Khmer numerals

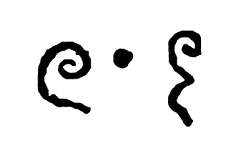

Khmer numerals are the numerals used in the Khmer language. They have been in use since at least the early 7th century, with the earliest known use being on a stele dated to AD 604 found in Prasat Bayang, Cambodia, near Angkor Borei.[2][3]

Numerals

| Numeral systems |

|---|

|

| Hindu–Arabic numeral system |

| East Asian |

| Alphabetic |

| Former |

| Positional systems by base |

| Non-standard positional numeral systems |

| List of numeral systems |

Having been derived from the Hindu numerals, modern Khmer numerals also represent a decimal positional notation system. It is the script with the first extant material evidence of zero as a numerical figure, dating its use back to the seventh century, two centuries before its certain use in India.[2][4] However, Old Khmer, or Angkorian Khmer, also possessed separate symbols for the numbers 10, 20, and 100. Each multiple of 20 or 100 would require an additional stroke over the character, so the number 47 was constructed using the 20 symbol with an additional upper stroke, followed by the symbol for number 7.[5] This inconsistency with its decimal system suggests that spoken Angkorian Khmer used a vigesimal system.

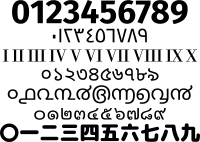

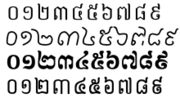

As both Thai and Lao scripts are derived from Old Khmer,[6] their modern forms still bear many resemblances to the latter, demonstrated in the following table:

| Value | Khmer | Thai | Lao |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | ០ | ๐ | ໐ |

| 1 | ១ | ๑ | ໑ |

| 2 | ២ | ๒ | ໒ |

| 3 | ៣ | ๓ | ໓ |

| 4 | ៤ | ๔ | ໔ |

| 5 | ៥ | ๕ | ໕ |

| 6 | ៦ | ๖ | ໖ |

| 7 | ៧ | ๗ | ໗ |

| 8 | ៨ | ๘ | ໘ |

| 9 | ៩ | ๙ | ໙ |

Modern Khmer numbers

The spoken names of modern Khmer numbers represent a biquinary system, with both base 5 and base 10 in use. For example, 6 (ប្រាំមួយ) is formed from 5 (ប្រាំ) plus 1 (មួយ).

Numbers from 0 to 5

With the exception of the number 0, which stems from Sanskrit, the etymology of the Khmer numbers from 1 to 5 is of proto-Mon–Khmer origin.

| Value | Khmer | Word Form | IPA | UNGEGN | ALA-LC | Other | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | ០ | សូន្យ | soun | sony | sūny | soun | From Sanskrit śūnya |

| 1 | ១ | មួយ | muəj | muŏy | muay | mouy | Before a classifier, /muəj/ is reduced to /mə/ in regular speech.[7] |

| 2 | ២ | ពីរ | piː (pɨl) | pir | bīr | pii | Also /pir/ |

| 3 | ៣ | បី | ɓəj | bei | pī | bei | |

| 4 | ៤ | បួន | ɓuən | buŏn | puan | buon | |

| 5 | ៥ | ប្រាំ | pram | prăm | prâṃ | pram |

- For details of the various alternative romanization systems, see Romanization of Khmer.

- Some authors may alternatively mark [ɓiː] as the pronunciation for the word two, and either [bəj] or [bei] for the word three.

- In neighbouring Thailand the number three is thought to bring good luck.[8] However, in Cambodia, taking a picture with three people in it is considered bad luck, as it is believed that the person situated in the middle will die an early death.[9][10]

Numbers from 6 to 20

As mentioned above, the numbers from 6 to 9 may be constructed by adding any number between 1 and 4 to the base number 5 (ប្រាំ), so that 7 is literally constructed as 5 plus 2. Beyond that, Khmer uses a decimal base, so that 14 is constructed as 10 plus 4, rather than 2 times 5 plus 4; and 16 is constructed as 10+5+1.

Colloquially, compound numbers from eleven to nineteen may be formed using the word ដណ្ដប់ [dɔnɗɑp] preceded by any number from one to nine, so that 15 is constructed as ប្រាំដណ្ដប់ [pram dɔnɗɑp], instead of the standard ដប់ប្រាំ [ɗɑp pram].[11]

| Value | Khmer | Word Form | IPA | UNGEGN | ALA-LC | Other | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 6 | ៦ | ប្រាំមួយ | pram muəj | prăm muŏy | prâṃ muay | pram muoy | |

| 7 | ៧ | ប្រាំពីរ | pram piː (pram pɨl) | prăm pir | prâṃ bīr | pram pii | |

| 8 | ៨ | ប្រាំបី | pram ɓəj | prăm bey | prâṃ pī | pram bei | |

| 9 | ៩ | ប្រាំបួន | pram ɓuən | prăm buŏn | prâṃ puan | pram buon | |

| 10 | ១០ | ដប់ | ɗɑp | dáb | ṭáp | dap | Old Chinese *di̯əp.[12] |

| 11 | ១១ | ដប់មួយ | ɗɑp muəj | dáb muŏy | ṭáp muay | dap muoy | Colloquially មួយដណ្ដប់ [muəj dɔnɗɑp]. |

| 20 | ២០ | ម្ភៃ | mpʰej (məpʰɨj, mpʰɨj) | mphey | mbhai | mpei | Contraction of /muəj/ + /pʰej/ (i.e. one + twenty) |

- In constructions from 6 to 9 that use 5 as a base, /pram/ may alternatively be pronounced [pəm]; giving [pəm muːəj], [pəm piː], [pəm ɓəj], and [pəm ɓuːən]. This is especially true in dialects which elide /r/, but not necessarily restricted to them, as the pattern also follows Khmer's minor syllable pattern.

Numbers from 30 to 90

The numbers from thirty to ninety in Khmer bear many resemblances to both the modern Thai and Cantonese numbers. It is likely that Khmer has borrowed them from the Thai language, as the numbers are both non-productive in Khmer (i.e. their use is restricted and cannot be used outside 30 to 90) and bear a near one-to-one phonological correspondence as can be observed in the language comparisons table below.

Informally, a speaker may choose to omit the final [səp] and the number is still understood. For example, it is possible to say [paət muəj] (ប៉ែតមួយ) instead of the full [paət səp muəj] (ប៉ែតសិបមួយ).

| Value | Khmer | Word Form | IPA | UNGEGN | ALA-LC | Other | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 30 | ៣០ | សាមសិប | saːm səp | sam sĕb | sām sip | sam sep | |

| 40 | ៤០ | សែសិប | sae sǝp | sê sĕb | sae sip | sae sep | |

| 50 | ៥០ | ហាសិប | haː səp | ha sĕb | hā sip | ha sep | |

| 60 | ៦០ | ហុកសិប | hok səp | hŏk sĕb | huk sip | hok sep | |

| 70 | ៧០ | ចិតសិប | cət səp | chĕt sĕb | cit sip | chet sep | |

| 80 | ៨០ | ប៉ែតសិប | paet səp | pêt sĕb | p″ait sip | paet sep | |

| 90 | ៩០ | កៅសិប | kaw səp | kau sĕb | kau sip | kao sep |

Language Comparisons:

| Value | Khmer | Thai | Archaic Thai | Lao | Cantonese | Teochew | Hokkien | Mandarin |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3 ‒ | *saːm | sam | sǎam | sãam | saam1 | sã1 | sa1 (sam1) | sān |

| 4 ‒ | *sɐe | si | sài | sii | sei3 | si3 | si3 (su3) | sì |

| 5 ‒ | *haː | ha | ngùa | hàa | ng5 | ŋou6 | go2 (ngo2) | wǔ |

| 6 ‒ | *hok | hok | lòk | hók | luk6 | lak8 | lak2 (liok8) | liù |

| 7 ‒ | *cət | chet | jèd | jét | cat1 | tsʰik4 | chit2 | qī |

| 8 ‒ | *pɐət | paet | pàed | pàet | baat3 | poiʔ4 | pueh4 (pat4) | bā |

| 9 ‒ | *kaw | kao | jao | kâo | gau2 | kao2 | kau4 (kiu2) | jiǔ |

| 10 ‒ | *səp | sip | jǒng | síp | sap6 | tsap8 | tzhap2 (sip8) | shí |

- Words in parenthesis indicate literary pronunciations, while words preceded with an asterisk mark are non-productive (i.e. only occur in specific constructions, but cannot be decomposed to form basic numbers).

Numbers from 100 to 10,000,000

The standard Khmer numbers starting from one hundred are as follows:

| Value | Khmer | Word Form | IPA | UNGEGN | ALA-LC | Other | Notes[13] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 100 | ១០០ | មួយរយ | muəj rɔːj (rɔːj, mərɔːj) | muŏy rôy | muay ray | muoy roy | Borrowed from Thai ร้อย roi. |

| 1 000 | ១០០០ | មួយពាន់ | muəj poan | muŏy poăn | muay bân | muoy poan | From Thai พัน phan. |

| 10 000 | ១០០០០ | មួយម៉ឺន | muəj məɨn | muŏy mœŭn | muay muȳn | muoy muen | From Thai หมื่น muen. |

| 100 000 | ១០០០០០ | មួយសែន | muəj saen | muŏy sên | muay s″ain | muoy saen | From Thai แสน saen. |

| 1 000 000 | ១០០០០០០ | មួយលាន | muəj lien | muŏy leăn | muay lân | muoy lean | From Thai ล้าน lan. |

| 10 000 000 | ១០០០០០០០ | មួយកោដិ | muəj kaot | muŏy kaôdĕ | muay koṭi | muoy kaot | From Sanskrit and Pali koṭi. |

Although [muəj kaot] មួយកោដិ is most commonly used to mean ten million, in some areas this is also colloquially used to refer to one billion (which is more properly [muəj rɔj kaot] មួយរយកោដិ). In order to avoid confusion, sometimes [ɗɑp liːən] ដប់លាន is used to mean ten million, along with [muəj rɔj liːən] មួយរយលាន for one hundred million, and [muəj poan liːən] មួយពាន់លាន ("one thousand million") to mean one billion.[14]

Different Cambodian dialects may also employ different base number constructions to form greater numbers above one thousand. A few of the such can be observed in the following table:

| Value | Khmer | Word Form[14][15] | IPA | UNGEGN | ALA-LC | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 10 000 | ១០០០០ | ដប់ពាន់ | ɗɑp poan | dáb poăn | ṭáp bân | Literally "ten thousand" |

| 100 000 | ១០០០០០ | ដប់ម៉ឺន | ɗɑp məɨn | dáb mœŭn | ṭáp muȳn | Literally "ten ten-thousand" |

| 100 000 | ១០០០០០ | មួយរយពាន់ | muəj rɔj poan | muŏy rôy poăn | muay ray bân | Literally "one hundred thousand" |

| 1 000 000 | ១០០០០០០ | មួយរយម៉ឺន | muəj rɔj məɨn | muŏy rôy mœŭn | muay ray muȳn | Literally "one hundred ten-thousand" |

| 10 000 000 | ១០០០០០០០ | ដប់លាន | ɗɑp lien | dáb leăn | ṭáp lân | Literally "ten million" |

| 100 000 000 | ១០០០០០០០០ | មួយរយលាន | muəj rɔj lien | muŏy rôy leăn | muay ray lân | Literally "one hundred million" |

| 1 000 000 000 | ១០០០០០០០០០ | មួយពាន់លាន | muəj poan lien | muŏy poăn leăn | muay ray bân | Literally "one thousand million" |

Counting fruits

Reminiscent of the standard 20-base Angkorian Khmer numbers, the modern Khmer language also possesses separate words used to count fruits, not unlike how English uses words such as a "dozen" for counting items such as eggs.[16]

| Value | Khmer | Word form | IPA | UNGEGN | ALA-LC | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 4 | ៤ | ដំប | dɑmbɑː | dâmbâ | ṭaṃpa | Also written ដំបរ (dâmbâr or ṭaṃpar) |

| 40 | ៤០ | ផ្លូន | ploːn | phlon | phlūn | From (pre-)Angkorian *plon "40" |

| 80 | ៨០ | ពីរផ្លូន | piː~pɨl ploːn | pir phlon | bir phlūn | Literally "two forty" |

| 400 | ៤០០ | ស្លឹក | slək | slœ̆k | slẏk | From (pre-)Angkorian *slik "400" |

Sanskrit and Pali influence

As a result of prolonged literary influence from both the Sanskrit and Pali languages, Khmer may occasionally use borrowed words for counting. Generally speaking, asides a few exceptions such as the numbers for 0 and 100 for which the Khmer language has no equivalent, they are more often restricted to literary, religious, and historical texts than they are used in day to day conversations. One reason for the decline of these numbers is that a Khmer nationalism movement, which emerged in the 1960s, attempted to remove all words of Sanskrit and Pali origin. The Khmer Rouge also attempted to cleanse the language by removing all words which were considered politically incorrect.[17]

| Value | Khmer | Word form | IPA | UNGEGN | ALA-LC | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 10 | ១០ | ទស | tʊəh | tôs | das | Sanskrit, Pali dasa |

| 12 | ១២ | ទ្វាទស | tvietʊəh tvieteaʔsaʔ | tvéatôs(â) | dvādas(a) | Sanskrit, Pali dvādasa |

| 13 or 30 | ១៣ or ៣០ | ត្រីទស | trəj tʊəh | trei tôs | trǐ das | Sanskrit, Pali trayodasa |

| 28 | ២៨ | អស្តាពីស | ʔahsdaː piː sɑː | ’asta pi sâ | qastā bǐ sa | Sanskrit (8, aṣṭá-) (20, vimsati) |

| 100 | ១០០ | សត | saʔtaʔ | sâtâ | sata | Sanskrit sata |

Ordinal numbers

Khmer ordinal numbers are formed by placing the word ទី [tiː] in front of a cardinal number.[18] This is similar to the use of ที่ thi in Thai, and thứ (from Chinese 第) in Vietnamese.

| Meaning | Khmer | IPA | UNGEGN | ALA-LC | Other | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| First | ទីមួយ | tiː muəj | ti muŏy | dī muay | ti muoy | |

| Second | ទីពីរ | tiː piː~pɨl | ti pir | dī bīr | ti pii | |

| Third | ទីបី | tiː ɓəj | ti bei | dī pī | ti bei |

Angkorian numbers

It is generally assumed that the Angkorian and pre-Angkorian numbers also represented a dual base (quinquavigesimal) system, with both base 5 and base 20 in use. Unlike modern Khmer, the decimal system was highly limited, with both the numbers for ten and one hundred being borrowed from the Chinese and Sanskrit languages respectively. Angkorian Khmer also used Sanskrit numbers for recording dates, sometimes mixing them with Khmer originals, a practice which has persisted until the last century.[19]

The numbers for twenty, forty, and four hundred may be followed by multiplying numbers, with additional digits added on at the end, so that 27 is constructed as twenty-one-seven, or 20×1+7.

| Value | Khmer | Orthography[5] | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | ១ | mvay | |

| 2 | ២ | vyar | |

| 3 | ៣ | pi | |

| 4 | ៤ | pvan | |

| 5 | ៥ | pram | (7 : pramvyar or pramvyal) |

| 10 | ១០ | tap | Old Chinese *di̯əp.[12] |

| 20 | ២០ | bhai | |

| 40 | ៤០ | plon | |

| 80 | ៨០ | bhai pvan | Literally "four twenty" |

| 100 | ១០០ | çata | Sanskrit (100, sata). |

| 400 | ៤០០ | slik |

Proto-Khmer numbers

Proto-Khmer is the hypothetical ancestor of the modern Khmer language bearing various reflexes of the proposed proto-Mon–Khmer language. By comparing both modern Khmer and Angkorian Khmer numbers to those of other Eastern Mon–Khmer (or Khmero-Vietic) languages such as Pearic, Proto-Viet–Muong, Katuic, and Bahnaric; it is possible to establish the following reconstructions for Proto-Khmer.[20]

Numbers from 5 to 10

Contrary to later forms of the Khmer numbers, Proto-Khmer possessed a single decimal number system. The numbers from one to five correspond to both the modern Khmer language and the proposed Mon–Khmer language, while the numbers from six to nine do not possess any modern remnants, with the number ten *kraaj (or *kraay) corresponding to the modern number for one hundred. It is likely that the initial *k, found in the numbers from six to ten, is a prefix.[20]

| Value | Khmer | Reconstruction[21][22] | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| 5 | ៥ | *pram | |

| 6 | ៦ | *krɔɔŋ | |

| 7 | ៧ | *knuul | |

| 8 | ៨ | *ktii | Same root as the word hand, *tii. |

| 9 | ៩ | *ksaar | |

| 10 | ១០ | *kraaj | Corresponds to present-day /rɔj/ (one hundred). |

References

- General

- David Smyth (1995). Colloquial Cambodian: A Complete Language Course. Routledge (UK). ISBN 0-415-10006-2.

- Huffman, Franklin E.; Charan Promchan; Chhom-Rak Thong Lambert (2008). "Huffman, Modern Spoken Cambodian". Retrieved 2008-03-25.

- Unknown (2005). Khmer Phrase Book: Everyday Phrases Mini-Dictionary.

- Smyth, David; Tran Kien (1998). Practical Cambodian Dictionary (2 ed.). Tuttle Language Library/Charles E. Tuttle Company. ISBN 0-8048-1954-8.

- Southeast Asia. Lonely Planet. 2006. ISBN 1-74104-632-7.

- "The original names for the Khmer tens: 30–90". 2008. Retrieved 2008-12-18.

|first1=missing|last1=in Authors list (help) - "SEAlang Library Khmer Lexicography". Retrieved 2008-12-07.

- "Veda:Sanskrit Numbers". Retrieved 2008-12-10.

- Specific

- ↑ Diller, Anthony (1996). "New Zeros and Old Khmer" (PDF). Australian National University. pp. 1–3. Retrieved 2009-01-11.

- 1 2 Eugene Smith, David; Louis Charles Karpinski (2004). The Hindu–Arabic Numerals. Courier Dover Publications. p. 39. ISBN 0-486-43913-5.

- ↑ Kumar Sharan, Mahesh (2003). Studies In Sanskrit Inscriptions Of Ancient Cambodia. Abhinav Publications. p. 293. ISBN 81-7017-006-0.

- ↑ Diller, Anthony (1996). New zeroes and Old Khmer (PDF). Australian National University.

- 1 2 Jacob, Judith M.; David Smyth. Cambodian Linguistics, Literature and History. Rootledge & University of London School of Oriental and African Studies. pp. 28–37. ISBN 0-7286-0218-0.

- ↑ "Khmer/Cambodian alphabet". Omniglot. 2008. Retrieved 2008-12-18.

- ↑ Ehrman, Madeline E.; Kem Sos (1972). Contemporary Cambodian: Grammatical Sketch. (PDF). Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office. p. 18.

- ↑ Asian Superstitions (PDF). ADB Magazine. June 2007.

- ↑ "Khmer superstition". 2008-03-01. Retrieved 2009-01-05.

- ↑ "Info on Cambodia". 2006. Retrieved 2009-01-05.

- ↑ Huffman, Franklin E. (1992). Cambodian System of Writing and Beginning Reader. SEAP Publications. pp. 58–59. ISBN 0-87727-520-3.

- 1 2 Gorgoniev, Yu A. (1961). Khmer language. p. 72.

- ↑ Jacob (1993). Notes on the numerals and numeral coefficients in Old, Middle, and Modern Khmer (PDF). p. 28.

- 1 2 "Khmer Numeral System". 2005-06-19. Retrieved 2008-12-18.

- ↑ "Spoken Khmer Number". 2003. Retrieved 2008-12-29.

- ↑ Thomas, David D. (1971). Chrau Grammar (Oceanic Linguistics Special Publications). No.7. University of Hawai'i Press. p. 236.

- ↑ "Khmer: Introduction". National Virtual Translation Center. 2007. Archived from the original on 2008-07-31. Retrieved 2008-12-18.

- ↑ "Khmer Cardinal Number". 2003. Retrieved 2008-12-18.

- ↑ Jacob, Judith M. "Mon–Khmer Studies VI: Sanskrit Loanwords in Pre-Angkorian Khmer" (PDF). School of Oriental and African Studies, University of London. Retrieved 2008-12-10.

- 1 2 Gvozdanović, Jadranka (1999). Numeral Types and Changes Worldwide. Walter de Gruyter. pp. 263–265. ISBN 3-11-016113-3.

- ↑ Jenner, Phillip N. (1976). Les noms de nombre en Khmer [The names of numbers in Khmer] (in French). 14. Mouton Publishers. p. 48. doi:10.1515/ling.1976.14.174.39. ISSN 1613-396X.

- ↑ Fisiak, Jacek (1997). Linguistic Reconstruction. Walter de Gruyter. p. 275. ISBN 3-11-014905-2.