Kishinev pogrom

- This article is part of the History of the Jews in Bessarabia.

The Kishinev pogroms were an anti-Jewish riot that took place in Kishinev, then the capital of the Bessarabia Governorate in the Russian Empire, on April 19 and 20, 1903, and a second, smaller riot that erupted in October 1905.

First pogrom

The most popular newspaper in Kishinev, the Russian-language anti-Semitic newspaper Бессарабец (Bessarabetz, meaning "Bessarabian"), published by Pavel Krushevan, regularly published articles with headlines such as "Death to the Jews!" and "Crusade against the Hated Race!" (referring to the Jews). When a Christian Ukrainian boy, Mikhail Rybachenko, was found murdered in the town of Dubossary, about 25 miles north of Kishinev, and a girl who committed suicide by poisoning herself was declared dead in a Jewish hospital, Bessarabetz insinuated that both children had been murdered by the Jewish community for the purpose of using their blood in the preparation of matzo for Passover.[1] Another newspaper, Свет (Svet, "Light") made similar insinuations. These allegations, and the prompting of the town's Russian Orthodox bishop, sparked the pogrom.

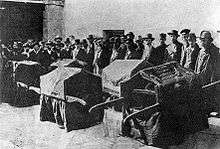

The pogrom began on April 19 (April 6 according to the Julian calendar then in use in the Russian empire) after congregations were dismissed from church services on Easter Sunday. In two days of rioting, 47 (some put the figure at 49) Jews were killed, 92 were severely wounded and 500 were slightly injured, 700 houses were destroyed, and 600 stores were pillaged.[2] The Times published a forged dispatch by Vyacheslav von Plehve, the Minister of Interior, to the governor of Bessarabia, which supposedly gave orders not to stop the rioters,[3] but, in any case, no attempt was made by the police or military to intervene to stop the riots until the third day.

The New York Times described the first Kishinev pogrom:

The anti-Jewish riots in Kishinev, Bessarabia, are worse than the censor will permit to publish. There was a well laid-out plan for the general massacre of Jews on the day following the Russian Easter. The mob was led by priests, and the general cry, "Kill the Jews," was taken- up all over the city. The Jews were taken wholly unaware and were slaughtered like sheep. The dead number 120 and the injured about 500. The scenes of horror attending this massacre are beyond description. Babes were literally torn to pieces by the frenzied and bloodthirsty mob. The local police made no attempt to check the reign of terror. At sunset the streets were piled with corpses and wounded. Those who could make their escape fled in terror, and the city is now practically deserted of Jews.[4]

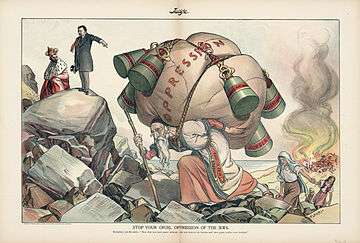

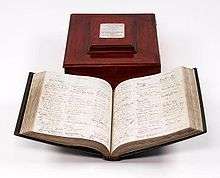

The Kishinev pogrom captured the attention of the international public and was mentioned in the Roosevelt Corollary to the Monroe Doctrine as an example of the type of human rights abuse which would justify United States involvement in Latin America. The 1904 book The Voice of America on Kishinev provides more detail[5] as does the book Russia at the Bar of the American people: A Memorial of Kishinef [6]

Second pogrom

A second pogrom took place on October 19–20, 1905. This time the riots began as political protests against the Tsar, but turned into an attack on Jews wherever they could be found. By the time the riots were over, 19 Jews had been killed and 56 were injured. Jewish self-defense leagues, organized after the first pogrom, stopped some of the violence, but were not wholly successful. This Pogrom was part of a much larger movement of 600 pogroms that swept the Russian Empire after the October Manifesto of 1905.

A Russian official's interpretation of events

The Russian ambassador to the United States, Count Arthur Cassini, characterised the first outbreak as a reaction of financially hard-pressed peasants to Jewish creditors in an interview on May 18, 1903:

There is in Russia, as in Germany and Austria, a feeling against certain of the Jews. The reason for this unfriendly attitude is found in the fact that the Jews will not work in the field or engage in agriculture. They prefer to be money lenders. ... The situation in Russia, so far as the Jews are concerned is just this: It is the peasant against the money lender, and not the Russians against the Jews. There is no feeling against the Jew in Russia because of religion. It is as I have said—the Jew ruins the peasants, with the result that conflicts occur when the latter have lost all their worldly possessions and have nothing to live upon. There are many good Jews in Russia, and they are respected. Jewish genius is appreciated in Russia, and the Jewish artist honored. Jews also appear in the financial world in Russia. The Russian Government affords the same protection to the Jews that it does to any other of its citizens, and when a riot occurs and Jews are attacked the officials immediately take steps to apprehend those who began the riot, and visit severe punishment upon them."[7]

A memorial to the 1903 pogroms now stands in Kishinev.[8]

Results of the pogroms

Despite a worldwide outcry, only two men were sentenced to seven and five years and twenty-two were sentenced for one or two years. This pogrom was instrumental in convincing tens of thousands of Russian Jews to leave for the West or Palestine.

As such, it became a rallying point for early Zionists, especially what would become Revisionist Zionism, inspiring early self-defense leagues under leaders like Ze'ev Jabotinsky.

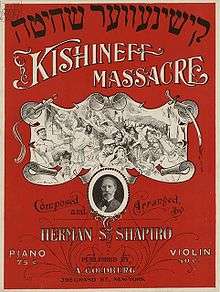

In the arts

A large number of artists and writers addressed the pogrom. Russian authors such as Vladimir Korolenko wrote about the pogrom in House 13, while Tolstoy and Gorky wrote condemnations blaming the Russian government—a change from the earlier pogroms of the 1880s, when most members of the Russian intelligentsia were silent. It also had a major impact on Jewish art and literature. Playwright Max Sparber took the Kishinev pogrom as the subject for one of his earliest plays. Poet Chaim Bialik wrote "In the City of Slaughter," about the perceived passivity of the Jews in the face of the mobs:

- ... the heirs

- Of Hasmoneans lay, with trembling knees,

- Concealed and cowering—the sons of the Maccabees!

- The seed of saints, the scions of the lions!

- Who, crammed by scores in all the sanctuaries of their shame,

- So sanctified My name!

- It was the flight of mice they fled,

- The scurrying of roaches was their flight;

- They died like dogs, and they were dead!

In Israel Zangwill's 1908 play The Melting Pot, it is in the wake of the Kishinev pogrom that the Jewish hero emigrates to America.

Joann Sfar's series of graphic novels "Klezmer" depicts life in Odessa, Ukraine at this time; in the final Volume 5 "Kishinev-des-fous", the first pogrom affects the characters.

Notes

- ↑ Davitt, Michael (1903). Within The Pale. London: Hurst and Blackett. pp. 98–100.

- ↑

Rosenthal, Herman; Rosenthal, Max (1901–1906). "Kishinef (Kishinev)". In Singer, Isidore; et al. Jewish Encyclopedia. New York: Funk & Wagnalls Company.

Rosenthal, Herman; Rosenthal, Max (1901–1906). "Kishinef (Kishinev)". In Singer, Isidore; et al. Jewish Encyclopedia. New York: Funk & Wagnalls Company. - ↑ YIVO Institute for Jewish Research: Pogroms

- ↑ "Jewish Massacre Denounced". New York Times. April 28, 1903. p. 6.

- ↑ "The voice of America on Kishineff, ed. by Cyrus Adler". Retrieved 26 March 2016.

- ↑ "Russia at the Bar of the American People". Retrieved 26 March 2016.

- ↑ "Current Literature: A Magazine of Contemporary Record (New York). Vol. XXXV., No.1. July, 1903. Current Opinion. V.35 (1903). p. 16". babel.hathitrust.org.

- ↑ "Picasa Web Albums - Ronnie - kishinev". Retrieved 26 March 2016.

References

- Kishinev Pogrom unofficial commemorative website

-

Rosenthal, Herman; Rosenthal, Max (1901–1906). "Kishinef (Kishinev)". In Singer, Isidore; et al. Jewish Encyclopedia. New York: Funk & Wagnalls Company.

Rosenthal, Herman; Rosenthal, Max (1901–1906). "Kishinef (Kishinev)". In Singer, Isidore; et al. Jewish Encyclopedia. New York: Funk & Wagnalls Company. - Penkower, Monty Noam (2004). "The Kishinev Pogrom of 1903: A Turning Point in Jewish History". Modern Judaism. 24 (3): 187–225. JSTOR 1396539.

- Resources about the pogrom