List of demolished places of worship in Brighton and Hove

In the city of Brighton and Hove, on the English Channel coast of Southeast England, more than 40 former places of worship—many with considerable architectural or townscape merit—have been demolished, for reasons ranging from declining congregations to the use of unsafe building materials. Brighton and Hove was granted city status in 2000 after being designated a unitary authority three years earlier through the merger of the fashionable, long-established seaside resort of Brighton[1] and the mostly Victorian residential town of Hove.[2] In both towns, and in surrounding villages and suburbs, a wide range of Christian churches were established—mostly in the 19th and early 20th centuries. More than 150 of these survive (although not all are still in religious use), but demolition and the redevelopment of sites for residential and commercial use has been happening since the 1920s. Postwar trends of declining church attendance and increasing demands for land accelerated the closure and destruction of church buildings: many demolitions were carried out in the 1950s and 1960s, and five churches were lost in 1965 alone. Although most of these buildings dated from the urban area's strongest period of growth in the 19th century, some newer churches have also been lost: one survived just 20 years.

Brighton and Hove's religious history

The former fishing village of Brighthelmston, with its hilltop parish church dedicated to St Nicholas,[3] experienced steady growth from the mid-18th century as its reputation as a fashionable resort grew. More chapels and churches were founded as the seasonal and permanent population grew; one of the first was linked to the Countess of Huntingdon's Connexion, a Methodist-based sect whose stronghold was the county of Sussex (which Brighton was part of). The first chapel on the site, founded in 1761, was the Connexion's first church in England.[4] A Baptist chapel of 1788 in Bond Street, the predecessor of Salem Strict Baptist Chapel (demolished 1974), was the first of many places of worship for that denomination in the Brighton area.[5] Neighbouring Hove, which also had an ancient parish church (dedicated to St Andrew), in turn began to thrive, and churches of many denominations were built as its population rose.

Reverend Henry Michell Wagner was the Anglican vicar of Brighton for much of the 19th century. His son Reverend Arthur Wagner was also an important part of religious life in the town throughout his adult life.[6] Both men were rich, charitably minded and proactive, and they established a series of churches in poor parts of Brighton to make Anglican worship more widely accessible in a town where pew rental (a requirement to pay to worship) was still an established practice. In 1824, when Henry Michell Wagner's tenure began, there were about 3,000 free places in the town's churches, but about 20,000 people were considered poor enough to need them.[6] Between them, the Wagners funded 11 new churches in densely populated lower-class areas of Brighton, which contributed to the near-doubling of Anglican church provision in Brighton in a 25-year period of the mid-19th century.[7] By the postwar period, as people moved to new suburbs and rising land values in central Brighton encouraged the replacement of houses with commercial and entertainment buildings, many of these churches were no longer needed. Six of the eleven Wagner churches were demolished: only two of Arthur Wagner's six survive, along with three of his son's five.[6]

The Roman Catholic community lost two churches without replacement within less than 10 years in outlying parts of the urban area. The large council estate of Whitehawk was developed from the 1930s to the 1960s and extensively rebuilt between 1975 and 1988.[8] In response to this growth, St John the Baptist's Roman Catholic church established a small Mass centre, dedicated to St Louis of France, on the estate in 1964. It was in use for just 18 years because it was built with high-alumina cement, a dangerous material which often made buildings structurally unsound.[9][10] The building was demolished in 1984.[9] Eight years later, residents of Portslade (a former urban district which became part of Hove in 1974) lost their 80-year-old church when the site was redeveloped for housing.[11]

Displaced congregations

The former parishes of several demolished Anglican churches were absorbed into those of neighbouring churches, which the displaced worshippers then joined. St Michael and All Angels Church in the Clifton Hill area took in the former parish of All Saints Church on Compton Avenue.[12] The parish of All Souls Church, which served a densely populated part of Kemptown around Eastern Road until extensive urban renewal and road widening took place in the 1960s, became part of nearby St Mary the Virgin's parish.[12] This had already received former members of St James's Church, which was lost in the 1950s.[13] When the Diocese of Chichester decided that the seafront area immediately to the east (around the original Kemp Town estate which gave the wider area its name) could no longer support both St George's Church and the smaller St Anne's Church, the latter was sold for demolition and redevelopment (although some internal fittings were retrieved) and the congregation joined St George's.[14] St Patrick's Church in Hove took in former worshippers at Christ Church, just across the boundary in the Montpelier area of Brighton, after an arson attack led to the latter's closure and demolition.[15] The Church of the Holy Resurrection, the first Anglican church to close in Brighton, joined the parish of its near neighbour St Paul's; the building was in commercial use for many years before its demolition.[15] The parishes of St Matthew's Church in the Queen's Park area and St Saviour's Church in Round Hill were absorbed by two churches—St Mark's and St Augustine's respectively—which have subsequently closed.[16][17]

The congregations of some other former churches also officially joined other church communities. When the Roman Catholic church of Our Lady Star of the Sea and St Denis in Portslade closed in 1992, the Diocese of Arundel and Brighton merged its parish with that of Southwick, a town in the neighbouring district of Adur.[11] St Theresa of Lisieux's Church, built in 1955 for Southwick's Roman Catholics,[18] served both towns thereafter. The closure in 1943 of Preston Park Methodist Church (demolished in 1974) led to its worshippers joining the Stanford Avenue Methodist Church on the other side of the park.[19] The merger in 1972 of the Congregational Church, the Presbyterian Church of England and several other denominations to form the United Reformed Church resulted in overcapacity in both Hove and Brighton. At Hove, the former St Cuthbert's Congregational Church became redundant in the early 1980s when services were consolidated at the Cliftonville Congregational Church (later renamed Central United Reformed Church);[20][21] and in Brighton, the Union Chapel on Air Street was sold to office developers to pay for a new multi-purpose building, the Brighthelm Church and Community Centre, in the nearby grounds of Hanover Chapel.[7][22] This early 19th-century building had housed a Presbyterian community, the Queen's Road Presbyterian Church, since 1847; but it was dilapidated and, because of the Congregational–Presbyterian merger, surplus to requirements.[23]

Demolished places of worship

| Name | Denomination | Area | Completed | Demolished | Present use of site | Notes | Refs |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All Saints Church | Anglican | Seven Dials 50°49′50″N 0°08′39″W / 50.8306°N 0.1443°W |

1853 | 1957 | Residential (White Lodge) | Richard Cromwell Carpenter designed this flint and stone church in the Decorated Gothic style for Reverend Henry Michell Wagner. He commissioned it to serve the rapidly developing residential streets of West Hill and Seven Dials, whose growth had been stimulated by the opening of the railway line to London. Work was meant to start in 1847, but prolific local builder George Cheeseman junior eventually constructed it in the early 1850s. The church had a seven-bay nave with north and south aisles, a turreted corner tower and a separate church hall, which survives behind the present block of flats. World War II bomb damage hastened its closure. | [12][24] [25][26] |

| All Souls Church | Anglican | Kemptown 50°49′16″N 0°07′36″W / 50.8211°N 0.1267°W |

1838 | 1968 | Residential (Miles Court) | This was the first church planned and endowed by Reverend Henry Michell Wagner. Intended to serve the poor area which had developed west of the high-class Kemp Town estate, it was founded in 1833 and consecrated in 1834; building work continued for four years. Henry Mew's stuccoed Neoclassical building, with a small clock tower, pedimented entrances and Tuscan pilasters, was remodelled by local architect Edmund Scott in 1879, and Charles Eamer Kempe added stained glass after 1900. Urban renewal and the planned widening of Eastern Road caused the church's demise. | [25][26] [27][28] [29] |

| Christ Church | Anglican | Montpelier 50°49′28″N 0°09′12″W / 50.8245°N 0.1534°W |

1837 | 1982 | Residential (Christ Church House) | Another of Wagner's churches, this Gothic Revival structure was designed by George Cheeseman junior—architect of several Brighton churches. Its spire, atop a short tower with dominant pinnacles, was identical to that at Chichester Cathedral. It was consecrated in 1838 and restored by Edmund Scott in 1886. Other features included galleries and a clerestory. The interior was destroyed by an arson attack on 29 August 1978. The church was declared redundant on 1 January 1981, and despite pleas to preserve the exterior the whole structure was bulldozed in 1982. The double-fronted International/Modern-style Christ Church House was built in its place in 1985–87. | [26][30] [31][32] [33][34] [35] |

| Church of the Holy Resurrection | Anglican | Brighton 50°49′21″N 0°08′47″W / 50.8226°N 0.1463°W |

1876 | 1968 | Commercial (Churchill Square shopping centre) | One of five churches founded by Henry Michell Wagner's son Arthur, this had a short life: it closed in 1908 and was used by the West Street Brewery and (from 1912) for meat storage. The site is now hidden under the Churchill Square development of 1963–72 (rebuilt 1996–98). Richard Herbert Carpenter's red-brick Early English design made little impression from street level because the building was almost completely underground; it was commonly known as "The Underground Church". | [15][26] [36][37] |

| St Alban's Church | Anglican | Coombe Road 50°50′23″N 0°07′08″W / 50.8398°N 0.1188°W |

1910 | 2013 | Residential | Lacy W. Ridge built this church between 1910 and 1914 to serve the Coombe Road suburb east of Lewes Road—an area historically known as East Preston. It became part of the Parish of the Resurrection in 1974, with the churches of St Martin, St Luke and St Wilfrid, and was closed on 22 November 2006. Demolition and replacement with houses were authorised in February 2013. | [35][38] [39][40] [41] |

| St Anne's Church | Anglican | Kemptown 50°49′08″N 0°07′27″W / 50.8190°N 0.1242°W |

1863 | 1986 | Residential (St Anne's Court) | Sheltered housing now stands on the site of Wagner's last church, which served a mostly middle-class area near Brighton seafront. The Decorated Gothic-style stone church was the work of prolific architect Benjamin Ferrey. The flamboyant John Nixon Memorial Hall, built nearby in 1912 and converted into flats in 2002, was its church hall. The single-aisle nave and chancel had a clerestory above. Services ceased in 1983, and the church was declared redundant from 1 July of that year. | [14][35] [42][43] [44] |

| St James's Church | Anglican | Kemptown 50°49′15″N 0°07′56″W / 50.8207°N 0.1322°W |

1875 | 1950 | Commercial (Co-op) | A chapel with the same dedication, built in 1810 and used for Anglican worship from 1826, was replaced by Edmund Scott's brick, flint and stone Early English-style church. It was hidden from the road behind shops and could be reached only along a narrow passage. John Purchas, curate from 1866, controversially introduced Ritualist practices at services; he was prosecuted for this, and banned for a year by the Bishop of Chichester. After its demolition in September 1950, some fixtures went to St Mary the Virgin Church, and a side chapel there was dedicated to St James. | [13][44] [45] |

| St Margaret's Church | Anglican | Brighton 50°49′22″N 0°08′55″W / 50.8227°N 0.1487°W |

1824 | 1959 | Residential (Sussex Heights) | Extravagant local businessman Barnard Gregory commissioned one of Brighton's leading architects, Charles Busby, to design a proprietary chapel for him in an area of Brighton he was trying to encourage fashionable, high-class people to visit. Gregory named the Greek Revival/Neoclassical church after his wife rather than the saint. The stuccoed building, with its Ionic portico and cupola, has been called Busby's best church and the finest of its style in Brighton. The gigantic Sussex Heights tower block was built in its place after declining congregations led to its closure. The modern Christ the King Church in Patcham received some of the fittings. | [46][47] [48][49] [50] |

| St Mary & St Mary Magdalene's Church | Anglican | North Laine 50°49′30″N 0°08′27″W / 50.8251°N 0.1407°W |

1862 | 1963 | Commercial (Sovereign House) | Only a tiny stub of Bread Street, where this church was built, survives: the rest was lost under the large headquarters of International Factors (later GMAC Commercial Finance). Arthur Wagner founded the church in a very poor, densely populated part of Brighton which had developed in the 1810s. George Frederick Bodley's Early English design used red brick and included a timber-framed ceiling, and has been called "modest" but "of distinction". It closed in 1948. Part of the dedication survives: when a barn was converted into a church in Coldean, a postwar housing estate on the edge of Brighton, in 1955, it was named St Mary Magdalene's and had some internal fittings transferred to it. | [48][51] [52][53] [54] |

| St Matthew's Church | Anglican | Queen's Park 50°49′24″N 0°07′15″W / 50.8233°N 0.1207°W |

1881 | 1967 | Residential (St Matthew's Court) | John Norton designed this large concrete, flint and stone church in the Early English style. It replaced a tin tabernacle and was consecrated in 1883. The large nave was flanked by narrow aisles, and a planned tower was left as a partly built stub. A mission chapel, the Bute Mission Hall, was founded nearby; this building (of 1893, by W.H. Nash) survives, but is now in commercial use. The church, on the corner of Sutherland Road and College Road, closed in 1962 and was demolished five years later. | [16][48] [55][56] |

| St Saviour's Church | Anglican | Round Hill 50°50′10″N 0°08′02″W / 50.8360°N 0.1339°W |

1886 | 1983 | Residential (St Saviour's Court) | Edmund Scott and F.T. Cawthorn's Early English-style church served middle-class housing around Ditchling Road. It was set below street level on a slope. Stone dressings complemented the flint and brick exterior. Inside, the main feature was an enormous reredos depicting the Ascension of Jesus, originally designed for Chichester Cathedral and brought to the church in 1904. The former Christ Church Independent Chapel became St Saviour's Mission Hall in 1920 and served the parish for 41 years. Declining congregations caused the church to close in 1981; it was formally declared redundant from 1 November 1980. | [17][35] [57][58] [59] |

| Adullam Chapel | Baptist | Brighton 50°49′26″N 0°08′34″W / 50.8240°N 0.1428°W |

1840 | c. 1920 | Commercial (Regent Cinema; later Boots the Chemist) | John Austin from the Providence Chapel in Church Street founded this in 1840. It was later called Windsor Street Chapel, and spent 40 years in religious use until a fire wrecked it in 1880. The building was only demolished in about 1920 when a 3,000-capacity "super-cinema", the Regent (demolished in 1974 for a Boots store), was built on the site. | [60][61] [62] |

| Ebenezer Strict Baptist Chapel | Baptist | Carlton Hill 50°49′37″N 0°07′57″W / 50.8269°N 0.1326°W |

1825 | 1966 | Residential (Normanhurst) | This opened on 13 April 1825 near the bottom of Richmond Street (now Richmond Parade), Brighton's steepest road. It was stuccoed and in the Renaissance style. The area underwent extensive redevelopment in the 1960s: seven 11-storey blocks of flats replaced the old buildings and street patterns. A new church of the same name, in modern Vernacular style and on a different site nearby, replaced the original building; this has in turn been demolished and rebuilt as a combined church and residential building. | [62][63] [64] |

| Horeb Tabernacle | Baptist | Preston Park 50°50′43″N 0°08′41″W / 50.8452°N 0.1447°W |

1917 | c. 1980 | Residential (Florence Court) | Also known as Preston Park Baptist Church, this brick chapel stood near the northeast corner of the park. It was demolished to make way for a block of flats. | [62] |

| Mighell Street Hall | Baptist | Carlton Hill 50°49′22″N 0°07′57″W / 50.8227°N 0.1325°W |

1878 | c. 1965 | Commercial (Amex House) | Founded by Thomas Boxall or George Virgo of Bethel Chapel, Wivelsfield (sources disagree) as a Strict Baptist chapel, this building became the parish hall of nearby St John the Evangelist's Church in 1910. It later housed a Spiritualist church, but when the new Brighton National Spiritualist Church was built on Edward Street in the mid-1960s, it was demolished. The forecourt of American Express's 300,000-square-foot (28,000 m2) European headquarters was built on the site of Mighell Street in 1977. | [59][63] [65][66] [67] |

| Moulsecoomb Way Baptist Church | Baptist | Moulsecoomb 50°51′05″N 0°06′31″W / 50.8513°N 0.1085°W |

1953 | 1988 | Leisure centre | This was built on the Moulsecoomb estate in 1953 and registered for marriages in 1956, but was said to be derelict at the time of its compulsory purchase by the council, who wanted to build Moulsecoomb Leisure Centre on the site. | [68][69] [70] |

| Portslade Baptist Chapel | Baptist | Portslade 50°49′53″N 0°12′45″W / 50.8314°N 0.2126°W |

1882 | 1960 | Commercial | A.R. Parr designed the local Baptist community's first church, which they occupied until 1959. Their move to a new church in South Street, in the old village area, was completed in 1961. The old building on Chapel Place, registered for marriages between March 1882 and October 1960, had prominent paired stair turrets and was Gothic Revival in style. | [71][72] |

| Providence Baptist Chapel | Baptist | Hove 50°49′51″N 0°10′25″W / 50.8308°N 0.1736°W |

1868 | c. 1980 | Commercial | Ebenezer Turquand, a member of the Salem Chapel in Brighton, extended Strict Baptist worship into neighbouring Hove by founding this chapel on a small street near St Andrew's Church. Named Providence Chapel by 1880, it was last recorded as a place of worship in 1908, although the building was later used for other purposes. | [73][74] [75] |

| Salem Strict Baptist Chapel | Baptist | Brighton 50°49′24″N 0°08′25″W / 50.8232°N 0.1402°W |

1861 | 1974 | Commercial (Edge House) | Brighton's first Baptist chapel, founded by members of Bethel Strict Baptist Chapel at Wivelsfield, was built on the site in 1787. Its capacity rose to 800 when it was enlarged in 1825; then in 1861 it was demolished and rebuilt by architect Thomas Simpson in a Neoclassical/Italianate style, with Doric columns at the entrance, flintwork and stuccoed walls. The original building was registered for marriages in 1837; this registration ran continuously until its cancellation in March 1972. | [5][63] [62][75] [76][77] |

| Stoneham Road Baptist Church | Baptist | Aldrington 50°50′06″N 0°11′14″W / 50.8350°N 0.1872°W |

1904 | 2008 | Residential (Poets Place) | Clayton & Black built this church of red brick in 1904, but it now has a roughcast exterior and was extended in 1931. It started as a mission church with assistance from Holland Road Baptist Church. A planning application to demolish it and build housing was withdrawn in 2004, but a new application was granted in 2008 and it was closed and demolished in that year. | [73][78] [79][80] [81][82] |

| Sussex Street Strict Baptist Chapel | Baptist | Carlton Hill 50°49′32″N 0°08′04″W / 50.8255°N 0.1345°W |

c. 1867 | 1937 | Commercial (Circus Street Municipal Market) | This stuccoed church with lancet windows was built in a slum area at the west end of Sussex Street (a section now called Morley Street). The densely packed houses were cleared in the 1930s by Brighton Corporation, who laid out mixed-use development in their place. The chapel, which closed in 1895 and became the mission hall to St Margaret's Church, was removed at the same time. Its founder, George Isaacs, was a member of the Salem Chapel in Bond Street. | [62][83] [84][85] |

| Tabernacle Strict Baptist Chapel | Baptist | Brighton 50°49′21″N 0°08′41″W / 50.8224°N 0.1447°W |

1834 | 1965 | Religious (Wagner Hall) | Architectural features of this Neoclassical building included a pediment and a stuccoed exterior. After a period of disuse, it was demolished during the Churchill Square redevelopment and replaced with the Wagner Hall, used as the church hall of the neighbouring St Paul's. | [62][83] |

| Brethren Meeting Room | Brethren | Patcham 50°52′02″N 0°09′09″W / 50.8672°N 0.1526°W |

1965 | 2012 | Vacant | The concrete-walled, flat-roofed building which stood at the northern edge of Patcham until November 2012 was built in 1965 for 750 worshippers. It was owned by the Sussex Vale Gospel Hall Trust, who submitted a planning application for its demolition in 2011 following the construction of a new gospel hall in the village of Albourne for the area's Exclusive Brethren worshippers. Nine houses will be built on the vacant site. The meeting room's marriage registration was cancelled in October 2012. | [86][87] [88][89] |

| Hollingbury Hall | Brethren | Hollingdean 50°50′37″N 0°07′54″W / 50.8435°N 0.1316°W |

1932 | 2007 | Residential | The building dated from 1932 but was registered as a place of worship in 1947. It was used by Brethren and later by an Evangelical organisation called Christian Fellowship. It closed in 1999 after several years of decline, and the building fell into dereliction. Two new houses and a community centre were built on the site. | [90][91] [92] |

| Stretton Hall | Brethren | Aldrington 50°50′07″N 0°12′09″W / 50.8354°N 0.2025°W |

a.-1963 | 2015 | Vacant | This small Vernacular-style building closed in the early 21st century and passed into commercial use. Its registration for worship was formally cancelled in December 2009. In 1963, it was identified as being the "city room" (main Brethren place of worship) in the Brighton area. | [93][94][95] |

| Winton Gospel Hall | Brethren | Rottingdean 50°48′46″N 0°03′44″W / 50.8127°N 0.0623°W |

c. 1950 | 2010 | Residential | A single-storey meeting room for Exclusive Brethren was built on the Falmer Road and registered for marriages in November 1950. It had a hipped roof and roughcast walls. It closed in about 2003, and planning permission for its demolition was granted in 2009. | [96][97] [98][99] |

| Central Free Church (Union Church) | Congregational | Brighton 50°49′27″N 0°08′38″W / 50.8243°N 0.1438°W |

1853 | 1984 | Commercial (Queen Square House) | Described as having "fine townscape value" (but, to Pevsner, "a restless group"), this large Early English-style stone church was in the commercial heart of Brighton on a corner site. Its sale to developers raised enough money to build a substantial new building (the Brighthelm Centre) on land nearby. Architectural firm James & Brown designed the church; a proposed tower was never built, but the building was renovated and extended in 1867 and 1884. The church hosted Baptist, Congregational and (from 1908) Free Church worshippers before reverting to Congregationalism in 1948. Its final name, from 1973 until closure in 1983, was the Central Free Church. The offices and shop units on the site were built in 1985–87. | [22][100] [7][101] [102] |

| London Road Congregational Church | Congregational | New England Quarter 50°49′49″N 0°08′14″W / 50.8303°N 0.1371°W |

1830 | 1976 | Residential | This Neoclassical building by William Simpson was endowed by local solicitor Henry Brooker, and was used by the Countess of Huntingdon's Connexion until 1881. Features included a wide pediment, large pilasters and a Venetian Gothic door. Thomas Simpson extended the church in 1856–57, but from 1874 the giant St Bartholomew's Church towered over it. Religious worship ceased in 1958, and the building was used for storage before being demolished in 1976 when the area was redeveloped with modern terraced houses and green space. | [55][103] [56][104] |

| The Dials Congregational Church | Congregational | Montpelier 50°49′44″N 0°08′50″W / 50.8290°N 0.1471°W |

1870 | 1972 | Residential (Homelees House) | A 150-foot (46 m) "Rhenish helm"-topped clock tower dominated this church and the skyline, forming one of Brighton's most prominent landmarks until its demolition in April 1972. Its large, horseshoe-shaped auditorium was another unusual feature. Thomas Simpson was responsible for the Romanesque Revival design. The church closed in 1969, and after demolition the site was vacant until work on Homelees House began in 1985. | [62][105] [106][107] |

| Connaught Christian Fellowship (New Life Church) | Evangelical | Round Hill 50°50′09″N 0°07′30″W / 50.8359°N 0.1249°W |

1897 | 2010 | Vacant | This red-brick and terracotta building had many uses, both religious and secular, before finally falling into dereliction by 2003. It faced Lewes Road and Melbourne Street, and had entrances in both. It was originally an institute for soldiers and manual workers, with a library, surgery, educational facilities and bar. Later religious uses included an Anglican mission hall and the New Life Centre, run by an Evangelical group. Planning permission for its demolition was granted in November 2009. | [55][108] [109][110] |

| Immanuel Community Church | Evangelical | Hanover 50°49′43″N 0°07′34″W / 50.8286°N 0.1262°W |

1881 | 2003 | Residential (Immanuel House) | This began as a Primitive Methodist chapel. In 1893 it was turned into the Islingword Road Mission Chapel, which was previously housed in a tin tabernacle. Later, a non-denominational church was established in the red-brick, arched-windowed building. A fire destroyed the church in 2003, and it was quickly replaced by flats with an integrated community hall and nursery. The congregation joined that of the former Elim Pentecostal church in Preston Park, whose building was also demolished, and became the Immanuel Family Church. They met at St Augustine's Church then the former Christ the King Church in Patcham (now called the Fountain Centre). | [111][112] |

| The Downs Free Church | Evangelical | Woodingdean 50°50′17″N 0°04′33″W / 50.8380°N 0.0759°W |

1932 | 1991 | Residential | This church stood on Downsway, and opened during the early stages of Woodingdean's suburban development. It was extended later in the 20th century, and was in use until 1991. The congregation now meets as the Downs Baptist Church in the local primary school. | [113][114] |

| Norfolk Road Methodist Church | Methodist | Montpelier 50°49′32″N 0°09′17″W / 50.8256°N 0.1548°W |

1868 | 1965 | Residential (Braemar House) | This large church of flint and stone had much stained glass and a turret-style tower at one corner. C.O. Ellison of Liverpool was the architect responsible for the Early English/Decorated Gothic design. Nicknamed "The Methodist Cathedral of the South", it closed in 1964 after demographic changes caused the congregation to dwindle. Its marriage registration, granted in 1870, was cancelled in October of that year. | [102][115] [116][117] |

| Preston Park Methodist Church | Methodist | Preston Park 50°50′08″N 0°08′34″W / 50.8356°N 0.1428°W |

1883 | 1974 | Commercial (London Gate) | The Methodist community erected this church in 1883 on the site of a tin tabernacle which they had been using for worship. Bomb damage in 1943 caused the closure of the brick and terracotta Gothic Revival building, designed by C.O. Ellison. It stood empty until its demolition as part of the commercial redevelopment of the west side of London Road in the 1970s. | [19][102] |

| Sussex Street Primitive Methodist Chapel | Methodist | Carlton Hill 50°49′31″N 0°08′00″W / 50.8253°N 0.1333°W |

1836 | c. 1950 | Residential (Kingswood Flats) | One historian has identified this as the first Primitive Methodist place of worship in Sussex. It was a Classical-style stuccoed building with arched windows and topped with a pediment. The Sussex Street area was extensively redeveloped after World War II. | [102] |

| Christ Church Independent Chapel | Independent | New England Quarter 50°50′02″N 0°08′24″W / 50.8338°N 0.1400°W |

1874 | 1997 | Residential (Amber House) | J.G. Gibbins designed this church for an Independent congregation in 1874, but it had other religious uses and periods of closure before it finally fell out of use in the 1980s. Its charismatic founder John B. Haynes died in 1902, and the church lost impetus; it soon closed, but St Saviour's Church bought it in 1920 and turned it into a mission hall serving the surrounding streets. This closed in 1961, but two years later an Elim Pentecostal moved in and stayed for about 20 years. | [55][118] [119] |

| Grand Parade Chapel | Independent | Brighton 50°49′33″N 0°08′06″W / 50.8257°N 0.1351°W |

1835 | 1938 | Widened road | Attributed to George Cheeseman junior, designer of several churches in Brighton, this stuccoed Gothic Revival building housed Independent worshippers for its first few years before being taken on by the Catholic Apostolic Church (1853–65) and the Free Church of England later. After a period of secular use (as a concert hall), it was occupied by Plymouth Brethren between 1920 and 1935, when its marriage licence (under the name Grand Parade Hall) was revoked. That congregation moved to the Gordon Mission Hall in Kemptown at that time, and the Grand Parade building was demolished in 1938. | [120][121] [122] |

| Our Lady Star of the Sea & St Denis Church | Roman Catholic | Portslade 50°50′02″N 0°12′48″W / 50.8340°N 0.2132°W |

1912 | 1991 | Residential | The plain Romanesque Revival exterior of Portslade's Roman Catholic church, of roughcast and stone, contrasted with the extremely lavish Byzantine interior, decorated mostly by local artists. A tower at the west end housed an organ gallery and was topped with a spire. | [11][71] |

| St Louis, King of France Church | Roman Catholic | Whitehawk 50°49′04″N 0°06′14″W / 50.8177°N 0.1039°W |

1964 | 1984 | Residential (Henley Court) | This was a Mass centre (similar to a mission chapel) established on the Whitehawk housing estate by St John the Baptist's Church and served from it. The main building material was high-alumina cement, which was popular during the 1960s until it was found to cause structural defects. The building, which was registered for marriages in July 1964, was condemned as unsafe in 1982; the Diocese of Arundel and Brighton decided not to repair it as it would be too expensive. | [9][10] [123][124] |

| Goodwill Centre | Salvation Army | Moulsecoomb 50°51′08″N 0°06′17″W / 50.8521°N 0.1047°W |

c. 1936 | 1956 | Commercial | The Salvation Army established a hall on the Moulsecoomb estate in the 1930s, which was apparently run from the main Congress Hall at Park Crescent. Electrical engineering firm Allen West Ltd, Moulsecoomb's main employers in the mid-20th century, built a factory on the site in 1956. This in turn was demolished in favour of the Fairway Retail Park; the Beacon Bingo centre now occupies the site. | [125][126] [127] |

| Salvation Army Citadel | Salvation Army | Carlton Hill 50°49′21″N 0°08′00″W / 50.8225°N 0.1333°W |

1884 | 1965 | Widened road | This stuccoed building stood opposite the south end of Dorset Gardens and was distinguished by its large crow-stepped parapet with a battlement-topped tower at each end. It was deregistered for worship in November 1965. | [121][128] [129] |

| Providence Chapel | Calvinist | North Laine 50°49′33″N 0°08′24″W / 50.8257°N 0.1400°W |

1805 | 1965 | Commercial | This chapel, of polychromatic patterned brick and topped by a pediment, was founded by W.J. Brook, a follower of William Huntington. Many alterations were made during its 160-year existence. When this part of Church Street was redeveloped in the 1960s, the congregation moved to the former Nathaniel Reformed Episcopal church in West Hill. | [120][121] |

| Carlton Hill Apostolic Church | Catholic Apostolic | Carlton Hill 50°49′26″N 0°08′06″W / 50.8239°N 0.1349°W |

1865 | 1964 | Educational (extension of Brighton Art College) | Brighton's Catholic Apostolic community formed in the 1830s and occupied Grand Parade Chapel for 18 years, but moved to this new building in 1865. The Early English red-brick building had an apse at the west end. After it fell out of religious use in 1954, it was used by Brighton Art College for ten years to house students. | [55][60] |

| Countess of Huntingdon's Chapel | Countess of Huntingdon's Connexion | Brighton 50°49′21″N 0°08′24″W / 50.8226°N 0.1401°W |

1870 | 1972 | Commercial (Huntingdon House) | Three churches of this denomination occupied the site—its predecessors dated from 1761 and 1774—but John Wimble's stone and flint Early English-style building was the best known. Its "graceful" spire and "excellent" stained glass made it a landmark in central Brighton, but declining congregations and structural problems led to its demise: the spire had to be removed in 1969, three years after the church closed, as it was tilting. The land was originally Selina, Countess of Huntingdon's garden. | [4][55] [130][131] |

| Elim Balfour Road Church | Elim Pentecostal | Preston Park 50°50′50″N 0°08′21″W / 50.8471°N 0.1393°W |

1939 | 2007 | Residential | This small brick building on Balfour Road dated from 1939, although it was registered for marriages in 1954. It was demolished in 2007 after planning permission was granted for two houses to be built on the site. The former Church of Christ the King in nearby Patcham, a larger and better equipped building, had come up for sale, and the congregation of the Elim church bought it together with worshippers displaced from the former Immanuel Community Church. | [112][132] [133][134] [135] |

| Kingdom Hall | Jehovah's Witnesses | Southern Cross 50°50′06″N 0°12′52″W / 50.8350°N 0.2145°W |

c. 1950 | 2012 | Residential | This former Kingdom Hall in Portslade, on Trafalgar Road close to Fishersgate railway station, was opened in the 1950s, extended several times and sold to a screen printing company in 1991. Its registration was officially cancelled in May 1993. Planning permission for its demolition was granted in late 2012. | [136][137] [138] |

| Emmanuel Reformed Episcopal Church | Reformed Episcopal | Montpelier 50°49′37″N 0°09′15″W / 50.8269°N 0.1542°W |

1867 | 1965 | Religious (Montpelier Place Baptist Church) | Although a new church stands on the site of this grey Gothic Revival building, it is not a replacement building for the same congregation: instead, worshippers from the former Tabernacle Strict Baptist Chapel in Regency Road bought the vacant land and built new premises for themselves. The 1867 building has been attributed to S. Hemmings, and had a tower (topped with a spire) at the southeast corner. | [55][120] [139] |

| St Cuthbert's Church | United Reformed Church (Presbyterian) | Hove 50°49′54″N 0°09′37″W / 50.8318°N 0.1603°W |

1904 | 1984 | Residential (Bellmead) | This large church, by Edward Procter, formed a landmark on a corner site. His design was Decorated Gothic and used brick and stone with terracotta dressings. The church had a tower and spire. The congregation moved to the Cliftonville Congregational Church after it became a United Reformed Church. | [20][73] |

Gallery

- Pictures of demolished places of worship

The Immanuel Community Church in Hanover was destroyed by fire in 2003. Demolition is underway in this picture from May of that year.

The Immanuel Community Church in Hanover was destroyed by fire in 2003. Demolition is underway in this picture from May of that year..jpg) The Connaught Institute, formerly used by several religious groups, was demolished in 2010.

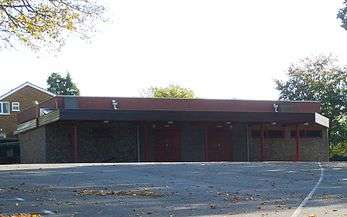

The Connaught Institute, formerly used by several religious groups, was demolished in 2010.- Stoneham Road Baptist Church in Aldrington (pictured in 2007) was closed and demolished in 2008.

The Exclusive Brethren meeting room at Patcham (pictured in 2011) was cleared in late 2012 for residential development.

The Exclusive Brethren meeting room at Patcham (pictured in 2011) was cleared in late 2012 for residential development. Around the same time, the former Jehovah's Witnesses Kingdom Hall at Southern Cross in Portslade (pictured in 2009 when in commercial use) was demolished for housing.

Around the same time, the former Jehovah's Witnesses Kingdom Hall at Southern Cross in Portslade (pictured in 2009 when in commercial use) was demolished for housing.- In 2015, another former Brethren meeting hall (pictured in 2010 when in use as a fitness centre) was demolished. It stood on Portland Road in Aldrington.

See also

- List of places of worship in Brighton and Hove

- List of demolished places of worship in East Sussex

- List of demolished places of worship in West Sussex

Media related to demolished places of worship in Brighton and Hove at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to demolished places of worship in Brighton and Hove at Wikimedia Commons

References

Notes

- ↑ Antram & Morrice 2008, p. 10.

- ↑ Antram & Morrice 2008, p. 3.

- ↑ Collis 2010, p. 323.

- 1 2 Collis 2010, p. 61.

- 1 2 Collis 2010, p. 274.

- 1 2 3 Collis 2010, p. 359.

- 1 2 3 Collis 2010, p. 261.

- ↑ Collis 2010, p. 368.

- 1 2 3 Shipley 2001, p. 24.

- 1 2 Collis 2010, p. 369.

- 1 2 3 Shipley 2001, p. 25.

- 1 2 3 Shipley 2001, p. 13.

- 1 2 Shipley 2001, pp. 16–17.

- 1 2 Shipley 2001, p. 14.

- 1 2 3 Shipley 2001, p. 15.

- 1 2 Shipley 2001, p. 19.

- 1 2 Shipley 2001, p. 20.

- ↑ Hudson, T. P. (ed) (1980). "A History of the County of Sussex: Volume 6 Part 1 – Bramber Rape (Southern Part). Southwick". Victoria County History of Sussex. British History Online. pp. 173–183. Retrieved 22 July 2010.

- 1 2 Shipley 2001, p. 32.

- 1 2 Shipley 2001, p. 31.

- ↑ Middleton 2002, Vol. 12, p. 77.

- 1 2 Shipley 2001, pp. 30–31.

- ↑ Dale 1989, p. 178.

- ↑ Collis 2010, p. 363.

- 1 2 Antram & Morrice 2008, p. 15.

- 1 2 3 4 Elleray 2004, p. 6.

- ↑ Shipley 2001, pp. 13–14.

- ↑ Nairn & Pevsner 1965, pp. 428–429.

- ↑ Collis 2010, pp. 107–108.

- ↑ Shipley 2001, pp. 14–15.

- ↑ Antram & Morrice 2008, p. 107.

- ↑ Shipley 2001, Picture 11.

- ↑ Nairn & Pevsner 1965, pp. 431–432.

- ↑ Collis 2010, p. 75.

- 1 2 3 4 "The Church of England Statistics & Information: Lists (by diocese) of closed church buildings as at October 2012" (PDF). Church of England. 1 October 2012. Archived from the original on 30 January 2013. Retrieved 30 January 2013.

- ↑ Antram & Morrice 2008, p. 16.

- ↑ Collis 2010, pp. 63–66.

- ↑ Carder 1990, §9.

- ↑ "Benefice of Brighton, The Resurrection". Diocese of Chichester website. Diocese of Chichester. 2008. Retrieved 2009-03-14.

- ↑ "Coombe Road, Brighton". John Whiting riba. 2013. Archived from the original on 11 March 2013. Retrieved 11 March 2013.

- ↑ "Planning Register: Application BH2012/01589". Brighton & Hove City Council planning application. Brighton & Hove City Council. 23 May 2012. Archived from the original on 11 March 2013. Retrieved 11 March 2013.

St Albans Church, Coombe Road, Brighton: Demolition of existing church and erection of 9no new dwellings comprising 1no 4 bed house, 3no 3 bed houses, 1no 2 bed flat and 4no 1 bed flats

- ↑ Collis 2010, p. 105.

- ↑ Antram & Morrice 2008, p. 134.

- 1 2 Elleray 2004, p. 7.

- ↑ Carder 1990, §167.

- ↑ Antram & Morrice 2008, p. 104.

- ↑ Antram & Morrice 2008, p. 124.

- 1 2 3 Elleray 2004, p. 8.

- ↑ Carder 1990, §149.

- ↑ Shipley 2001, pp. 17–18.

- ↑ Shipley 2001, p. 18.

- ↑ Collis 2010, p. 216.

- ↑ Collis 2010, p. 82.

- ↑ Antram & Morrice 2008, p. 188.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Elleray 2004, p. 12.

- 1 2 Nairn & Pevsner 1965, p. 434.

- ↑ Antram & Morrice 2008, p. 180.

- ↑ Carder 1990, §51.

- 1 2 Elleray 2004, p. 9.

- 1 2 Shipley 2001, p. 34.

- ↑ Collis 2010, p. 69.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Elleray 2004, p. 10.

- 1 2 3 Shipley 2001, p. 27.

- ↑ Collis 2010, p. 7.

- ↑ Collis 2010, p. 49.

- ↑ Collis 2010, p. 109.

- ↑ Chambers 1953, p. 27.

- ↑ Collis 2010, p. 206.

- ↑ The London Gazette: no. 40887. p. 5444. 25 September 1956. Retrieved 15 August 2012.

- ↑ Registered in accordance with the Places of Worship Registration Act 1855 (Number in Worship Register: 65366; Name: Moulsecoomb Way Baptist Church; Address: Moulsecoomb Way, Brighton; Denomination: Baptists). Retrieved 24 September 2012. (Archived version of list)

- 1 2 Elleray 2004, p. 45.

- ↑ The London Gazette: no. 42177. p. 7232. 25 October 1960. Retrieved 20 December 2012.

- 1 2 3 Elleray 2004, p. 35.

- ↑ Middleton 2002, Vol. 2, p. 9.

- 1 2 Chambers 1953, p. 19.

- ↑ Collis 2010, p. 215.

- ↑ The London Gazette: no. 45631. p. 3749. 27 March 1972. Retrieved 17 October 2012.

- ↑ Middleton 2002, Vol. 3, p. 70.

- ↑ "Holland Road Baptist Church: Rev. David Davies 1897–1907". Holland Road Baptist Church. Archived from the original on 23 February 2012. Retrieved 2 August 2013.

- ↑ The London Gazette: no. 58830. p. 14433. 22 September 2008. Retrieved 5 September 2012.

- ↑ "Brighton and Hove City Council: List of applications determined by the director of environment under delegated powers or in implementation of a previous committee decision". Brighton & Hove City Council planning applications. Brighton & Hove City Council. 15 December 2004.

- ↑ "Planning Register: Application BH2008/01456". Brighton & Hove City Council planning application. Brighton & Hove City Council. 23 April 2008. Archived from the original on 2 August 2013. Retrieved 2 August 2013.

- 1 2 Shipley 2001, p. 28.

- ↑ Collis 2010, p. 194.

- ↑ Collis 2010, pp. 4–6.

- ↑ "145 Vale Avenue, Brighton: Outline application with some matters reserved for demolition of existing building and erection of 9no dwellings with new access" (PDF). Brighton & Hove City Council Planning Application BH2011/02889. Brighton & Hove City Council. 26 September 2011. Retrieved 14 October 2011.

- ↑ "Planning statement in support of an application for demolition of existing building and redevelopment to provide nine houses at Brethren's Meeting Hall, 145 Vale Avenue, Patcham, Brighton BN1 8YF" (PDF). Brighton & Hove City Council Planning Application BH2011/02889. Brighton & Hove City Council. September 2011. Retrieved 14 October 2011.

- ↑ Registered in accordance with the Places of Worship Registration Act 1855 (Number in Worship Register: 71162; Name: Meeting Room; Address: 145 Vale Avenue, Patcham; Denomination: Christians not otherwise designated). Retrieved 24 September 2012. (Archived version of list)

- ↑ The London Gazette: no. 60307. p. 20330. 23 October 2012. Retrieved 30 May 2013.

- ↑ Registered in accordance with the Places of Worship Registration Act 1855 (Number in Worship Register: 53934; Name: Hollingbury Hall; Address: Adjoining 119 Hollingdean Terrace, Preston, Brighton; Denomination: Christians not otherwise designated). Retrieved 24 September 2012. (Archived version of list)

- ↑ "119A Hollingdean Terrace, Brighton, BN1 7HB: Proposed Demolition of Existing Buildings and Erection of Replacement Community/Church Centre with Associated Staff Flat and 2 Dwellings" (PDF). Brighton & Hove City Council Planning Application BH2005/01711/FP. Strutt & Parker. Retrieved 14 October 2011.

- ↑ Carder 1990, §76.

- ↑ "Plymouth Brethren Hall (Aldrington)". Sussex On-line Parish Clerks (OPC). 2010. Retrieved 24 May 2010.

- ↑ The London Gazette: no. 59305. p. 389. 13 January 2010. Retrieved 26 April 2012.

- ↑ Trowbridge, W.H. (1998–2012) [1963]. "List of Meetings Great Britain and Ireland – 1963". MyBrethren.org website (History and Ministry of the early "Exclusive Brethren" (so-called) – their origin, progress and testimony 1827–1959 and onward). Hampton Wick: The Stow Hill Bible and Tract Depot. Archived from the original on 19 January 2013. Retrieved 3 October 2012.

- ↑ Registered in accordance with the Places of Worship Registration Act 1855 (Number in Worship Register: 58943; Name: Winton Gospel Hall; Address: Falmer Road, Rottingdean; Denomination: Christians not otherwise designated). Retrieved 24 September 2012. (Archived version of list)

- ↑ "Planning Committee: Plans List (Wednesday 12th August 2009)" (PDF). Brighton & Hove City Council. 12 August 2009. pp. 78–95. Retrieved 14 October 2011.

- ↑ "Rottingdean Parish Council: The Annual Village Meeting" (PDF). Rottingdean Parish Council. 21 April 2011. p. 2. Retrieved 14 October 2011.

- ↑ The London Gazette: no. 39079. p. 5961. 28 November 1950. Retrieved 1 June 2012.

- ↑ Collis 2010, p. 39.

- ↑ Nairn & Pevsner 1965, p. 438.

- 1 2 3 4 Elleray 2004, p. 11.

- ↑ Shipley 2001, p. 30.

- ↑ Collis 2010, p. 185.

- ↑ Shipley 2001, p. 29.

- ↑ Antram & Morrice 2008, p. 178.

- ↑ Collis 2010, p. 74.

- ↑ Carder 1990, §87.

- ↑ "Planning Register: Application BH2009/02187". Brighton & Hove City Council planning application. Brighton & Hove City Council. 11 September 2009. Retrieved 25 July 2010.

- ↑ Registered in accordance with the Places of Worship Registration Act 1855 (Number in Worship Register: 32433; Name: Connaught Institute; Address: 131 Lewes Road, Brighton; Denomination: Undenominational). Retrieved 24 September 2012. (Archived version of list)

- ↑ Collis 2010, p. 144.

- 1 2 "Our History". Immanuel Family Church. 2010. Retrieved 22 July 2010.

- ↑ Carder 1990, §214.

- ↑ "The History of DBC". Downs Baptist Church. 2011. Retrieved 13 April 2016.

- ↑ Shipley 2001, p. 33.

- ↑ Hickman 2007, p. 62.

- ↑ The London Gazette: no. 43464. p. 8763. 16 October 1964. Retrieved 17 October 2012.

- ↑ Shipley 2001, p. 36.

- ↑ Registered in accordance with the Places of Worship Registration Act 1855 (Number in Worship Register: 69698; Name: Christ Church (Evangelical Centre); Address: New England Road, Preston, Brighton; Denomination: Evangelical Free). Retrieved 24 September 2012. (Archived version of list)

- 1 2 3 Shipley 2001, p. 37.

- 1 2 3 Elleray 2004, p. 13.

- ↑ The London Gazette: no. 34174. p. 4109. 25 June 1935. Retrieved 50 October 2012.

- ↑ Registered in accordance with the Places of Worship Registration Act 1855 (Number in Worship Register: 69645; Name: St Louis, King of France; Address: Henley Road, Whitehawk; Denomination: Roman Catholics). Retrieved 24 September 2012. (Archived version of list)

- ↑ The London Gazette: no. 43397. p. 6534. 31 July 1964. Retrieved 19 October 2012.

- ↑ Carder 1990, §120.

- ↑ Carder 1990, §105.

- ↑ Registered in accordance with the Places of Worship Registration Act 1855 (Number in Worship Register: 59029; Name: Salvation Army Hall; Address: Moulsecoomb Way, East Moulsecoomb; Denomination: Salvation Army). Retrieved 24 September 2012. (Archived version of list)

- ↑ Shipley 2001, p. 38.

- ↑ The London Gazette: no. 43824. p. 11122. 26 November 1965. Retrieved 6 July 2012.

- ↑ Shipley 2001, p. 35.

- ↑ Antram & Morrice 2008, p. 14.

- ↑ Collis 2010, p. 253.

- ↑ "Planning Register: Application BH2007/02325". Brighton & Hove City Council planning application. Brighton & Hove City Council. 15 June 2007. Retrieved 23 July 2010.

- ↑ The London Gazette: no. 40086. p. 647. 29 January 1954. Retrieved 15 May 2012.

- ↑ Registered in accordance with the Places of Worship Registration Act 1855 (Number in Worship Register: 64089; Name: Elim Church; Address: 142 Balfour Road, Brighton; Denomination: Elim Foursquare Gospel Alliance). Retrieved 24 September 2012. (Archived version of list)

- ↑ Middleton 2002, Vol. 8, p. 35.

- ↑ The London Gazette: no. 53308. p. 8829. 20 May 1993. Retrieved 4 April 2012.

- ↑ "Application for Planning Permission, Town and Country Planning Act 1990 (BH2011/03316)" (PDF). Brighton & Hove City Council planning application BH2011/03316. Brighton & Hove City Council. 31 October 2011. Retrieved 30 November 2012.

- ↑ Antram & Morrice 2008, p. 171.

Bibliography

- Antram, Nicholas; Morrice, Richard (2008). Brighton and Hove. Pevsner Architectural Guides. London: Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-12661-7.

- Carder, Timothy (1990). The Encyclopaedia of Brighton. Lewes: East Sussex County Libraries. ISBN 0-86147-315-9.

- Chambers, Ralph (1953). The Strict Baptist Chapels of England: Sussex. 2. Thornton Heath: Ralph Chambers.

- Collis, Rose (2010). The New Encyclopaedia of Brighton. (based on the original by Tim Carder) (1st ed.). Brighton: Brighton & Hove Libraries. ISBN 978-0-9564664-0-2.

- Dale, Antony (1989). Brighton Churches. London EC4: Routledge. ISBN 0-415-00863-8.

- Elleray, D. Robert (2004). Sussex Places of Worship. Worthing: Optimus Books. ISBN 0-9533132-7-1.

- Hickman, Michael R. (2007). A Story to Tell: 200 Years of Methodism in Brighton and Hove. Brighton: Brighton and Hove Methodist Circuit. ISBN 978-0-9556506-0-4.

- Middleton, Judy (2002). The Encyclopaedia of Hove & Portslade. Brighton: Brighton & Hove Libraries.

- Musgrave, Clifford (1981). Life in Brighton. Rochester: Rochester Press. ISBN 0-571-09285-3.

- Nairn, Ian; Pevsner, Nikolaus (1965). The Buildings of England: Sussex. Harmondsworth: Penguin Books. ISBN 0-14-071028-0.

- Shipley, Berys J.M. (2001). The Lost Churches of Brighton and Hove. Worthing: Optimus Books. ISBN 0-9533132-5-5.

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)