of Prince Henry, the Navigator. His systematic mapping of the Atlantic, reached 8° N on the African Coast and 40° W in the Atlantic ( Sargasso Sea ) in his lifetime.

- 1461—Diogo Gomes and António de Noli discovered more of the Cape Verde Islands.

- 1461—Diogo Afonso discovered the western islands of the Cabo Verde group.

- 1471—João de Santarém and Pedro Escobar crossed the Equator. The southern hemisphere was discovered and the sailors began to be guided by a new constellation, the Southern Cross. The discovery of the islands of São Tome and Principe is also attributed to these same sailors.

- 1472—João Vaz Corte-Real and Álvaro Martins Homem reached the Land of Cod, now called Newfoundland.

- 1479—Treaty of Alcáçovas establishes Portuguese control of the Azores, Guinea, ElMina, Madeira and Cape Verde Islands and Castilian control of the Canary Islands.

- 1482—Diogo Cão reached the estuary of the Zaire (Congo) and placed a landmark there. Explored 150 km upriver to the Yellala Falls.

- 1484—Diogo Cão reached Walvis Bay, south of Namibia.

- 1487—Afonso de Paiva and Pero da Covilhã traveled overland from Lisbon in search of the Kingdom of Prester John. (Ethiopia)

- 1488—Bartolomeu Dias, crowning 50 years of effort and methodical expeditions, rounded the Cape of Good Hope and entered the Indian Ocean. They had found the "Flat Mountain" of Ptolemy's Geography.

- 1489/92—South Atlantic Voyages to map the winds

- 1490—Columbus leaves for Spain after his father-in-law's death.

- 1492—First exploration of the Indian Ocean.

- 1494—The Treaty of Tordesillas between Portugal and Spain divided the world into two parts, Spain claiming all non-Christian lands west of a north-south line 370 leagues west of the Azores, Portugal claiming all non-Christian lands east of that line.

- 1495—Voyage of João Fernandes, the Farmer, and Pedro Barcelos to Greenland. During their voyage they discovered the land to which they gave the name of Labrador (lavrador, farmer)

- 1494—First boats fitted with cannon doors and topsails.

- 1498—Vasco da Gama led the first fleet around Africa to India, arriving in Calicut.

- 1498—Duarte Pacheco Pereira explores the South Atlantic and the South American Coast North of the Amazon River.

- 1500—Pedro Álvares Cabral discovered Brazil on his way to India.

- 1500—Gaspar Corte-Real made his first voyage to Newfoundland, formerly known as Terras Corte-Real.

- 1500—Diogo Dias discovered an island they named after St Lawrence after the saint on whose feast day they had first sighted the island later known as Madagascar

- 1502— Returning from India, Vasco da Gama discovers the Amirante Islands (Seychelles).

- 1502—Miguel Corte-Real set out for New England in search of his brother, Gaspar. João da Nova discovered Ascension Island. Fernão de Noronha discovered the island which still bears his name.

- 1503—On his return from the East, Estêvão da Gama discovered Saint Helena Island.

- 1505—Gonçalo Álvares in the fleet of the first viceroy sailed south in the Atlantic to were "water and even wine froze" discovering an island named after him, modern Gough Island

- 1505—Lourenço de Almeida made the first Portuguese voyage to Ceylon (Sri Lanka) and established a settlement there.[43]

- 1506—Tristão da Cunha discovered the island that bears his name. Portuguese sailors landed on Madagascar.

- 1509—The Bay of Bengal crossed by Diogo Lopes de Sequeira. On the crossing he also reached Malacca.

- 1511— Duarte Fernandes is the first European to visit the Kingdom of Siam (Thailand), sent by Afonso de Albuquerque after the conquest of Malaca.[37]

- 1511-12 - João de Lisboa and Estevão de Fróis discovered the "Cape of Santa Maria" (Punta Del Este) in the River Plate, exploring its estuary (in present-day Uruguay and Argentina), and traveled as far south as the Gulf of San Matias at 42ºS (penetrating 300 km (186 mi) "around the Gulf"). Christopher de Haro, the financier of the expedition along with D. Nuno Manuel, bears witness of the news of the "White King" and "people of the mountains", the Inca empire - and the "axe of silver" (rio do "machado de prata") obtained from the Charrúa Indians and offered to king Manuel I.[44][45]

- 1512— António de Abreu discovered Timor island and reached Banda Islands, Ambon Island and Seram. Francisco Serrão reached the Moluccas.

- 1512—Pedro Mascarenhas discover the island of Diego Garcia, he also encountered the Mauritius, although he may not have been the first to do so; expeditions by Diogo Dias and Afonso de Albuquerque in 1507 may have encountered the islands. In 1528 Diogo Rodrigues named the islands of Réunion, Mauritius, and Rodrigues the Mascarene Islands, after Mascarenhas.

- 1513—The first European trading ship to touch the coasts of China, under Jorge Álvares and Rafael Perestrello later in the same year.

- 1514-1531— António Fernandes`s voyage and discoveries in 1514-1515,[46] Sancho de Tovar from 1515 onwards, and Vicente Pegado (1531), among others, in several expeditions and contacts, are the first Europeans ever to contemplate and to describe the ruins of Great Zimbabwe and those regions (then referred to by the Portuguese as Monomotapa).

- 1517—Fernão Pires de Andrade and Tomé Pires were chosen by Manuel I of Portugal to sail to China to formally open relations between the Portuguese Empire and the Ming Dynasty during the reign of the Zhengde Emperor.

- 1519-1521—Fernão de Magalhães's expedition at the service of the King Charles I of Spain and German "Holy Roman" Emperor, in search of a westward route to the "Spice Islands" (Maluku Islands) became the first known expedition to sail from the Atlantic Ocean into the Pacific Ocean (then named "peaceful sea" by Magellan; the passage being made via the Strait of Magellan), and the first to cross the Pacific. Besides Magellan, also participated in the trip Diogo and Duarte Barbosa, João Serrão, Álvaro de Mesquita (Magellan`s nephew), the pilots João Rodrigues de Carvalho and Estêvão Gomes, Henrique of Malacca, among others. Many of them cross almost all longitudes or all longitudes reaching the Philippines, Borneo and the Moluccas, because they had previously visited India, Mallacca, the Indonesian Archipelago or the Moluccas (1511-1512), like Ferdinand Magellan in the 7th Portuguese India Armada under the command of Francisco de Almeida and on the expeditions of Diogo Lopes de Sequeira, Afonso de Albuquerque and his other voyages, sailing eastward from Lisbon (as Magellan in 1505), and then later, in 1521, sailing westward from Seville, reaching that longitude and region once again and then proceeding still further west.

- 1525—Aleixo Garcia explored the Rio de la Plata in service to Spain as a member of the expedition of Juan Díaz de Solís in 1516. Solís had left Portugal towards Castile (Spain) in 1506 and would be financed by Christopher de Haro, who had served Manuel I of Portugal until 1516. Serving Charles I of Spain after 1516, Haro believed that Lisboa and Frois had discovered a major route in the Southern New World to west or a strait to Asia two years earlier. Later (when returning and after a shipwreck on the coast of Brazil), from Santa Catarina, Brazil, and leading an expedition of some European and 2,000 Guaraní Indians, Aleixo Garcia explored Paraguay and Bolivia using the trail network Peabiru. Aleixo Garcia was the first European to cross the Chaco and even managed to penetrate the outer defenses of the Inca Empire on the hills of the Andes (near Sucre), in present-day Bolivia. He was the first European to do so, accomplishing this eight years before Francisco Pizarro.

- 1525—Diogo da Rocha and his pilot Gomes de Sequeira reached Celebes and were blown off course and driven three hundred leagues in a direction constantly towards the east and to Ilhas de Gomes de Sequeira - most probably the Palau Island or Yap, (Caroline Islands) according to the geographical notes, distance traveled and physical description of the natives in Décadas da Ásia of João de Barros, or, according to the alleged existence of gold mentioned by the natives, other descriptions of the people and if they were to south and east in one or two voyages made by Gomes de Sequeira (According to the different interpretations of the Chronicles of Barros, Castanheda and Galvão), raises also the hypothesis of Cape York Peninsula in Australia, maybe one of the Prince of Wales Islands. In Gastald`s map a group of islands named Insul de gomes des queria lie in about 8 degrees of south latitude and in the longitude of the Northern Territory of Australia. In the same map the Apem insul seems to correspond with either Adi Island or the Aru Islands. The Ins des hobres blancos (Islands of the White Men) correspond, as far as locality is concerned, to the Arru (Aru) Islands. It would appear then that Gomes de Sequeira's Islands, which are the south-easternmost of those represented, must correspond with the Timor Laut group. In the same year, according to the voyages to the Banda Islands mencioned on Decadas and according to contemporaneous cartographers, Martim Afonso de Melo (Jusarte) and Garcia Henriques explored the Tanimbar Islands (the archipelago labelled "aqui invernou Martim Afonso de Melo" and "Aqui in bernon Martin Afonso de melo" [Here wintered Martin Afonso de Melo]) and probably the Aru Islands (the two archipelagos and the navigator mentioned in the maps of Lázaro Luís, 1563, Bartolomeu Velho, c. 1560, Sebastião Lopes, c. 1565 and also in the 1594 map of the East Indies entitled Insulce Molucoe by the Dutch cartographer Petrus Plancius and in the map of Nova Guinea of 1600).

- 1526—Discovery of New Guinea by Jorge de Meneses

- 1528—Diogo Rodrigues explores the Mascarene islands, that he names after his countryman Pedro Mascarenhas, he explored and named the islands of Réunion, Mauritius, and Rodrigues[47]

- 1529—Treaty of Saragossa divides the eastern hemisphere between Spain and Portugal, stipulating that the dividing line should lie 297.5 leagues or 17° east of the Moluccas.

- 1542—Fernão Mendes Pinto, Diogo Zeimoto and Cristovão Borralho reached Japan.

- 1542—The coast of California explored by João Rodrigues Cabrilho on behalf of Spain.

- 1557—Macau given to Portugal by the Emperor of China as a reward for services rendered against the pirates who infested the South China Sea.

- 1559— The Nau São Paulo commanded by Rui Melo da Câmara (was part of the Portuguese India Armada commanded by Jorge de Sousa) discovered Île Saint-Paul in the South Indian Ocean. The island was mapped, described and painted by members of the crew, among them the Father Manuel Álvares and the chemist Henrique Dias (Álvares and Dias calculated the correct latitude 38° South at the time of discovery). The Nau São Paulo, who also carried women and had sailed from Europe and had scale in Brazil, would be the protagonist of a dramatic and moving story of survival after sinking south of Sumatra.

- 1560—Gonçalo da Silveira, Jesuit missionary, travalled up the Zambezi River, on his expedition to the capital of the Monomotapa which appears to have been the N'Pande kraal, close by the M'Zingesi River, a southern tributary of the Zambezi. He arrived there on 26 December 1560.

- 1586—António da Madalena, a Capuchin friar, was one of the first Western visitors to Angkor (now Cambodja).

- 1602–1606—Bento de Góis, a Jesuit missionary, was the first known European to travel overland from India to China, via Afghanistan and the Pamirs.

- 1606—Pedro Fernandes de Queirós discovered Henderson Island, the Ducie Island and the islands later called the New Hebrides and now the nation of Vanuatu. Queirós landed on a large island which he took to be part of the southern continent, and named it La Austrialia del Espiritu Santo (The Austrian Land of the Holy Spirit), for King Philip III(II), or Australia of the Holy Spirit (Australia do Espírito Santo) of the southern continent.

- 1626—Estêvão Cacella, Jesuit missionary, traveled through the Himalayas and was the first European to enter Bhutan.[48]

- 1636-1638—Pedro Teixeira went from Belém do Pará up the Amazon River and reached Quito, Ecuador, in an expedition of over a thousand men. So Teixeira´s expedition became the first simultaneously to travel up and down the Amazon River.

- 1648-1651—António Raposo Tavares with 200 whites from São Paulo and over a thousand Indians travelled for over 10,000 kilometres (6,200 mi), in the biggest expedition ever made in the Americas, following the courses of the rivers, most notably the Paraguay River, to the Andes, the Grande River, the Mamoré River, the Madeira River and the Amazon River. Only Tavares, 59 whites and some Indians reached Belém at the mouth of the Amazon River.

References

Citations

- ↑ Patrick Karl O'Brien (2002). Atlas of World History. Oxford University Press. p. 118. ISBN 978-0-19-521921-0.

- ↑ Melvin Eugene Page; Penny M. Sonnenburg (2003). Colonialism: an International, Social, Cultural, and Political Encyclopedia. N-Z. Vol. 2. ABC-CLIO. p. 92. ISBN 978-1-57607-335-3.

- ↑ A. R. de Oliveira Marques, Vitor Andre, "Daily Life in Portugal in the Late Middle Ages", p.9, Univ of Wisconsin Press, 1971, ISBN 0-299-05584-1

- ↑ Diffie, Bailey (1977), Foundations of the Portuguese Empire, 1415–1580, p. 210, University of Minnesota Press. ISBN 0-8166-0782-6

- ↑ M. D. D. Newitt, "A history of Portuguese overseas expansion, 1400–1668", p.9, Routledge, 2005, ISBN 0-415-23979-6

- ↑ Butel, Paul, "The Atlantic", p. 36, Seas in history, Routledge, 1999 ISBN 0-415-10690-7

- ↑ Diffie, p. 56

- ↑ Rafiuddin Shirazi, Tazkiratul Mulk.

- ↑ Anderson, p. 50

- ↑ Diffie, p. 57–58

- ↑ Diffie, p. 60

- ↑ Diffie, p. 68

- ↑ Anderson, p. 44

- ↑ Daus, Ronald (1983). Die Erfindung des Kolonialismus. Wuppertal/Germany: Peter Hammer Verlag. p. 33. ISBN 3-87294-202-6.

- ↑ Boxer, p. 29

- ↑ Russell-Wood, p. 9

- ↑ Thorn, Rob. "Discoveries After Prince Henry". Retrieved 2006-12-24.

- ↑ Semedo, J. de Matos. "O Contrato de Fernão Gomes" (in Portuguese). Retrieved 2006-12-24.

- ↑ "Castelo de Elmina". Governo de Gana. Retrieved 2006-12-24.

- ↑ Anderson, p. 59

- ↑ Newitt, p. 47

- ↑ Anderson, p. 55

- ↑ Diffie, p. 174

- ↑ Diffie, p. 176

- ↑ Boxer, p. 36

- ↑ Scammell, p. 13

- ↑ McAlister, p. 75

- ↑ McAlister, p. 76

- ↑ Scammell, G.V. (1997). The First Imperial Age, European Overseas Expansion c. 1400–1715. Routledge. ISBN 0-415-09085-7.

- ↑ Bethencourt, Francisco. Curto, Diogo Ramada. (2007). Portuguese Overseas Expansion, 1400-1800. Cambridge University Press. p.142.

- ↑ "St. Francis Church". Wonderful Kerala. Retrieved 2008-02-21.

- ↑ Ayub, Akber (ed), Kerala: Maps & More, Fort Kochi, 2006 edition 2007 reprint, pp. 20–24, Stark World Publishing, Bangalore, ISBN 81-902505-2-3

- ↑ "European Encroachment and Dominance:The Portuguese". Sri Lanka: A Country Study. Retrieved 2006-12-02.

- ↑ Teotonio R. De Souza, "Goa Through the Ages: An economic history" p.220, Issue 6 of Goa University publication series, ISBN 81-7022-226-5,

- ↑ Indo-Portuguese Issues Indo-Portuguese Issues

- ↑ Ricklefs, M.C. (1991). A History of Modern Indonesia Since c. 1300, 2nd Edition. London: MacMillan, p.23. ISBN 0-333-57689-6.

- 1 2 Donald Frederick Lach, Edwin J. Van Kley, "Asia in the making of Europe", p.520–521, University of Chicago Press, 1994, ISBN 978-0-226-46731-3

- ↑ Juan Cole, Sacred Space and Holy War, IB Tauris, 2007 p37

- ↑ Sarina Singh, India, Lonely Planet, 2003, 726 pp. ISBN 1-74059-421-5.

- ↑ Arnold Pacey, "Technology in world civilization: a thousand-year history", ISBN 0-262-66072-5

- ↑ Yosaburō Takekoshi, "The Economic Aspects of the History of the Civilization of Japan", ISBN 0-415-32379-7.

- ↑ B. W. Diffie, Foundations of the Portuguese Empire, 1415 -1580, Minneapolis, University of Minnesota Press, p. 28.

- ↑ This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Wood, James, ed. (1907). "article name needed". The Nuttall Encyclopædia. London and New York: Frederick Warne.

- ↑ Newen Zeytung auss Presillg Landt

- ↑ Bethell, Leslie (1984). The Cambridge History of Latin America, Volume 1, Colonial Latin America. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 257.

- ↑ Rhodesiana: The Pioneer Head

- ↑ José Nicolau da Fonseca, Historical and Archaeological Sketch of the City of Goa, Bombay : Thacker, 1878, pp. 47–48. Reprinted 1986, Asian Educational Services, ISBN 81-206-0207-2.

- ↑ FATHER ESTEVAO CACELLA'S REPORT ON BHUTAN IN 1627.

Bibliography

- Abernethy, David (2000). The Dynamics of Global Dominance, European Overseas Empires 1415–1980. Yale University Press. ISBN 0-300-09314-4.

- Anderson, James Maxwell (2000). The History of Portugal. Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN 0-313-31106-4.

- Boxer, Charles Ralph (1969). The Portuguese Seaborne Empire 1415–1825. Hutchinson. ISBN 0-09-131071-7.

- Boyajian, James (2008). Portuguese Trade in Asia Under the Habsburgs, 1580–1640. JHU Press. ISBN 0-8018-8754-2.

- Davies, Kenneth Gordon (1974). The North Atlantic World in the Seventeenth Century. University of Minnesota Press. ISBN 0-8166-0713-3.

- Diffie, Bailey (1977). Foundations of the Portuguese Empire, 1415–1580. University of Minnesota Press. ISBN 0-8166-0782-6.

- Diffie, Bailey (1960). Prelude to empire: Portugal overseas before Henry the Navigator. U of Nebraska Press. ISBN 0-8032-5049-5.

- Lockhart, James (1983). Early Latin America: A History of Colonial Spanish America and Brazil. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-29929-2.

- McAlister, Lyle (1984). Spain and Portugal in the New World, 1492–1700. University of Minnesota Press. ISBN 0-8166-1216-1.

- Newitt, Malyn D.D. (2005). A History of Portuguese Overseas Expansion, 1400–1668. Routledge. ISBN 0-415-23979-6.

- Russell-Wood, A.J.R. (1998). The Portuguese Empire 1415–1808. Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 0-8018-5955-7.

- Scammell, Geoffrey Vaughn (1997). The First Imperial Age, European Overseas Expansion c.1400–1715. Routledge. ISBN 0-415-09085-7.