Lolita (1962 film)

| Lolita | |

|---|---|

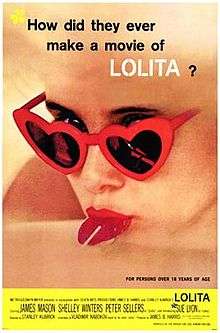

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Stanley Kubrick |

| Produced by | James B. Harris |

| Screenplay by |

|

| Based on |

Lolita by Vladimir Nabokov |

| Starring | |

| Music by |

|

| Cinematography | Oswald Morris |

| Edited by | Anthony Harvey |

Production company |

|

| Distributed by | Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer |

Release dates |

|

Running time | 152 minutes |

| Country |

|

| Language | English |

| Budget | $2 million |

| Box office | $9.25 million[2] |

Lolita is a 1962 British-American black comedy-drama film[3] directed by Stanley Kubrick based on the novel of the same title by Vladimir Nabokov, about a middle-aged man who becomes obsessed with a teenage girl. The film stars James Mason as Humbert Humbert, Sue Lyon as Dolores Haze (Lolita), and Shelley Winters as Charlotte Haze, with Peter Sellers as Clare Quilty.

Owing to the MPAA's restrictions at the time, the film toned down the more provocative aspects of the novel, sometimes leaving much to the audience's imagination. The actress who played Lolita, Sue Lyon, was 14 at the time of filming. Kubrick later commented that, if he had realized how severe the censorship limitations were going to be, he probably never would have made the film.

Plot

Set in the 1950s, the film begins in medias res near the end of the story, with a confrontation between two men: one of them, Clare Quilty, drunk and incoherent, plays Chopin's Polonaise in A major, Op. 40, No. 1 on the piano before being shot from behind a portrait painting of a young woman. The shooter is Humbert Humbert, a 40-something British professor of French literature.

The film then flashes back to events four years earlier. Humbert arrives in Ramsdale, New Hampshire, intending to spend the summer before his professorship begins at Beardsley College, Ohio. He searches for a room to rent, and Charlotte Haze, a cloying, sexually frustrated widow, invites him to stay at her house. He declines until seeing her daughter, Dolores, affectionately called "Lolita". Lolita is a soda-pop drinking, gum-snapping, overtly flirtatious teenager, with whom Humbert becomes infatuated.

To be close to Lolita, Humbert accepts Charlotte's offer and becomes a lodger in the Haze household. But Charlotte wants all of "Hum's" time for herself and soon announces she will be sending Lolita to an all-girl sleepaway camp for the summer. After the Hazes depart for camp, the maid gives Humbert a letter from Charlotte, confessing her love for him and demanding he vacate at once unless he feels the same way. The letter says that if Humbert is still in the house when she returns, Charlotte will know her love is requited, and he must marry her. Though he roars with laughter while reading the sadly heartfelt yet characteristically overblown letter, Humbert marries Charlotte.

Things turn sour for the couple in the absence of the nymphet: glum Humbert becomes more withdrawn, and brassy Charlotte more whiny. Charlotte discovers Humbert's diary entries detailing his passion for Lolita and characterizing her as "the Haze woman, the cow, the obnoxious mama, the brainless baba". She has an hysterical outburst, runs outside, and is hit by a car, dying on impact.

Humbert drives to Camp Climax to pick up Lolita, who doesn't yet know her mother is dead. They stay the night in a hotel that is handling an overflow influx of police officers attending a convention. One of the guests, a pushy, abrasive stranger, insinuates himself upon Humbert and keeps steering the conversation to his "beautiful little daughter," who is asleep upstairs. The stranger implies that he too is a policeman and repeats, too often, that he thinks Humbert is "normal." Humbert escapes the man's advances, and, the next morning, Humbert and Lolita enter into a sexual relationship. The two commence an odyssey across the United States, traveling from hotel to motel. In public, they act as father and daughter. After several days, Humbert tells Lolita that her mother is not sick in a hospital, as he had previously told her, but dead. Grief-stricken, she stays with Humbert.

In the fall, Humbert reports to his position at Beardsley College, and enrolls Lolita in high school there. Before long, people begin to wonder about the relationship between father and his over-protected daughter. Humbert worries about her involvement with the school play and with male classmates. One night he returns home to find Dr. Zempf, a pushy, abrasive stranger, sitting in his darkened living room. Zempf, speaking with a thick German accent, claims to be from Lolita's school and wants to discuss her knowledge of "the facts of life." He convinces Humbert to allow Lolita to participate in the school play, for which she had been selected to play the leading role.

While attending a performance of the play, Humbert learns that Lolita has been lying about how she was spending her Saturday afternoons when she claimed to be at piano practice. They get into a row and Humbert decides to leave Beardsley College and take Lolita on the road again. Lolita objects at first but then suddenly changes her mind and seems very enthusiastic. Once on the road, Humbert soon realizes they are being followed by a mysterious car that never drops away but never quite catches up. When Lolita becomes sick, he takes her to the hospital. However, when he returns to pick her up, she is gone. The nurse there tells him she left with another man claiming to be her uncle and Humbert, devastated, is left without a single clue as to her disappearance or whereabouts.

Some years later, Humbert receives a letter from Mrs. Richard T. Schiller, Lolita's married name. She writes that she is now married to a man named Dick, and that she is pregnant and in desperate need of money. Humbert travels to their home and finds that she is now a roundly expectant woman in glasses leading a pleasant, humdrum life. Humbert demands that she tell him who kidnapped her three years earlier. She tells him it was Clare Quilty, the man that was following them, who is a famous playwright and with whom her mother had a fling in Ramsdale days. She states Quilty is also the one who disguised himself as Dr. Zempf, the pushy stranger who kept crossing their path. Lolita herself carried on an affair with him and left with him when he promised her glamour. However, he then demanded she join his depraved lifestyle, including acting in his "art" films, which she vehemently refused.

Humbert begs Lolita to leave her husband and come away with him, but she declines. Humbert gives Lolita $13,000, explaining it as her money from the sale of her mother's house, and leaves to shoot Quilty in his mansion, where the film began. The epilogue explains that Humbert died of coronary thrombosis awaiting trial for Quilty's murder.

Cast

|

|

Cast notes

- Ed Bishop had his first film role in Lolita,[4] an uncredited appearance as the ambulance attendant who tells Humbert that Charlotte is dead. Bishop also played the shuttle pilot in 2001: A Space Odyssey, making him one of the few actors to appear in two Kubrick films.

Production

Direction

With Nabokov's consent, Kubrick changed the order in which events unfolded by moving what was the novel's ending to the start of the film, a literary device known as in medias res. Kubrick determined that while this sacrificed a great ending, it helped maintain interest, as he believed that interest in the novel sagged halfway through once Humbert was successful in seducing Lolita.[5]

The second half contains an odyssey across the United States and though the novel was set in the 1940s, Kubrick gave it a contemporary setting, shooting many of the exterior scenes in England with some back-projected scenery shot in the United States, including upstate eastern New York, along NY 9N in the eastern Adirondacks and a hilltop view of Albany from Rensselaer, on the east bank of the Hudson. Some of the minor parts were played by Canadian and American actors, such as Cec Linder, Lois Maxwell, Jerry Stovin and Diana Decker, who were based in England at the time. Kubrick had to film in England, as much of the money to finance the movie was not only raised there but also had to be spent there.[5] In addition, Kubrick was living in England at the time, and suffered from a deathly fear of flying.[6] Hilfield Castle featured in the film as Quilty's "Pavor Manor".

Casting

Mason was the first choice of Kubrick and producer Harris for the role of Humbert Humbert, but he initially declined due to a Broadway engagement while recommending his daughter, Portland, for the role of Lolita.[7] Laurence Olivier then refused the part, apparently on the advice of his agents. Kubrick considered Peter Ustinov but decided against him. Harris then suggested David Niven; Niven accepted the part but then withdrew for fear the sponsors of his TV show, Four Star Playhouse (1952), would object. Mason then withdrew from his play and got the part.

The role of Clare Quilty was greatly expanded from that in the novel and Kubrick allowed Sellers to adopt a variety of disguises throughout the film. Early on in the film, Quilty appears as himself: a conceited, avant-garde playwright with a superior manner. Later he is an inquisitive policeman on the porch of the hotel, where Humbert and Lolita are staying. Next he is the intrusive Beardsley High School psychologist, Doctor Zempf, who lurks in Humbert's front room, to persuade him to give Lolita more freedom in her after-school activities.[8] He is then seen as a photographer backstage at Lolita's play. Later in the film, he is an anonymous phone caller conducting a survey.

Jill Haworth was asked to take the role but she was under contract to Otto Preminger and he said "no."[9] Although Vladimir Nabokov originally thought that Sue Lyon was the right selection to play Lolita, years later Nabokov said that the ideal Lolita would have been Catherine Demongeot, a French actress who had played Zazie in Zazie in the Metro (1960), followed by only a few more films.[10]

Censorship

At the time the film was released, the ratings system was not in effect and the Hays Code, dating back to the 1930s, governed movie production. The censorship of the time inhibited Kubrick's direction; Kubrick later commented that, "because of all the pressure over the Production Code and the Catholic Legion of Decency at the time, I believe I didn't sufficiently dramatize the erotic aspect of Humbert's relationship with Lolita. If I could do the film over again, I would have stressed the erotic component of their relationship with the same weight Nabokov did."[5] Kubrick hinted at the nature of their relationship indirectly, through double entendre and visual cues such as Humbert painting Lolita's toes. In a 1972 Newsweek interview (after the ratings system had been introduced in late 1968), Kubrick said that he "probably wouldn't have made the film" had he realized in advance how difficult the censorship problems would be.[11]

The film is deliberately vague over Lolita's age. Kubrick commented, "I think that some people had the mental picture of a nine-year-old, but Lolita was twelve and a half in the book; Sue Lyon was thirteen." Actually, Lyon was 14 by the time filming started and 15 when it finished.[12] Although passed without cuts, Lolita was rated "X" by the British Board of Film Censors when released in 1962, meaning no one under 16 years of age was permitted to watch.[13]

Writing and narration

Humbert uses the term "nymphet" to describe Lolita, which he explains and uses in the novel; it appears twice in the movie and its meaning is left undefined.[14] In a voice-over on the morning after the Ramsdale High School dance, Humbert confides in his diary, "What drives me insane is the twofold nature of this nymphet, of every nymphet perhaps, this mixture in my Lolita of tender, dreamy childishness and a kind of eerie vulgarity. I know it is madness to keep this journal, but it gives me a strange thrill to do so. And only a loving wife could decipher my microscopic script."

This voice-over is a part of Humbert's narration, which is central to the novel. Kubrick uses it sparingly and apart from the above comment, only to set the scene for the film's next act. Humbert's comments are generally simple statements of fact, spiced with the odd personal reflection.

The only other one of these reflections which makes reference to Humbert's feelings towards Lolita is made after their move from Ramsdale to Beardsley. Here Humbert's comment seems to show only an interest in her education and cultural development: "Six months have passed and Lolita is attending an excellent school where it is my hope that she will be persuaded to read other things than comic books and movie romances."

The narration begins after the opening scenes but ceases once the odyssey begins. Kubrick makes no attempt to explain Humbert's fascination with Lolita, which a full narration would have done but merely treats it as a matter of fact.

Screenplay

The screenplay is credited to Nabokov, although very little of what he provided (later published in a shortened version) was used. Nabokov, following the success of the novel, moved out to Hollywood and penned a script for a film adaptation between March and September 1960. The first draft was extremely long—over 400 pages, to which producer Harris remarked "You couldn't make it. You couldn't lift it".[15] Nabokov remained polite about the film in public but in a 1962 interview before seeing the film, commented that it may turn out to be "the swerves of a scenic drive as perceived by the horizontal passenger of an ambulance".[16] Kubrick and Harris rewrote the script themselves, writing carefully to satisfy the needs of the censor.

Music

The music for the film was composed by Nelson Riddle (the main theme was by Bob Harris). The recurring dance number first heard on the radio when Humbert meets Lolita in the garden later became a hit single under the name "Lolita Ya Ya" with Sue Lyon credited with the singing on the single version.[17] The flip side was a 60s-style light rock song called "Turn off the Moon" also sung by Sue Lyon. "Lolita Ya Ya" was later recorded by other bands; it was also a hit single for The Ventures, reaching 61 on Billboard and then being included on many of their compilation albums.[18][19] In his biography of The Ventures, Del Halterman quotes an unnamed reviewer of the CD re-release of the original Lolita soundtrack as saying "The highlight is the most frivolous track, 'Lolita Ya Ya', a maddeningly vapid and catchy instrumental with nonsense vocals that comes across as a simultaneously vicious and good-humored parody of the kitschiest elements of early-sixties rock and roll."

Differences between the film and the book

There are many differences between Kubrick's film adaptation and Nabokov's novel, including some events that were entirely omitted. Most of the sexually explicit innuendos, references and episodes in the book were taken out of the film because of the strict censorship of the 1960s; the sexual relationship between Lolita and Humbert is implied and never depicted graphically on the screen. In addition, some events in the film differ from the novel, and there are also changes in Lolita's character. Some of the differences are listed below:

Lolita's age, name, feelings and fate

Lolita's age was raised from 12 to early teens in the film to meet MPAA standards. Kubrick had been warned that censors felt strongly about using a more physically developed actress, who would be seen to be at least 14. As such, Sue Lyon was chosen for the title role, partly due to her more mature appearance.

The name "Lolita" is used only by Humbert as a private pet nickname in the novel, whereas in the film several of the characters refer to her by that name. In the book, she is referred to simply as "Lo" or "Lola" or "Dolly" by the other characters. Various critics, such as Susan Sweeney, have observed that since she never calls herself "Lolita", Humbert's pet name denies her subjectivity.[20] Generally, the novel gives little information about her feelings.

The film is not especially focused on Lolita's feelings. In the medium of film, her character is inevitably fleshed out somewhat from the cipher that she remains in the novel. Nonetheless, Kubrick actually omits the few vignettes in the novel in which Humbert's solipsistic bubble is burst and one catches glimpses of Lolita's personal misery. Susan Bordo writes, "Kubrick chose not to include any of the vignettes from the novel which bring Lolita's misery to the forefront, nudging Humbert's obsession temporarily off center-stage. ...Nabokov's wife, Vera, insisted—rightly—on 'the pathos of Lolita's utter loneliness.'... In Kubrick's film, one good sobfest and dead mommy is forgotten. Humbert, to calm her down, has promised her a brand-new hi-fi and all the latest records. The same scene in the novel ends with Lolita sobbing, despite Humbert having plied her with gifts all day."[21] Bordo goes on to say "Emphasizing Lolita's sadness and loss would not have jibed of course with the film's dedication to inflecting the 'dark' with the comic; it would have altered the overwhelmingly ironic, anti-sentimental character of the movie." When the novel briefly gives us evidence of Lolita's sadness and misery, Humbert glosses over it but the film omits nearly all of these episodes.

Professor Humbert

Critic Greg Jenkins believes that Humbert is imbued with a fundamental likability in this film that he does not necessarily have in the novel.[22] He has a debonair quality in the film, while in the novel he can be perceived as much more repulsive. Humbert's two mental breakdowns leading to sanatorium stays before meeting Lolita are entirely omitted in the film, as are his earlier unsuccessful relationships with women his own age (whom he refers to in the novel as "terrestrial women") through which he tried to stabilize himself. His lifelong complexes around young girls are largely concealed in the film, and Lolita appears older than her novelistic counterpart, both leading Jenkins to comment "A story originally told from the edge of a moral abyss is fast moving toward safer ground."[23] In short, the novel early flags Humbert as both mentally unsound and obsessively infatuated with young girls in a way the film never does.

Jenkins notes that Humbert even seems a bit more dignified and restrained than other residents of Ramsdale, particularly Lolita's aggressive mother, in a way that invites the audience to sympathize with Humbert. Humbert is portrayed as someone urbane and sophisticated trapped in a provincial small town populated by slightly lecherous people, a refugee from Old World Europe in an especially crass part of the New World. For example, Lolita's piano teacher comes across in the film as aggressive and predatory compared to which Humbert seems fairly restrained.[24] The film character of John Farlow talks suggestively of "swapping partners" at a dance in a way that repels Humbert. Jenkins believes that in the film it is Quilty, not Humbert, who acts as the embodiment of evil.[25] The expansion of Quilty's character and the way Quilty torments Humbert also invites the audience to sympathize with Humbert.

Because Humbert narrates the novel, his increased mental deterioration due to anxiety in the entire second half of the story is more obvious from the increasingly desperate tone of his narrative. While the film shows Humbert's increasingly severe attempts to control Lolita, the novel shows more of Humbert's loss of self-control and stability.

Jenkins also notes that some of Humbert's more brutal actions are omitted or changed from the film. For example, in the novel he threatens to send Lolita to a reformatory, while in the film he promises to never send her there.[26] He also notes that Humbert's narrative style in the novel, although elegant, is wordy, rambling, and roundabout, whereas in the film it is "subdued and measured".[24]

Humbert's infatuation with "nymphets" in the novel

The film entirely omits the critical episode in Humbert's life in which at age 14 he was interrupted making love to young Annabel Leigh who shortly thereafter died, and consequently omits all indications that Humbert had a preoccupation with prepubescent girls prior to meeting Dolores Haze. In the novel, Humbert gives his youthful amorous relationship with Annabel Leigh, thwarted by both adult intervention and her death, as the key to his obsession with nymphets. The film's only mention of "nymphets" is an entry in Humbert's diary specifically revolving around Lolita.

Humbert explains that the smell and taste of youth filled his desires throughout adulthood: "that little girl with her seaside limbs and ardent tongue haunted [him] ever since".[27] He thus claims that "Lolita began with Annabel"[28] and that Annabel's spell was broken by "incarnating her in another".[27]

The idea that anything connected with young girls motivated Humbert to accept the job as professor of French Literature at Beardsley College and move to Ramsdale at all is entirely omitted from the film. In the novel he first finds accommodations with the McCoo family. He accepts the professorship because the McCoos have a twelve-year-old daughter, a potential "enigmatic nymphet whom [he] would coach in French and fondle in Humbertish."[29] However, the McCoo house happens to burn down in the few days prior to his arrival, and this is when Mrs. Haze offers to accommodate Humbert.

Humbert's attitudes to Charlotte

Susan Bordo has noticed that in order to show the callous and cruel side of Humbert's personality early in the film, Nabokov and Kubrick have shown additional ways in which Humbert behaves monstrously towards her mother, Charlotte Haze. He mocks her declaration of love towards him, and takes a pleasant bath after her accidental death. This effectively replaces the voice-overs in which he discusses his plans to seduce and molest Lolita as a means of establishing Humbert as manipulative, scheming, and selfish.[30] However, Greg Jenkins has noted that Humbert's response to Charlotte's love note in the film is still much kinder than that in the novel, and that the film goes to significant lengths to make Charlotte unlikable.

Expansion of Clare Quilty

Quilty's role is greatly magnified in the film and brought into the foreground of the narrative. In the novel Humbert catches only brief uncomprehending glimpses of his nemesis before their final confrontation at Quilty's home, and the reader finds out about Quilty late in the narrative along with Humbert. Quilty's role in the story is made fully explicit from the beginning of the film, rather than being a concealed surprise twist near the end of the tale. In a 1962 interview with Terry Southern, Kubrick describes his decision to expand Quilty's role, saying "just beneath the surface of the story was this strong secondary narrative thread possible—because after Humbert seduces her in the motel, or rather after she seduces him, the big question has been answered—so it was good to have this narrative of mystery continuing after the seduction."[31] This magnifies the book's theme of Quilty as a dark double of Humbert, mirroring all of Humbert's worst qualities, a theme which preoccupied Kubrick.[32]

The film opens with a scene near the end of the story, Humbert's murder of Quilty. This means that the film shows Humbert as a murderer before showing us Humbert as a seducer of minors, and the film sets up the viewer to frame the following flashback as an explanation for the murder. The film then goes back to Humbert's first meeting with Charlotte Haze and continues chronologically until the final murder scene is presented once again. The book, narrated by Humbert, presents events in chronological order from the very beginning, opening with Humbert's life as a child. While Humbert hints throughout the novel that he has committed murder, its actual circumstances are not described until near the very end. NPR's Bret Anthony Johnston notes that the novel is sort of an inverted murder mystery: you know someone has been killed, but you have to wait to find out who the victim is.[33] Similarly, the online Doubleday publisher's reading guide to Lolita notes "the mystery of Quilty's identity turns this novel into a kind of detective story (in which the protagonist is both detective and criminal)."[34] This effect is, of course, lost in the Kubrick film.

In the novel, Miss Pratt, the school principal at Beardsley, discusses with Humbert Dolores's behavioral issues and among other things persuades Humbert to allow her to participate in the dramatics group, especially one upcoming play. In the film, this role is replaced by Quilty disguised as a school psychologist named "Dr. Zempf". This disguise does not appear in the novel at all. In both versions, a claim is made that Lolita appears to be "sexually repressed", as she mysteriously has no interest in boys. Both Dr. Zempf and Miss Pratt express the opinion that this aspect of her youth should be developed and stimulated by dating and participating in the school's social activities. While Pratt mostly wants Humbert to let Dolores generally into the dramatic group, Quilty (as Zempf) is specifically focused on the high school play (written by Quilty and produced with some supervision from him) which Lolita had secretly rehearsed for (in both the film and novel). In the novel Miss Pratt naïvely believes this talk about Dolores' "sexual repression", while Quilty in his disguise knows the truth. Although Peter Sellers is playing only one character in this film, Quilty's disguise as Dr. Zempf allows him to employ a mock German accent that is quintessentially in the style of Sellers's acting.[35]

With regard to this scene, playwright Edward Albee's 1981 stage adaptation of the novel follows Kubrick's film rather than the novel.

The movie retains the novel's theme of Quilty (anonymously) goading Humbert's conscience on many occasions, though the details of how this theme is played out are quite different in the film. He has been described as "an emanation of Humbert's guilty conscience",[36] and Humbert describes Quilty in the novel as his "shadow".[37]

The first and last word of the novel is "Lolita".[38] As film critic Greg Jenkins has noted, in contrast to the novel, the first and last word of the screenplay is "Quilty".[39]

Contemplating murder of Charlotte Haze

- In the novel, Humbert and Charlotte go swimming in Hourglass Lake, where Charlotte announces she will ship Lo off to a good boarding school; that part takes place in bed in the film. Humbert's contemplation of possibly killing Charlotte similarly takes place at Hourglass Lake in the book, but at home in the film. This difference affects Humbert's contemplated method of killing Charlotte. In the book he is tempted to drown her in the lake, whereas in the film he considers the possibility of shooting her with a pistol whilst in the house, in both scenarios concluding that he could never bring himself to do it. In his biography of Kubrick, Vincent LoBrutto notes that Kubrick tried to recreate Hourglass Lake in a studio, but became uncomfortable shooting such a pivotally important exterior scene in the studio, so he refashioned the scene to take place at home.[40] Susan Bordo notes that after Charlotte's actual death in the film, two neighbors see Humbert's gun and falsely conclude Humbert is contemplating suicide, while in fact he had been contemplating killing Charlotte with it.[41]

- The same attempted killing of Charlotte appears in the "Deleted Scenes" section of the DVD of the 1997 film (now put back at Hourglass Lake). In the novel Humbert really considers killing Charlotte and later Lolita accuses Humbert of having deliberately killed her. Only the first scene is in the 1962 film and only the latter scene appears in the 1997 film.

Lolita's friends at school

- Lolita's friend, Mona Dahl, is a friend in Ramsdale (the first half of the story) in the film and disappears quite early in the story. In the film, Mona is simply the host of a party which Lolita abandons early in the story. Mona is a friend of Lolita's in Beardsley (the second half of the story) in the novel. In the novel Mona is active in the school play, Lolita tells Humbert stories about Mona's love life, and Humbert notes Mona had "long since ceased" to be (if ever she was) a "nymphet". Mona has already had an affair with a Marine and appears to be flirting with Humbert. She keeps Lolita's secrets and helps Lolita lie to Humbert when Humbert discovers that Lolita has been missing her piano lessons. In the film, Mona in the second half seems to have been replaced by a "Michele" who is also in the play and having an affair with a Marine and backs up Lolita's fibs to Humbert. Film critic Greg Jenkins claims that Mona has simply been entirely eliminated from the film.[42]

- Humbert is suspicious that Lolita is developing an interest in boys at various times throughout the story. He suspects no one in particular in the novel. In the film, he is twice suspicious of a pair of boys, Rex and Roy, who hang out with Lolita and her friend Michele. In the novel, Mona has a friend named Roy.

Other differences

- In the novel, the first mutual attraction between Humbert and Lolita begins because Humbert resembles a celebrity she likes. In the film, it occurs at a drive-in horror film when she grabs his hand. The scene is from Christopher Lee's The Curse of Frankenstein when the monster removes his mask. Christine Lee Gengaro proposes that this suggests that Humbert is a monster in a mask,[43] and the same theory is developed at greater length by Jason Lee.[44] As in the novel, Lolita shows affection for Humbert before she departs for summer camp.

- In the novel, both the hotel at which Humbert and Dolores first have relations and the stage-play by Quilty for which Dolores prepares to perform in at her high school is called The Enchanted Hunter. However, in the novel school headmistress Pratt erroneously refers to the play as The Hunted Enchanter. In Kubrick's film, the hotel bears the same name as in the novel, but now the play really is called The Hunted Enchanter. Both names are established only through signage – the banner for the police convention at the hotel and the marquee for the play – the names are never mentioned in dialogue.

- The relationships between Humbert and other women before and after Lolita is omitted from the film. Greg Jenkins sees this as part of Kubrick's general tendency to simplify his narratives, also noting that the novel therefore gives us a more "seasoned" view of Humbert's taste in women.[45]

- Only the film has a police convention at the hotel where Humbert allows Lolita to seduce him. Kubrick scholar Michel Ciment sees this as typical of Kubrick's general tendency to assail authority figures.[46]

- Lolita completes the school play (written by Clare Quilty) in the film, but drops out prior to finishing it in the novel. In the film, we see that Quilty's play has suggestive symbolism, and Humbert's confrontation with Lolita over her missing her piano lessons occurs after her triumphal debut in the play's premiere.[47]

Quilty's "Dr. Zempf" and Peter Sellers role as Doctor Strangelove

The film has a scene lasting six minutes in which Quilty disguises himself as a German-accented high school psychologist named Dr. Zempf who persuades Humbert to allow Lolita more personal freedom so that she can act in the high school play (which is written by Quilty and produced with some supervision from him). This is modified from a scene in the novel in which there is a similar conversation with a genuine female school psychologist. The film version of this scene was sufficiently memorable that Edward Albee incorporated it into his stage adaptation of Lolita.

Numerous observers have seen similarities between Peter Sellers' performance of Quilty-as-Zempf and his subsequent role in Stanley Kubrick's next film as Doctor Strangelove. Stanley Kubrick himself in an interview with Michel Ciment described both characters as "parodies of movie clichés of Nazis".[48] Commenting elsewhere on the characters, Ciment writes "Peter Sellers prefigured his creation of Dr Strangelove, particularly in the role of Dr Zempf, the school psychologist whose thick German accent recalls that of the mad professor (note Kubrick's ambiguous feelings towards Germany, his admiration for its culture... his fear of its demonstrations of power...)".[49] Thomas Allen Nelson has said that in this part of his performance, "Sellers twists his conception of Quilty toward that neo-Nazi monster, who will roll out of the cavernous shadows of Dr. Strangelove",[50] later noting that Zempf "exaggerates Humbert's European pomposity through his psychobabble and German anality." The Kubrick interview has been commented by Geoffrey Cocks, author of a controversial book on the impact of the Holocaust on Kubrick's overall work, who notes that "Dr. Strangelove himself... is the mechanical chimera of modern horror."[51]

Other observers of this similarity include Internet film critic Tim Dirks who has also noted that Sellers's smooth German-like accent and the chair-bound pose in this scene are similar to that of Dr. Strangelove.[52] Finally, Barbara Wyllie, writing in Julian Connelly's anthology The Cambridge Companion to Nabokov, speaks of "Quilty's visit to the house in Beardsley, masquerading as Dr. Zempf, a German psychologist (a Sellers character that prefigures Dr. Strangelove in Kubrick's film of 1964)."[53]

Reception

Lolita premiered on June 13, 1962 in New York City. It performed fairly well, with little advertising relying mostly on word-of-mouth; many critics seemed uninterested or dismissive of the film while others gave it glowing reviews. However, the film was very controversial, due to the hebephilia-related content,[54][55] and therefore while many things are suggested, hardly any are shown. The film has been re-appraised by critics over time, and currently has a score of 95% on Rotten Tomatoes.[56]

The film was a commercial success. Produced on budget of $2 million, Lolita grossed $9,250,000 domestically.[2] During its initial run, the movie earned an estimated $4.5 million in North American rentals.[57]

Years after the film's release it has been released on VHS, Laserdisc, DVD, and Blu-ray. It earned $3.7 million in rentals in the USA on VHS.

Awards and honors

The film was nominated for a number of awards, including an Academy Award for Best Adapted Screenplay, and won a Golden Globe for Most Promising Newcomer which went to Sue Lyon.

Wins

Nominations

- Academy Award for Best Adapted Screenplay – Vladimir Nabokov

- British Academy of Film and Television Arts Award for Best Actor – James Mason

- Outstanding Directorial Achievement in Motion Pictures – Stanley Kubrick

- Golden Globe Award for Best Motion Picture Actor – James Mason

- Golden Globe Award for Best Motion Picture Actress – Shelley Winters

- Golden Globe Award Best Motion Picture Director – Stanley Kubrick

- Golden Globe Award for Best Supporting Actor – Peter Sellers

- Venice Film Festival Award for Best Director – Stanley Kubrick

Alternate versions

- The scene where Lolita first "seduces" Humbert as he lies on the cot is approximately 10 seconds longer in the British and Australian cut of the film. In the U.S. edition, the shot fades as she whispers the details of the "game" she played with Charlie at camp. In the UK/Australian print, the shot continues as Humbert mumbles that he's not familiar with the game. She then bends down again to whisper more details. Kubrick then cuts to a closer shot of Lolita's face as she says "Well, alrighty then" and then fades as she begins to descend onto Humbert on the cot. The latter cut of the film was used for the Region 1 DVD release. It is also the version aired on Turner Classic Movies in the U.S.

- The Criterion LaserDisc release is the only one to use a transfer approved by Stanley Kubrick. This transfer alternates between a 1.33 and a 1.66 aspect ratio (as does the Kubrick-approved Strangelove transfer). All subsequent releases to date have been 1.66 (which means that all the 1.33 shots are slightly matted).

Other film adaptations

Lolita was filmed again in 1997, directed by Adrian Lyne, starring Jeremy Irons as Humbert, Melanie Griffith as Charlotte and Dominique Swain as Lolita. The film was widely publicized as being more faithful to Nabokov than the Kubrick film. Although many observed this was the case (such as Erica Jong writing in The New York Observer),[58] the film was not as well received as Kubrick's version, and was a major box office bomb, first shown on the Showtime cable network, then released theatrically, grossing only $1 million at the US box office based on a $62 million budget.

See also

References

- ↑ "Company Information". movies.nytimes.com. Retrieved October 3, 2010.

- 1 2 Box Office Information for Lolita. The Numbers. Retrieved June 13, 2013.

- ↑ "Lolita". AllMovie.

- ↑ "Ed Bishop". IMDb.

- 1 2 3 "An Interview with Stanley Kubrick (1969)" by Joseph Gelmis. Excerpted from The Film Director as Superstar (Garden City, N.Y.: Doubleday, 1970).

- ↑ Rose, Lloyd. "Stanley Kubrick, at a Distance" Washington Post (June 28, 1987)

- ↑ "Portland Mason". Retrieved March 5, 2015.

- ↑ Kubrick in Nabokovland by Thomas Allen Nelson. Excerpted from Kubrick: Inside a Film Artist's Maze (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2000, pp 60–81)

- ↑ Lisanti, Tom (2001), Fantasy Femmes of Sixties Cinema: Interviews with 20 Actresses from Biker, Beach, and Elvis Movies, McFarland, p. 71, ISBN 978-0-7864-0868-9

- ↑ Boyd, Brian (1991). Vladimir Nabokov: the American years. Princeton NJ: Princeton University Press. p. 415. ISBN 9780691024714. Retrieved 30 August 2013.

- ↑ "'Lolita': Complex, often tricky and 'a hard sell'". Archived from the original on January 3, 2005. Retrieved March 6, 2015.

- ↑ Graham Vickers (1 August 2008). Chasing Lolita: How Popular Culture Corrupted Nabokov's Little Girl All Over Again. Chicago Review Press. pp. 127–. ISBN 978-1-55652-968-9.

- ↑ "Lolita (1962) at Rotten Tomatoes". Rotten Tomatoes. Rotten Tomatoes. Retrieved November 1, 2011.

- ↑ "Lolita (1962)" A Review by Tim Dirks—A comprehensive review containing extensive dialogue quotes. These quotes include other details of Humbert's narration.

- ↑ Duncan 2003, p. 73.

- ↑ Nabokov, Strong Opinions, Vintage International Edition, pp. 6–7

- ↑ Tony Maygarden. "SOUNDTRACKS TO THE FILMS OF STANLEY KUBRICK". The Endless Groove. Retrieved December 7, 2010.

- ↑ "The Ventures :: Discography Charts". theventures.com.

- ↑ Halterman, Del (2009). Walk-Don't Run—The Story of the Ventures. Lulu.com. p. 80.

- ↑ See footnote 6.

- ↑ The male body: a new look at men in public and in private by Susan Bordo p. 305

- ↑ Jenkins pp. 34–64

- ↑ Jenkins, p. 40

- 1 2 Jenkins p. 58

- ↑ Jenkins p. 42

- ↑ Jenkins, p. 54

- 1 2 Annotated Lolita p. 15

- ↑ Annotated Lolita p. 14

- ↑ Annotated Lolita p. 35

- ↑ Bordo, Susan (2000). The male body: a new look at men in public and in private. Macmillan. p. 303. ISBN 0-374-52732-6.

- ↑ "Terry Southern's Interview with Kubrick, 1962". terrysouthern.com.

- ↑ Michel Ciment Kubrick': The Definitive Edition p. 92

- ↑ "Why 'Lolita' Remains Shocking, And A Favorite". NPR.org. July 7, 2006.

- ↑ "Lolita - Knopf Doubleday". Knopf Doubleday.

- ↑ An interesting discussion of this scene is in Stanley Kubrick and the Art of Adaptation: Three Novels, Three Films by Greg Jenkins pp. 56–57

- ↑ Justin Wintle in The concise new makers of modern culture p. 556

- ↑ Annotated Lolita p. lxi

- ↑ This is discussed in a footnote in Annotated Lolita p. 328

- ↑ Stanley Kubrick and the Art of Adaptation: Three Novels, Three Films by Greg Jenkins p. 67

- ↑ LoBrutto, Vincent (1999). Stanley Kubrick: A Biography. Da Capo Press. p. 208. ISBN 0-306-80906-0.

- ↑ Bordo, Susan (2000). The male body: a new look at men in public and in private. Macmillan. p. 304. ISBN 0-374-52732-6.

- ↑ Jenkins, Greg (1997). Stanley Kubrick and the art of adaptation: three novels, three films. McFarland. p. 151. ISBN 0-7864-0281-4.

- ↑ Gengaro, Christine Lee (2012). Listening to Stanley Kubrick: The Music in His Films. Rowman & Littlefield,. p. 52. ISBN 0571211089.

- ↑ Lee, Jason (2009). Celebrity, Pedophilia, and Ideology in American Culture. Cambria Press,. pp. 109–111. ISBN 1604975997.

- ↑ Jenkins, Greg (2003). Stanley Kubrick and the Art of Adaptation: Three Novels, Three Films. McFarland. p. 156. ISBN 0786430974.

- ↑ Ciment, Michel (2003). Kubrick: The Definitive Edition,. Macmillan. p. 92. ISBN 0571211089.

- ↑ Jenkins, Greg (2003). Stanley Kubrick and the Art of Adaptation: Three Novels, Three Films. McFarland. p. 57. ISBN 0786430974.

- ↑ Ciment, Michel; Gilbert Adair; Robert Bononno (2003). Kubrick: The Definitive Edition. Macmillan. p. 156. ISBN 0-571-21108-9.

- ↑ Ciment, Michel; Gilbert Adair; Robert Bononno (2003). Kubrick: The Definitive Edition. Macmillan. p. 92. ISBN 0-571-21108-9.

- ↑ Nelson, Thomas Allen (2000). Kubrick, inside a film artist's maze. Indiana University Press. p. 80. ISBN 0-253-21390-8.

- ↑ Cocks, Geoffrey (2004). The wolf at the door: Stanley Kubrick, history, & the Holocaust. Peter Lang. p. 114. ISBN 0-8204-7115-1.

- ↑ "Lolita (1962)" A Review by Tim Dirks.

- ↑ Connelly, Julian (2005). The Cambridge Companion to Nabokov (Cambridge Companions to Literature). Cambridge University Press. p. 212. ISBN 978-0-521-82957-1.

- ↑ PAI RAIKAR, RAMNATH N (August 8, 2015). "Lolita: The girl who knew too much". Navhind Times. Retrieved 29 November 2016.

- ↑ "Lolita (película de 1997)" (in Spanish). Helpes.eu. Retrieved 29 November 2016.

- ↑ Lolita at Rotten Tomatoes

- ↑ "All-Time Top Grossers". Variety. January 8, 1964. p. 69.

- ↑ "Erica Jong Screens Lolita With Adrian Lyne". The New York Observer. May 31, 1998. Retrieved 2009-05-11.

- Bibliography

- Richard Corliss, Lolita London: British Film Institute, 1994; ISBN 0-85170-368-2

- Hughes, David (2000). The Complete Kubrick. Virgin Publishing. ISBN 0-7535-0452-9.

- Jenkins, Greg (1997). Stanley Kubrick and the art of adaptation: three novels, three films. McFarland. ISBN 0-7864-0281-4. Pages 34–64 are focused on Lolita

External links

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Lolita (1962 film) |

- Lolita at the Internet Movie Database

- Lolita at the TCM Movie Database

- Lolita at the American Film Institute Catalog

- Lolita at Rotten Tomatoes