John Leslie (physicist)

| John Leslie | |

|---|---|

|

John Leslie | |

| Born |

10 April 1766 Largo, Fife |

| Died | 3 November 1832 (aged 66) |

| Nationality | Scottish |

| Fields |

Mathematics Physics |

| Known for |

Studies of heat Leslie cube |

| Influences | David Hume[1] |

| Notable awards | Rumford Medal (1804) |

Sir John Leslie, KH (10 April 1766 – 3 November 1832) was a Scottish mathematician and physicist best remembered for his research into heat.

Leslie gave the first modern account of capillary action in 1802 and froze water using an air-pump in 1810, the first artificial production of ice.

In 1804, he experimented with radiant heat using a cubical vessel filled with boiling water. One side of the cube is composed of highly polished metal, two of dull metal (copper) and one side painted black. He showed that radiation was greatest from the black side and negligible from the polished side. The apparatus is known as a Leslie cube.

Early life

Leslie was born of humble parentage at Largo in Fife and received his early education there and at Leven. In his thirteenth year, encouraged by friends who had even then remarked his aptitude for mathematical and physical science, he entered the University of St Andrews. On the completion of his arts course, he nominally studied divinity at Edinburgh until 1787.

From 1788–1789 he spent rather more than a year as private tutor in a Virginian family, and from 1791 till the close of 1792 he held a similar appointment at Etruria, Staffordshire, with the family of Josiah Wedgwood, employing his spare time in experimental research and in preparing a translation of Buffon's Natural History of Birds, which was published in nine volumes in 1793, which brought him money.

Middle years

For the next twelve years (passed chiefly in London or at Largo, with an occasional visit to the continent of Europe) he continued his physical studies, which resulted in numerous papers contributed by him to Nicholson's Philosophical Journal, and in the publication (1804) of the Experimental Inquiry into the Nature and Properties of Heat, a work which gained him the Rumford Medal of the Royal Society of London.

In 1805 he was elected to succeed John Playfair in the chair of mathematics at Edinburgh. This despite violent opposition on the part of a party who accused him of heresy.

During his tenure of this chair he published two volumes of A Course of Mathematics-the first, entitled Elements of Geometry, Geometrical Analysis and Plane Trigonometry, in 1809, and the second, Geometry of Curve Lines, in 1813; the third volume, on Descriptive Geometry and the Theory of Solids was never completed. With reference to his invention (in 1810) of a process of artificial ice-making, he published in 1813 A Short Account of Experiments and Instruments depending on the relations of Air to Heat and Moisture; and in 1818 a paper by him, On certain impressions of cold transmitted from the higher atmosphere, with an instrument (the aethrioscope) adapted to measure them, appeared in the Transactions of the Royal Society of Edinburgh.

In 1807 he became a member of the Royal Society of Edinburgh.[2]

Later years

When Playfair died in 1819, Leslie was promoted to the more congenial chair of natural philosophy, which he held until his death. He published a famous book about multiplication table The Philosophy of Arithmetic in 1820.[3] In 1823 he published, chiefly for the use of his class, the first volume of his never-completed Elements of Natural Philosophy.

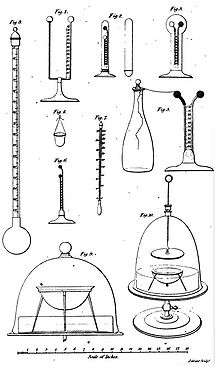

Leslie's main contributions to physics were made by the help of the differential thermometer,[4] an instrument whose invention was contested with him by Count Rumford. By adapting to this instrument various ingenious devices, Leslie was able to employ it in a great variety of investigations, connected especially with photometry, hygroscopy and the temperature of space. In 1820 he was elected a corresponding member of the Institute of France, the only distinction of the kind which he valued, and early in 1832 he was knighted.

In his final years he is listed as living at 62 Queen Street, a large Georgian flat in Edinburgh's New Town.[5]

Leslie died of typhus[6] in November 1832 (during the epidemic of that year) at Coates, a small property he had acquired near Largo in Fife, at the age of 66.

Family

His nephew was the civil engineer, James Leslie, son of his brother, Alexander Leslie, an architect-builder in Largo.

Selected works

- An Experimental Inquiry into the Nature and Propagation of Heat (1804)

- Elements of Geometry, Geometrical Analysis, and Plane Trigonometry (ca. 1811)

- Second edition (1811)

- Geometrische Analysis (1822) "Greatly" enlarged by Johann Philipp Grüson (German)

- A Short Account of Experiments and Instruments, Depending on the Relations of Air to Heat and Moisture (1813)

- Second supplément de la géométrie descriptive[7] (with Gaspard Monge and Jean Nicolas Pierre Hachette) (1818) (French)

- Philosophy of Arithmetic; Exhibiting a Progressive View of the Theory and Practice of Calculation, with an Enlarged Table of the Products of Numbers under One Hundred (1817).

- Geometrical Analysis and Geometry of Curve Lines being Volume the Second of A Course of Mathematics and designed as an Introduction to the Study of Natural Philosophy [Edinburgh Printed for W and C Tait, Prince's Street and Longman Hurst Rees Orme and Brown, London 1821]

Literature

- E. M. Horsburgh (1933). "The Works of Sir John Leslie (1766–1832)". Mathematical Notes, 28, pp i-v. doi:10.1017/S1757748900002279.

See also

- Atmometer (evaporimeter)

- Timeline of low-temperature technology

References

- ↑ The Reception of David Hume In Europe, edited by Peter Jones, Continuum International Publishing Group, 2005, p. 333.

- ↑ Transactions of the Royal Society of Edinburgh, vol. 9, p. 518.

- ↑ Leslie, John (1820). The Philosophy of Arithmetic; Exhibiting a Progressive View of the Theory and Practice of Calculation, with Tables for the Multiplication of Numbers as Far as One Thousand. Edinburgh: Abernethy & Walker.

- ↑ Photographs of differential thermometers.

- ↑ http://digital.nls.uk/directories/browse/pageturner.cfm?id=83400891&mode=transcription

- ↑ London Medical and Surgical Journal, January 1833

- ↑ Géométrie descriptive is a book by Monge (1799).

Further reading

- Olson, Richard G. (1969). "Sir John Leslie and the Laws of Electrical Conduction in Solids". American Journal of Physics. 37 (2): 190–194. Bibcode:1969AmJPh..37..190O. doi:10.1119/1.1975442.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to John Leslie (physicist). |

![]() This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Leslie, Sir John". Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Leslie, Sir John". Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

_by_Ambroise_Tardieu.jpg)