Juke joint

Juke joint (or jook joint) is the vernacular term for an informal establishment featuring music, dancing, gambling, and drinking, primarily operated by African American people in the southeastern United States. The term "juke" is believed to derive from the Gullah word joog, meaning rowdy or disorderly. A juke joint may also be called a "barrelhouse".

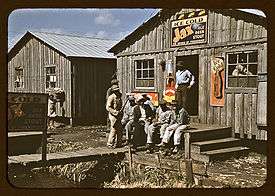

Classic juke joints found, for example, at rural crossroads, catered to the rural work force that began to emerge after the emancipation.[1] Plantation workers and sharecroppers needed a place to relax and socialize following a hard week, particularly since they were barred from most white establishments by Jim Crow laws. Set up on the outskirts of town, often in ramshackle buildings or private houses, juke joints offered food, drink, dancing and gambling for weary workers.[2] Owners made extra money selling groceries or moonshine to patrons, or providing cheap room and board.

History

The origins of juke joints may be the community rooms that were occasionally built on plantations to provide a place for blacks to socialize during slavery. This practice spread to the work camps such as sawmills, turpentine camps and lumber companies in the early twentieth century, which built barrel-houses and chock-houses to be used for drinking and gambling. Although uncommon in populated areas, such places were often seen as necessary to attract workers to sparsely populated areas lacking bars and other social outlets. As well, much like "on-base" Officer's Clubs, such "Company"-owned joints allowed managers to keep an eye on their underlings; it also ensured that the employees' pay was coming back to the Company. Constructed simply like a field hand's "shotgun"-style dwelling, these may have been the first juke joints. During the prohibition in the United States it became common to see squalid independent juke joints at highway crossings and railroad stops. These were almost never called "juke joint"; but rather were named such as "Lone Star" or "Colored Cafe". They were often open only on weekends.[3] Juke joints may represent the first "private space" for blacks.[4] Paul Oliver writes that juke joints were "the last retreat, the final bastion for black people who want to get away from whites, and the pressures of the day."[3]

Jooks occurred on plantations, and classic juke joints found, for example, at rural crossroads began to emerge after the Emancipation Proclamation.[5] Dancing was done to so-called jigs and reels (terms routinely used for any dance that struck respectable people as wild or unrestrained, whether Irish or African), to music now thought of as "old-timey" or "hillbilly". Through the first years of the twentieth century, the fiddle was by far the most popular instrument among both white and black Southern musicians. The banjo was popular before guitars became widely available in the 1890s.[6]

Juke joint music began with the black folk rags ("ragtime stuff" and "folk rags" are a catch-all term for older African American music[7]) and then the boogie woogie dance music of the late 1880s or 1890s and became the blues, barrel house, and the slow drag dance music of the rural south (moving to Chicago's black rent-party circuit in the Great Migration) often "raucous and raunchy"[8] good time secular music. Dance forms evolved from ring dances to solo and couples dancing. Some blacks opposed the amorality of the raucous "jook crowd".[8]

Until the advent of the Victrola, and juke boxes, at least one musician was required to provide music for dancing, but as many as three musicians would play in jooks.[9] In larger cities like New Orleans, string trios or quartets were hired.[10]

Mance Lipscomb, Texas guitarist and singer: "So far as what was called blues, that didn't come till 'round 1917...What we had in my coming up days was music for dancing, and it was of all different sorts." Musicians of that time had a degree of versatility that is now extremely rare, and styles were not yet codified and there was a good deal of shading and overlap.[6]

Paul Oliver, who tells of a visit to a juke joint outside of Clarksdale some forty years ago and was the only white man there, describes juke joints of the time as, "unappealing, decrepit, crumbling shacks" that were often so small that only a few couples could Hully Gully. The outside yard was filled with trash. Inside they are "dusty" and "squalid" with the walls "stained to shoulder height".[3]

In 1934, anthropologist Zora Neale Hurston made the first formal attempt to describe the juke joint and its cultural role, writing that "the Negro jooks...are primitive rural counterparts of resort night clubs, where turpentine workers take their evening relaxation deep in the pine forests." Jukes figure prominently in her studies of African American folklore.[11]

Early figures of blues, including Robert Johnson, Son House, Charley Patton, and countless others, traveled the juke joint circuit, scraping out a living on tips and free meals. While musicians played, patrons enjoyed dances with long heritages in some parts of the African American community, such as the slow drag.

Many of the early and historic juke joints have closed over the past decades for a number of socio-economic reasons. Po' Monkey's is one of the last remaining rural jukes in the Mississippi Delta. It began as a renovated sharecropper's shack which was probably originally built in the 1920s or so.[12] Po' Monkey's features live blues music and "Family Night" on Thursday nights.[12] Run by Po' Monkey until his death in 2016,[13] the popular juke joint has been featured in national and international articles about the Delta. The Blue Front Cafe is a historic old juke joint made of cinder blocks in Bentonia, Mississippi which played an important role in the development of the blues in Mississippi. It was still in operation as of 2006.[14] Smitty's Red Top Lounge in Clarksdale, Mississippi, is also still operating as of last notice.[15]

Juke joints are still a strong part of African American culture in Deep South locations such as the Mississippi Delta where blues is still the mainstay, although it is now more often featured by disc jockeys and on jukeboxes than by live bands.

Urban juke joint

Peter Guralnick describes many Chicago juke joints as corner bars that go by an address and have no name. The musicians and singers perform unannounced and without microphones, ending with little if any applause. Guralnick tells of a visit to a specific juke joint, Florence's, in 1977. In stark contrast to the streets outside, Florence's is dim, and smoke-filled with the music more of an accompaniment to the "various business" being conducted than the focus of the patrons' attention. The "sheer funk of all those closely-packed-together bodies, the shouts and laughter" draws his attention. He describes the security measures and buzzer at the door, there having been a shooting there a few years ago. On this particular day Magic Slim was performing with his band, the Teardrops, on a bandstand barely big enough to hold the band.[16]

Katrina Hazzard-Gordon writes that "[t]he honky-tonk was the first urban manifestation of the jook, and the name itself later became synonymous with a style of music. Related to the classic blues in tonal structure, honky-tonk has a tempo that is slightly stepped up. It is rhythmically suited for many African-American dances…", but cites no reference.[17]

Legacy

The low-down allure of juke joints has inspired many large-scale commercial establishments, including the House of Blues chain, the 308 Blues Club and Cafe in Indianola, Mississippi[18] and the Ground Zero in Clarksdale, Mississippi. Traditional juke joints, however, are under some pressure from other forms of entertainment, including casinos.

Jukes have been celebrated in photos and film. Marion Post Wolcott's images of the dilapidated buildings and the pulsing life they contained are among the most famous documentary images of the era.

See also

References

- ↑ Hazzard-Gordon, Katrina (1990). Jookin': The Rise of Social Dance Formations in African-American Culture. Philadelphia: Temple University Press. p. 80. ISBN 087722613X. OCLC 19515231.

- ↑ Gorman, Juliet. "Cultural Migrancy, Jooks, and Photographs". www.oberlin.edu. Retrieved 2008-06-08.

- 1 2 3 Oliver, Paul (1984). Blues Off the Record:Thirty Years of Blues Commentary. New York: Da Capo Press. pp. 45–47. ISBN 0-306-80321-6.

- ↑ Gorman, Juliet. "Backwoods Identities". www.oberlin.edu. Retrieved 2008-06-08.

- ↑ Hazzard-Gordon (1990). Jookin'. pp. 80, 105.

- 1 2 Wald, Elijah (2004). Escaping the Delta: Robert Johnson and the Invention of the Blues. HarperCollins. pp. 45–46. ISBN 0-06-052423-5.

- ↑ Wald (2004). Escaping the Delta. pp. 43–44.

- 1 2 Floyd, Jr., Samuel (1995). The Power of Black Music. New York: Oxford University Press. pp. 66–67, 122. ISBN 0-19-508235-4.

- ↑ Hazzard-Gordon (1990). Jookin'. pp. 82–83.

- ↑ Hazzard-Gordon (1990). Jookin'. p. 87.

- ↑ Gorman, Juliet. "What is a Jook Joint?". www.oberlin.edu. Retrieved 2008-06-08.

- 1 2 Brown, Luther (22 June 2006). "Inside Poor Monkey's". Southern Spaces. Retrieved 2008-06-07.

- ↑ "Willie Seaberry, Owner of Mississippi's Po' Monkey's Juke Joint, Dies at 75". Afro.com. Retrieved 2016-11-15.

- ↑ "Blue Front Cafe a sure stop along Mississippi Blues Trail". USA Today. 3 July 2006. Retrieved 2008-05-27.

- ↑ "Juke-joints". www.steberphoto.com. Retrieved 2008-06-07.

- ↑ Guralnick, Peter (1989). Lost Highway: Journeys and Arrivals of American Musicians. New York: Harper & Row. pp. 304–305. ISBN 0060971746.

- ↑ Hazzard-Gordon (1990). "Shoddy Confines: The Jook Continuum". Jookin'. p. 84.

- ↑ "308 Blues Club and Cafe". www.308bluesclubandcafe.com. Retrieved 2008-06-07.

Further reading

- Cobb, Charles E., Jr., "Traveling the Blues Highway", National Geographic Magazine, April 1999, v.195, n.4

- Hamilton, Marybeth: In Search of the Blues.

- William Ferris; - Give My Poor Heart Ease: Voices of the Mississippi Blues - The University of North Carolina Press; (2009) ISBN 0-8078-3325-8 ISBN 978-0807833254 (with CD and DVD)

- William Ferris; Glenn Hinson The New Encyclopedia of Southern Culture: Volume 14: Folklife The University of North Carolina Press (2009) ISBN 0-8078-3346-0 ISBN 978-0-8078-3346-9 (Cover :phfoto of James Son Thomas)

- William Ferris; Blues From The Delta Da Capo Press; Revised edition (1988) ISBN 0-306-80327-5 ISBN 978-0306803277

- Ted Gioia; Delta Blues: The Life and Times of the Mississippi Masters Who Revolutionized American Music - W. W. Norton & Company (2009) ISBN 0-393-33750-2 ISBN 978-0393337501

- Sheldon Harris; Blues Who's Who Da Capo Press 1979

- Robert Nicholson; Mississippi Blues Today ! Da Capo Press (1999) ISBN 0-306-80883-8 ISBN 978-0-306-80883-8

- Robert Palmer; Deep Blues: A Musical and Cultural History of the Mississippi Delta - Penguin Reprint edition (1982) ISBN 0-14-006223-8; ISBN 978-0-14-006223-6

- Frederic Ramsey Jr.; Been Here And Gone - 1st edition (1960) Rutgers University Press - London Cassell (UK) andNew Brunswick, NJ

- idem - 2nd printing (1969) Rutgers University Press New Brunswick, NJ

- idem - (2000) University Of Georgia Press

- Charles Reagan Wilson - William Ferris - Ann J. Adadie; Encyclopedia of Southern Culture (1656 pagine) The University of North Carolina Press; 2nd Edition (1989) - ISBN 0-8078-1823-2 - ISBN 978-0-8078-1823-7

External links

- A collection of Juke Joint Blues musicians and playlists

- Random House Word of the Day . Accessed 2006-02-02.

- Junior's Juke Joint. Accessed 2006-02-01.

- Juke Joint Festival. Accessed 2006-02-02.

- "Backroads of American Music". www.backroadsofamericanmusic.com. Retrieved 2008-06-08.

- Jukin' It Out: Contested Visions of Florida in New Deal Narratives

- Juke Joint video

- Juke Joint at Queens