Israel Zangwill

| Israel Zangwill | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born |

21 January 1864 London, England, United Kingdom |

| Died |

1 August 1926 (aged 62) Midhurst, West Sussex, England, United Kingdom |

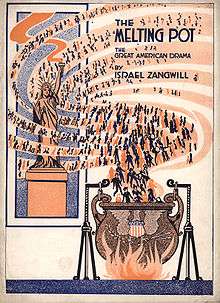

| Notable works | The Melting Pot (1908) |

| Spouse | Edith Ayrton |

Israel Zangwill (21 January 1864 – 1 August 1926) was a British author at the forefront of cultural Zionism during the 19th century, he was a close associate of Theodor Herzl. He later rejected the search for a Jewish homeland and became the prime thinker behind the territorial movement.

Early life and education

Zangwill was born in London on 21 January 1864, in a family of Jewish immigrants from the Russian Empire. His father, Moses Zangwill, was from what is now Latvia, and his mother, Ellen Hannah Marks Zangwill, was from what is now Poland. He dedicated his life to championing the cause of people he considered oppressed, becoming involved with topics such as Jewish emancipation, Jewish assimilation, territorialism, Zionism, and women's suffrage. His brother was novelist Louis Zangwill.[1]

Zangwill received his early schooling in Plymouth and Bristol. When he was nine years old, Zangwill was enrolled in the Jews' Free School in Spitalfields in east London, a school for Jewish immigrant children. The school offered a strict course of both secular and religious studies while supplying clothing, food, and health care for the scholars; presently one of its four houses is named Zangwill in his honour. At this school he excelled and even taught part-time, eventually becoming a full-fledged teacher. While teaching, he studied for his degree from the University of London, earning a BA with triple honours in 1884.

Career

Writings

He had already written a tale entitled The Premier and the Painter in collaboration with Louis Cowen, when he resigned his position as a teacher owing to differences with the school managers and ventured into journalism. He initiated and edited Ariel, The London Puck, and did miscellaneous work for the London press.[2]

Zangwill's work earned him the nickname "the Dickens of the Ghetto".[3] He wrote a very influential novel Children of the Ghetto: A Study of a Peculiar People (1892).

The use of the metaphorical phrase "melting pot" to describe American absorption of immigrants was popularised by Zangwill's play The Melting Pot,[4] a success in the United States in 1909–10.

When The Melting Pot opened in Washington D.C. on 5 October 1909, former President Theodore Roosevelt leaned over the edge of his box and shouted, "That's a great play, Mr. Zangwill, that's a great play."[5]

In 1912 Zangwill received a letter from Roosevelt in which Roosevelt wrote of the Melting Pot "That particular play I shall always count among the very strong and real influences upon my thought and my life."[6]

The protagonist of the play, David, emigrates to America after the Kishinev pogrom in which his entire family is killed. He writes a great symphony named "The Crucible" expressing his hope for a world in which all ethnicity has melted away, and becomes enamored of a beautiful Russian Christian immigrant named Vera. The dramatic climax of the play is the moment when David meets Vera's father, who turns out to be the Russian officer responsible for the annihilation of David's family. Vera's father admits guilt, the symphony is performed to accolades, David and Vera live happily ever after, or, at least, agree to wed and kiss as the curtain falls.

"Melting Pot celebrated America's capacity to absorb and grow from the contributions of its immigrants."[7] Zangwill was writing as "a Jew who no longer wanted to be a Jew. His real hope was for a world in which the entire lexicon of racial and religious difference is thrown away."[8]

Zangwill wrote many other plays, including, on Broadway, Children of the Ghetto (1899), a dramatisation of his own novel, directed by James A. Herne and starring Blanche Bates, Ada Dwyer, and Wilton Lackaye; Merely Mary Ann (1903) and Nurse Marjorie (1906), both of which were directed by Charles Cartwright and starred Eleanor Robson. Liebler & Co. produced all three plays as well as The Melting Pot. Daniel Frohman produced Zangwill's 1904 play, The Serio-Comic Governess, featuring Cecilia Loftus, Kate Pattison-Selten, and Julia Dean.[9] In 1931 Jules Furthman adapted Merely Mary Ann for a Janet Gaynor film.

Zangwill's simulation of Yiddish sentence structure in English aroused great interest. He also wrote mystery works, such as The Big Bow Mystery (1892), and social satire such as The King of Schnorrers (1894), a picaresque novel (which became a short-lived musical comedy in 1979). His Dreamers of the Ghetto (1898) includes essays on famous Jews such as Baruch Spinoza, Heinrich Heine and Ferdinand Lassalle.

The Big Bow Mystery was the first locked room mystery novel. It has been almost continuously in print since 1891 and has been used as the basis for three commercial movies.[10]

Another widely-produced play was The Lens Grinder, based on the life of Spinoza.

The following is a list of his "of the Ghetto" books:

- Children of the Ghetto: A Study of a Peculiar People (1892)

- Grandchildren of the Ghetto (1892)

- Dreamers of the Ghetto (1898)

- Ghetto Tragedies, (1899)

- Ghetto Comedies, (1907)

Other books by the author:

- Chosen Peoples, (1919)

- The Big Bow Mystery (1892)

- The King of Schnorrers (1894)

- The Master (1895) (based on the life of friend and illustrator George Wylie Hutchinson)[12]

- The Melting Pot(1909)

- The Old Maid’s Club (1892)

- The Bachelors' Club (London : Henry, 1891)

- The Serio-Comic Governess (1904)

- Without Prejudices (1896)

- Merely Mary Ann (1904)

- The Grey Wig: Stories and Novelettes (1903) which include The Grey Wig; Chasse-Croise; The Woman Beater; The Eternal Feminine; The Silent Sisters

Politics

Zangwill as caricatured by Walter Sickert in Vanity Fair, February 1897.

Zangwill endorsed feminism and pacifism,[10] but his greatest effect may have been as a writer who popularised the idea of the combination of ethnicities into a single, American nation. The hero of his widely-produced play, The Melting Pot, proclaims: "America is God's Crucible, the great Melting-Pot where all the races of Europe are melting and reforming... Germans and Frenchmen, Irishmen and Englishmen, Jews and Russians – into the Crucible with you all! God is making the American."'[13]

Jewish politics

Zangwill was also involved with specifically Jewish issues as an assimilationist, an early Zionist, and a territorialist.[10] Zangwill quit Zionism in 1905 to become a major promoter of Territorialism, advocating a Jewish homeland in whatever land might be available.[14]

Zangwill is known incorrectly for inventing the slogan "A land without a people for a people without a land" describing Zionist aspirations in the Biblical land of Israel. He did not invent the phrase; he acknowledged borrowing it from Lord Shaftesbury.[15] In 1853, during the preparation for the Crimean War, Shaftesbury wrote to Foreign Minister Aberdeen that Greater Syria was "a country without a nation" in need of "a nation without a country... Is there such a thing? To be sure there is, the ancient and rightful lords of the soil, the Jews!" In his diary that year he wrote "these vast and fertile regions will soon be without a ruler, without a known and acknowledged power to claim dominion. The territory must be assigned to some one or other... There is a country without a nation; and God now in his wisdom and mercy, directs us to a nation without a country."[16] Shaftesbury himself was echoing the sentiments of Alexander Keith, D.D.[17]

In 1901 in the periodical New Liberal Review, Zangwill wrote that "Palestine is a country without a people; the Jews are a people without a country".[15][18] Theodor Herzl fared best with Israel Zangwill, and Max Nordau. They were both well-known writers or 'men of letters' - imagination that engendered understanding. Baron Albert Rothschild had little to do with the Jews. On Herzl's visits to London, they co-operated closely.[19] In a debate at the Article Club in November 1901 Zangwill was still misreading the situation: "Palestine has but a small population of Arabs and fellahin and wandering, lawless, blackmailing Bedouin tribes."[20] Then, in the dramatic voice of the Wandering Jew, "restore the country without a people to the people without a country. (Hear, hear.) For we have something to give as well as to get. We can sweep away the blackmailer—be he Pasha or Bedouin—we can make the wilderness blossom as the rose, and build up in the heart of the world a civilisation that may be a mediator and interpreter between the East and the West."[20]

In 1902, Zangwill wrote that Palestine "remains at this moment an almost uninhabited, forsaken and ruined Turkish territory".[21] However, within a few years, Zangwill had "become fully aware of the Arab peril", telling an audience in New York, "Palestine proper has already its inhabitants. The pashalik of Jerusalem is already twice as thickly populated as the United States" leaving Zionists the choice of driving the Arabs out or dealing with a "large alien population".[22] He moved his support to the Uganda scheme, leading to a break with the mainstream Zionist movement by 1905.[23] In 1908, Zangwill told a London court that he had been naive when he made his 1901 speech and had since "realized what is the density of the Arab population", namely twice that of the United States.[24] In 1913 he criticised those who insisted on repeating that Palestine was "empty and derelict" and who called him a traitor for reporting otherwise.[25]

According to Ze'ev Jabotinsky, Zangwill told him in 1916 that, "If you wish to give a country to a people without a country, it is utter foolishness to allow it to be the country of two peoples. This can only cause trouble. The Jews will suffer and so will their neighbours. One of the two: a different place must be found either for the Jews or for their neighbours".[26]

In 1917 he wrote "'Give the country without a people,' magnanimously pleaded Lord Shaftesbury, 'to the people without a country.' Alas, it was a misleading mistake. The country holds 600,000 Arabs."[27]

In 1921 Zangwill wrote "If Lord Shaftesbury was literally inexact in describing Palestine as a country without a people, he was essentially correct, for there is no Arab people living in intimate fusion with the country, utilizing its resources and stamping it with a characteristic impress: there is at best an Arab encampment, the break-up of which would throw upon the Jews the actual manual labor of regeneration and prevent them from exploiting the fellahin, whose numbers and lower wages are moreover a considerable obstacle to the proposed immigration from Poland and other suffering centers".[28]

After having for a time endorsed Theodor Herzl, including presiding over a meeting at the Maccabean Club, London, addressed by Herzl on 24 November 1895, and endorsing the main Palestine-oriented Zionist movement, Zangwill quit the established philosophy and founded his own organisation, named the Jewish Territorialist Organization in 1905. Its goal was to create a Jewish homeland in whatever possible territory in the world could be found for them, with speculations including Canada, Australia, Mesopotamia, Uganda and Cyrenaica. [29]

Zangwill died in 1926 in Midhurst, West Sussex.

Personal life

Zangwill married Edith Ayrton, a feminist and author who was the daughter of cousins William Edward Ayrton and Matilda Chaplin Ayrton.[30] Their youngest of two sons was the prominent British psychologist, Oliver Zangwill.

Popular culture

- Zangwill features as a recurring character in the novels of Will Thomas.

Bibliography

References

- ↑ Louis Zangwill in Jewish Encyclopedia

- ↑

One or more of the preceding sentences incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Zangwill, Israel". Encyclopædia Britannica. 28 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 956.

One or more of the preceding sentences incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Zangwill, Israel". Encyclopædia Britannica. 28 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 956. - ↑ Israel Zangwill – A Sketch, by Emanuel Elzas; in the San Francisco Call; published 25 August 1895; retrieved 14 May 2013; archived at the Library of Congress

- ↑ Werner Sollers, Beyond Ethnicity: Consent and Descent in American Culture (1986), Chapter 3 "Melting Pots"

- ↑ Guy Szuberla, "Zangwill's The Melting Pot Plays Chicago," MELUS, Vol. 20, No. 3, History and Memory. (Autumn, 1995), pp. 3–20.

- ↑ This passage is quoted on page 131 of "Theodore Roosevelt and the Idea of Race" by Thomas G.Dyer 1980 Louisiana State University Press (Paperback edition 1992). A footnote shows the letter to have been written on 27 November 1912. This letter is held in the Roosevelt Collection, Library of Congress.

- ↑ Kraus, Joe, "How The Melting Pot Stirred America: The Reception of Zangwill's Play and Theater's Role in the American Assimilation Experience," MELUS, Vol. 24, No. 3, Varieties of Ethnic Criticism. (Autumn, 1999), pp. 3–19.

- ↑ Jonathan Sacks The Home We build Together, Continium Books, 2007, P. 26

- ↑ Burns Mantle and Garrison P. Sherwood, eds., The Best Plays of 1899–1909, pp. 351, 449, 465–466, 521–522.

- 1 2 3 Rochelson, Meri-Jane (1 January 1992). "Review of Dreamer of the Ghetto: The Life and Works of". AJS Review. 17 (1): 120–123. JSTOR 1487027.

- ↑ A Jew in the Public Arena: The Career of Israel Zangwill By Meri-Jane Rochelson, p.30

- ↑ Sandra Barry, "What's in a Name? The Gilbert Stuart Newton Plaque Error", Acadiensis, XXV, 1 (Autumn, 1995), p. 107.

- ↑ As quoted in Gary Gerstle American Crucible; Race and Nation in the Twentieth Century, Princeton University Press, 2001, p. 51

- ↑ Israel Zangwill, Joseph Leftwich, Yoseloff, 1957, p. 219

- 1 2 Garfinkle, Adam M., "On the Origin, Meaning, Use and Abuse of a Phrase." Middle Eastern Studies, London, October 1991, vol. 27

- ↑ Shaftsbury as cited in Hyamson, Albert, "British Projects for the Restoration of Jews to Palestine," American Jewish Historical Society, Publications 26, 1918 p. 140; and in Garfinkle, Adam M., "On the Origin, Meaning, Use and Abuse of a Phrase." Middle Eastern Studies, London, October 1991, vol. 27. See also Mideast Web: British Support for Jewish Restoration

- ↑ A Land without a People for a People without a Land;" An oft-cited Zionist slogan was neither Zionist nor popular,"Diana Muir, Middle Eastern Quarterly, Spring 2008, Vol. 15, No. 2, pp. 55-62.

- ↑ Israel Zangwill, "The Return to Palestine", New Liberal Review, Dec. 1901, p. 615

- ↑ Vital, 442

- 1 2 Israel Zangwill, The Commercial Future of Palestine, Debate at the Article Club, 20 November 1901. Published by Greenberg & Co. Also published in English Illustrated Magazine, Vol. 221 (Feb 1902) pp. 421–430.

- ↑ Israel Zangwill (22 February 1902). "Providence, Palestine and the Rothschilds". The Speaker. 4 (125): 582–583.

- ↑ I. Zangwill, The Voice of Jerusalem, MacMillan, 1921, p. 92, reporting 1904 speech.

- ↑ H. Faris, Israel Zangwill's challenge to Zionism, Journal of Palestine Studies, Vol. 4, No. 3 (Spring, 1975), pp. 74–90

- ↑ Maurice Simon (1937). Speeches Articles and Letters of Israel Zangwill. London: The Soncino Press. p. 268.

- ↑ Simon (1937), pp. 313–314. He continued, "Well, consistency may be a political virtue, but I see no virtue in consistent lying."

- ↑ Cited in Yosef Gorny, Zionism and the Arabs, 1882–1948 (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1987), p. 271

- ↑ I. Zangwill, The Voice of Jerusalem, MacMillan, 1921, p. 96

- ↑ Zangwill, Israel, The Voice of Jerusalem, Macmillan, New York, 1921, p. 109

- ↑ "At the centennial of his birth, even some of those who recognized the continuing relevance of his efforts to define the Jew in the modern world separated the compelling nature of his struggle from the Victorianness of his writing and the insufficiency of his solutions: territorialism, universal religion, assimilation into an American 'melting pot.' As John Gross wrote in Commentary Magazine "one honours the writer, and puts aside his books." Rochelson, Meri-Jane (1 January 1992). "Review of Dreamer of the Ghetto: The Life and Works of". AJS Review. 17 (1): 120–123. JSTOR 1487027.

- ↑ Nyenhuis, Jacob E. (2003). "notes". Myth and the creative process: Michael Ayrton and the myth of Daedalus, the maze maker. Detroit: Wayne State University Press. p. 207. ISBN 0-8143-3002-9.

Own writing

- Israel Zangwill, "The Return to Palestine", New Liberal Review, Dec. 1901

- Zangwill, Israel (2004) [1902]. Children of the Ghetto. Black Apollo Press. ISBN 1-900355-30-2.

- Israel Zangwill, (22 February 1902), "Providence, Palestine and the Rothschilds", The Speaker 4 (125)

- Israel Zangwill, The Voice of Jerusalem, Macmillan, New York, 1921

Bibliography

- Adams, Elsie Bonita (1971). Israel Zangwill. New York: Twayne.

- Gross, John (December 1964). "Zangwill in Retrospect". Commentary. 38.

- Guigui, Jacques Ben (1975). Israel Zangwill: Penseur el Ecrivain 1864–1926. Toulouse: lmprimerie Toulousaine-R.Lion.

- Mantle, Burns; Sherwood, Garrison P., eds. (1944). The Best Plays of 1899–1909. Philadelphia: The Blakiston Company.

- Nahshon, Edna. From the Ghetto to the Melting Pot: Israel Zangwill's Jewish Plays. Wayne State University Press.

- Rochelson, Meri-Jane (2008). A Jew in the Public Arena: The Career of Israel Zangwill. Detroit: Wayne State University Press.

- Udelson, Joseph H. (1990). Dreamer of the Ghetto: The Life and Works of Israel Zangwill. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press.

- Vital, David (October 1984). "Zangwill and Modern Jewish Nationalism". Modern Judaism. 4 (3): 243–253. JSTOR 1396299.

- Vital, David (1999). A People Apart: The Jews in Europe 1789–1939. Oxford: Oxford Modern History.

- Wohlgelernter, Maurice (1964). Israel Zangwill: A Study. New York: Columbia University Press.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Israel Zangwill. |

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Israel Zangwill |

- Literature by and about Israel Zangwill in University Library JCS Frankfurt am Main: Digital Collections Judaica

- Works by Israel Zangwill at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about Israel Zangwill at Internet Archive

- Works by Israel Zangwill at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

- The personal papers of Israel Zangwill are kept at the Central Zionist Archives in Jerusalem. The notation of the record group is A120.

- Israel Zangwill, The Principle of Nationalities (1917)

- Israel Zangwill and Children of the Ghetto

- The Zionist Exposition

- Jewish Virtual Library

- Internet Broadway Database

- Jewish Museum in London

| Awards and achievements | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by Jack Dempsey |

Cover of Time Magazine 17 September 1923 |

Succeeded by John Pierpont Morgan, Jr. |