Literary Welsh morphology

The morphology of the Welsh language shows many characteristics perhaps unfamiliar to speakers of English or continental European languages like French or German, but has much in common with the other modern Insular Celtic languages: Irish, Scottish Gaelic, Manx, Cornish, and Breton. Welsh is a moderately inflected language. Verbs inflect for person, tense and mood with affirmative, interrogative and negative conjugations of some verbs. There are few case inflections in Literary Welsh, being confined to certain pronouns.

Modern Welsh can be written in two varieties – Colloquial Welsh or Literary Welsh. The grammar described on this page is for Literary Welsh.

Initial consonant mutation

- Soft mutation

- Nasal mutation

- Aspirate mutation

- Related article: Lenition

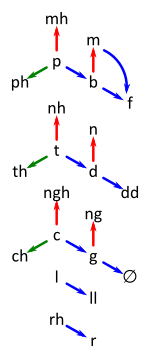

Initial consonant mutation is a phenomenon common to all Insular Celtic languages, although there is no evidence of it in the ancient Continental Celtic languages of the early first millennium. The first consonant of a word in Welsh may change depending on grammatical context (such as when the grammatical object directly follows the grammatical subject), when preceded by certain words, e.g. i, yn, and a or when the normal word order of a sentence is changed, e.g. Y mae tŷ gennyf, Y mae gennyf dŷ "I have a house". Welsh has three mutations: the soft mutation, the nasal mutation, and the aspirate mutation. These are also represented in writing:

Radical Soft Nasal Aspirate p b mh ph t d nh th c g ngh ch b f m d dd n g ∅* ng m f ll l rh r

A blank cell indicates no change.

For example, the word for "stone" is carreg, but "the stone" is y garreg (soft mutation), "my stone" is fy ngharreg (nasal mutation) and "her stone" is ei charreg (aspirate mutation).

*The soft mutation for g is the simple deletion of the initial sound. For example, gardd "garden" becomes yr ardd "the garden". But this can behave as a consonant under certain circumstances, e.g. "gellir" (one can) becomes "ni ellir" (one cannot) not "*nid ellir".

Soft mutation

The soft mutation (Welsh: treiglad meddal) is by far the most common mutation in Welsh. When words undergo soft mutation, the general pattern is that unvoiced plosives become voiced plosives, and voiced plosives become fricatives or disappear; some fricatives also change, and the full list is shown in the above table.

Common situations where the full soft mutation occurs are as follows – note that this list is by no means exhaustive:

- adjectives (and nouns used genitively as adjectives) qualifying feminine singular nouns

- words immediately following the prepositions am "for, about", ar "on", at "to", tan/dan "under", tros/dros "over", trwy/drwy "through", heb "without", hyd "until", gan "by", wrth "at", i "to, for", o "of, from"

- nouns used with the number two (dau / dwy)

- nouns following adjectives (N.B. most adjectives follow the noun)

- nouns after the possessives dy, informal singular "your", and ei when it means "his"

- an object of a simple verb

- the second element in many compound words

- when an adverbial phrase comes between two elements, the second element is mutated (e.g. rhaid mynd "it is necessary to go" becomes rhaid i mi fynd "it is necessary to me to go")

- verbs after the interrogative particle a (e.g. cerddaist "you walked", a gerddaist? "did you walk?")

In some cases a limited soft mutation takes place. This differs from the full soft mutation in that words beginning with rh and ll do not mutate.

Situations where the limited soft mutation occurs are as follows.

- feminine singular nouns with the definite article or the number one (un)

- nouns or adjectives used predicatively or adverbially after yn

- adjectives following cyn or mor, both meaning "so"

- after the prefixes can- and dar-

The occurrence of the soft mutation often obscures the origin of placenames to non-Welsh-speaking visitors. For example, Llanfair is the church of Mair (Mary), and Pontardawe is the bridge on the Tawe.

Nasal mutation

The nasal mutation (Welsh: treiglad trwynol) normally occurs:

- after fy "my" e.g. gwely "a bed", fy ngwely "my bed"

- after the locative preposition yn "in" e.g. Tywyn "Tywyn", yn Nhywyn "in Tywyn"

- after the negating prefix an-, e.g. teg "fair", annheg "unfair".

Notes

- The preposition yn becomes ym if the following noun (mutated or not) begins with m, and yng if the following noun begins with ng, e.g. Bangor "Bangor", ym Mangor "in Bangor", Caerdydd "Cardiff", yng Nghaerdydd "in Cardiff".

- In words beginning with an-, the n is dropped before the mutated consonant, e.g. an + personol "personal" → amhersonol "impersonal", although it is retained before a non-mutating letter, e.g. an + sicr "certain" → ansicr "uncertain", or if the resultant mutation allows for a double n, e.g. an + datod "undo" → annatod "integral". (This final rule does not apply to words that would potentially produce a cluster of four consonants, e.g. an + trefn "order" → anhrefn "disorder", not *annhrefn.)

Under nasal mutation, voiced plosives become voiced nasals, and unvoiced plosives become unvoiced nasals.

Pronunciation

The aspirated nasals may appear at first hard for English speakers to pronounce. However, in fact they are generally pronounced as an aspirated nasal followed by h, and this does not in practice result in a large cluster of consonant sounds because it is preceded either by the vowel ending of fy, or a form of yn where the -n is possibly replaced with -m or -ng to match the first letter of the mutated word. For example:

- fy + tadau → fy nhadau, pronounced as fyn hadau

- yn + Caerdydd → yng Nghaerdydd, pronounced as yng haerdydd

Grammatical considerations

Note that yn meaning "in" must be distinguished from other uses of yn which do not cause nasal mutation. For example:

- In the sentence Mae plastig yn nhrwyn Siaco, trwyn has undergone nasal mutation.

- In the sentence Mae trwyn Siaco yn blastig, plastig has undergone soft mutation, not nasal mutation.

- In the sentence Mae trwyn Siaco yn cynnwys plastig, cynnwys is not mutated.

Note also that the ’m form often used instead of fy after vowels does not cause nasal mutation. For example:

- Pleidiol wyf i'm gwlad. (not *i'm ngwlad)

Aspirate mutation

The aspirate mutation (Welsh: treiglad llaes) turns the unvoiced plosives into aspirated fricatives. It is easiest to remember based on an addition of an h in the spelling (c, p, t → ch, ph, th), although strictly speaking the resultant forms are single phonemes which happen to contain an h as the second character.

The aspirate mutation occurs:

- after the possessive ei when it means "her"

- after a "and"

- after â "with"

- for masculine nouns after the number three (tri)

- after the number six (chwech, written before the noun as chwe)

Mixed mutation

A mixed mutation occurs after the particles ni (before a vowel nid), na (before a vowel nad) and oni (before a vowel onid) which negate verbs. Initial consonants which change under the aspirate mutation do so; other consonants change as in the soft mutation (if at all). For example, clywais "I heard" is negated as ni chlywais "I did not hear", na chlywais "that I did not hear" and oni chlywais? "did I not hear?", whereas dywedais "I said" is negated as ni ddywedais, na ddywedais and oni ddywedais?.

The article

Welsh has no indefinite article. The definite article, which precedes the words it modifies and whose usage differs little from that of English, has the forms y, yr, and ’r. The rules governing their usage are:

- When the previous word ends in a vowel, regardless of the quality of the word following, ’r is used, e.g. mae'r gath tu allan ("the cat is outside"). This rule takes precedence over the other two below.

- When the word begins with a vowel, yr is used, e.g. yr arth "the bear".

- In all other places, y is used, e.g. y bachgen ("the boy").

Note that the letter w represents both a consonant /w/ and vowel /u/ and a preceding definite article will reflect this by following the rules above, e.g. y wal /ə ˈwal/ "the wall" but yr wy /ər ˈʊˑɨ/ or /ər ˈʊi/ "the egg". However, pre-vocalic yr is used before both the consonantal and vocalic values represented by i, e.g. yr iâr /ər ˈjaːr/ "the hen" and yr ing /ər ˈiŋ/ "the anguish". It is also always used before the consonant h, e.g. yr haf /ər ˈhaːv/ "the summer".

Is should also be noted that the first rule may be applied with greater or less frequency in various literary contexts. For example, poetry might use ’r more often to help with metre, e.g. ’R un nerth sydd yn fy Nuw "The same power is in my God" from a hymn by William Williams Pantycelyn. On the other hand, sometimes its use is more restricted in very formal contexts, e.g. Wele, dyma y rhai annuwiol "Behold, these are the ungodly" in Psalm 73.12.

The article triggers the soft mutation when it is used with feminine singular nouns, e.g. tywysoges "(a) princess" but y dywysoges "the princess".

Nouns

Like most other Indo-European languages, all nouns belong to a certain grammatical gender; in this case, masculine or feminine. A noun's gender conforms to its referent's natural gender when it has one, e.g. mam "mother" is feminine. There are also semantic, morphological and phonological clues to help determine a noun's gender, e.g. llaeth "milk" is masculine as are all liquids, priodas "wedding" is feminine because it ends in the suffix -as, and theatr "theatre" is feminine because the stressed vowel is an e. Many everyday nouns, however, possess no such clues.

Sometimes a noun's gender may vary depending on meaning, for example gwaith when masculine means "work", but when feminine, it means "occasion, time". The words for languages behave like feminine nouns (i.e. mutate) after the article, e.g. y Gymraeg "the Welsh language", but as masculine nouns (i.e. without mutation of an adjective) when qualified, e.g. Cymraeg da "good Welsh". The gender of some nouns depends on a user's dialect, and although in the literary language there is some standardization, some genders remain unstable, e.g. tudalen "page".

Welsh has two systems of grammatical number. Singular/plural nouns correspond to the singular/plural number system of English, although unlike English, Welsh noun plurals are unpredictable and formed in several ways. Some nouns form the plural with an ending (usually -au), e.g. tad and tadau. Others form the plural through vowel change, e.g. bachgen and bechgyn. Still others form their plurals through some combination of the two, e.g. chwaer and chwiorydd.

Several nouns have two plural forms, e.g. the plural of stori "story" is either storïau or straeon. This can help distinguish meaning in some cases, e.g. whereas llwyth means both "tribe" and "load", llwythau means "tribes" and llwythi means "loads".

The other system of number is the collective/unit system. The nouns in this system form the singular by adding the suffix -yn (for masculine nouns) or -en (for feminine nouns) to the plural. Most nouns which belong in this system are frequently found in groups, for example, plant "children" and plentyn "a child", or coed "forest" and coeden "a tree". In dictionaries, the plural is often given first.

Adjectives

Adjectives normally follow the noun they qualify, e.g. mab ieuanc "(a) young son", while a small number precede it, usually causing soft mutation, e.g. hen fab "(an) old son". The position of an adjective may even determine its meaning, e.g. mab unig "(a) lonely son" as opposed to unig fab "(an) only son". In poetry, however, and to a lesser extent in prose, most adjectives may occur before the noun they modify, but this is a literary device.[1] It is also seen in some place names, such as Harlech (hardd + llech)[2] and Glaslyn.

Attributively after feminine singular nouns, adjectives receive the soft mutation, for example, bach "small" and following the masculine noun bwrdd and the feminine noun bord, both meaning "table":

Masculine Feminine Singular bwrdd bach bord fach Plural byrddau bach bordydd bach

For the most part, adjectives are uninflected, though there are a few with distinct masculine/feminine and/or singular/plural forms. A feminine adjective is formed from a masculine by means of vowel change, usually "w" to "o" (e.g. crwn "round" to cron) or "y" to "e" (e.g. gwyn "white" to gwen). A plural adjective may employ vowel change (e.g. marw "dead" to meirw), take a plural ending (e.g. coch "red" to cochion) or both (e.g. glas "blue, green" to gleision).

Masculine Feminine Singular bwrdd brwnt bord front Plural byrddau bryntion bordydd bryntion

Adjective comparison in Welsh is fairly similar to the English system except that there is an additional degree, the equative (Welsh y radd gyfartal). Native adjectives with one or two syllables usually receive the endings -ed "as/so" (preceded by the word cyn in a sentence, which causes a soft mutation except with ll and rh: cyn/mor daled â chawr, "as tall as a giant"), -ach "-er" and -af "-est". The stem of the adjective may also be modified when inflected, including by provection, where final or near-final b, d, g become p, t, c respectively.

Positive Equative Comparative Superlative English tal taled talach talaf "tall" gwan gwanned gwannach gwannaf "weak" trwm trymed trymach trymaf "heavy" gwlyb gwlyped gwlypach gwlypaf "wet" rhad rhated rhatach rhataf "cheap" teg teced tecach tecaf "fair"

Generally, adjectives with two or more syllables use a different system, whereby the adjective is preceded by the words mor "as/so" (which causes a soft mutation except with ll and rh), mwy "more" and mwyaf "most".

Positive Equative Comparative Superlative English diddorol mor ddiddorol mwy diddorol mwyaf diddorol "interesting" cynaliadwy mor gynaliadwy mwy cynaliadwy mwyaf cynaliadwy "sustainable" llenyddol mor llenyddol mwy llenyddol mwyaf llenyddol "literary"

The literary language tends to prefer the use inflected adjectives where possible.

There are also a number of irregular adjectives.

Positive Equative Comparative Superlative English da cystal gwell gorau "good" drwg cynddrwg gwaeth gwaethaf "bad" mawr cymaint mwy mwyaf "big" bach cyn lleied llai lleiaf "small" hir hwyed hwy hwyaf "long" cyflym cynted cynt cyntaf "fast"

These are the possessive adjectives:

Singular Plural First Person fy (n) ein Second Person dy (s) eich Third Person Masculine ei (s) eu Feminine ei (a)

The possessive adjectives precede the noun they qualify, which is sometimes followed by the corresponding form of the personal pronoun, especially to emphasize the possessor, e.g. fy mara i "my bread", dy fara di "your bread", ei fara ef "his bread" etc.

Ein, eu and feminine ei add an h a following word beginning with a vowel, e.g. enw "name", ei henw "her name".

The demonstrative adjectives are inflected for gender and number:

Masculine Feminine Plural Proximal hwn hon hyn Distal hwnnw honno hynny

These follow the noun they qualify, which also takes the article. For example, the masculine word llyfr "book" becomes y llyfr hwn "this book", y llyfr hwnnw "that book", y llyfrau hyn "these books" and y llyfrau hynny "those books".

Pronouns

Personal pronouns

The Welsh personal pronouns are:

Singular Plural First Person (f)i, mi ni Second Person ti, di chwi, chi Third Person Masculine ef, fe hwy, hwynt, nhw Feminine hi

The Welsh masculine-feminine gender distinction is reflected in the pronouns. There is, consequently, no word corresponding to English "it", and the choice of e or hi depends on the grammatical gender of the antecedent.

The English dummy or expletive "it" construction in phrases like "it's raining" or "it was cold last night" also exists in Welsh and other Indo-European languages like French, German, and Dutch, but not in Italian, Spanish, Portuguese, or the Slavic languages. Unlike other masculine-feminine languages, which often default to the masculine pronoun in the construction, Welsh uses the feminine singular hi, thus producing sentences like:

- Mae hi'n bwrw glaw.

- It's raining.

- Yr oedd hi'n oer neithiwr.

- It was cold last night.

Notes on the forms

The usual third-person masculine singular form is ef in Literary Welsh. The form fe is used as an optional affirmative marker before a conjugated verb at the start of a clause, but may also be found elsewhere in modern writing, influenced by spoken Welsh.

The traditional third-person plural form is hwy, which may optionally be expanded to hwynt where the previous word does not end in -nt itself. Once more, modern authors may prefer to use the spoken form nhw, although this cannot be done after literary forms of verbs and conjugated prepositions.

Similarly, there is some tendency to follow speech and drop the "w" from the second-person plural pronoun chwi in certain modern semi-literary styles.

In any case, pronouns are often dropped in the literary language, as the person and number can frequently be discerned from the verb or preposition alone.

Ti vs. chwi

Chi, in addition to serving as the second-person plural pronoun, is also used as a singular in formal situations. Conversely, ti can be said to be limited to the informal singular, such as when speaking with a family member, a friend, or a child. This usage corresponds closely to the practice in other European languages. The third colloquial form, chdi, is not found in literary Welsh.

Reflexive pronouns

The reflexive pronouns are formed with the possessive adjective followed by hunan (plural hunain) "self".

Singular Plural First Person fy hunan ein hunain Second Person dy hunan eich hunain, eich hunan Third Person ei hunan eu hunain

Note that there is no gender distinction in the third person singular.

Reduplicated pronouns

Literary Welsh has reduplicated pronouns that are used for emphasis, usually as the subject of a focussed sentence. For example:

Tydi a'n creodd ni. "(It was) Thou that createdst us."

Oni ddewisais i chwychwi? "Did I not choose you?"

Singular Plural First Person myfi nyni Second Person tydi chwychwi Third Person Masculine efe hwynt-hwy Feminine hyhi

Conjunctive pronouns

Welsh has special conjunctive forms of the personal pronouns. They are perhaps more descriptively termed 'connective or distinctive pronouns' since they are used to indicate a connection between or distinction from another nominal element. Full contextual information is necessary to interpret their function in any given sentence.

Less formal variants are given in brackets. Mutation may also, naturally, affect the forms of these pronouns (e.g. minnau may be mutated to finnau)

Singular Plural First Person minnau, innau ninnau Second Person tithau chwithau Third Person Masculine yntau (fyntau) hwythau (nhwythau) Feminine hithau

The emphatic pronouns can be used with possessive adjectives in the same way as the simple pronouns are used (with the added function of distinction or connection).

Demonstrative pronouns

In addition to having masculine and feminine forms of this and that, Welsh also has separate set of this and that for intangible, figurative, or general ideas.

Masculine Feminine Intangible this hwn hon hyn that hwnnw, hwnna honno, honna hynny these y rhain those y rheiny

In certain expressions, hyn may represent "now" and hynny may represent "then".

Verbs

In literary Welsh, far less use is made of auxiliary verbs than in its colloquial counterpart. Instead conjugated forms of verbs are common. Most distinctively, the non-past tense is used for the present as well as the future.

The preterite, non-past (present-future), and imperfect (conditional) tenses have forms that are somewhat similar to colloquial Welsh, demonstrated here with talu 'pay'. Note the regular affection of the a to e before the endings -ais, -aist, -i, -ir and -id.

Singular Plural Preterite First Person telais talasom Second Person telaist talasoch Third Person talodd talasant Impersonal talwyd Non-Past First Person talaf talwn Second Person teli telwch Third Person tâl talant Impersonal telir Imperfect First Person talwn talem Second Person talit talech Third Person talai talent Impersonal telid

To these, the literary language adds pluperfect, subjunctive, and imperative tenses. Again, note the affection before -wyf and -wch.

Singular Plural Pluperfect First Person talaswn talasem Second Person talasit talasech Third Person talasai talasent Impersonal talasid Subjunctive First Person talwyf talom Second Person telych taloch Third Person talo talont Impersonal taler Imperative First Person (does not exist) talwn Second Person tala telwch Third Person taled talent Impersonal taler

Irregular verbs

Bod and compounds

Bod 'to be' is highly irregular. Compared with the inflected tenses above, it has separate present and future tenses, separate present and imperfect subjunctive tenses, separate imperfect and conditional tenses, and uses the pluperfect as a consuetudinal imperfect (amherffaith arferiadol) tense. The third person of the present tense has separate existential (oes, no plural because plural nouns take a singular verb) and descriptive (yw/ydyw, ŷnt/ydynt) forms, except in the situations where the positive (mae, maent) or relative (sydd) forms are used in their place.

Singular Plural Preterite First Person bûm buom Second Person buost buoch Third Person bu buont Impersonal buwyd Future First Person byddaf byddwn Second Person byddi byddwch Third Person bydd byddant Impersonal byddir Present First Person wyf, ydwyf ŷm, ydym Second Person wyt, ydwyt ych, ydych Third Person yw, ydyw; oes; mae; sydd ŷnt, ydynt; maent Impersonal ys; ydys Singular Plural Imperfect First Person oeddwn oeddem Second Person oeddit oeddech Third Person oedd, ydoedd oeddynt, oeddent Impersonal oeddid Conditional First Person buaswn buasem Second Person buasit buasech Third Person buasai buasent Impersonal buasid Consuetudinal Imperfect First Person byddwn byddem Second Person byddit byddech Third Person byddai byddent Impersonal byddid Singular Plural Present Subjunctive First Person bwyf, byddwyf bôm, byddom Second Person bych, byddych boch, byddoch Third Person bo, byddo bônt, byddont Impersonal bydder Imperfect Subjunctive First Person bawn baem Second Person bait baech Third Person bai baent Impersonal byddid Imperative First Person (does not exist) byddwn Second Person bydd byddwch Third Person bydded, boed, bid byddent Impersonal bydder

In less formal styles, the affirmative/indirect relative (y(r)), interrogative/direct relative (a), and negative (ni(d)) particles have a particularly strong tendency to become infixed on the front of forms of bod, for instance roedd and dyw for yr oedd and nid yw. Although the literary language tends toward keeping the particles in full, affirmative y is optional before mae(nt).

Reduplicating the negation of the verb with ddim (which in the literary language strictly means "any" rather than "not") is generally avoided.

Certain other verbs with bod in the verb-noun are also to some extent irregular. By far the most irregular are gwybod ("to know (a fact)") and adnabod ("to recognize/know (a person)"); but there also exists a group of verbs that alternate -bu- (in the preterite and pluperfect) and -bydd- (in all other tenses) stems, namely canfod ("to perceive"), cydnabod ("to acknowledge"), cyfarfod ("to meet"), darfod ("to perish"), darganfod ("to discover"), gorfod ("to be obliged"), and hanfod ("to descend/issue from").

Therefore presented below are gwybod and adnabod in the tenses where they do not simply add gwy- or adna- to forms of bod. Note that they both, like bod, separate the present and future tenses. Note the devoicing of b to p before the subjunctive endings, a regular feature of this mood.

Singular Plural Present First Person gwn gwyddom Second Person gwyddost gwyddoch Third Person gŵyr gwyddant Impersonal gwyddys Imperfect First Person gwyddwn gwyddem Second Person gwyddit gwyddech Third Person gwyddai gwyddent Impersonal gwyddid Present Subjunctive First Person gwypwyf, gwybyddwyf gwypom, gwybyddom Second Person gwypych, gwybyddych gwypoch, gwybyddoch Third Person gwypo, gwybyddo gwypont, gwybyddont Impersonal gwyper, gwybydder Imperfect Subjunctive First Person gwypwn, gwybyddwn gwypem, gwybyddem Second Person gwypit, gwybyddit gwypech, gwybyddech Third Person gwypai, gwybyddai gwypent, gwybyddent Impersonal gwypid, gwybyddid Imperative First Person (does not exist) gwybyddwn Second Person gwybydd gwybyddwch Third Person gwybydded gwybyddent Impersonal gwybydder Singular Plural Present First Person adwaen adwaenom Second Person adwaenost adwaenoch Third Person adwaen, edwyn adwaenant Impersonal adwaenir Imperfect First Person adwaenwn adwaenem Second Person adwaenit adwaenech Third Person adwaenai adwaenent Impersonal adwaenid Subjunctive First Person adnapwyf, adnabyddwyf adnapom, adnabyddom Second Person adnepych, adnabyddych adnapoch, adnabyddoch Third Person adnapo, adnabyddo adnapont, adnabyddont Impersonal adnaper, adnabydder Imperative First Person (does not exist) adnabyddwn Second Person adnebydd adnabyddwch Third Person adnabydded adnabyddent Impersonal adnabydder

Mynd, gwneud, cael, and dod

The four verbs mynd "to go", gwneud "to do", cael "to get", and dod "to come" are all irregular. These share many similarities, but there are also far more points of difference in their literary forms than in their spoken ones. In particular, cael is significantly different from the others in the preterite and non-past tenses and is unusual for having no imperative mood.

mynd gwneud cael dod Singular Plural Singular Plural Singular Plural Singular Plural Preterite First Person euthum aethom gwneuthum gwnaethom cefais cawsom deuthum daethom Second Person aethost aethoch gwnaethost gwnaethoch cefaist cawsoch daethost daethoch Third Person aeth aethant gwnaeth gwnaethant cafodd cawsant daeth daethant Impersonal aethpwyd, aed gwnaethpwyd, gwnaed cafwyd, caed daethpwyd, deuwyd, doed Non-past First Person af awn gwnaf gwnawn caf cawn deuaf, dof deuwn, down Second Person ei ewch gwnei gwnewch cei cewch deui, doi deuwch, dewch, dowch Third Person â ânt gwna gwnânt caiff cânt daw deuant, dônt Impersonal eir gwneir ceir deuir, doir Imperfect First Person awn aem gwnawn gwnaem cawn caem deuwn, down deuem, doem Second Person ait aech gwnait gwnaech caet caech deuit, doit deuech, doech Third Person âi aent gwnâi gwnaent câi caent deuai, dôi deuent, doent Impersonal eid gwneid ceid deuid, doid Pluperfect First Person aethwn, elswn aethem, elsem gwnaethwn, gwnelswn gwnaethem, gwnelsem cawswn cawsem daethwn daethem Second Person aethit, elsit aethech, elsech gwnaethit, gwnelsit gwnaethech, gwnelsech cawsit cawsech daethit daethech Third Person aethai, elsai aethent, elsent gwnaethai, gwnelsai gwnaethent, gwnelsent cawsai cawsent daethai daethent Impersonal aethid, elsid gwnaethid, gwnelsid cawsid daethid (Present) Subjunctive First Person elwyf elom gwnelwyf gwnelom caffwyf caffom delwyf delom Second Person elych eloch gwnelych gwneloch ceffych caffoch delych deloch Third Person êl, elo elont gwnêl, gwnelo gwnelont caffo caffont dêl, delo delont Impersonal eler gwneler caffer deler Imperfect Subjunctive First Person elwn elem gwnelwn gwnelem caffwn, cawn caffem, caem (Same as Imperfect) (Same as Imperfect) Second Person elit elech gwnelit gwnelech caffit, cait caffech, caech (Same as Imperfect) (Same as Imperfect) Third Person elai elent gwnelai gwnelent caffai, câi caffent, caent (Same as Imperfect) (Same as Imperfect) Impersonal elid gwnelid ceffid, ceid (Same as Imperfect) Imperative First Person (none) awn (none) gwnawn (none) (none) (none) deuwn, down Second Person dos ewch gwna gwnewch (none) (none) tyr(e)d deuwch, dewch, dowch Third Person aed, eled aent, elent gwnaed, gwneled gwnaent, gwnelent (none) (none) deued, doed, deled deuent, doent, delent Impersonal aer, eler gwnaer, gwneler (none) deuer, doer, deler

Prepositions

In Welsh, prepositions frequently change their form when followed by a pronoun. These are known as inflected prepositions. They fall into three main conjugations.

Firstly those in -a- (at, am (stem: amdan-), ar, tan/dan):

Singular Plural First Person ataf atom Second Person atat atoch Third Person Masculine ato atynt Feminine ati

Secondly those in -o- (er, heb, rhag, rhwng (stem: rhyng-), tros/dros, trwy/drwy (stem: trw-/drw-), o (stem: ohon-), yn). All apart from "o" add a linking element in the third person (usually -dd-, but -ydd- in the case of trwy/drwy, and -t- in the case of tros/dros):

Singular Plural First Person erof erom Second Person erot eroch Third Person Masculine erddo erddynt Feminine erddi

Thirdly, those in -y- (gan and wrth). Gan includes both vowel changes and a linking element, whilst wrth has neither:

Singular Plural First Person gennyf gennym Second Person gennyt gennych Third Person Masculine ganddo ganddynt Feminine ganddi

Finally, the preposition "i" is highly irregular:

Singular Plural First Person imi, im inni, in Second Person iti, it ichwi Third Person Masculine iddo iddynt Feminine iddi

All inflected prepositions may optionally be followed by the appropriate personal pronouns, apart from "i", where this is only possible in the third person, thanks to its proper endings in the other persons sounding the same as the pronouns. In slightly less formal Welsh, the endings are split off the first and second persons of "i" to be interpreted as pronouns instead, although this creates the anomalous pronoun "mi".

The majority of prepositions (am, ar, at, gan, heb, hyd, i, o, tan/dan, tros/dros, trwy/drwy, wrth) trigger the soft mutation. The exceptions are â, gyda, and tua, which cause the aspirate mutation; yn, which causes the nasal mutation; and cyn, ger, mewn, rhag, and rhwng, which do not cause any mutation.

Notes

- ↑ A Comprehensive Welsh Grammar, David A. Thorne, Blackwell, 1993. p.135

- ↑ Oxford Dictionary of British Place Names by Anthony David Mills, Oxford University Press 1991

References

- Jones, Morgan D. A Guide to Correct Welsh (Llandysul: Gomer, 1976). ISBN 0-85088-441-1.

- King, G. (2003). Modern Welsh. Oxford: Routledge. ISBN 0-415-28270-5

- Lewis, D. Geraint. Y Llyfr Berfau (Llandysul: Gomer, 1995). ISBN 978-1-85902-138-5.

- Thomas, Peter Wynn. Gramadeg y Gymraeg (Cardiff: UWP, 1996). ISBN 0-7083-1345-0.