Seven Bridges of Königsberg

The Seven Bridges of Königsberg is a historically notable problem in mathematics. Its negative resolution by Leonhard Euler in 1736 laid the foundations of graph theory and prefigured the idea of topology.[1]

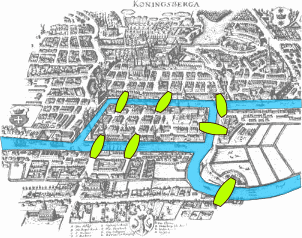

The city of Königsberg in Prussia (now Kaliningrad, Russia) was set on both sides of the Pregel River, and included two large islands which were connected to each other and the mainland by seven bridges. The problem was to devise a walk through the city that would cross each bridge once and only once, with the provisos that: the islands could only be reached by the bridges and every bridge once accessed must be crossed to its other end. The starting and ending points of the walk need not be the same.

Euler proved that the problem has no solution. The difficulty was the development of a technique of analysis and of subsequent tests that established this assertion with mathematical rigor.

Euler's analysis

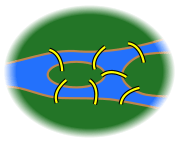

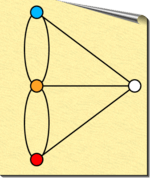

First, Euler pointed out that the choice of route inside each land mass is irrelevant. The only important feature of a route is the sequence of bridges crossed. This allowed him to reformulate the problem in abstract terms (laying the foundations of graph theory), eliminating all features except the list of land masses and the bridges connecting them. In modern terms, one replaces each land mass with an abstract "vertex" or node, and each bridge with an abstract connection, an "edge", which only serves to record which pair of vertices (land masses) is connected by that bridge. The resulting mathematical structure is called a graph.

→

→

→

→

Since only the connection information is relevant, the shape of pictorial representations of a graph may be distorted in any way, without changing the graph itself. Only the existence (or absence) of an edge between each pair of nodes is significant. For example, it does not matter whether the edges drawn are straight or curved, or whether one node is to the left or right of another.

Next, Euler observed that (except at the endpoints of the walk), whenever one enters a vertex by a bridge, one leaves the vertex by a bridge. In other words, during any walk in the graph, the number of times one enters a non-terminal vertex equals the number of times one leaves it. Now, if every bridge has been traversed exactly once, it follows that, for each land mass (except for the ones chosen for the start and finish), the number of bridges touching that land mass must be even (half of them, in the particular traversal, will be traversed "toward" the landmass; the other half, "away" from it). However, all four of the land masses in the original problem are touched by an odd number of bridges (one is touched by 5 bridges, and each of the other three is touched by 3). Since, at most, two land masses can serve as the endpoints of a walk, the proposition of a walk traversing each bridge once leads to a contradiction.

In modern language, Euler shows that the possibility of a walk through a graph, traversing each edge exactly once, depends on the degrees of the nodes. The degree of a node is the number of edges touching it. Euler's argument shows that a necessary condition for the walk of the desired form is that the graph be connected and have exactly zero or two nodes of odd degree. This condition turns out also to be sufficient—a result stated by Euler and later proven by Carl Hierholzer. Such a walk is now called an Eulerian path or Euler walk in his honor. Further, if there are nodes of odd degree, then any Eulerian path will start at one of them and end at the other. Since the graph corresponding to historical Königsberg has four nodes of odd degree, it cannot have an Eulerian path.

An alternative form of the problem asks for a path that traverses all bridges and also has the same starting and ending point. Such a walk is called an Eulerian circuit or an Euler tour. Such a circuit exists if, and only if, the graph is connected, and there are no nodes of odd degree at all. All Eulerian circuits are also Eulerian paths, but not all Eulerian paths are Eulerian circuits.

Euler's work was presented to the St. Petersburg Academy on 26 August 1735, and published as Solutio problematis ad geometriam situs pertinentis (The solution of a problem relating to the geometry of position) in the journal Commentarii academiae scientiarum Petropolitanae in 1741.[2] It is available in English in The World of Mathematics.

Significance in the history of mathematics

In the history of mathematics, Euler's solution of the Königsberg bridge problem is considered to be the first theorem of graph theory and the first true proof in the theory of networks,[3] a subject now generally regarded as a branch of combinatorics. Combinatorial problems of other types had been considered since antiquity.

In addition, Euler's recognition that the key information was the number of bridges and the list of their endpoints (rather than their exact positions) presaged the development of topology. The difference between the actual layout and the graph schematic is a good example of the idea that topology is not concerned with the rigid shape of objects.

Variations

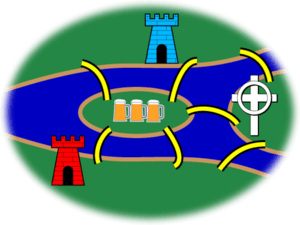

The classic statement of the problem, given above, uses unidentified nodes—that is, they are all alike except for the way in which they are connected. There is a variation in which the nodes are identified—each node is given a unique name or color.

The northern bank of the river is occupied by the Schloß, or castle, of the Blue Prince; the southern by that of the Red Prince. The east bank is home to the Bishop's Kirche, or church; and on the small island in the center is a Gasthaus, or inn.

It is understood that the problems to follow should be taken in order, and begin with a statement of the original problem:

It being customary among the townsmen, after some hours in the Gasthaus, to attempt to walk the bridges, many have returned for more refreshment claiming success. However, none have been able to repeat the feat by the light of day.

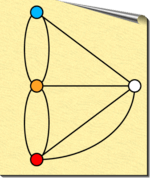

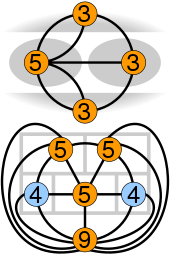

Bridge 8: The Blue Prince, having analyzed the town's bridge system by means of graph theory, concludes that the bridges cannot be walked. He contrives a stealthy plan to build an eighth bridge so that he can begin in the evening at his Schloß, walk the bridges, and end at the Gasthaus to brag of his victory. Of course, he wants the Red Prince to be unable to duplicate the feat from the Red Castle. Where does the Blue Prince build the eighth bridge?

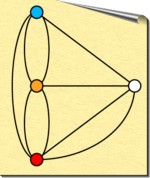

Bridge 9: The Red Prince, infuriated by his brother's Gordian solution to the problem, wants to build a ninth bridge, enabling him to begin at his Schloß, walk the bridges, and end at the Gasthaus to rub dirt in his brother's face. As an extra bit of revenge, his brother should then no longer be able to walk the bridges starting at his Schloß and ending at the Gasthaus as before. Where does the Red Prince build the ninth bridge?

Bridge 10: The Bishop has watched this furious bridge-building with dismay. It upsets the town's Weltanschauung and, worse, contributes to excessive drunkenness. He wants to build a tenth bridge that allows all the inhabitants to walk the bridges and return to their own beds. Where does the Bishop build the tenth bridge?

Solutions

Reduce the city, as before, to a graph. Color each node. As in the classic problem, no Euler walk is possible; coloring does not affect this. All four nodes have an odd number of edges.

Bridge 8: Euler walks are possible if exactly zero or two nodes have an odd number of edges. If we have 2 nodes with an odd number of edges, the walk must begin at one such node and end at the other. Since there are only 4 nodes in the puzzle, the solution is simple. The walk desired must begin at the blue node and end at the orange node. Thus, a new edge is drawn between the other two nodes. Since they each formerly had an odd number of edges, they must now have an even number of edges, fulfilling all conditions. This is a change in parity from an odd to even degree.

Bridge 9: The 9th bridge is easy once the 8th is solved. The desire is to enable the red castle and forbid the blue castle as a starting point; the orange node remains the end of the walk and the white node is unaffected. To change the parity of both red and blue nodes, draw a new edge between them.

Bridge 10: The 10th bridge takes us in a slightly different direction. The Bishop wishes every citizen to return to his starting point. This is an Euler circuit and requires that all nodes be of even degree. After the solution of the 9th bridge, the red and the orange nodes have odd degree, so their parity must be changed by adding a new edge between them.

Present state of the bridges

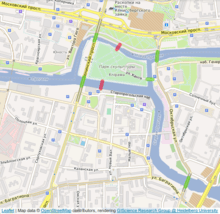

Two of the seven original bridges did not survive the bombing of Königsberg in World War II. Two others were later demolished and replaced by a modern highway. The three other bridges remain, although only two of them are from Euler's time (one was rebuilt in 1935).[4] Thus, as of 2000, there are five bridges in Kaliningrad that were a part of the Euler's problem.

In terms of graph theory, two of the nodes now have degree 2, and the other two have degree 3. Therefore, an Eulerian path is now possible, but it must begin on one island and end on the other.[5]

Canterbury University in Christchurch, New Zealand, has incorporated a model of the bridges into a grass area between the old Physical Sciences Library and the Erskine Building, housing the Departments of Mathematics, Statistics and Computer Science.[6] The rivers are replaced with short bushes and the central island sports a stone tōrō. Rochester Institute of Technology has incorporated the puzzle into the pavement in front of the Gene Polisseni Center, an ice hockey arena that opened in 2014.[7]

See also

- Eulerian path

- Five room puzzle

- Glossary of graph theory

- Hamiltonian path

- Icosian game

- Water, gas, and electricity

References

- ↑ See Shields, Rob (December 2012). 'Cultural Topology: The Seven Bridges of Königsburg 1736' in Theory Culture and Society 29. pp.43-57 and in versions online for a discussion of the social significance of Euler's engagement with this popular problem and its significance as an example of (proto-)topological understanding applied to everyday life.

- ↑ The Euler Archive, commentary on publication, and original text, in Latin.

- ↑ Newman, M. E. J. The structure and function of complex networks (PDF). Department of Physics, University of Michigan.

- ↑ Taylor, Peter (December 2000). "What Ever Happened to Those Bridges?". Australian Mathematics Trust. Archived from the original on 19 March 2012. Retrieved 11 November 2006.

- ↑ Stallmann, Matthias (July 2006). "The 7/5 Bridges of Koenigsberg/Kaliningrad". Retrieved 11 November 2006.

- ↑ "About – Mathematics and Statistics – University of Canterbury". math.canterbury.ac.nz. Retrieved 4 November 2010.

- ↑ https://twitter.com/ritwhky/status/501529429185945600

External links

- Kaliningrad and the Konigsberg Bridge Problem at Convergence

- Euler's original publication (in Latin)

- The Bridges of Königsberg

- How the bridges of Königsberg help to understand the brain

- Euler's Königsberg's Bridges Problem at Math Dept. Contra Costa College

- Pregel – A Google graphing tool named after this problem

- The count of Königsberg, short story about love and loss, set between the bridges of Königsberg

Coordinates: 54°42′12″N 20°30′56″E / 54.70333°N 20.51556°E