Utagawa Kuniyoshi

Utagawa Kuniyoshi (歌川 国芳, January 1, 1798[1] – April 14, 1861) was one of the last great masters of the Japanese ukiyo-e style of woodblock prints and painting.[2] He was a member of the Utagawa school.[3]

The range of Kuniyoshi's subjects included many genres: landscapes, beautiful women, Kabuki actors, cats, and mythical animals. He is known for depictions of the battles of legendary samurai heroes.[4] His artwork incorporated aspects of Western representation in landscape painting and caricature.[2]

Life

He was born on January 1, 1798, the son of a silk-dyer, Yanagiya Kichiyemon,[5] originally named Yoshisaburō. Apparently he assisted his father's business as a pattern designer, and some have suggested that this experience influenced his rich use of color and textile patterns in prints. It is said that Kuniyoshi was impressed, at an early age of seven or eight, by ukiyo-e warrior prints, and by pictures of artisans and commoners (as depicted in craftsmen manuals), and it is possible these influenced his own later prints.

Yoshisaburō proved his drawing talents at age 12, quickly attracting the attention of the famous ukiyo-e print master Utagawa Toyokuni.[3] He was officially admitted to Toyokuni's studio in 1811, and became one of his chief pupils. He remained an apprentice until 1814, at which time he was given the name "Kuniyoshi" and set out as an independent artist. During this year he produced his first published work, the illustrations for the kusazōshi gōkan Gobuji Chūshingura, a parody of the original Chūshingura story. Between 1815-1817 he created a number of book illustrations for yomihon, kokkeibon, gōkan and hanashibon, and printed his stand-alone full color prints of "kabuki" actors and warriors.

Despite his promising debut, the young Kuniyoshi failed to produce many works between 1818 and 1827, probably due to a lack of commissions from publishers, and the competition of other artists within the Utagawa school (Utagawa-ryū).[3] However, during this time he did produce pictures of beautiful women ('bijinga') and experimented with large textile patterns and light-and-shadow effects found in Western art, although his attempts showed more imitation than real understanding of these principles.

His economic situation turned desperate at one point when he was forced to sell used tatami mats. A chance encounter with his prosperous fellow pupil Kunisada, to whom he felt (with some justice) that he was superior in artistic talent, led him to redouble his efforts (but did not create any lingering ill-feeling between the two, who later collaborated on a number of series).

During the 1820s, Kuniyoshi produced a number of heroic triptychs that show the first signs of an individual style. In 1827 he received his first major commission for the series, One hundred and eight heroes of the popular Suikoden all told (Tūszoku Suikoden gōketsu hyakuhachinin no hitori), based on the incredibly popular Chinese tale, the Shuihu Zhuan. In this series Kuniyoshi illustrated individual heroes on single-sheets, drawing tattoos on his heroes, a novelty which soon influenced Edo fashion. The Suikoden series became extremely popular in Edo, and the demand for Kuniyoshi’s warrior prints increased, gaining him entrance into the major ukiyō-e and literary circles.

He continued to produce warrior prints, drawing much of his subjects from war tales such as Tale of the Heike (Heike monogatari) and The rise and fall of the Minamoto and the Taira (Genpei Seisuiki). His warrior prints were unique in that they depicted legendary popular figures with an added stress on dreams, ghostly apparitions, omens, and superhuman feats. This subject matter is instilled in his works The ghost of Taira Tomomori at Daimotsu bay (Taira Tomomori borei no zu) and the 1839 triptych The Gōjō bridge (Gōjō no bashi no zu), where he manages to invoke an effective sense of action intensity in his depiction of the combat between Yoshitsune and Benkei. These new thematic styles satisfied the public’s interest in the ghastly, exciting, and bizarre that was growing during the time.

The ‘Tenpō reforms’ of 1841-1843 aimed to alleviate economic crisis by controlling public displays of luxury and wealth, and the illustration of courtesans and actors in ukiyō-e was officially banned at that time. This may have had some influence on Kuniyoshi’s production of caricature prints or comic pictures (giga), which were used to disguise actual actors and courtesans. Many of these symbolically and humorously criticized the shogunate (such as the 1843 design showing Minamoto no Yorimitsu asleep, haunted by the Earth Spider and his demons) and became popular among the politically dissatisfied public. Timothy Clark, curator of Japanese art at the British Museum, asserts that the repressive conventions of the day produced unintended consequences. The government-created limitations became a kind of artistic challenge which actually encouraged Kuniyoshi’s creative resourcefulness by forcing him to find ways to veil criticism of the shogunate allegorically.[6]

During the decade leading up to the reforms, Kuniyoshi also produced landscape prints (fūkeiga), which were outside the bounds of censorship and catered to the rising popularity of personal travel in late Edo Japan. Notable among these were Famous products of the provinces (Sankai meisan zukushi, c. 1828-30)—where he incorporated Western shading and perspective and pigments—and Famous views of the Eastern capital in the early 1830s, which was certainly influenced by Hokusai’s 1831 Thirty-six views of Mt. Fuji (Fujaku sanjurokkei). Kuniyoshi also produced during this time works of purely natural subject matter, notably of animals, birds and fish that mimicked traditional Japanese and Chinese painting.

In the late 1840s, Kuniyoshi began again to illustrate actor prints, this time evading censorship (or simply evoking creativity) through childish, cartoon-like portraits of famous kabuki actors, the most notable being "Scribbling on the storehouse wall" (Nitakaragurakabe no mudagaki). Here he creatively used elementary, childlike script sloppily written in kana under the actor faces. Reflecting his love for felines, Kuniyoshi also began to use cats in the place of humans in kabuki and satirical prints. He is also known during this time to have experimented with ‘wide-screen’ composition, magnifying visual elements in the image for a dramatic, exaggerated effect (ex. Masakado’s daughter the princess Takiyasha, at the old Soma palace). In 1856 Kuniyoshi suffered from palsy, which caused him much difficulty in moving his limbs. It is said that his works from this point onward were noticeably weaker in the use of line and overall vitality. Before his death in 1861, Kuniyoshi was able to witness the opening of the port city of Yokohama to foreigners, and in 1860 produced two works depicting Westerners in the city (Yokohama-e, ex. View of Honcho and The pleasure quarters, Yokohama). He died at the age of 65 in April 1861 in his home in Genyadana.

Pupils

Kuniyoshi was an excellent teacher and had numerous pupils who continued his branch of the Utagawa school. Among the most notable were Yoshitoshi, Yoshitora, Yoshiiku, Yoshikazu, and Yoshifuji. Typically his students began an apprenticeship in which they worked primarily on musha-e in a style similar to that of their master. As they became established as independent artists, many went on to develop highly innovative styles of their own. His most important student was Yoshitoshi, who is now regarded as the "last master" of the Japanese woodblock print.

Among those influenced by Kuniyoshi was Toyohara Chikanobu.[7] Takashi Murakami credits the pioneering influence of Kuniyoshi affecting his work.[4]

Print series

Here is a partial list of his print series, with dates:

- Illustrated Abridged Biography of the Founder (c. 1831)

- Famous Views of the Eastern Capital (c. 1834)

- Heroes of Our Country's Suikoden (c. 1836)

- Stories of Wise and Virtuous Women (c. 1841-1842)

- Fifty-Three Parallels for the Tōkaidō (1843–1845) (with Hiroshige and Toyokuni III)

- Twenty-Four Paragons of Filial Piety (1843–1846)

- Mirror of the Twenty-Four Paragons of Filial Piety (1844–1846)

- Six Crystal Rivers (1847–1848)

- Fidelity in Revenge (c. 1848)

- Twenty-Four Chinese Paragons of Filial Piety (c. 1848)

- Sixty-Nine Stations along the Kisokaido (1852)

- Portraits of Samurai of True Loyalty (1852)

- 24 Generals of Kai Province (1853)

- Half-length portrait of Goshaku Somegoro

- Takiyasha the Witch and the Skeleton Spectre

See The Kuniyoshi Project for a more extensive list.

Gallery

Multi-sheet impressions, triptychs

-

Kajiwara Kagesue, Sasaki Takatsuna, and Hatakeyama Shigetada racing to cross the Uji River before the second battle of Uji during the Genpei War[1]

- ^ Kitagawa, Hiroshi et al. (1975). The Tale of the Heike, pp. 511-513.

Yoko-e, a print in horizontal or "landscape" format

-

On the shore of the Sumida River

-

Mt Fuji from the Sumida

-

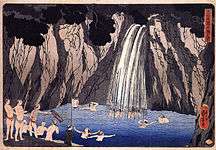

Pilgrims in the waterfall

Single sheet format

-

Banners for boys' day festival

-

Courtesan in training

-

Takeda Nobushige from the series 24 Generals of Kai Province

-

from the series Heroes of Our Country's Suikoden

-

from the series Heroes of Our Country's Suikoden

-

Hanagami Danjo no jo Arakage fighting a giant salamander

-

Miyamoto Musashi[1] killing a giant lizard

-

Saito Oniwakamaru, the young Benkei, fights the giant carp at the Bishimon waterfall

-

Hatsuhana doing penance under the Tonosawa waterfall

-

Keyamura Rokusuke under the Hikosan Gongen waterfall

-

_(1827%E2%80%931830).jpg)

Portrait of Chicasei Goyô (Wu Yong) (1827–1830)

- ^ Nussbaum, "Miyamoto Musashi" in p. 650., p. 650, at Google Books

- ^ Nussbaum, "Kakinomoto no hitomaro" in p. 456., p. 456, at Google Books

Themes

Kuniyoshi's work may be parsed thematically, as in this group of images which feature cats.

|

|

|

Caricatures were among Kuniyoshi's themes.

-

Scribbling on the storehouse wall

-

At first glance he looks very fierce, but he is actually a kind person

The Monster's Chūshingura (Bakemono Chūshingura), ca. 1836, Princeton University Art Museum

-

%2C_ca._1836_(a).jpg)

Acts 9-11 of the Kanadehon Chūshingura with act nine at top right, act ten at bottom right, act eleven, scene 1, at top left, act eleven, scene 2 at bottom left

-

%2C_ca._1836_(b).jpg)

Acts 5-8 of the Kanadehon Chūshingura with act five at top right, act six at bottom right, act seven at top left, act eight at bottom left

-

%2C_ca._1836_(c).jpg)

Acts 1-4 of the Kanadehon Chūshingura with act one at top right, act two at bottom right, act three at top left, act four at bottom left

See also

Notes

- ↑ Ōkubo, Junichi (1994), "Utagawa Kuniyoshi", Asashi Nihon rekishi jinbutsu jiten (朝日日本歴史人物事典), Tokyo, Japan: Asahi Shimbun Company, ISBN 4023400521

- 1 2 Nussbaum, Louis Frédéric et al (2005). "Kuniyoshi" in Japan Encyclopedia, p. 576., p. 576, at Google Books

- 1 2 3 Nussbaum, "Utagawa-ryū" in p. 1018., p. 1018, at Google Books

- 1 2 Lubow, Arthur. "Everything But the Robots: A Kuniyoshi Retrospective Reveals the Roots of Manga," New York Magazine. March 7, 2010.

- ↑ Robinson (1961), p. 5

- ↑ Johnson, Ken. "Epics and Erotica From a Grandfather of Anime," New York Times. April 15, 2010.

- ↑ "Yōshū Chikanobu [obituary]," Miyako Shimbun, No. 8847, October 2, 1912. p. 195.

References

- Kitagawa, Hiroshi and Burce T. Tsuchida, ed. (1975). The Tale of the Heike. Tokyo: University of Tokyo Press. ISBN 0-86008-128-1 OCLC 164803926

- Nussbaum, Louis Frédéric and Käthe Roth. (2005). Japan Encyclopedia. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-01753-5; OCLC 48943301

- Utagawa, Kuniyoshi; Robert A Rorex and Victoria Rovine. (1997). Samurai Stories: Woodblock Prints of Ichiyusai Kuniyoshi, from a Private Collection. Iowa City, Iowa: University of Iowa Museum of Art. OCLC 37678997

Further reading

- Forbes, Andrew ; Henley, David (2012). Forty-Seven Ronin: Utagawa Kuniyoshi Edition. Chiang Mai: Cognoscenti Books. ASIN: B00ADQM8II

- Merlin C. Dailey, David Stansbury, Utagawa Kuniyoshi: An Exhibition of the Work of Utagawa Kuniyoshi Based on the Raymond A. Bidwell Collection of Japanese Prints at the Springfield Museum of Fine Arts (Museum of Fine Arts, Springfield, 1980)

- Merlin C. Dailey, The Raymond A. Bidwell Collections of Prints by Utagawa Kuniyoshi (Museum of Fine Arts, Springfield, 1968) Note: completely different volume from the preceding

- Klompmakers, Inge, “Kuniyoshi’s Tattooed Heroes of the Suikoden”, Andon, No. 87, 2009, pp. 18–26.

- B. W. Robinson, Kuniyoshi (Victoria and Albert, London, 1961)

- B. W. Robinson, Kuniyoshi: The Warrior Prints (Cornell University, Ithaca, 1982) contains the definitive listing of his prints

- Robert Schaap, Timothy T. Clark, Matthi Forrer, Inagaki Shin'ichi, Heroes and Ghosts: Japanese Prints By Kuniyoshi 1797-1861 (Hotei, Leiden, 1998) is now the definitive work on him

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Utagawa Kuniyoshi. |

- Utagawa Kuniyoshi's Cats

- Kuniyoshi Project

- Utagawa Kuniyoshi Online

- Ukiyo-e Caricatures 1842-1905 Database of the Department of East Asian Studies of the University of Vienna. Over 400 prints of Kuniyoshi are included.

- Short biography at Artelino

- Graphic Heroes, Magic Monsters Gallery exhibition at New York's Japan Society featuring Kuniyoshi prints.