Otto Preminger

| Otto Preminger | |

|---|---|

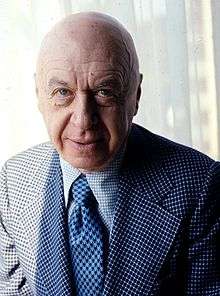

Preminger in 1976, by Allan Warren | |

| Born |

Otto Ludwig Preminger 5 December 1905 Wiznitz, Austria-Hungary (present Vyzhnytsia, Ukraine) |

| Died |

23 April 1986 (aged 80) New York City, New York, U.S. |

| Cause of death |

Lung cancer Alzheimer's disease |

| Occupation | Director, producer, actor |

| Years active | 1931–86 |

| Spouse(s) |

Marion Mill (m. 1932–49) (d.1972) Mary Gardner (m. 1951–59) (d.1998) Hope Bryce (m. 1971–86) |

Otto Ludwig Preminger (/ˈprɛməndʒɪr/,[1] German pronunciation: [ˈpreːmiŋɐ];[2] 5 December 1905 – 23 April 1986)[3] was an Austrian American theatre and film director. He is known for directing over 35 feature films in a five-decade career after leaving the theatre. He first gained attention for film noir mysteries such as Laura (1944) and Fallen Angel (1945), while in the 1950s and '60s, he directed a number of high-profile adaptations of popular novels and stage works. Several of these later films pushed the boundaries of censorship by dealing with topics which were then taboo in Hollywood, such as drug addiction (The Man with the Golden Arm, 1955), rape (Anatomy of a Murder, 1959) and homosexuality (Advise & Consent, 1962). He was twice nominated for the Academy Award for Best Director. He also had a few acting roles.

Early life

Preminger was born in 1905 in Wiznitz, Bukovina (east of Galicia), Austro-Hungarian Empire (now Vyzhnytsia, Ukraine), into a Jewish family. His parents were Josefa (née Fraenkel) and Markus Preminger[4][5] born in 1877 in Czernowitz (Czernovic), capital of Bukovina (now Chernivtsi, Ukraine, 70.7 kilometres (43.9 mi) east of Wiznitz). As an Attorney General of Austria-Hungary, Markus was a proud public prosecutor on the verge of an extraordinary career defending the interests of the Emperor Franz Josef. The couple provided a stable home life for Preminger and his younger brother Ingo Preminger, later the producer of the original film version of M*A*S*H (1970). Otto recalled:

My father believed that it was impossible to be too kind or too loving to a child. He never punished me. When there were problems he sat down and discussed them with me reasonably, as though I was an adult. I don't think my mother agreed completely with this method but she acted, as always, according to his wishes. I adored him. I had an affectionate relationship with my mother; she was a wonderful, warm-hearted woman, but she did not really play a large part in the formation of my character. Intellectually my father influenced me more than my mother.[6]

After the assassination in 1914 of Archduke Franz Ferdinand, the heir to the throne, which led to the Great War, Russia entered the war on the Serbian side. Like other refugees in flight, Markus Preminger saw Austria as a safe haven for his family. He was able to secure a job as a public prosecutor in Graz, capital of the Austrian province of Styria. Preminger prosecuted nationalist Serbs and Croats who had been imprisoned as suspected enemies of the Empire. When the Preminger family relocated, Otto was nearly nine, and was enrolled in a school where instruction in Catholic dogma was mandatory and Jewish history and religion had no place on the syllabus. Ingo, not yet four, remained at home.

After a year in Graz, the decisive public prosecutor was summoned to Vienna, where he was offered an eminent position, roughly equivalent to that of the United States Attorney General. Markus was told that the position would be his only if he converted to Catholicism. In a gesture of defiance and self-assertion, Markus refused but he received the position anyway. In 1915, Markus relocated his family to Vienna, the city that Otto later claimed to have been born in. Although now working for the emperor, Markus was a government official, respectable, but not part of the highly prized inner city. As a result, the family started their new lives with rather modest quarters. Vienna was still an imperial capital with an array of cultural offerings that tempted Otto. At ten, he was already incurably stagestruck.

Career

Theater

Preminger's first theatrical ambition was to become an actor. In his early teens, he was able to recite from memory many of the great monologues from the international classic repertory, and, never shy, he demanded an audience. Preminger's most successful performance in the National Library rotunda was Mark Antony's funeral oration from Julius Caesar. As he read, watched, and after a fashion began to produce plays, he began to miss more and more classes in school. Austria's failing fortunes during the war had no impact on the Premingers. Markus moved his family to a more fashionable district in 1916.

As the war came to an end, Markus formed his own law practice. Markus instilled in both his sons a sense of fair play as well as respect for those with opposing viewpoints. As his father's practice continued to thrive in postwar Vienna, Otto began seriously contemplating a career in the theater. In 1923, when Preminger was seventeen, his soon-to-be mentor, Max Reinhardt, the renowned Viennese-born director, announced plans to establish a theatrical company in Vienna. Reinhardt's announcement was seen as a call of destiny to Preminger. He began writing to Reinhardt weekly, requesting an audition. After a few months, Preminger, frustrated, gave up, and stopped his daily visit to the post office to check for a response. Unbeknownst to him, a letter was waiting with a date for an audition which Preminger had already missed by two days. Feigning illness, Preminger skipped classes and began to hover near the stage door hoping to encounter Reinhardt associate Dr. Stefan Hock, begging for another audition.

Preminger explained to his father that a career in theater was not just a ploy to excuse himself from school. This was a way of life, and it was the only one he wanted. In order to obtain his father's full blessing, Preminger finished school and completed the study of law at the University of Vienna. He juggled a commitment to the University and his new position as a Reinhardt apprentice. The two developed a mentor-and-protege relationship, becoming both a confidant and teacher. When the theater opened, on April 1, 1924, Preminger appeared as a furniture mover in Reinhardt's comedia staging of Carlo Goldoni's The Servant of Two Masters. His next, and more substantial appearance came late the following month with William Dieterle (who would also later move to Hollywood) in The Merchant of Venice. Other notable alumni with whom Preminger would work the same year were Mady Christians, who died of a stroke after having been blacklisted during the McCarthy era, and Nora Gregor, who was to star in Jean Renoir's La Règle du jeu (1939).

Reinhardt may have had reservations about Preminger's acting but he quickly detected the young man's abilities as an administrator. He appointed Preminger as an assistant in the Reinhardt acting school that opened in the theater at Schönbrunn, the former summer palace of the emperor. The following summer, a frustrated Preminger was no longer content to occupy the place of a subordinate and he decided to leave the Reinhardt fold. His status as a Reinhardt muse gave him an edge over much of his competition when it came to joining German-speaking theater. His first theater assignments as a director in Aussig were plays ranging from the sexually provocative Lulu plays, and from Berlin he imported Roar China!, a pro-Communist agitprop. Preminger displayed pleasure in discovering new talent, but also created pitfalls with his unruly temper and disdain for directorial collaborations.

In 1930, a wealthy industrialist from Graz approached the rising young theater director with an offer to direct a film called Die große Liebe (The Great Love). Preminger did not have the same passion for the medium as he had for theater. He accepted the assignment nonetheless. The film premiered at the Emperor Theater in Vienna on 21 December 1931, to strong reviews and business. From 1931-1935, Preminger directed twenty-six shows. Among the performers he hired were Lili Darvas, Lilia Skala, Harry Horner, Oskar Karlweis, Albert Bassermann, and Luise Rainer, who was to win back-to-back Academy Awards in 1936 and 1937.[7][8]

It was not until the spring of 1931 that Preminger's carefree bachelor lifestyle was threatened when he met a Hungarian woman named Marion Mill. The couple married soon afterwards in the summer of 1932 in a plain ceremony on the bride's birthday, August 3, only thirty minutes after her divorce from her first husband had been finalized. The couple moved into an apartment of their own. Preminger immediately informed his wife that she could not pursue a theatrical career.

Hollywood

In April 1935, as Preminger was rehearsing a boulevard farce, The King with an Umbrella, he received a summons from American film producer Joseph Schenck to a five o'clock meeting at the Imperial Hotel. Schenck and partner, Darryl F. Zanuck, co-founders of Twentieth Century-Fox, were on the lookout for new talent. Within a half-hour of meeting Schenck, Preminger accepted an invitation to work for Fox in Los Angeles.

Preminger's first assignment was to direct a vehicle for Lawrence Tibbett, whom Zanuck wanted to get rid of. Preminger worked efficiently, completing the film well within the budget and well before the scheduled shooting deadline. The film opened to tepid notices in November 1936. Zanuck promoted him to the A-list, assigning him a story called Nancy Steele Is Missing, which was to star Wallace Beery (who had won an Academy Award for The Champ a few years earlier.) Beery, however, refused to do the film, saying, "I won't do a picture with a director whose name I can't pronounce".

Zanuck instead gave Preminger the task of directing another B-picture screwball comedy film Danger – Love at Work. French starlet Simone Simon was cast in the lead but was later fired by Zanuck and replaced with Ann Sothern. The premise is that eight members of an eccentric, wealthy family have inherited their grandfather's land, and the protagonist, (played by Jack Haley) is a lawyer tasked with persuading the family to hand the land over to a corporation that believes there is oil on the property. One of the female members of the wealthy family provides the romantic interest. Reviews of the disposable farce, released in September 1937, were surprisingly pleasant.

In November 1937, Zanuck's perennial emissary Gregory Ratoff brought Preminger the news that Zanuck had chosen him to direct Kidnapped, which was to be the most expensive feature to date for Twentieth Century-Fox. Zanuck himself had adapted the Robert Louis Stevenson novel, set in the Scottish Highlands. After reading Zanuck's script, Preminger knew he was in trouble since he would be a foreign director directing in a foreign setting.

During the shooting of Kidnapped, while screening footage of the film with Zanuck, the studio head accused Preminger of making changes in a scene; in particular, one with child actor Freddie Bartholomew and a dog. Preminger, composed at first, explained, claiming he shot the scene exactly as written. Zanuck insisted that he knew his own script. The confrontation escalated and ended with Preminger exiting the office and slamming the door. Days later, the lock to Preminger's office was changed, and his name was removed from the door. After his parking space was relocated to a remote spot, Preminger stopped going into the studio. At that point, a representative of Zanuck offered Preminger a buyout deal which he rejected: Preminger wanted to be paid for the remaining eleven months of his two-year contract. He earched for work at other studios, but received no offers – only two years after his arrival in Hollywood, Preminger was unemployed in the movie industry.

He returned to New York, and began to focus on the stage again. Success came quickly on Broadway for Preminger, with long-running productions, including Outward Bound with Laurette Taylor and Vincent Price, My Dear Children with John and Elaine Barrymore and Margin for Error, in which Preminger played a shiny-domed villainous Nazi. Additionally, a week after the opening of Margin, Preminger was offered a teaching position at the Yale School of Drama, and began commuting twice a week to Connecticut to lecture on directing and acting.

Nunnally Johnson, a Hollywood writer, was impressed with Preminger's performance in Margin, and called to ask if he would be interested in playing another Nazi in a film called The Pied Piper. The film was to be made for Twentieth Century-Fox, the studio that had banished him, but as he was In need of money, Preminger accepted on the spot. Even in the absence of Zanuck, who had joined the Army after Pearl Harbor, Preminger did not expect to remain in Hollywood. After collecting a sizable salary for his work, he was preparing to return to New York when his agent informed him that Fox wanted him to reprise his role in a film adaptation of Margin for Error. Ernst Lubitsch was set to direct and Preminger was to appear onscreen with Joan Bennett and Milton Berle. Not long after production began, Lubitsch withdrew from the project, and Preminger saw his chance. Preminger persuaded William Goetz, who was running Fox in Zanuck's absence, to give him another opportunity to direct.

Goetz was soon impressed with his views of Preminger's dailies each night, and offered him a new seven-year contract calling on his services as both a director and actor. Preminger took full measure of the temporary studio czar, and accepted. He completed production on schedule, although with a slightly increased budget, by November 1942. Critics were dismissive upon the film's release the following February, noting the bad timing of the release, coinciding with the war. Before his next assignment with Fox, Preminger was asked by movie mogul Samuel Goldwyn to appear as a Nazi once more, this time in a Bob Hope comedy called They Got Me Covered.

Preminger hoped to find possible properties he could develop before Zanuck's return, one of which was Vera Caspary's suspense novel Laura. Before production would begin on Laura, Preminger was given the green light to produce and direct Army Wives, another B-picture morale booster for a country at war. Its focus was on showing the sacrifices made by women as they send their husbands off to the front. Cast in the lead was Jeanne Crain, a contract player with Fox who was being groomed for stardom. Eugene Pallette played Crain's father. Preminger clashed with Pallette, claiming he was "an admirer of Hitler and [he was] convinced that Germany would win the war."[9] Pallette reportedly refused to sit down at the same table with a black actor in a scene set in a kitchen.[10]

Preminger furiously informed Zanuck, who had returned to Hollywood, who fired Pallette, whose scenes had already been shot. Army Wives was given the new title, In the Meantime, Darling and opened in September 1944, with an estimated budget of $450,000. Aside from the incident with Pallette, no other complications arose during the filming; the hurdles would instead come during the shooting of Laura.

Laura

Zanuck returned from the armed services with his grudge against Preminger intact. Preminger was not granted permission to direct Laura only to serve as producer. Rouben Mamoulian was chosen to direct. Mamoulian began ignoring his producer and even started to rewrite the script. Although Preminger had no complaints about the casting of the relatively unknown Gene Tierney and Dana Andrews, he balked at their choice for Waldo: Laird Cregar. Preminger explained to Zanuck that audiences would immediately identify Cregar as a villain, especially after Cregar's role as Jack the Ripper in The Lodger. Preminger wanted stage actor Clifton Webb to play Waldo and persuaded his boss to give Webb a screen test. The persuasion paid off and Webb was cast (and earned a long-term Fox contract) and Mamoulian was fired for creative differences.

Laura started filming on April 27, 1944, with a projected budget of $849,000. After Preminger took over, the film continued shooting well into late June. When released, the film was an instant hit with audiences and critics alike, earning Preminger his first Academy Award nomination for direction.

In other categories, Joseph LaShelle won the Academy Award for his cinematography while Clifton Webb and Lyle Wheeler received nominations for Best Supporting Actor and art direction respectively. The film greatly increased the profile of Gene Tierney and Dana Andrews.

Peak years

Preminger expected acclaim for Laura would promote him to work on better pictures, but his professional fate was in the hands of Zanuck, who had Preminger take over for the ailing Ernst Lubitsch on A Royal Scandal, a remake of Lubitsch's own 1924 silent Forbidden Paradise, starring Pola Negri as Catherine the Great. Before his heart attack, Lubitsch had spent months in preparation, and had already cast the film. Preminger cast Tallulah Bankhead, whom he had known since 1938 when he was directing on Broadway. Bankhead learned that his Austrian Jewish family would be barred from emigrating to the US due to immigration quotas, and she asked her father (who was Speaker of the House) to intervene to save them. He did, successfully, which earned Bankhead Preminger's loyalty. Thus when Lubitsch wanted to make the film into a vehicle for Greta Garbo, Preminger, though he would have been eager to direct the film that brought Garbo out of retirement, refused to betray Tallulah. They became good friends and got along well during filming. The film received generally lackluster reviews as the Ruritanian romance genre had become outdated, and it failed to earn back any gross revenue.

Fallen Angel (1945) was exactly what Preminger had been anticipating. In Fallen Angel, a con man and womanizer ends up by chance in a small California town, where he romances a sultry waitress and a well-to-do spinster. When the waitress is found killed, the drifter, played by Dana Andrews, becomes the prime suspect. Zanuck gave Preminger the task of convincing Alice Faye, the studio's top musical star of the late 1930s and early 1940s, to play the role of the spinster. Zanuck hoped Faye's appearance would boost the film's box-office appeal, but many of her scenes were cut, which ultimately led to her departure from Fox. Linda Darnell was given the role of the doomed waitress.

Centennial Summer (1946), Preminger's next film, would be his first to be shot entirely in color. Hoping to duplicate the success of MGM's musical Meet Me in St. Louis (1944), Zanuck enlisted both Preminger and composer Jerome Kern. The musical detailed two sisters in an idealized all-American working-class family, who become rivals over the same man. The cast included Darnell and Jeanne Crain as the dueling sisters, Cornel Wilde as the object of their affections, and veteran stars Walter Brennan, Barbara Whiting Smith, Constance Bennett, and Dorothy Gish in supporting roles. The reviews and box office draw were tepid when the film was released in July 1946, but by the end of that year Preminger had one of the most sumptuous contracts on the lot, earning $7,500 a week.

Forever Amber, based on Kathleen Winsor's internationally popular novel published in 1944, was Zanuck's next investment in adaptation. Preminger had read the book and disliked it immensely. Preminger had another best seller aimed at a female audience in mind, Daisy Kenyon. Zanuck pledged that if Preminger did Forever Amber first, he could go to town with Daisy Kenyon afterwards. Forever Amber had already been shooting for nearly six weeks when Preminger replaced director John Stahl. Zanuck had already spent nearly $2 million on the production. First, Preminger decided the script needed to be completely rewritten, and Peggy Cummins, the film's leading lady, would have to be replaced, because he regarded her to be "amateurish beyond belief". Only after turning to his revised script did Preminger learn Zanuck had already cast Linda Darnell in place of Cummins. The heroine in the novel was blonde, and Preminger was convinced it was necessary to cast a true blonde, Lana Turner, who was under contract to MGM. Zanuck protested, and was convinced that whoever played Amber would become a big star, and wanted that woman to be one of the studio's own. Zanuck had bought the book because he believed its scandalous reputation promised big box-office returns, and was not surprised when the Catholic Legion of Decency condemned the film for glamorizing a promiscuous heroine who has a child out of wedlock. Forever Amber opened to big business in October 1947, and garnered decent reviews. Preminger later recalled Forever Amber was "by far the most expensive picture I ever made and it was also the worst". Forever Amber (1947) was condemned by the Catholic Legion of Decency, which successfully lobbied 20th Century Fox to make changes to the film.

While the extended five-month shoot on Forever Amber was in progress Preminger maintained a busy schedule, working with writers on scripts for two planned projects, Daisy Kenyon and The Dark Wood; the latter was not produced. Joan Crawford starred in Daisy Kenyon (1947) alongside Dana Andrews, Ruth Warrick and Henry Fonda. Variety proclaimed the film "high powered melodrama surefire for the femme market".

After the modest success of Daisy Kenyon, Preminger, an avid careerist, saw That Lady in Ermine as a further opportunity. Betty Grable was cast opposite Douglas Fairbanks, Jr. The film had previously been another Lubitsch project, but after his sudden death in November 1947, Preminger took over. When the film opened to modest business in July 1948, it received better notices than it deserved, as reviewers scrambled to discern traces of Lubitsch's hand. Preminger's next film would be another period piece based on a literary classic, Oscar Wilde's play Lady Windermere's Fan (1897). Over the spring and early summer of 1948 Otto renovated Wilde's play into The Fan, which starred Madeleine Carroll. As Preminger expected, The Fan (1949) opened to poor notices.

Challenging taboos and censorship

Several of his films in this period broke new ground for Hollywood in tackling controversial and taboo topics, thereby challenging both the Motion Picture Association of America's Production Code of censorship and the Hollywood blacklist. The Catholic Legion of Decency condemned the comedy The Moon Is Blue (1953) on the grounds of moral standards. Based on a Broadway play which had not inspired mass protests for its use of the words "virgin" and "pregnant", the film was released without the Production Code Seal of Approval. Based on the novel by Nelson Algren, The Man with the Golden Arm (1955) was one of the first Hollywood films to deal with heroin addiction.

Later, Anatomy of a Murder (1959), with its frank courtroom discussions of rape and sexual intercourse led to the censors objecting to the use of words such as "rape", "sperm", "sexual climax" and "penetration". Preminger made but one concession (substituting "violation" for "penetration") and the picture was released with the MPAA seal, marking the beginning of the end of the Production Code. On Exodus (1960) Preminger struck a first major blow against the Hollywood blacklist by openly hiring banned screenwriter Dalton Trumbo. It is an adaptation of the Leon Uris bestseller about the founding of the state of Israel. Preminger also acted in a few movies including the World War II Luft-Stalag Commandant, Oberst von Scherbach of the German POW camp Stalag 17 (1953) directed by Billy Wilder.

From the mid-1950s, most of Preminger's films used distinctive animated titles designed by Saul Bass, and many had jazz scores. At the New York City Opera, in October 1953, Preminger directed the American premiere (in English translation) of Gottfried von Einem's opera Der Prozeß, based on Franz Kafka's novel The Trial. Soprano Phyllis Curtin headed the cast. He also adapted two operas for the screen during the decade. Carmen Jones (1954) is a reworking of the Bizet opera Carmen to a wartime African-American setting while Porgy and Bess (1959) is based on the George Gershwin opera. His two films of the early 1960s were Advise & Consent (1962): a political drama from the Allen Drury bestseller with a homosexual subtheme and The Cardinal (1963): a drama set in the Vatican hierarchy for which Preminger received his second Best Director Academy Award nomination.

Later career

Laurence Olivier, who played a police inspector in the psychological thriller Bunny Lake Is Missing (1965), which was shot in England, recalled in his autobiography Confessions of an Actor that he found Preminger a "bully". Adam West, who portrayed the lead in the 1960s Batman television series, echoes Olivier's opinion. He remembers Preminger when he worked in a guest role in the series, as being rude and unpleasant, especially when he disregarded the typical thespian etiquette of subtly cooperating when being helped to his feet in a scene by West and Burt Ward. Preminger played Mr. Freeze in the "Green Ice/Deep Freeze" episodes.

Beginning in 1965, Preminger made a string of films in which he attempted to make stories that were fresh and distinctive, but the films he made, including In Harm's Way (1965) and Tell Me That You Love Me, Junie Moon (1970), became both critical and financial flops. In 1967, Preminger released Hurry Sundown, a lengthy drama set in the U.S. South and partially intended to break cinematic racial and sexual taboos. However, the film was poorly received and ridiculed for a heavy-handed approach, and for the dubious casting of Michael Caine as an American southerner. Hurry Sundown signaled a rather precipitous decline in Preminger's reputation, as it was followed by several other films which were critical and commercial failures, including Skidoo (1968), a failed attempt at a hip sixties comedy (and Groucho Marx's last film), and Rosebud (1975), a terrorism thriller which was also widely ridiculed. Several publicized disputes with leading actors did further damage to Preminger's reputation. His last film, an adaptation of the Graham Greene espionage novel The Human Factor (1979), had financial problems and was barely released.

Preservation

The Academy Film Archive has preserved several of Otto Preminger's films, including The Man With the Golden Arm, The Moon is Blue and Advise & Consent.[11]

Personal life

Preminger and his wife Marion became increasingly estranged. He lived like a bachelor, as was the case when he met burlesque performer Gypsy Rose Lee and began an open relationship with her. Lee had already attempted to break into movie roles, but she was not taken seriously as anything more than a stripper. She appeared in B pictures in less-than-minor roles. Preminger's liaison with Lee produced a child, Erik.[12]

Lee rejected the idea of Preminger helping to support the child, and instead elicited a vow of silence from Preminger: he was not to reveal Erik's paternity to anyone, including Erik himself. Lee called the boy Erik Kirkland, after her husband, Alexander Kirkland, from whom she was separated at the time. It was not until 1966, when Preminger was 60 years old and Erik was 22 years old, that father and son finally met.

In May 1946, Marion asked for a divorce. On a trip to Mexico she had met a wealthy (and married) Swedish financier, Axel Wenner-Gren. The Premingers' divorce ended smoothly and speedily. She did not seek alimony, just personal belongings. Axel's wife, however, madly jealous of her rival, began to stalk Marion and was unwilling to grant a divorce. Marion claimed Mrs. Wenner-Gren attempted to shoot her at a post office in Mexico. Marion returned to Otto and resumed appearances as his wife, and nothing more. Preminger had begun dating Natalie Draper, a niece of Marion Davies.

While filming Carmen Jones (1954), Preminger began an affair with the film's star, Dorothy Dandridge, which lasted four years. During that period, Preminger advised her on career matters, including an offer made to Dandridge for the featured role of Tuptim in the 1956 film of The King and I. Preminger advised her to turn down the supporting role, as he believed it to be unworthy of her. She later regretted taking his advice.[13] Their affair was depicted in the HBO Pictures biopic, Introducing Dorothy Dandridge, in which Preminger was portrayed by Austrian actor Klaus Maria Brandauer.

Death

Otto Preminger died in New York City, New York in 1986, aged 80, from lung cancer while suffering from Alzheimer's disease. He was cremated and is interred in a niche in the Azalea Room of the Velma B. Woolworth Memorial Chapel at Woodlawn Cemetery, The Bronx, New York.

Filmography

- Die große Liebe (1931)

- Under Your Spell (1936)

- Danger - Love at Work (1937)

- Kidnapped (1938)

- The Pied Piper (1942)

- Clare Boothe Luce's Margin for Error (U.S.) also known as Margin for Error (UK) (1943)

- They Got Me Covered (1943)

- In the Meantime, Darling (1944)

- Laura (1944)

- A Royal Scandal (U.S.) also known as Czarina (UK) (1945)

- Fallen Angel (1945)

- Centennial Summer (1946)

- Forever Amber (1947)

- Daisy Kenyon (1947)

- The Fan (U.S.) also known as Lady Windermere's Fan (UK) (1949)

- Whirlpool (1949)

- Where the Sidewalk Ends (1950)

- The 13th Letter (1951)

- Angel Face (1953)

- Stalag 17 (1953) (acting only, directed by Billy Wilder)

- The Moon Is Blue (1953)

- Carmen Jones (1954)

- River of No Return (1954)

- The Court-Martial of Billy Mitchell (U.S.) also known as One Man Mutiny (UK) (1955)

- The Man with the Golden Arm (1956)

- Saint Joan (1957)

- Bonjour Tristesse (1958)

- Porgy and Bess (1959)

- Anatomy of a Murder (1959)

- Exodus (1960)

- Advise and Consent (1962)

- The Cardinal (1963)

- In Harm's Way (1965)

- Bunny Lake Is Missing (1965)

- Hurry Sundown (1967)

- Skidoo (1968)

- Tell Me That You Love Me, Junie Moon (1970)

- Such Good Friends (1971)

- Rosebud (1975)

- The Hobbit (1977) (voice of Elvenking)

- The Human Factor (1979)

Awards

Preminger's Anatomy of a Murder was nominated for an Academy Award for Best Picture. He was twice nominated for Best Director: for Laura and for The Cardinal. He won the Bronze Berlin Bear award for the film Carmen Jones at the 5th Berlin International Film Festival.[14]

References

- ↑

- ↑

- ↑ "RootsWeb: Database Index". Ssdi.rootsweb.ancestry.com. Retrieved 2016-07-17.

- ↑ "Otto Preminger : Biography". IMDb.com. Retrieved 2016-07-17.

- ↑ Foster Hirsch, Otto Preminger: The Man Who Would Be King, Random House LLC, 2011.

- ↑ Preminger, Otto (1977). Preminger: an autobiography. Doubleday. p. 24.

- ↑ "Academy Awards, USA". IMDb.com. Retrieved 2016-07-17.

- ↑ "Academy Awards, USA". IMDb.com. Retrieved 2016-07-17.

- ↑ Foster Hirsch Otto Preminger: The Man Who Would Be King, Random House, 2011, p. 857

- ↑ Fujiwara, Chris, The World and Its Double: The Life and Work of Otto Preminger. New York: Macmillan, 2009; ISBN 0-86547-995-X, p. 34

- ↑ "Preserved Projects". Academy Film Archive. Retrieved November 12, 2016.

- ↑ "Gypsy Rose Lee biography". Gypsyroselee.net. Retrieved 2016-07-17.

- ↑ "Dorothy Dandridge Profile". tcm.com.

- ↑ "5th Berlin International Film Festival: Prize Winners". berlinale.de. Retrieved 2009-12-24.

Further reading

- Journals

- Denby, David (2008-01-14). "Balance Of Terror: How Otto Preminger made his movies". The New Yorker. New York, NY: Condé Nast Publications. Retrieved 2011-09-18.

- Rich, Nathaniel (2008-11-06). "The Deceptive Director". The New York Review of Books. New York, NY. Retrieved 2011-09-18.

- Books

- Carluccio, Giulia; Cena, Linda (1990). Otto Preminger (in Italian). Firenze: Nuova Italia. OCLC 24409124.

- Frischauer, Willi (1973). Behind the Scenes of Otto Preminger: An Unauthorised Biography. London, UK: Joseph. ISBN 978-0-7181-1170-0.

- Fujiwara, Chris (2008). The World and Its Double: The Life and Work of Otto Preminger. New York: Faber and Faber. ISBN 978-0-571-22370-1.

- Grob, Norbert; Aurich, Rolf; Jacobsen, Wolfgang (1999). Otto Preminger (in German). Berlin: Jovis. ISBN 978-3-931321-59-8.

- Hirsch, Foster (2007). Otto Preminger: The Man Who Would Be King. New York: Alfred A. Knopf. ISBN 978-0-375-41373-5.

- Legrand, Gérard; Lourcelles, Jacques; Mardore, Michel (1993). Otto Preminger (in French). Paris: Cinémathèque Française. ISBN 978-2-87340-089-7.

- Lourcelles, Jacques (1965). Otto Preminger (in French). Paris: Seghers. OCLC 2910388.

- Pratley, Gerald (1971). The Cinema of Otto Preminger. New York: A.S. Barnes & Co. ISBN 978-0-498-07860-6.

- Preminger, Otto (1977). Preminger: An Autobiography. Garden City, NY: Doubleday. ISBN 978-0-385-03480-7.

- Interviews

- Preminger, Otto (1967-04-10). "Censorship and the Production Code: Otto Preminger". Firing Line (Interview). Interview with William F. Buckley, Jr. New York, NY: WWOR-TV. Retrieved 2011-09-25.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Otto Preminger. |

- Otto Preminger at the Internet Movie Database

- Otto Preminger at the Internet Broadway Database

- Cinema Retro: Keir Dullea Recalls Starring in Preminger's Bunny Lake is Missing

- Literature on Otto Preminger

- Otto Preminger interview on BBC Radio 4 Desert Island Discs, February 8, 1980

| Preceded by George Sanders |

Mr. Freeze Actor 1966 |

Succeeded by Eli Wallach |