Nematology

Nematology is the scientific discipline concerned with the study of nematodes, or roundworms. Although nematological investigation dates back to the days of Aristotle or even earlier, nematology as an independent discipline has its recognizable beginnings in the mid to late 19th century.[1][2]

History: pre-1850

Nematology research, like most fields of science, has its foundations in observations and the recording of these observations. The earliest written account of a nematode "sighting," as it were, may be found in the Pentateuch of the Old Testament in the Bible, in the Fourth Book of Moses called Numbers: "And the Lord sent fiery serpents among the people, and they bit the people; and much people of Israel died".[3] Although no empirical data exists to test the hypothesis, many nematologists assume and circumstantial evidence suggests the "fiery serpents" to be the Guinea worm, Dracunculus medinensis, as this nematode is known to inhabit the region near the Red Sea.[2]

Before 1750, a large number of nematode observations were recorded, many by the notable great minds of ancient civilization. Hippocrates[4] (ca. 420 B.C.), Aristotle[5] (ca. 350 B.C.), Celsus[6] (ca 10 B.C.), Galen[7] (ca. 180 A.D.) and Redi[8] (1684) all described nematodes parasitizing humans or other large animals and birds. Borellus[9] (1653) was the first to observe and describe a free-living nematode, which he dubbed the "vinegar eel;" and Tyson[10] (1683) used a crude microscope to describe the rough anatomy of the human intestinal roundworm, Ascaris lumbricoides.

Other well-known microscopists spent time observing and describing free-living and animal-parasitic nematodes: Hooke[11] (1683), Leeuwenhoek [12] (1722), Needham[13] (1743), and Spallanzani[14] (1769) are among these.[2] Observations and descriptions of plant parasitic nematodes, which were less conspicuous to ancient scientists, didn't receive as much or as early attention as did animal parasites. The earliest allusion to a plant parasitic nematode is, however, preserved in famous writ. "Sowed cockle, reap'd no corn," a line by William Shakespeare penned in 1594 in Love's Labour's Lost, Act IV, Scene 3, most certainly has reference to blighted wheat caused by the plant parasite, Anguina tritici.[15]

Needham[13] (1743) solved the "riddle of cockle" when he crushed one of the diseased wheat grains and observed "Aquatic Animals...denominated Worms, Eels, or Serpents, which they very much resemble." It is likely that few or no other recorded observations of plant parasitic nematodes or their effects are to be found in ancient literature.[16]

From 1750 to the early 1900s, nematology research continued to be descriptive and taxonomic, focusing primarily on free-living nematodes and plant and animal parasites.[17] During this period a number of productive researchers contributed to the field of nematology in the United States and abroad. Beginning with Needham and continuing to Cobb, nematologists compiled and continuously revised a broad descriptive morphological taxonomy of nematodes.

History: 1850 to the present

Kuhn[18] (1874) is thought to be the first to use soil fumigation to control nematodes, applying carbon disulfide treatments in sugar beet fields in Germany. In Europe from 1870 to 1910, nematological research focused heavily on controlling the sugar beet nematode as sugar beet production became an important economy during this time in the Old World.[15]

Although 18th and 19th century scientists yielded a considerable amount of important fundamental and applied knowledge about nematode biology, nematology research really began to advance in quality and quantity near the turn of the 20th century. In 1918, the first permanent nematology field station was constructed in the U.S. Post Office in Salt Lake City, Utah under the direction of Harry B. Shaw, after scientists observed the sugar beet nematode in a field south of the city.[15] In this same year, Nathan Cobb (1918) published his Contributions to a Science of Nematology and his lab manual "Estimating the Nema Population of Soil."[19] These two publications provide definitive resources for many methods and apparatus used in nematology even to this day.[15]

Of Cobb's far-reaching influence on nematology research, Jenkins and Taylor[20] write:

- Although many workers have played important roles in development of plant nematology, none have had a greater impact, particularly in the United States, than N.A. Cobb. In 1913 Cobb published his first paper on nematology in the United States. From [1913] to 1932 he was the undisputed leader in [nematology] in this country. Through his efforts the widely renowned [USDA] nematology research program was initiated and developed. Many of his students and colleagues developed into the leaders in plant nematology in the 1930s, 1940's, and 1950's. In addition, during his productive career he contributed major discoveries in the areas of nematode taxonomy, morphology, and in methodology. Many of his techniques are still unsurpassed!

Perhaps no one person has had as favorable an impact on the field of nematology as has Nathan Augustus Cobb.

From 1900–1925 various state-run agricultural experimental stations investigated important problems relating to agro-economy, though few stations devoted much attention to plant-parasitic nematodes. Accounts of the history of nematology (the few that exist) mention three major events occurring between 1926 and 1950 that affected the relative importance of nematodes in the eyes of farmers, legislators and the U.S. public in general. These same events had profound worldwide effects on the course of nematology research over the next fifty to seventy-five years

First, the discovery of the golden nematode in the potato fields of Long Island led to a trip by U.S. quarantine officials to the potato fields of Europe, where the devastating effects of this parasite had been known for many years. This excursion allayed all skepticism about the seriousness of this agricultural pest. Second, the introduction of the soil fumigants, D-D and EDB made available for the first time nematicides that could be used effectively and practically on a field scale. Third, the development of nematode-resistant crop cultivars brought substantial government funding to applied nematology research.[15][17][21]

These events contributed to a shift from broad taxonomy-based nematology research to deep, yet focused investigations of plant parasitic nematodes, especially the control of agricultural pests. From the early 1930s until recently, the bulk of researchers studying nematodes have been plant pathologists by training.[17] Consequently, nematological research leaned heavily toward answering plant pathological and agro-economical questions for the last three-quarters of the 20th century.

Notable nematologists

Contributions to other sciences

Nematologists in the 1800s also contributed to other scientific fields in important ways. Butschli[22] (1875) first observed the formation of polar bodies by nuclear subdivision in a nematode, Beneden[23] (1883) was studying Ascaris megalocephala when he discovered the separation of halves of each of the chromosomes from the two parents and the mechanism of Mendelian heredity, and Boveri[24] (1893) showed evidence for continuity of the germ plasm and that the soma may be regarded as a by-product without influence upon heredity.[2]

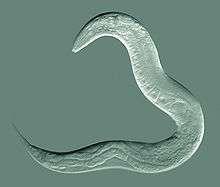

Caenorhabditis elegans is a widely used model species, initially for neural development, and then for genetics. WormBase collates research on the species.

References

- ↑ Chen, Z. X., Chen, S. Y., and Dickson, D. W. (2004). "A Century of Plant Nematology", pp. 1–42 in Nematology Advances and Perspectives, Vol 1. Tsinghua University Press, Beijing, China.

- 1 2 3 4 Chitwood, B. G., and Chitwood, M. B. (1950). "An Introduction to Nematology", pp. 1–5 in Introduction to Nematology. University Park Press, Baltimore.

- ↑ Holy Bible, King James Version. (1979) p. 227. The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. Salt Lake City, Utah.

- ↑ Hippocrates (460-375 B.C.) 1849. Works of Hippocrates, translated by F. Adams. London, "Aphorisms."

- ↑ Aristotle (384-322 B.C.) 1910. Historia animalium. Translated by D'Arcy Wentworth Thompson. In: Works. J. A. Smith and W. D. Ross, eds. Vol. IV. Garrison Morton.

- ↑ Celsus, A. C. (53 B.C.-7 A.D.) 1657. De medicina libri octo, ex recognitione Joh. Antonidae von Linden D. & Prof. Med. Pract. Ord.

- ↑ Galen, C. (130–200) 1552. De simplicum medicamentorum faculatibus libre xi. Lugdoni.

- ↑ Redi, F. (1684) p. 253 in Osservazioni...intorno agli animali viventi che si trovano negli animali viventi. 26 pls. Firenze.

- ↑ Borellus, P. (1653) p. 240 in Historiarum, et observationum medicophysicarum, centuria prima, etc. Castris.

- ↑ Tyson, E. (1683). "Lumbricus Teres, or Some Anatomical Observations on the Round Worm Bred in Human Bodies. By Edward Tyson M. D. Col. Med. Lond. Nec Non. Reg. Societ. Soc". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. 13 (143–154): 154. doi:10.1098/rstl.1683.0023.

- ↑ Hooke, R. (1667). Micrographia: etc. London.

- ↑ Leeuwenhoek, O. (1722). Opera omnia seu arcana naturae (etc.). Lugduni Batavorum.

- 1 2 Needham, T. (1742). "A Letter from Mr. Turbevil Needham, to the President; Concerning Certain Chalky Tubulous Concretions, Called Malm: With Some Microscopical Observations on the Farina of the Red Lily, and of Worms Discovered in Smutty Corn". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. 42 (462–471): 634. doi:10.1098/rstl.1742.0101.

- ↑ Spallanzani, L. (1769). Nouvelles recherches sur les decouvertes microscopiques, etc. Londres & Paris.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Thorne, G. (1961). "Introduction", pp. 1–21 in Principles of Nematology. McGraw-Hill Book Company, Inc., New York.

- ↑ Steiner, G. (1960). "Nematology-An Outlook", pp. 3–7 in Nematology: Fundamentals and Recent Advances. J. N. Sasser and W. R. Jenkins, eds. The University of North Carolina Press, Chapel Hill.

- 1 2 3 Van Gundy, S. D. (1987). "Perspectives on Nematology Research", pp. 28–31 in Vistas on Nematology. J. A. Veech and D. W. Dickson, eds. Society of Nematologists, Inc. Hyattsville, Maryland.

- ↑ Kuhn, J. (1874). "Ubers das Vorkommen von Ruben-Nematoden an den Wurzeln der Halmfruchte". Landwirts. Jahrb. 3:47–50.

- ↑ Cobb, N. A. (1918). "Estimating the nema population of soil". U.S. Department of Agriculture, Bur. Plant. Indrusty, Agr. Tech. Cir. 1:1–48.

- ↑ Jenkins, W. R., and Taylor, D. P. (1967). "Introduction", p. 7 in Plant Nematology. Reinhold Publishing Corporation, New York.

- ↑ Christie, J. R. (1960). "The Role of the Nematologist", pp. 8–11 in Nematology: Fundamentals and Recent Advances. J. N. Sasser and W. R. Jenkins, eds. The University of North Carolina Press, Chapel Hill.

- ↑ Butschli, O. (1875). "Vorlaufige Mittheilung uber Untersuchungen betreffend die ersten Entwickelungsvorgange im befruchehen Ei von Nematoden und Schnecken". Ztschr. Wiss. Zool. v. 25:201–213.

- ↑ Beneden, E. van. (1883). Recherches sur la maturation de l'oeuf, la fecondation et la division cellulaire. Gand & Leipzig.

- ↑ Boveri, T. (1893). "Ueber die Entstehung des Gegensatzes zwischen den Geschlectszellen und den somatischen Zellen bei Ascaris megalocephala, nebst Bemerkungen zur Entwicklungsgeschichte der Nematoden". Sitzungsb. Gesellsch. Morph. u. Physiol. in Munchen.

Further reading

- Mai, W. F., and Motsinger, R. E. 1987. History of the Society of Nematologists. Pages 1–6 in: Vistas on Nematology. J. A. Veech and D. W. Dickson, eds. Society of Nematologists, Inc. Hyattsville, Maryland.

- Van Gundy, S.D. 1980. Nematology – status and prospects: Let's take off our blinders and broaden our horizons. Journal of Nematology 18:129–135.