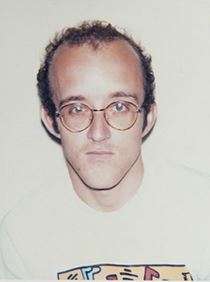

Keith Haring

| Keith Haring | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born |

Keith Allen Haring May 4, 1958 Reading, Pennsylvania |

| Died |

February 16, 1990 (aged 31) New York City, New York |

| Education |

The Ivy School of Professional Art (Pittsburgh) School of Visual Arts (New York) |

| Known for | Pop art, graffiti art |

| Notable work | "Crack is Wack" |

| Movement | AIDS awareness |

| Awards | The Art Award |

| Website |

haring |

Keith Allen Haring (May 4, 1958 – February 16, 1990) was an American artist and social activist whose work responded to the New York City street culture of the 1980s by expressing concepts of birth, death, sexuality, and war.[1]

Haring's work was often heavily political[2] and his imagery has become a widely recognized visual language of the 20th century.[3]

Early life and education

Keith Haring was born in Reading, Pennsylvania, on May 4, 1958. He was raised in Kutztown, Pennsylvania, by his mother Joan Haring, and father Allen Haring, an engineer and amateur cartoonist. He had three younger sisters, Kay, Karen and Kristen.[4] Haring became interested in art at a very early age spending time with his father producing creative drawings.[5] His early influences included Walt Disney cartoons, Dr. Seuss, Charles Schulz, and the Looney Tunes characters in The Bugs Bunny Show.[5] He studied commercial art from 1976 to 1978 at Pittsburgh's Ivy School of Professional Art but lost interest in it.[6] He made this decision having read Robert Henri's The Art Spirit (1923) which inspired him to concentrate on his own art.[5]

Haring had a maintenance job at the Pittsburgh Center for the Arts and was able to explore the art of Jean Dubuffet, Jackson Pollock, and Mark Tobey. His most critical influences at this time were a 1977 retrospective of the work of Pierre Alechinsky and a lecture by the sculptor Christo in 1978. Alechinsky's work, connected to the international Expressionist group CoBrA, gave Haring confidence to create larger paintings of calligraphic images. Christo introduced him to the possibilities of involving the public with his art. Haring's first important one-man exhibition was in Pittsburgh at the Center for the Arts in 1978.[5]

He moved to New York to study painting at the School of Visual Arts. He studied semiotics with Bill Beckley as well as exploring the possibilities of video and performance art. Profoundly influenced at this time by the writings of William Burroughs, he was inspired to experiment with the cross-referencing and interconnection of images.[5] In his junior/senior year, he was behind on credits, because his professors could not give him credit for the very loose artwork he was doing with themes of social activism.

Career

Early work

He first received public attention with his public art in subways. Starting in 1980, he organized exhibitions at Club 57,[7] which were filmed by the photographer Tseng Kwong Chi. Around this time, "The Radiant Baby" became his symbol. His bold lines, vivid colors, and active figures carry strong messages of life and unity.[7] He participated in the Times Square Exhibition and drew animals and human faces for the first time. That same year, he photocopied and pasted provocative collages made from cut-up and recombined New York Post headlines around the city.[8] In 1981, he sketched his first chalk drawings on black paper and painted plastic, metal, and found objects.

By 1982, Haring had established friendships with fellow emerging artists Futura 2000, Kenny Scharf, Madonna and Jean-Michel Basquiat.[7] He created more than 50 public works between 1982 and 1989 in dozens of cities around the world.[6] His "Crack is Wack" mural, created in 1986, is visible from New York's FDR Drive.[6] He got to know Andy Warhol, who was the theme of several of Haring's pieces, including "Andy Mouse". His friendship with Warhol would prove to be a decisive element in his eventual success.[7]

In December 2007, an area of the American Textile Building in the TriBeCa neighborhood of New York City was discovered to contain a painting of Haring's from 1979.[9]

International breakthrough

In 1984, Haring visited Australia and painted wall murals in Melbourne (such as the 1984 'Detail-Mural at Collingwood College, Victoria') and Sydney and received a commission from the National Gallery of Victoria and the Australian Centre for Contemporary Art to create a mural which temporarily replaced the water curtain at the National Gallery.[10] He also visited and painted in Rio de Janeiro, the Musée d'Art Moderne de la Ville de Paris, Minneapolis and Manhattan.[7] He became politically active, designing a Free South Africa poster in 1985, and in 1986, painting a section of the Berlin Wall. He was interested in working with children and this inspired the project Citykids Speak on Liberty, which involved 1,000 children collaborating on a project for the centennial of the Statue of Liberty.[5]

When asked about the commercialism of his work, Haring said: "I could earn more money if I just painted a few things and jacked up the price. My shop is an extension of what I was doing in the subway stations, breaking down the barriers between high and low art."[11] By the arrival of Pop Shop, his work began reflecting more socio-political themes, such as anti-Apartheid, AIDS awareness, and the crack cocaine epidemic. He even created several pop art pieces influenced by other products: Absolut Vodka, Lucky Strike cigarettes, and Coca-Cola.[7] In 1987 he had his own exhibitions in Helsinki, Antwerp, and elsewhere. He also designed the cover for the benefit album A Very Special Christmas, on which Madonna was included. In 1988 he joined a select group of artists whose work has appeared on the label of Chateau Mouton Rothschild wine.

Haring also created public murals in the lobby and ambulatory care department of Woodhull Medical and Mental Health Center on Flushing Avenue, Brooklyn.

A rare video of Haring at work[12] shows his energetic style. Haring wrote: "I am becoming much more aware of movement. The importance of movement is intensified when a painting becomes a performance. The performance (the act of painting) becomes as important as the resulting painting."

When his friend Jean-Michel Basquiat died of an overdose in New York in 1988, he paid homage to him with his work A Pile of Crowns, for Jean-Michel Basquiat.[13]

Haring was openly gay and was a strong advocate of safe sex;[14] however, in 1988, he was diagnosed with AIDS. In 1989, he established the Keith Haring Foundation to provide funding and imagery to AIDS organizations and children's programs, and to expand the audience for his work through exhibitions, publications and the licensing of his images. Haring used his imagery during the last years of his life to speak about his illness and to generate activism and awareness about AIDS.[6] In 1989, he was invited by the Lesbian and Gay Community Services Center to join a show of site-specific artwork for the building at 208 West 13th Street. Haring chose the second-floor men's room for his mural Once Upon a Time.[15] In June, on the rear wall of the convent of the Church of Sant'Antonio (in Italian: Chiesa di Sant'Antonio abate) in Pisa (Italy), he painted the last public work of his life, the mural "Tuttomondo" (translation: "All world").[7]

Fashion

Haring collaborated with Grace Jones, whom he had met through Andy Warhol. In 1985, Haring and Jones worked together on the two live performances Jones at the Paradise Garage, which Robert Farris Thompson has called a "epicenter for black dance". Each time, Haring covered Jones' body with graffiti. He also collaborated with fashion designers Vivienne Westwood and Malcolm McLaren on their A/W 1983/84 Witches collection, with his artwork covering the clothing which was most famously worn by a pink-wigged Madonna for a performance of her song "Like a Virgin" on the British pop-music programme Top of the Pops and the American TV dance program Solid Gold.[7] Haring also collaborated with David Spada, a jewelry designer, to design the sculptural adornments for Jones.[16]

Influences

Haring's work very clearly demonstrates many important political and personal influences. Ideas about his sexual orientation are apparent throughout his work and his journals clearly confirm its impact on his work. Heavy symbolism speaking about the AIDS epidemic is vivid in his later pieces, such as Untitled (cat. no. 27), Silence=Death and his sketch Weeping Woman. In some of his works—including cat. no. 27—the symbolism is subtle, but Haring also produced some blatantly activist works. Silence=Death is almost universally agreed upon as a work of HIV/AIDS activism.[17]

Sexuality

One of many consistent ideas, sexuality was a predominant theme throughout Haring's work. Through much of his art there are scenes of penetration, in a bodily and sexual sense. These scenes are often filled with monsters, skeletons and beasts, which almost always add a nightmarish feeling to the work. Rather than being something positive or affirming, sexuality is almost always presented as threatening or silence. "Rape, sexual compulsion and castration are the fundamental forms in which individual self-determination is forcibly prevented."[17] For Haring, sex was part of his work because it was part of his life. "It's inevitable that the subway drawings have it too because it's part of my life and part of the rest of the body of work," he said.[18] Haring's perception of sex was later affected by constant fear as the threat of AIDS became apparent.

It is possible that the drama in Haring's work demonstrates the stigma associated with homosexual relationships, in particular male-male relationships. Because all of the sexual acts portrayed were shown as being experienced illicitly, Haring felt they would always "carry with them the feeling of guilt with which they were imagined, portrayed and executed".[17] Haring was one of the first to present homosexuality in a politically progressive way. Because of that, almost – not in spite of it – the then-inevitable link between homosexual sexual activity and AIDS is apparent in Haring's later works.[17]

The possible messages that can be identified in this painting have more power when the viewer takes into account Haring's aim of being sexually progressive in his work, and progressive on behalf of the homosexual community. Cultural views toward homosexuality, especially as they existed then, add a layer of guilt and loss to Haring's paintings. Haring's aim, in many ways, was to move sexuality (and specifically homosexuality) away from the subculture and stereotypes. With the rise of AIDS, Haring aimed to turn the message about the disease outward by presenting it through the joint lenses of political power, religious institutionalism, and anti-sexual morals.[17]

AIDS

The theme of AIDS permeates Haring's late work, most likely because it had a heavy influence on his personal life. Midway through Haring's journals there is mention of the disease claiming his friends' lives, and later passages show Haring worrying increasingly about his own HIV status. For Haring, the fear was based in watching his friends die, not in his own fragility. On March 20, 1987, Haring wrote, "I'm scared of having to watch more people die in front of me...I refuse to die like that. If the time comes, I think suicide is much more dignified and much easier on friends and loved ones. Nobody deserves to watch this kind of slow death."[19] Haring avoided diagnosis for many years, but he felt it coming even then, and the impending diagnosis drove his work. "The odds are very great and, in fact, the symptoms already exist," he wrote in 1987. "I know in my heart that is only divine intervention that has kept me alive this long. I don't know if I have five months or five years, but I know my days are numbered. This is why my activities and projects are so important now. To do as much as possible as quickly as possible."[19]

When looking at Haring's work post-1988, after his diagnosis, the focus seems to be primarily on male sexuality. The odd, foreboding symbol of the horned sperm begins to arise in much of his work, and this figure has been regarded as his personification of the AIDS virus. Perhaps the most representative example of Haring's post-AIDS work is the large scale work cat no. 27. The piece features a large, horned sperm, drawn in white on a black background. The symbol was meant to embody everything that had become real in Haring's life: death as a result of physical love, or a deathly threat to sexuality. The horned sperm is shown hatching from an egg strapped to an individual's back. At the time of Haring's diagnosis, AIDS was nowhere near acceptance, and it was very much viewed through the prism of homophobia. "The discussion of AIDS as a 'gay cancer' and a 'divine punishment' for indecent living in the eighties was the subject of heated debate."[17] Haring highlighted homophobia, and the corresponding AIDS-phobia, in his journal entries on many occasions, but there came a point when it no longer surprised him. "Read yet another AIDS article in the Herald Tribune," he wrote. "Article about homophobia increase on American college campuses. Violence, etc. Very frightening, but very predictable."[19]

The symbolism in Haring's work bears the weight of this oppression. The burden of the egg in cat. no. 27 could be seen to represent the oppressive effects AIDS had brought on the individuals dealing with the disease. The idea of anonymous sex was becoming more and more taboo in the homosexual community and the community was facing more and more discrimination as people reacted in fear to the AIDS epidemic. Haring states in his diary that he wanted danger declared, that he had to call it off, as does everyone else: "There really can't be any more anonymous sex." He probes into the horror that could result from extreme promiscuity at the height of the AIDS epidemic; talking about individuals who have literally "fucked themselves to death". Haring was conflicted about his dark perceptions of sex, but they persisted nonetheless. "Maybe I don't have any right to complain," he wrote. "I've had an incredible life and had enough sex in ten years for an entire lifetime, but it doesn't work like that. It's not a rational thing that can be explained away."[19]

In his work Silence=Death Haring portrays multiple figures covering their eyes, mouths, and ears. The piece is intended to illustrate the oppression and invisibility that AIDS victims felt in the 1980s. Works like Haring's helped to give those living with AIDS more visibility at a time when many were suffering in absolute silence, with no voice, no visibility and no support from those around them. In Silence=Death, the figures are all laid over a pink triangle, a symbol associated with homosexual men. Originally used during the Holocaust, the pink triangle was used to signify those who were being targeted for their homosexuality. Since then, the symbol has often been reclaimed and re-appropriated by the gay rights movement. The AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power (ACT UP) also used the symbol starting in 1987.

AIDS diagnosis

In July 1987, Haring visited an AIDS specialist. On May 1, 1987, he mentioned in his journal rumors that were circulating throughout the art community about his AIDS status. He wrote that his friend Tony was "still worried because the Art World gossip hotline still says I have AIDS... If anything causes me tension and stress it's him, not staying up late or working hard. I live for work."[19]

Haring's diagnosis was never a secret; it was public knowledge and an accepted part of his persona in the media. Those publicly shared thoughts were reflected, often with more depth, in his work. Despite all the fear that led up to diagnosis, in some ways Haring found his impending death liberating. It pushed him to produce more work as quickly as possible. In a 1989 interview with Rolling Stone magazine, Haring stated, "That's the point that I am at now, not knowing where it stops but knowing how important it is to do it now. The whole thing is getting more articulate. In a way it's really liberating."[18] Critics have recognized this about Haring's works – particularly his later works – as well. "Haring's way of living life – liberated and with death in mind at a young age – allowed him to pull himself away from his diagnosis," Blinderman writes. "A year after his original diagnosis he was producing radiant paintings of birth and life." The introduction to the compilation of Haring's journals sings the same song: "Haring accepts his death. For in his art he found the key to transform desire, the force that killed him, into a flowering elegance that will live beyond his time."[19]

Death

Haring died on February 16, 1990 of AIDS-related complications.[20]

As a celebration of his life, Madonna declared the first New York date of her Blond Ambition World Tour a benefit concert for Haring's memory and donated all proceeds from her ticket sales to AIDS charities including AIDS Project Los Angeles and amfAR; the act was documented in her film Truth or Dare. Additionally, Haring's work was featured in several of Red Hot Organization's efforts to raise money for AIDS and AIDS awareness, specifically its first two albums, Red Hot + Blue and Red Hot + Dance, the latter of which used Haring's work on its cover.

Exhibitions

Haring contributed to the New York New Wave display in 1981 and in 1982, and had his first exclusive exhibition in the Tony Shafrazi Gallery. That same year, he took part in Documenta 7 in Kassel, Germany, as well as Public Art Fund's "Messages to the Public" in which he created work for a Spectacolor Board in Times Square.[21] He contributed work to the Whitney Biennial in 1983, as well as in the São Paulo Biennial. In 1985, the CAPC in Bordeaux opened an exhibition of his works, and took part in the Paris Biennial.

Since his death Haring has been the subject of several international retrospectives. His art was the subject of a 1997 retrospective at the Whitney Museum in New York, curated by Elisabeth Sussman. In 1996, a retrospective at the Museum of Contemporary Art Australia was the first major exhibition of his work in Australia. In 2008 there was a retrospective exhibition at the MAC in Lyon, France. In February 2010, on occasion of the 20th anniversary of the artist's death, Tony Shafrazi Gallery showed an exhibition containing dozens of works from every stage of Haring's mature work.[22] In March 2012, a retrospective exhibit of Haring's work, Keith Haring: 1978-1982, opened at the Brooklyn Museum in New York.[23] In April 2013, Keith Haring: The Political Line opened at the Musee d'Art Moderne de la Ville de Paris and Le Cent Quatre In November 2014, then at the De Young Museum in San Francisco, California.[24]

Collections

Haring's work is in major private and public collections, including the Museum of Modern Art and the Whitney Museum of American Art, New York; Los Angeles County Museum of Art; the Art Institute of Chicago; the Bass Museum, Miami; Musée d'Art Moderne de la Ville de Paris; Ludwig Museum, Cologne; and Stedelijk Museum, Amsterdam.[25] Haring did a wide variety of public works, including the infirmary at Children's Village in Dobbs Ferry, New York,[26] and the second floor men's room in the Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual & Transgender Community Center in Manhattan, which was later transformed into an office and is known as the Keith Haring room.[27][28]

Art market

Haring was represented by dealer Tony Shafrazi until he died.[29] Since the artist's death in 1990, his estate has been administered by the Keith Haring Foundation. The foundation has a twofold mission of supporting educational opportunities for underprivileged children and financing AIDS research and patient care.[30] The foundation is represented by Gladstone Gallery.

Authentication issues

There is no catalogue raisonné for Haring; however, there is copious information about Haring available on the estate's website and elsewhere, enabling prospective buyers or sellers to research exhibition history.[31] In 2012, the Keith Haring Foundation disbanded its authentication board; that same year, it donated $1 million to support exhibitions at the Whitney Museum of American Art[29] and $1 million to Planned Parenthood of New York City's Project Street Beat. A 2014 lawsuit, filed by a group of nine art collectors at the United States District Court for the Southern District of New York, argued that the Keith Haring Foundation's actions have "limited the number of Haring works in the public domain, thereby increasing the value of the Haring works that the foundation and its members own or sell."[32]

In popular culture

Haring is the subject of a composition, Haring at the Exhibition, written and performed by Italian composer Lorenzo Ferrero in collaboration with DJ Nicola Guiducci. The work combines excerpts from popular chart music of the 1980s with samples of classical music compositions by Lorenzo Ferrero and synthesized sounds. It was featured at "The Keith Haring Show",[33] an exhibition which took place in 2005 at the Triennale di Milano.

In 2006, Keith Haring was named by Equality Forum as one of their 31 Icons of the LGBT History Month.[34]

In 2008, filmmaker Christina Clausen released the documentary The Universe of Keith Haring. In the film, the legacy of Haring is resurrected through colorful archival footage and remembered by friends and admirers such as artists Kenny Scharf and Yoko Ono, gallery owners Jeffrey Deitch and Tony Shafrazi, and the choreographer Bill T. Jones.[35]

Madonna, who was friends with Haring during the 1980s, used his art as animated backdrops for her 2008/2009 Sticky and Sweet Tour. The animation is standard Haring featuring his trademark blocky figures dancing in beat to an updated remix of "Into the Groove".[36]

Keith Haring: Double Retrospect is a monster sized jigsaw puzzle by Ravensburger measuring in at 17' x 6' with 32,256 pieces, breaking Guinness Book of World Records for the largest puzzle ever made. The puzzle uses 32 pieces of work from Haring and weighs 42 pounds.[37]

On May 4, 2012, on what would have been Haring's 54th birthday, Google honored him in a Google Doodle.[38]

Haring designed the album cover for the A Very Special Christmas music compilation album which consists of a typical Haring figure holding a baby. Its "Jesus iconography " is considered unusual in modern rock holiday albums.[39]

Haring had a balloon in tribute to him at the Macy's Thanksgiving Day Parade. The balloon slammed into the NBC broadcast booth during the 2008 parade, and the program went off the air for a moment.[40]

See also

References

- ↑ John Gruen (1992), Keith Haring: The Authorized Biography, Simon and Schuster, p. 1952, ISBN 9780671781507

- ↑ Holmes, Julia (2002-10-01). 100 New Yorkers: A Guide To Illustrious Lives & Locations. Little Bookroom. pp. 99–. ISBN 9781892145314. Retrieved 7 September 2014.

- ↑ Haggerty, George (2013-11-05). Encyclopedia of Gay Histories and Cultures. Taylor & Francis. pp. 425–. ISBN 9781135585136. Retrieved 7 September 2014.

- ↑ http://www.haring.com/!/about-haring

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 "Keith Haring". encyclopedia.com. High Beam Research. Retrieved 19 July 2015.

- 1 2 3 4 "Bio (archived)". The Keith Haring Foundation. Archived from the original on September 9, 2013. Retrieved 12 June 2014.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 "Keith Haring Street Artist Biography". stencilrevolution.com. Stencil Revolution. Retrieved 17 July 2015.

- ↑ Karen Rosenberg (March 22, 2012), A Pop Shop for a New Generation The New York Times.

- ↑ Hope, Bradley (December 20, 2007). "A Forgotten Haring Is Found by Contractors". The New York Sun. Retrieved December 20, 2007.

- ↑ Ellis, Rennie, The New Australian Graffiti, (Sun Books Melbourne, 1985)

- ↑ Yarrow, Andrew (February 17, 1990). "Keith Haring, Artist, Dies at 31; Career Began in Subway Graffiti". The New York Times. Retrieved May 25, 2010.

- ↑ "From the archives: Keith Haring was here". CBS Sunday Morning. Retrieved April 18, 2016.

- ↑ Thompson, Robert Farris (May 1990). "Requiem for the Degas of the B-boys". Haring.com. Art Forum. Retrieved 17 August 2016.

- ↑ Sheff, David (August 10, 1989). "Keith Haring: Just Say Know". Rolling Stone. Retrieved November 14, 2007.

- ↑ David W. Dunlap (March 7, 2012), A Joyous Mural, Born In an Era Filled With Fear The New York Times.

- ↑ Kershaw, Miriam (Winter 1997). "Post-colonialism and Androgyny: The Performance Art of Grace Jones". Performance Art: (Some) Theory and (Selected) Practice at the End of this Century, pp19-25.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Haring, Keith, Götz Adriani, and Ralph Melcher. Keith Haring: Heaven and Hell. Ostfildern-Ruit, Germany: Hatje Cantz, 2001. Print.

- 1 2 Haring, Keith. Barry Blinderman. Keith Haring: Future Primeval. Normal, Ill: University Galleries, Illinois State University, 1991. Print.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Haring, Keith. Keith Haring Journals. New York: Viking, 1996. Print.

- ↑ "JOY broadcasts Haring mural anniversary - Gay News Network". Retrieved 2014-03-07.

- ↑ "Keith Haring Biography". famouspeople.com. Famous People. Retrieved 19 July 2015.

- ↑ Vartanian, Hrag (April 2010). "Keith Haring: 20th Anniversary". The Brooklyn Rail.

- ↑ "Exhibitions: Keith Haring: 1978–1982", Brooklyn Museum, New York, March 16 – July 8, 2012. Reviewed: Ted Loos (June 17, 2012). "In Code: Spaceships, Babies, Evil TVs". The New York Times.

- ↑ https://deyoung.famsf.org/press-room/keith-haring-political-line

- ↑ Keith Haring, May 4 - July 1, 2011 Gladstone Gallery

- ↑ Haring, Keith. "Existing Public Works Children's Village 1984". Haring.com. Keith Haring Foundation. Retrieved 23 May 2015.

- ↑ Haring, Keith. "Existing Public Works Once Upon a Time, 1989". Haring.com. Keith Haring Foundation. Retrieved 23 May 2015.

- ↑ "Existing Public Works Once Upon a Time, 1989". Gay Center. The Center. Retrieved 23 May 2015.

- 1 2 Rachel Corbett (November 7, 2012), Is Keith Haring Undervalued? Insiders Bet Big on a "Correction" in His Market

- ↑ Kate Deimling (November 8, 2010), Keith Haring Estate Joins Barbara Gladstone Gallery

- ↑ Charlotte Burns (October 12, 2012), Haring market in turmoil - Prolific artist's foundation is latest to close its authentication board, The Art Newspaper.

- ↑ Benjamin Weiser (February 21, 2014), Collectors of Keith Haring Works File Lawsuit The New York Times.

- ↑ The Keith Haring Show, 2005–2006, Milan

- ↑ http://www.lgbthistorymonth.com/keith-haring?tab=biography

- ↑ Lee, Nathan (October 24, 2008). "An Artist With Enthusiasm". The New York Times.

- ↑ Watch Madonna's "Into the Groove" Keith Haring Tour Backdrop Animation

- ↑ Morgan, Matt (February 11, 2011). "Ravensburger Shatters Record With 32,000+ piece puzzle". Wired.

- ↑ Gruen, Julia (May 4, 2012). "Keith Haring's 54th Birthday". Google. Retrieved May 6, 2012.

- ↑ Santino, Jack (1996). New Old-fashioned Ways: Holidays and Popular Culture. Univ. of Tennessee Press. pp. 51–. ISBN 9780870499524. Retrieved 20 September 2014.

- ↑ "Top 10 Macy's Thanksgiving Day Parade Balloon Accidents". Philips Law Group. November 26, 2013.

Further reading

- Phillips, Natalie E., "The Radiant (Christ) Child: Keith Haring and the Jesus Movement", American Art, Vol. 21, No. 3 (Fall 2007), pp. 54–73. The University of Chicago Press

- Reading Public Museum, Keith Haring: Journey of the Radiant Baby, Piermont, N.H. : Bunker Hill Publishing Co., 2006. ISBN 978-1593730529

- Van Pee, Yasmine. Boredom is always counterrevolutionary: art in downtown New York nightclubs, 1978-1985 (M.A. thesis, Center for Curatorial Studies at Bard College, 2004).

External links

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Keith Haring |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Keith Haring. |