Lingerhahn

| Lingerhahn | ||

|---|---|---|

|

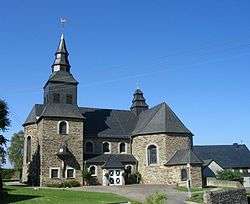

Church | ||

| ||

Lingerhahn | ||

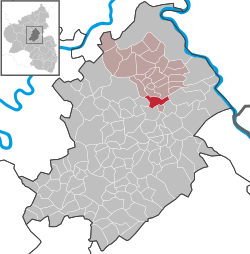

Location of Lingerhahn within Rhein-Hunsrück-Kreis district  | ||

| Coordinates: 50°5′44″N 7°33′57″E / 50.09556°N 7.56583°ECoordinates: 50°5′44″N 7°33′57″E / 50.09556°N 7.56583°E | ||

| Country | Germany | |

| State | Rhineland-Palatinate | |

| District | Rhein-Hunsrück-Kreis | |

| Municipal assoc. | Emmelshausen | |

| Government | ||

| • Mayor | Andreas Nick | |

| Area | ||

| • Total | 6.01 km2 (2.32 sq mi) | |

| Population (2015-12-31)[1] | ||

| • Total | 450 | |

| • Density | 75/km2 (190/sq mi) | |

| Time zone | CET/CEST (UTC+1/+2) | |

| Postal codes | 56291 | |

| Dialling codes | 06746 | |

| Vehicle registration | SIM | |

Lingerhahn is an Ortsgemeinde – a municipality belonging to a Verbandsgemeinde, a kind of collective municipality – in the Rhein-Hunsrück-Kreis (district) in Rhineland-Palatinate, Germany. It belongs to the Verbandsgemeinde of Emmelshausen, whose seat is in the like-named town.

Geography

Location

The municipality lies in the central Hunsrück between Emmelshausen and Kastellaun, right on the Schinderhannes-Radweg (cycle path) and not far from the Autobahn A 61 (Pfalzfeld interchange).

Climate

Yearly precipitation in Lingerhahn amounts to 758 mm, which falls into the middle third of the precipitation chart for all Germany. At 54% of the German Weather Service’s weather stations, lower figures are recorded. The driest month is February. The most rainfall comes in June. In that month, precipitation is 1.6 times what it is in February. Precipitation varies only slightly. Only at 4% of the weather stations are lower seasonal swings recorded.

History

Roman times

North of Lingerhahn in 1873, in the cadastral area known as “Mohr”, remnants of a Roman villa rustica were unearthed. These remnants amounted to “plates made of fired clay as well as clay pipes and remnants of ashes”,[2] although according to witnesses, coins were also found. Right nearby, a road, which had already existed before Roman times, led from the Rhine to the Moselle (today’s Hauptstraße, continuation: “Karrenstraße”).[3][4]

Middle Ages

In 1245, Lingerhahn had its first documentary mention: “Cunradus und Friedericus von Liningerhagen” cropped up as witnesses in a trial.[5] It can also be gathered from this document that Lingerhahn then belonged to the parish of Halsenbach.

By 1275, though, Lingerhahn belonged to the parish of Schönenberg (Sconinburg). This parish was named after a hill (hence the ending —berg, although this word is usually taken to mean “mountain”) between Kisselbach, Riegenroth and Steinbach upon which the parish church stood. At this time, the tithe lord was Hermann von Milewalt. He had been granted the tithing rights by the collegiate chapter at Saint Martin’s in Worms against payment of yearly interest (“15 Cologne solidi”).[6]

In 1375, there was a tour of inspection in the greater parish of Boppard, to which the parish of Schönenberg belonged. In the description of this event, the Imperial notary Detmarus von Langenbeke from Cologne noted that the Hunsrück region was found to be widely devastated; whole villages were empty.[7] This was, of course, the upshot from the Black Death, which was rife in Europe in the mid 14th century. According to chroniclers, more than a fourth of the Hunsrück’s population died of this sickness.[8]

As a reward for his help in electing the German king, Baldwin of Luxembourg acquired in 1309, 1312 and 1314, first from his brother Emperor Henry VII of Luxembourg and later from Louis the Bavarian the Imperial cities of Boppard and Wesel (now Oberwesel) and the Gallscheider Gericht (“Gallscheid Court”) at Emmelshausen as a pledge.[9] The judicial zone of the Gallscheid Court, named after an execution place within Emmelshausen’s limits – Galgenscheid or Galgenhöhe, the first six letters of each being German for “gallows” – encompassed a great area, within which was, among other places, Lingerhahn. In the Court’s 1460 boundary description, Lingerhahn was described as Linyngerhane slacken. This epithet slacken, which means “slags”, might well have meant the rubble mounds that can still be found today about a kilometre east of Lingerhahn (to the left before the Pfalzfeld turnoff on Landesstraße [State Road] 214/216). These are indeed slag heaps from the ore mining and smelting that was once done here. In 1435, Peter and Johann von Schöneck were enfeoffed with the court district.[10]

Destruction in the Thirty Years’ War and reconstruction

In the Thirty Years' War (1618-1648), Lingerhahn was occupied by troops of the Swedish king Gustav II Adolf and all but utterly destroyed by them as well.[8] In the nearby village of Pfalzfeld, the Schultheiß reported food and livestock thefts and destruction of crops by soldiers. Another eyewitness spoke of abuses and murders.[8] The war’s far-reaching consequences can be seen in Lingerhahn’s population figures: in 1563, Lingerhahn was home to 18 families (or family “heads”, at least),[11] whereas by 1663, there were only seven.[8]

After the destruction, the village had to be built all over again from the ground up. This was done at a new location. The village’s original site is described in the Lingerhahn school chronicle as being “more easterly”. Another clue about the old village comes from the cadastral toponym “Im Weiher”. This is a rural area some 200 m north of Lingerhahn on the road to Hausbay. The name means “In the Pond”, and it could refer to the old village’s fire pond.

Modern times

In 1784, Lingerhahn had 36 citizens.[12] In 1798, the Rhineland was annexed to the French Republic. The former administrative divisions, the Princely Electorates and Counties, were swept away and replaced with newly created départements. These were subdivided into arrondissements, which in turn were subdivided into cantons. Lingerhahn was grouped into the canton of Saint Goar in the Department of Rhin-et-Moselle. After the agreements concluded at the Congress of Vienna in 1815, the Rhineland was ceded to the Kingdom of Prussia and Lingerhahn then belonged to the Bürgermeisterei (“Mayoralty”) of Pfalzfeld in the newly created district of Sankt Goar in the Regierungsbezirk of Coblenz (as it was then spelt).[13]

Troubles in March 1848

The Year of Revolution – namely 1848 – did not pass Lingerhahn by. On the morning of 25 March 1848, it was reported to Mayor Müller that parishioners from Lingerhahn, “where there are many poor people and pedlars”,[14] were preparing to storm the mayor’s office in Pfalzfeld. He called his security watch together and had the men armed with rifles. Gendarmes from neighbouring places also hurried to help. At 14:00, the Lingerhahners appeared, armed with pistols and rifles, led by a rider on a white horse, which was supposed to represent Napoleon. Behind him were the Lingerhahn parish priest’s brother and brother-in-law as well as a few members of the parish council. Thereafter came the armed “army force” and at the end some women with empty baskets. Calls such as Vivat Napoleon! and Vivat die Republik! became loud.

When the mayor asked them what they wanted, they answered “Freedom and equality. There exists no more Prussian state. We hereby secede from the Mayoralty.” There ensued a brawl from which some came away wounded, some badly, and during which Prussian symbols, such as official signs and two Sovereign Eagles, were torn down.

Then, with a threat that they would come back at night with reinforcements, the armed crowd withdrew. Pfalzfeld was put under the protection of a division of the 26th Infantry Regiment and remained unmolested, while Lingerhahn once again formally seceded from Prussia, proclaimed a republic and no longer reported events that by law they had to report, such as births and deaths. Punishing these wayward people was out of the question owing to low troop strength. It was simply hoped that the impending work needing to be done in the fields would bring the citizens back to their senses.[14][15][16][17] Nothing further is known about this event. It seems that nothing much else happened.

These insurrectionists might well have meant to destroy the mayor’s office, and thereby all the deeds – particularly the land survey – as well, whereupon they would then have divided the land up among themselves. They might also have hoped for plundered booty.

The instigators of this small uprising seem to have been Father Schmoll, the Lingerhahn priest, and his brother, who had already drawn attention to himself by speaking out against the state. One remark that he is known to have made was: “already about 6 or 7 March it came out in Cologne that there was a religious war, that everybody should stick together.” The district chairman commented on a report of this in the margin: “Father Schmoll […] is notorious, not seldom from drinking, for his habit of being eccentric.”.[18]

This, as well as yearning for Imperial times or the French Republic, can all likely be traced back to regional disputes in which denominational motives surely played a great role. The formerly Electoral-Trier, thoroughly Catholic Lingerhahn was bigger, and therefore in its own people’s opinion at least, more important than Pfalzfeld with its mixture of denominations and its two-fifths Protestant minority, who with their likewise former allegiance to Hesse tended rather to look towards the Evangelical Sankt Goar.[19]

Politics

Municipal council

The council is made up of 8 council members, who were elected by majority vote at the municipal election held on 7 June 2009, and the honorary mayor as chairman.[20]

Mayor

Lingerhahn’s mayor is Andreas Nick, and his deputies are Thomas Kreis and Waltraud Schweitzer.[21]

Coat of arms

The German blazon reads: Über erhöhtem goldenen Schildfuß, darin ein roter Balken, in Grün durch einen silbernen Pfahl gespalten, vorne eine silberne Kapelle, hinten eine silberne Mauer mit einer sprudelnden Quelle.

The municipality’s arms might in English heraldic language be described thus: Per fess abased vert an endorse between a chapel affronty and a wall on top of which a spring issuant from which a stream of water, all argent, and Or a fess gules.

The base of the arms refers to the former Gallscheider Gericht (“Gallscheid Court”) through the arms then borne by the Lords of Schöneck (“Or a fess gules”, or a red horizontal stripe on a gold field). The chapel represents the first, thatched, church mentioned in the municipality’s 1719 stock book.[22] The wall stands for the quarrystone and brick cellar walls of a Roman villa within municipal limits. The spring supposedly furnished water for those who lived in this building and was only channelled into a drain in the 1950s. The endorse (narrow vertical stripe) symbolizes Karrenstraße, a road in the municipality that has existed since pre-Roman times.[23]

Culture and sightseeing

Buildings

The following are listed buildings or sites in Rhineland-Palatinate’s Directory of Cultural Monuments:[24]

- Saint Sebastian’s Catholic Parish Church (Pfarrkirche St. Sebastian), Ringstraße 34 – quarrystone aisleless church, design 1913/1914, architect Ludwig Becker, Mainz, building undertaken 1923/1924, transept-like smaller hall marked 1773

References

- ↑ "Gemeinden in Deutschland mit Bevölkerung am 31. Dezember 2015" (PDF). Statistisches Bundesamt (in German). 2016.

- ↑ Jahrbücher des Vereins von Alterthumsfreunden im Rheinlande, Heft LIII und LIV, Bonn 1873, S. 314.

- ↑ J. Hagen: Römerstraßen der Rheinprovinz II, Bonn 1931, S. 384, 434–436

- ↑ H. Eiden: Zur Siedlungs- und Kulturgeschichte der Frühzeit; in: F. J. Heyen: Zwischen Rhein und Mosel – Der Kreis St. Goar; S. 25.

- ↑ K. E. Demandt: Regesten der Grafen von Katzenelnbogen, (Veröffentlichungen der Historischen Kommission für Nassau, Bd. 119.), Wiesbaden 1953, Nr. 95, 98, 100, 295.

- ↑ H. Goerz: Mittelrheinische Regesten oder chronologische Zusammenstellung des Quellenmaterials für die Geschichte der Territorien der beiden Regierungsbezirke Koblenz und Trier in kurzen Auszügen, Band 4, Koblenz 1876/86, S. 35 f.

- ↑ Landeshauptarchiv Koblenz, Best. 74, Nr. 65. (Link)

- 1 2 3 4 W. Stoffel, E. Müller: Chronik des Hunsrückdorfes Lingerhahn, Lingerhahn 2009.

- ↑ Landeshauptarchiv Koblenz, Best. 133, Nr. 187. (Link)

- ↑ Elmar Rettinger: Historisches Ortslexikon Rheinland-Pfalz. Band 2: Ehemaliger Kreis St. Goar, Stichwort Gallscheid (PDF; 29,5 KB).

- ↑ Landeshauptarchiv Koblenz, Best. 1C, Nr. 12928. (Link)

- ↑ Wirtschaftsbuch des Antonius Schweitzer (1740), im Besitz der Familie Schweitzer, Lingerhahn

- ↑ Friedrich von Restorff: Topographisch-Statistische Beschreibung der Königlich Preußischen Rheinprovinzen, Berlin und Stettin 1830, S. 598. (PDF; 68,4 MB)

- 1 2 Landeshauptarchiv Koblenz, Best. 441 Nr. 1329 Bl. 545 ff. (Link)

- ↑ Landeshauptarchiv Koblenz, Best. 441 Nr. 3056 Bl. 42 f. (Link)

- ↑ Landeshauptarchiv Koblenz, Best. 403 Nr. 17332. (Link)

- ↑ Kreuznacher Zeitung Nr.43 (29. März 1848)

- ↑ Landeshauptarchiv Koblenz, Best. 441 Nr. 3056 Bl. 13. (Link)

- ↑ Paul Schmidt: Die ersten zwanzig Jahre konstitutionellen Lebens. 1848–1867; in: Franz Josef Heyen: Zwischen Rhein und Mosel – Der Kreis St. Goar, S. 481 f.

- ↑ Kommunalwahl Rheinland-Pfalz 2009, Gemeinderat

- ↑ Lingerhahn’s council

- ↑ Landeshauptarchiv Koblenz, Best. 1C, Nr. 14796. (Link)

- ↑ Description and explanation of Lingerhahn’s arms

- ↑ Directory of Cultural Monuments in Rhein-Hunsrück district

External links

- Lingerhahn in the collective municipality’s webpages (German)

- Municipality’s official webpage (German)

.jpg)