Ludwig Maximilian University of Munich

| Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität München | |

| |

| Latin: Universitas Ludovico-Maximilianea Monacensis | |

| Type | Public |

|---|---|

| Established | 1472 (as University of Ingolstadt until 1802) |

| Rector | Bernd Huber |

Administrative staff | 16,943; 747 Professors (as of WS 2013/2014) |

| Students | 50,542 (as of WS 2013/2014; 15% international) |

| Location | Munich, Germany |

| Nobel Laureates | 34 |

| Colours | Green and White |

| Affiliations |

German Excellence Universities LERU |

| Website |

www |

| |

Ludwig-Maximilian University of Munich (also referred to as LMU or the University of Munich, in German: Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität München) is a public research university located in Munich, Germany.

The University of Munich is among Germany's oldest universities. Originally established in Ingolstadt in 1472 by Duke Ludwig IX of Bavaria-Landshut, the university was moved in 1800 to Landshut by King Maximilian I of Bavaria when Ingolstadt was threatened by the French, before being relocated to its present-day location in Munich in 1826 by King Ludwig I of Bavaria. In 1802, the university was officially named Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität by King Maximilian I of Bavaria in his as well as the university's original founder's honour.[1]

The University of Munich has, particularly since the 19th century, been considered as one of Germany's as well as one of Europe's most prestigious universities; with 36 Nobel laureates associated with the university, it ranks 17th worldwide by number of Nobel laureates. Among these were Wilhelm Röntgen, Max Planck, Werner Heisenberg, Otto Hahn and Thomas Mann. Pope Benedict XVI was also a student and professor at the university. The LMU has recently been conferred the title of "elite university" under the German Universities Excellence Initiative.

LMU is currently the second-largest university in Germany in terms of student population; in the winter semester of 2013/2014, the university had a total of 50,542 matriculated students. Of these, 8,719 were freshmen while international students totalled 7,403 or almost 15% of the student population. As for operating budget, the university records in 2013 a total of 571.3 million Euros in funding without the university hospital; with the university hospital, the university has a total funding amounting to approximately 1.5 billion Euros.[2][3]

History

1472–1800

The university was founded with papal approval in 1472 as the University of Ingolstadt (foundation right of Louis IX the Rich), with faculties of philosophy, medicine, jurisprudence and theology. Its first rector was Christopher Mendel of Steinfels, who later became bishop of Chiemsee.

In the period of German humanism, the university's academics included names such as Conrad Celtes and Petrus Apianus. The theologian Johann Eck also taught at the university. From 1549 to 1773, the university was influenced by the Jesuits and became one of the centres of the Counter-Reformation. The Jesuit Petrus Canisius served as rector of the university.

At the end of the 18th century, the university was influenced by the Enlightenment, which led to a stronger emphasis on natural science.

1800–1933

In 1800, the Prince-Elector Maximilianv IV Joseph (the later Maximilian I, King of Bavaria) moved the university to Landshut, due to French aggression that threatened Ingolstadt during the Napoleonic Wars. In 1802, the university was renamed the Ludwig Maximilian University in honour of its two founders, Louis IX, Duke of Bavaria and Maximilian I, Elector of Bavaria. The Minister of Education, Maximilian von Montgelas, initiated a number of reforms that sought to modernize the rather conservative and Jesuit-influenced university. In 1826, it was moved to Munich, the capital of the Kingdom of Bavaria. The university was situated in the Old Academy until a new building in the Ludwigstraße was completed. The locals were somewhat critical of the amount of Protestant professors Maximilian and later Ludwig I invited to Munich. They were dubbed the "Nordlichter" (Northern lights) and especially physician Johann Nepomuk von Ringseis was quite angry about them.[4]

In the second half of the 19th century, the university rose to great prominence in the European scientific community, attracting many of the world's leading scientists. It was also a period of great expansion. From 1903, women were allowed to study at Bavarian universities, and by 1918, the female proportion of students at LMU had reached 18%. In 1918, Adele Hartmann became the first woman in Germany to earn the Habilitation (higher doctorate), at LMU.

During the Weimar Republic, the university continued to be one of the world's leading universities, with professors such as Wilhelm Röntgen, Wilhelm Wien, Richard Willstätter, Arnold Sommerfeld and Ferdinand Sauerbruch.

1943–1945

During the Third Reich, academic freedom was severely curtailed. In 1943 the White Rose group of anti-Nazi students conducted their campaign of opposition to the National Socialists at this university.

1945–present

The university has continued to be one of the leading universities of West Germany during the Cold War and in the post-reunification era. In the late 1960s, the university was the scene of protests by radical students.

Today the University of Munich is part of 24 Collaborative Research Centers funded by the German Research Foundation (DFG) and is host university of 13 of them. It also hosts 12 DFG Research Training Groups and three international doctorate programs as part of the Elite Network of Bavaria. It attracts an additional 120 million euros per year in outside funding and is intensively involved in national and international funding initiatives.

LMU Munich has a wide range of degree programs, with 150 subjects available in numerous combinations. 15% of the 45,000 students who attend the university come from abroad.

In 2005, Germany’s state and federal governments launched the German Universities Excellence Initiative, a contest among its universities. With a total of 1.9 billion euros, 75 percent of which comes from the federal state, its architects aim to strategically promote top-level research and scholarship. The money is given to more than 30 research universities in Germany.

The initiative will fund three project-oriented areas: graduate schools to promote the next generation of scholars, clusters of excellence to promote cutting-edge research and "future concepts" for the project-based expansion of academic excellence at universities as a whole. In order to qualify for this third area, a university had to have at least one internationally recognized academic center of excellence and a new graduate school.

After the first round of selections, LMU Munich was invited to submit applications for all three funding lines: It entered the competition with proposals for two graduate schools and four clusters of excellence.

On Friday 13 October 2006, a blue-ribbon panel announced the results of the Germany-wide Excellence Initiative for promoting top university research and education. The panel, composed of the German Research Foundation and the German Science Council, has decided that LMU Munich will receive funding for all three areas covered by the Initiative: one graduate school, three "excellence clusters" and general funding for the university’s "future concept".

In January 2012, scientists at the Ludwig Maximilian University, published details of the most sensitive listening device known so far. This has led to the college being inducted into the Guinness book of world records.[5]

Campus

_(14_06_2005).jpg)

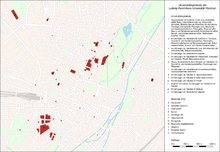

LMU's institutes and research centers are spread throughout Munich, with several buildings located in the suburbs of Oberschleissheim and Garching as well as Maisach and Bad Tölz. The university's main buildings are grouped around Geschwister-Scholl-Platz and Professor-Huber-Platz on Ludwigstrasse, extending into side streets such as Akademiestraße, Schellingstraße, and Veterinärstraße. Other large campuses and institutes are located in Großhadern (Klinikum Großhadern), Martinsried (chemistry and biotechnology campus), the Ludwigsvorstadt (Klinikum Innenstadt) and in the Lehel (Institut am Englischen Garten), across from the main buildings, through the Englischer Garten.

The university's main building is situated in Geschwister-Scholl-Platz and the university's main campus is served by the Munich subway's Universität station.

Academics

Subjects and fields of study

Despite the Bologna Process which saw the demise of most traditional academic degree courses such as the Diplom and Magister Artium in favour of the more internationally known Bachelors and Masters system, the University of Munich continues to offer more than 100 areas of study with numerous combinations of majors and minors.[6]

In line with the university's internationalisation as a popular destination for tertiary studies, an increasing number of courses mainly at the graduate and post-graduate levels are also available in English to cater to international students who may have little or no background in the German language.[7] Some notable subject areas which currently offer programmes in English include various fields of psychology, physics as well as business and management. A list of current programmes offered in English can be accessed directly from the university's international website while a complete list of courses offered across all academic levels can be found here.[8]

Faculties

The university consists of 18 faculties which oversee various departments and institutes.[9] The official numbering of the faculties and the missing numbers 06 and 14 are the result of breakups and mergers of faculties in the past. The Faculty of Forestry operations with number 06 has been integrated into the Technical University of Munich in 1999 and faculty number 14 has been merged with faculty number 13.[10][11][12]

- 01 Faculty of Catholic Theology

- 02 Faculty of Protestant Theology

- 03 Faculty of Law

- 04 Faculty of Business Administration

- 05 Faculty of Economics

- 07 Faculty of Medicine

- 08 Faculty of Veterinary Medicine

- 09 Faculty for History and the Arts

- 10 Faculty of Philosophy, Philosophy of Science and Study of Religion

- 11 Faculty of Psychology and Educational Sciences

- 12 Faculty for the Study of Culture

- 13 Faculty for Languages and Literatures

- 15 Faculty of Social Sciences

- 16 Faculty of Mathematics, Computer Science and Statistics

- 17 Faculty of Physics

- 18 Faculty of Chemistry and Pharmacy

- 19 Faculty of Biology

- 20 Faculty of Geosciences and Environmental Sciences

Research centres

In addition to its 18 faculties, the University of Munich also maintains numerous research centres involved in numerous cross-faculty and transdisciplinary projects to complement its various academic programmes.[13] Some of these research centres were a result of cooperation between the university and renowned external partners from academia and industry; the Rachel Carson Center for Environment and Society, for example, was established through a joint initiative between LMU Munich and the Deutsches Museum, while the Parmenides Center for the Study of Thinking resulted from the collaboration between the Parmenides Foundation and LMU Munich's Human Science Center.[14]

Some of the research centres which have been established include:

- Center for Integrated Protein Science Munich (CIPSM)

- Helmholtz Zentrum München – German Research Center for Environmental Health

- Nanosystems Initiative Munich (NIM)

- Parmenides Center for the Study of Thinking

- Rachel Carson Center for Environment and Society

Tuition and Fees

As of October 2016, universities in Bavaria do not raise a tuition fee (2007-2013, a tuition of €300-€500 was collected). However, a basic contribution to the state-run Studentenwerk of €52 a semester and a mandatory off-hours public transportation semester ticket (for the Munich Transport and Tariff Association, MVV) of €65 have to be paid. For €189 additionally, a full network pass is then optionally available. This mixed model (€117 or €306) is the result of several years of negotiations to allow students to get an affordable semester ticket despite the high costs of regular tickets in Munich. The current package was accepted by an overwhelming majority of 86,3% of students across all Munich universities in 2012 and introduced in the 2013 winter term.[15]

Rankings

| University rankings | |

|---|---|

| Global | |

| ARWU[16] | 61 |

| Times[17] | 29 |

| QS[18] | 75 |

| Europe | |

| ARWU[19] | 15 |

| Times[20] | 10 |

| QS[21] | 25 |

LMU Munich is consistently ranked among the world's top 100 universities in various international ranking surveys such as the Academic Ranking of World Universities and the Times Higher Education Supplement which ranks over 1000 universities worldwide. In a 2010 human competitiveness index & analysis Human Resources & Labor Review published in Chasecareer Network, LMU Munich was the only German university listed in its list of the world's best 50 universities and was ranked 38th internationally.[22] In 2013, LMU Munich was internationally ranked 53rd in the QS World University Rankings.[23]

Notable rival German universities in terms of rankings include TU München, Humboldt University, Heidelberg University and the Free University of Berlin.

Notable alumni and faculty members

The alumni of Ludwig Maximilian University of Munich played a major role in the development of quantum mechanics. Max Planck, the founder of quantum theory and Nobel laureate in Physics in 1918, was an alumnus of the university. Founders of quantum mechanics such as Werner Heisenberg, Wolfgang Pauli, and others were associated with the university. Most recently, to honor the Nobel laureate in Chemistry Gerhard Ertl, who worked as a professor at the University of Munich from 1973–1986, the building of the Physical Chemistry was named after him.

Sir Muhammad Iqbal a great philosopher, regarded as the Shair-e-Mashriq (شاعر المشرق, "Poet of the East"),[24][25][26] also called Muffakir-e-Pakistan (مفکر پاکستان, "The Thinker of Pakistan") and Hakeem-ul-Ummat (حکیم الامت, "The Sage of the Ummah"), moved to Germany in 1907, to study doctorate and earned PhD degree from the Ludwig Maximilian University, Munich in 1908. Working under the guidance of Friedrich Hommel, Iqbal published his doctoral thesis in 1908 entitled: The Development of Metaphysics in Persia.[25][27][28][29]

The anti-Nazi resistance White Rose was based in this university.[30]

Pope Benedict XVI was a student and professor at LMU Munich

Pope Benedict XVI was a student and professor at LMU Munich Wilhelm Conrad Röntgen received the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1901

Wilhelm Conrad Röntgen received the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1901 Theodor W. Hänsch received the Nobel Prize in Physics in 2005

Theodor W. Hänsch received the Nobel Prize in Physics in 2005 Nobel Prize winning novelist Thomas Mann was a student at LMU Munich

Nobel Prize winning novelist Thomas Mann was a student at LMU Munich Werner Heisenberg received the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1932

Werner Heisenberg received the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1932 Philosopher, Persian and Urdu Poet, Sir Muhammad Iqbal Studied Philosophy at LMU Munich

Philosopher, Persian and Urdu Poet, Sir Muhammad Iqbal Studied Philosophy at LMU Munich Hans-Werner Sinn, professor of economics at LMU Munich

Hans-Werner Sinn, professor of economics at LMU Munich Konrad Adenauer was Chancellor of Germany from 1949 to 1963

Konrad Adenauer was Chancellor of Germany from 1949 to 1963

The sociologist Max Weber was a professor at LMU Munich

The sociologist Max Weber was a professor at LMU Munich

University halls

Great Assembly Hall (Große Aula)

The große Aula is located in the university main building at Ludwigstraße in Munich. The Aula was constructed as part of the main building by Friedrich von Gärtner and completed in 1840. The hall is situated in the first floor and extends to the second floor.

The Aula was not destroyed during World War II and, thus, one of few usable post war venues in Munich. Hence, the Aula was used for the first performances of concerts after the war. Furthermore, it was venue for the constituent assembly of the state of Bavaria, where the current bavarian constitution was enacted.[31]

Today, the Aula hosts mainly concerts, talks and lectures.

See also

- Education in Germany

- List of forestry universities and colleges

- List of modern universities in Europe (1801–1945)

- List of universities in Germany

References

- ↑ "Landshut (1800 - 1826) - LMU München". Uni-muenchen.de. Retrieved 2011-10-28.

- ↑ "Zahlen und Fakten - LMU München". Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität München. Retrieved 2014-10-03.

- ↑ "Klinikum Universität München // Jahresbericht 2013". Klinikum der Universität München. Retrieved 2014-10-03.

- ↑ Wortgewaltiger Gegner der Nordlichter: Der Mediziner Johann Nepomuk von Ringseis, in: Ulrike Leutheusser, Heinrich Nöth (Hg.), „Dem Geist alle Tore öffnen". König Maximilian II. von Bayern und die Wissenschaft, München 2009, 142-153; 2. Aufl. München 2011, 142-153.

- ↑ Glenday, Craig. Guiness Book of World Records. p. 194. ISBN 978-1-908843-15-9.

- ↑ "Herzlich willkommen! - LMU München". Uni-muenchen.de. Retrieved 2011-10-28.

- ↑ "Degree Students - LMU Munich". En.uni-muenchen.de. Retrieved 2011-10-28.

- ↑ "Studienfächer und Studiengänge von A bis Z - LMU München". Uni-muenchen.de. Retrieved 2011-10-28.

- ↑ "Faculties - LMU Munich". En.uni-muenchen.de. Retrieved 2011-10-28.

- ↑ "Geschichte der forstwissenschaftlichen Ausbildung in Bayern". Technische Universität München. Retrieved 2010-01-06.

- ↑ "Fakultäten". web.archive.org. Archived from the original on 2 March 2007. Retrieved 2010-01-06.

- ↑ Andreas C. Hofmann: Warum die LMU München (keine) 20 Fakultäten hat. Zur Ausdifferenzierung des Wissens an der Ludovico-Maximilianea im Spiegel der Geschichte ihrer Fakultäten, in: aventinus bavarica Nr. 15 [29. Mai 2010], http://www.aventinus-online.de/no_cache/persistent/artikel/7838.

- ↑ "Research Centers - LMU Munich". En.uni-muenchen.de. Retrieved 2011-10-28.

- ↑ "About us " MCA " EUNICE " Education " Parmenides Foundation". Parmenides-foundation.org. Retrieved 2011-10-28.

- ↑ "Semesterticket München". Semesterticket-muenchen.de. Retrieved 2013-01-09.

- ↑ "Academic Ranking of World Universities: Global". Institute of Higher Education, Shanghai Jiao Tong University. 2016. Retrieved September 8, 2016.

- ↑ "World University Rankings 2016-2017". Times Higher Education. 2015. Retrieved October 22, 2016.

- ↑ "QS World University Rankings 2016/17". Quacquarelli Symonds Limited. 2016. Retrieved September 8, 2016.

- ↑ "Academic Ranking of World Universities: Global". Institute of Higher Education, Shanghai Jiao Tong University. 2016. Retrieved September 8, 2016.

- ↑ "Best universities in Europe 2017". The Times Higher Education. 2016. Retrieved October 22, 2016.

- ↑ "QS World University Rankings". QS Quacquarelli Symonds Limited. 2016. Retrieved September 8, 2016.

- ↑ "300 Best World Universities 2010". ChaseCareer Network.

- ↑ "QS World University Rankings". Topuniversities. Retrieved 2011-10-28.

- ↑ Samiuddin, Abida (2007). Encyclopaedic dictionary Of Urdu literature (2 Vols. Set). Global Vision Publishing House. p. 304. ISBN 81-8220-191-8.

- 1 2 Sharif, Imran (21 April 2011). "Allama Iqbal's 73rd death anniversary observed with reverence". Pakistan Today. Retrieved 6 August 2012.

- ↑ "Cam Diary: Oxford remembers the Cam man". Daily Times. 28 May 2003. Archived from the original on 6 May 2005. Retrieved 9 November 2010.

- ↑ Lansing, East; H-Bahai, Mi. (2001) [1908]. "The development of metaphysics in persia" (PDF). London Luzac and Company. Retrieved 1 May 2012.

- ↑ Mir, Mustansir (1990). Tulip in the desert: A selection of the poetry of Muhammad Iqbal. c.Hurts and Company, Publishers Ltd. London. p. 2. ISBN 978-967-5-06267-4.

- ↑ Jackso, Roy (2006). Fifty key figures in Islam. Routledge. p. 181. ISBN 978-0-415-35467-7.

- ↑ "DenkStätte Weiße Rose". Weisse rose Stiftung e.V. Retrieved 2016-09-22.

- ↑ "Geschichte der Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität München". innovations-report.de. Retrieved 2010-10-05.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität München. |

- University of Munich Website (German)

- University of Munich Website (English)

- 360° Panorama at the Ludwig Maximilians University

Coordinates: 48°09′03″N 11°34′49″E / 48.15083°N 11.58028°E