Kourion

| Κούριον | |

Kourion Theatre | |

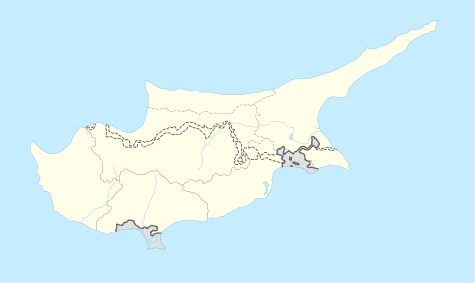

Shown within Cyprus | |

| Alternate name | Curium |

|---|---|

| Location | Episkopi, Limassol District, Cyprus |

| Coordinates | 34°39′51″N 32°53′16″E / 34.6642°N 32.8877°ECoordinates: 34°39′51″N 32°53′16″E / 34.6642°N 32.8877°E |

| Type | Settlement |

| Management | Cyprus Department of Antiquities |

Kourion (Greek: Κούριον) or Latin: Curium, was an ancient city on the southwestern coast of Cyprus, the surrounding Kouris River Valley being occupied from at least the Ceramic Neolithic period (4500-3800 BCE) to the present. The acropolis of Kourion, located 1.3 km southwest of Episkopi and 13 km west of Limassol, is located atop a limestone promontory nearly one hundred meters in height along the coast of Episkopi Bay. The Kourion archaeological area lies within the Akrotiri West Sovereign Base Area, which forms part of the British Overseas Territory of Akrotiri and Dhekelia. The Kourion Archaeological Area, and all antiquities within the Akrotiri West Sovereign Base are managed by the Cyprus Department of Antiquity. Kourion is a listed UNESCO World Heritage Site.

Kourion was an urban center of considerable importance within Cyprus, reaching the climax of its influence in the Roman and Late Roman periods. The city is mentioned by several ancient authors including: Ptolemy (v. 14. § 2), Stephanus of Byzantium, Hierocles, and Pliny the Elder. Though Kourion attained its highest prominence under the Romans, the Kouris River Valley has seen occupation from the Ceramic Neolithic period to the present village of Episkopi. Occupation on the acropolis appears to have been from the Late Classical period at latest until the Arab raids of the 7th century CE.

History of Kourion

The earliest occupation within the Kouris Valley is the hilltop settlement of Sotira-Teppes, located 9 km northwest of Kourion.[1][2] This settlement dates to the Ceramic Neolithic period (circa 5500-4000 BCE). Another Ceramic Neolithic hilltop settlement has been excavated at Kandou-Koupovounos, another hilltop situated along the east bank of the Kouris River. In the Chalcolithic period (3800-2300 BCE) settlement shifted to the site of Erimi-Pamboules, located within the limits of the village of Erimi. Erimi-Pamboules was occupied from the conclusion of the Ceramic Neolithic through the Chalcolithic period (3400-2800 BCE).

Occupation of the Early Cypriot period ( circa 2300-1900 BCE) is uninterrupted from the preceding Chalcolithic period, with occupation continuing along the Kouris River Valley and the drainages to the west. Sotira-Kaminoudhia, located to the northwest of Sotira-Teppes, on the lower slope of the hill, was settled. It dates from the Late Chalcolithic to EC (Early Cypriot) I (ca.2400-2175 BCE). In the ECIII-LC (Late Cypriot) IA (ca.2400-1550 BCE) a settlement was established 0.8 km east of Episkopi at Episkopi-Phaneromeni. The Middle Cypriot (1900-1600 BCE) is a transitional period in the Kouris River Valley. The settlements established during the MC flourished into urban centers in the Late Cypriot II-III, especially Episkopi-Bamboula.[3]

In the Late Cypriot I-III (1600-1050 BCE) the settlements of the Middle Cypriot period developed into complex urban center within the Kouris Valley, which provided a corridor in the trade of Troodos copper, controlled through Alassa and Episkopi-Bamboula. In the MCIII-LC IA a settlement was occupied at Episkopi-Phaneromeni. Episkopi-Bamboula, located on a low hill 0.4 km west of the Kouris and east of Episkopi, was an influential urban center from the LC IA-LCIII.[4][5] The town flourished in the 13th century BCE before being abandoned c.1050 BCE.[6][7] In the Cypro-Geometric (1050-750 BCE)the Kingdom of Kourion was established, though the occupational center remains unidentified.

In the Cypro-Archaic period (750-475 BCE) the Kingdom of Kourion was among the most influential kingdoms of Cyprus. In 672 Damasos, king of Kourion, is recorded as a tributary of Esarhaddon of Assyria as Damasu of Kuri. Between 569 and ca.546 BCE Cyprus was under Egyptian administration. In 546 BCE Cyrus I of Persia extended Persian authority over the Kingdoms of Cyprus, including the Kingdom of Kourion. During the Ionian Revolt (499-493 BCE), Stasanor, king of Kourion, aligned himself with Onesilos, king of Salamis, the leader of a Cypriot alliance against the Persians. In 497 Stasanor betrayed Onesilos in battle against the Persian general Artybius, resulting in a Persian victory over the Cypriot poleis and the consolidation of Persian control of Cyprus.

In the Classical Period (475-333 BCE) the earliest occupation of the acropolis was established, though the primary site of settlement is unknown. King Pasikrates of Kourion is recorded as having aided Alexander the Great in the siege of Tyre in 332 BCE. Pasikrates ruled as a vassal of Alexander but was deposed in the struggles for succession amongst the diadochi. In 294 BCE the Ptolemies consolidated control of Cyprus, and Kourion came under Ptolemaic governance.[8]

In 58 BCE the Council of the Plebs (Consilium Plebis) passed the Lex Clodia de Cyprus, annexing Cyprus to the province of Cilicia and bringing it under Roman rule. Between 47 and 31 BCE, Cyprus was returned to Ptolemaic rule under Marc Antony and Cleopatra VII, reverting to Roman rule after the defeat of Antony. In 22 BCE, Cyprus was separated from the province of Cilicia, being established as a Senatorial province under a proconsul. In the Roman period, Kourion was among the most prominent cities of the Cyprus, the Sanctuary of Apollo Hylates being a Pan-Cypriot sanctuary alongside the Temple of Zeus Salaminos at Salamis and Aphrodite at Kata Paphos.

In the mid-1st century Christianity was introduced to Kourion, presumably by Saints Paul and Barnabas during Paul's first missionary journey. During the persecutions of Diocletian, Philoneides, the Bishop of Kourion, was martyred. In 341 CE,the Bishop Zeno was instrumental in the Council of Ephesus in asserting the independence of the Cypriot church.

In the later-4th century (c.365/70) Kourion have been hit by five strong earthquakes within a period of eighty years, as can be seen by the archaeological remains throughout the site, and suffered a total destruction.[9] In the early-5th century Kourion was reconstructed, the reconstruction including the construction of the ecclesiastical complex on the western side of the acropolis. In 649 the Arab raids resulted in the destruction of the acropolis, after which the center of occupation was relocated to Episkopi, 2.0 km northeast of the acropolis. Episkopi was named for the seat of the Bishop (Episcopus).[8][10][11]

History of excavations

The site of Kourion was identified in the 1820s by Carlo Vidua. In 1839 and 1849, respectively, Lorenzo Pease and Ludwig Ross identified the Sanctuary of Apollo Hylates to the west of the acropolis. In 1874-5, Luigi Palma di Cesnola, then American and Russian consul to the Ottoman government of Cyprus, extensively looted the cemetery of Ayios Ermoyenis and the Sanctuary of Apollo Hylates.[12][13] Between 1882 and 1887 several unauthorized private excavations were conducted prior to their illegalization by British High Commissioner, Sir Henry Bulwer in 1887.

In 1895 the British Museum conducted the first quasi-systematic excavations at Kourion as part of the Turner Bequest Excavations.[14][15] P. Dikaios of the Department of Antiquities conducted excavations in the Kaloriziki Cemetery in 1933.

Between 1934 and 1954, G. McFadden, B.H. Hill and J. Daniel conducted systematic excavations at Kourion for the University Museum at the University of Pennsylvania. Following the death of G. McFadden in 1953, the project and its publication stalled. The excavations of the Early Christian Basilica on the acropolis were continued by A.H.S. Megaw from 1974-9.[16][17][18]

The Cyprus Department of Antiquities has conducted numerous excavations at Kourion including: M. Loulloupis (1964–74), A. Chritodoulou (1971-4), and D. Christou (1975-1998).[19] Between 1978 and 1984 D. Soren conducted excavations at the Sanctuary of Apollo Hylates, and on the acropolis between 1984 and 1987. D. Parks directed excavations within the Amathus Gate Cemetery between 1995 and 2000.[20][21] The 'Amathus Gate' cemetery was excavated by D. Parks between 1995 and 2000.[22]

Since 2012 the Kourion Urban Space Project, under the direction of T.W. Davis of the Charles D. Tandy Institute of Archaeology, has excavated on the acropolis.[23]

The Archaeological Remains

The majority of the archaeological remains within the Kourion Archaeological Area date to the Roman and Early Byzantine periods. The acropolis and all archaeological remains within the area are managed and administered by the Cyprus Department of Antiquities. Though the area of the acropolis and its surroundings contain innumerable remains from Antiquity, only the most important are cited hereafter.

The Theatre

The theatre of Kourion was excavated by the University Museum Expedition of the University of Pennsylvania between 1935 and 1950. The theatre was constructed into the northern slope of the defile descending to the Amathus Gate, thus utilizing the slope of the hill to partially support the weight of the seating in the cavea. This architectural arrangement in typical throughout theatres of the Eastern Mediterranean. The theatre was initially constructed on a smaller scale in the late-second century BCE. The theatre was repaired in the late-first centiry BCE, likely following the earthquake of 15 BCE. The theatre's stage was seemingly reconstructed in 64/65 CE by Quintus Iulius Cordus, the proconsul. The theatre received an extensive renovation and enlargement under Trajan in 111 CE, bringing the theatre to its presently preserved extent. Between 214 and 217 CE, the theatre was modified to accommodate gladiatorial games and venationes but it was restored to its original form as a theatre after 250 CE. The theatre was abandoned in the later-fourth century CE, likely the result of successive seismic events, the earthquake of 365/70 perhaps resulting in its abandonment.[16] The enlarged cavea of the Roman phases could have accommodated an audience of as many as 3,500. The stage building (scaenae frons) is preserved only in its foundations, though this would have originally obscured the view of the Mediterranean to the south. The present remains of the theatre have been restored extensively. [24][25] The theatre is one of the venues for the International Festival of Ancient Greek Drama.[26]

The Baths and House of Eustolios

Situated along the crest of the southeastern cliffs immediately east and slightly above the theatre is the House and Baths of Eustolios. The structure was excavated by the Pennsylvania University Museum in 1933 and 1948. The presently visible residence was constructed in the late-fourth or early-fifth centuries CE and remained occupied until the mid-seventh century CE. The household and bath annex on the northern side contains more than thirty rooms. The complex was entered from the west, the visitor passing into a rectangular forecourt. A salutatory inscription in the vestibule beyond the forecourt reads, "Enter for the good luck of the house." Rooms were arranged north and south of this forecourt and the vestibule, including a peristyle courtyard to the south at its eastern extent. The southern peristyle was arranged around a central pool and is the centerpiece of the household, its porticoes adorned with elaborate mosaics. An inscription within the peristyle identifies the builder as Eustolios, who had built the structure to alleviate the suffering of the citizens of Kourion, presumably in response to the earthquakes of the late-fourth century. The inscription identifies the present patron of the house as Christ. To the north were servant's and storage areas and the bath annex. The baths are elaborately decorated with marble revetment and mosaic floors. The most prominent mosaic pavement depicts a personification of Ktisis (Creation) holding an architect's ruler. [27][28] The household was probably constructed as an private elite-residence, but was converted into a publicly-accessible bathing facility in the early-fifth century.

House of Achilles

The House of Achilles, located at the northwestern extent of the acropolis, at the southern end of a saddle connecting the acropoline promontory to the hills to the north and west. It was located outside the walls, which has been partially exposed immediately to the south, and near the proposed site of the Paphos Gate.

The House of Achilles was constructed in the early-fourth century CE. The structure is arrayed around a central peristyle courtyard with fragmentarily preserved mosaic pavements in the northeastern portico. The most important mosaic depicts the unveiling of Achilles’ identity by Odysseus in the court of Lycomedes of Skyros when his mother, Thetis, had hidden him there amongst the women so that he might not be sent to war against the Trojans. In another room, a mosaic depicting Thetis bathing Achilles for the first time has been fragmentarily preserved. In yet another room a fragmentary mosaic depicts the Rape of Ganymede. Though it has been tentatively identified as a private-house, it may have functioned as a public reception hall.

House of the Gladiators

The so-called House of the Gladiators is located south and east of the House of Achilles. The structure dates to the late-third century CE. The structure has been interpreted as an elite-private residence, or perhaps more probably as a public palaestra. The later identification is supported by the absence of many rooms appropriate for living spaces and that the structure was entered from the east through the attached bath complex. The main wing of the structure is arranged around a central peristyle courtyard, the northern and eastern porticos of which possess preserved mosaic pavements depicting gladiatorial combats. The eastern portico of the atrium contains two panels depicting gladiators in combat, the only such mosaics in Cyprus.[24][25]

Forum and the Baths

The agora was constructed in the 3rd century CE over the remains of a public building of the 4th to the early-1st centuries BCE. The open agora was flanked on opposite sides by porticoes with a monumental nymphaeum along its northern side and a bath complex (thermae) constructed around the nymphaeum. The nymphaeum, measuring 45x15m was constructed in 1st century CE and renovated during the reign of Trajan (98-117) at which time the baths were constructed around it, along the northern side of the agora.[29] The baths are divided into undressing rooms (apodyterium), warm rooms (tepidarium), a hot room (caldarium), and a cold room (frigidarium) according to the Roman customs of bathing.

Episcopal Precinct of Kourion

The Episcopal Precinct of Kourion, constructed in the early 5th century CE and successively renovated in the 6th century, is among the most important Early Christian monuments yet excavated in Cyprus. The three-aisled basilica that forms the core of the precinct functioned as the seat (cathedra) of the Bishop of Kourion. A second attached chapel was intended for the receipt of the offerings of the congregation (diakonikon). Within the precinct are the baptistery and the bishop’s palace. The precinct was destroyed during the Arab Raiding of the 7th century after which the settlement was reestablished in Episkopi.

The Northwest Basilica

Located northwest of the acropolis, a three-apse basilica was constructed in the late-5th century. The basilica had three-aisles and was accessed through a peristyle courtyard and narthex west of the basilica. A chapel was constructed within the church complex north of the main basilica. The basilica was destroyed by the Arab raids in the mid-7th century.

The Coastal Basilica

Located below the west cliffs of the acropolis, a three-apse and three-aisled basilica was constructed in the early-6th century. The church had an atrium to the west with porticoes on all sides of the atrium and a baptistery to the north.

The Sanctuary of Apollo Hylates

The Sanctuary of Apollo Hylates, located 1.7 km west of the acropolis, was a Pan-Cypriot sanctuary, third in importance only to the Sanctuaries of Zeus Salaminos and Paphian Aphrodite. The earliest archaeological evidence indicates that the sanctuary was established in the late-8th century BCE, the sanctuary being dedicated to "the God," apparently unassociated with Apollo. By the mid-3rd century BCE, the sanctuary was dedicated to Apollo Hylates. The sanctuary at present was constructed in the 1st century and early 2nd century. The temple was abandoned in the late-4th century.

The Stadium

Located 0.5 km west of the acropolis, the stadium of Kourion was constructed during the Antonine period (138-180). The seating formed a u-shape around the south, west and north sides of the stadium, measuring 217m long and 17m wide. The stadium was 187m long, with a starting line marked put two stone circular posts, set wide enough to accommodate eight runners.

Paragliding

Kourion is a major paragliding site in Cyprus and is flyable on most days of the year. Many pilots from all over Cyprus and visitors to the island use the area as a launching spot.

References

- ↑ "Ancient Cyprus in the British Museum: Early Prehistory, about 9000-2500 BC". British Museum. Retrieved 26 February 2015.

- ↑ "Digital Kourion- Sotira Teppes". Penn Museum. Retrieved 26 February 2015.

- ↑ "Ancient Cyprus in British Museum: Early and Middle Bronze Ages, c.2500-1650 BCE". British Museum. Retrieved 26 February 2015.

- ↑ Herodotus. The Histories 5.113. Translation by A. D. Godley (1920). Harvard University Press. Online edition by the Perseus Project.

- ↑ Jones, H.L., ed. (1924). The Geography of Strabo - Book 14,6.3. William Heinemann / Harvard University Press. Online edition by the Perseus Project.

- ↑ "Bamboula". Penn Museum. Retrieved 15 February 2015.

- ↑ "Ancient Cyprus in the British Museum: Late Bronze Age (c.1650-1050 BCE)". British Museum. Retrieved 26 February 2015.

- 1 2 Christou, Demos (2008). Kourion: Its Monuments and Local Museum. Nicosia: Filokipros. pp. 17–8.

- ↑ Soren, D. (1988). "The Day the World Ended at Kourion. Reconstructing an Ancient Earthquake". National Geographic. 174 (1): 30–53.

- ↑ Michel Lequien, Oriens christianus in quatuor Patriarchatus digestus, Paris 1740, Vol. II, coll. 1057-1058

- ↑ Pius Bonifacius Gams, Series episcoporum Ecclesiae Catholicae, Leipzig 1931, p. 438

- ↑ Cesnola, Luigi Palma di (1877). Cyprus: its ancient cities, tombs, and Temples. London: John Murray. pp. 295–392. Retrieved 31 January 2015.

- ↑ "Permanent Collection - Highlights". The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Retrieved 2007-03-26.

- ↑ "The British Museum Turner Bequest excavations of 1896". British Museum. Retrieved 31 January 2015.

- ↑ "Tombs from the Turner Bequest excavations". British Museum. Retrieved 31 January 2015.

- 1 2 Stillwell, Richard (1961). "Kourion: The Theater". Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society. 105 (1): 37–8. JSTOR 985354.

- ↑ "Modern excavations in the Kourion area". British Museum. Retrieved 1 February 2015.

- ↑ "Digital Kourion". Penn Museum. Retrieved 1 February 2015.

- ↑ "History of excavations in the Kourion area, continued". British Museum. Retrieved 1 February 2015.

- ↑ Soren, David (1987). Excavations at Kourion. The Sanctuary of Apollo Hylates at Kourion, Cyprus. University of Arizona Press. p. 340.

- ↑ Soren, David (1988). Kourion: the search for a lost Roman city. Doubleday. p. 233.

- ↑ "Kourion's Amathous Gate Cemetery, Cyprus. The Excavations of Danielle A. Parks". University of Glasgow. Retrieved 1 February 2015.

- ↑ "Kourion Urban Space Project, 2012". Ministry of Interior, Press and Information Office. Retrieved 1 February 2015.

- 1 2 "Kourion". Republic of Cyprus - Department of Antiquities. Retrieved 2 February 2015.

- 1 2 Nicolaou, Kyriakos (1976). "Kourion, Cyprus". In Stillwell, Richard; MacDonald, William L.; McAlister, Marian Holland. Princeton Encyclopedia of Classical Sites. ISBN 978-0691035420. Retrieved 1 October 2016.

- ↑ Cyprus Centre of International Theatre Institute site Archived August 5, 2008, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Iacovou (1987). A Guide to Kourion. Nicosia: Bank of Cyprus Cultural Foundation. pp. 30–32.

- ↑ Christou, Demos (1986). Kourion: A Complete Guide to Its Monuments and Local Museum. Nicosia: Filokipros. pp. 18–23.

- ↑ "Kourion, Cyprus". Roman aqueducts. Retrieved 2 February 2015.

![]() This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Smith, William, ed. (1854). "Curium". Dictionary of Greek and Roman Geography. 1. London: John Murray. p. 730.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Smith, William, ed. (1854). "Curium". Dictionary of Greek and Roman Geography. 1. London: John Murray. p. 730.

External links

-

Media related to Kourion at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Kourion at Wikimedia Commons - Kourion by Department of Antiquities of Cyprus

- Kourion by Limassol Municipality

- Panoramic views of Kourion

- The Cesnola Collection from Ancient Cyprus

- The Curium Soaring Club of Cyprus

- Paragliding Cyprus