Mace (weapon)

A mace is a blunt weapon, a type of club or virge that uses a heavy head on the end of a handle to deliver powerful blows. A mace typically consists of a strong, heavy, wooden or metal shaft, often reinforced with metal, featuring a head made of stone, copper, bronze, iron, or steel.

The head of a military mace can be shaped with flanges or knobs to allow greater penetration of plate armour. The length of maces can vary considerably. The maces of foot soldiers were usually quite short (two or three feet, or seventy to ninety centimetres). The maces of cavalrymen were longer and thus better suited for blows delivered from horseback. Two-handed maces could be even larger.

Maces are rarely used today for actual combat, but a large number of government bodies (for instance, the British House of Commons and the U.S. Congress), universities and other institutions have ceremonial maces and continue to display them as symbols of authority. They are often paraded in academic, parliamentary or civic rituals and processions.

Prehistory

The mace was developed during the Upper Paleolithic from the simple club, by adding sharp spikes of flint or obsidian.

In Europe, an elaborately carved ceremonial flint mace head was one of the artifacts discovered in excavations of the Neolithic mound of Knowth in Ireland, and Bronze Age archaeology cites numerous finds of perforated mace heads.

In ancient Ukraine, stone mace heads were first used nearly eight millennia ago. The others known were disc maces with oddly formed stones mounted perpendicularly to their handle. The Narmer Palette shows a king swinging a mace. See the articles on the Narmer Macehead and the Scorpion Macehead for examples of decorated maces inscribed with the names of kings.

The problem with early maces was that their stone heads shattered easily and it was difficult to fix the head to the wooden handle reliably. The Egyptians attempted to give them a disk shape in the predynastic period (about 3850–3650 B.C.) in order to increase their impact and even provide some cutting capabilities, but this seems to have been a short-lived improvement.

A rounded pear form of mace head known as a "piriform" replaced the disc mace in the Naqada II period of pre-dynastic Upper Egypt (3600–3250 B.C.) and was used throughout the Naqada III period (3250-3100 B.C.). Similar mace heads were also used in Mesopotamia around 2450–1900 B.C. The Assyrians used maces probably about nineteenth century B.C. and in their campaigns; the maces were usually made of stone or marble and furnished with gold or other metals, but were rarely used in battle unless fighting heavily armoured infantry.

An important, later development in mace heads was the use of metal for their composition. With the advent of copper mace heads, they no longer shattered and a better fit could be made to the wooden club by giving the eye of the mace head the shape of a cone and using a tapered handle.

The Shardanas or warriors from Sardinia who fought for Ramses II against the Hittities were armed with maces consisting of wooden sticks with bronze heads. Many bronze statuettes of the times show Sardinian warriors carrying swords, bows and original maces.

Antiquity

The usage of maces in warfare is also described in the ancient Indian epics Ramayana and Mahabarata. Unique types of maces known as "gada" were used extensively in ancient Indian warfare, and the enchanted talking mace Sharur made its first appearance in Sumerian/Akkadian mythology during the epic of Ninurta.

The ancient Romans did not make wide use of maces, probably because of the influence of armour, and due to the nature of the Roman infantry's fighting style which involved the pilum (spear) and the gladius (short sword used in a stabbing fashion). The use of a heavy swinging-arc weapon in the well-disciplined tight formations of the Roman infantry would not have been practical. Though auxiliaries from Syria Palestina were armed with clubs and maces at the battles of Immae and Emesa in 272 CE. They proved highly effective against the heavily armoured horsemen of Palmyra.

Persians used a variety of maces. Unlike Romans, Persians fielded large numbers of heavily armoured and armed cavalry (see cataphracts). For a heavily armed Persian knight, a mace was as effective as a sword or battle axe. In fact, Shahnameh has many references to heavily armoured knights facing each other using maces, axes, and swords.

European Middle Ages

During the Middle Ages metal armour such as mail protected against the blows of edged weapons. Solid metal maces and war hammers proved able to inflict damage on well armoured knights, as the force of a blow from a mace is great enough to cause damage without penetrating the armour. Though iron became increasingly common, copper and bronze were also used, especially in iron-deficient areas. The Sami, for example, continued to use bronze for maces as a cheaper alternative to iron or steel swords.

One example of a mace capable of penetrating armour is the flanged mace. The flanges allow it to dent or penetrate thick armour. Flange maces did not become popular until after knobbed maces. Although there are some references to flanged maces (bardoukion) as early as the Byzantine Empire c. 900[1] it is commonly accepted that the flanged mace did not become popular in Europe until the 12th century, when it was concurrently developed in Russia and Mid-west Asia.

Maces, being simple to make, cheap, and straightforward in application, were quite common weapons. Examples found in museums are often highly decorated.

It is popularly believed that maces were employed by the clergy in warfare to avoid shedding blood[2] (sine effusione sanguinis). The evidence for this is sparse and appears to derive almost entirely from the depiction of Bishop Odo of Bayeux wielding a club-like mace at the Battle of Hastings in the Bayeux Tapestry, the idea being that he did so to avoid either shedding blood or bearing the arms of war. The fact that his brother Duke William carries a similar item suggests that, in this context, the mace may have been simply a symbol of authority.[3] Certainly, other bishops were depicted bearing the arms of a knight without comment, such as Archbishop Turpin who bears both a spear and a sword named "Almace" in The Song of Roland or Bishop Adhemar of Le Puy, who also appears to have fought as a knight during the First Crusade, an expedition that Odo also joined.[4]

Eastern Europe

Maces were very common in eastern Europe, especially medieval Poland, Ukraine.[5] Eastern European maces often had pear shaped heads. These maces were also used by the Moldavian king Stephen the Great in some of his wars (see Bulawa).

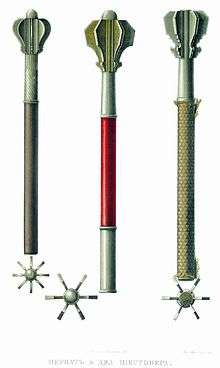

The Pernach was a type of flanged mace developed since the 12th century in the region of Kievan Rus', and later widely used throughout the whole of Europe. The name comes from the Slavic word pero (перо) meaning feather, reflecting the form of pernach that resembled a fletched arrow. Pernachs were the first form of the flanged mace to enjoy a wide usage. It was well suited to penetrate plate armour and chain mail. In the later times it was often used as a symbol of power by the military leaders in Eastern Europe.[6]

Pre-Columbian America

The cultures of pre-Columbian America used clubs and maces extensively. The warriors of the Moche state and the Inca Empire used maces with bone, stone or copper heads and wooden shafts.

Indian Subcontinent

Shishpar

The word Shishpar, originates from the Indo-Iranian word used for sharp edged mountains in the Hindu Kush, the Shishpar mace introduced by the Delhi Sultanate and continued to be utilized until the 18th century.

.jpg) Indian shishpar (flanged mace), all steel construction, with eight knife edged, hinged flanges, 18th-19th century, 26 inches long.

Indian shishpar (flanged mace), all steel construction, with eight knife edged, hinged flanges, 18th-19th century, 26 inches long._3.jpg) Indian shishpar (flanged mace), steel with solid shaft and eight flanged head, 24in.

Indian shishpar (flanged mace), steel with solid shaft and eight flanged head, 24in. Indian (Deccan) tabar-shishpar, an extremely rare combination tabar axe and shishpar eight flanged mace, steel with hollow shaft, 21.75 in. 17th to 18th century.

Indian (Deccan) tabar-shishpar, an extremely rare combination tabar axe and shishpar eight flanged mace, steel with hollow shaft, 21.75 in. 17th to 18th century.

Mace as exercise equipment

Indian akharas (i.e. combat training gymnasiums) often use a heavy stone gada as a part of their training.

Modern era

Trench raiding clubs used during World War I were modern variations on the medieval mace. They were homemade mêlée weapons used by both the Allies and the Central Powers. Clubs were used during night time trench raiding expeditions as a quiet and effective way of killing or wounding enemy soldiers.

Makeshift maces were also found in the possession of some football hooligans in the 1980s.[7]

Ceremonial use

Maces have had a role in ceremonial practices over time, including some still in use today.

Parliamentary maces

Ceremonial maces are important in many parliaments following the Westminster system. They are carried in by the sergeant-at-arms or some other mace-bearers and displayed on the clerks' table while parliament is in session to show that a parliament is fully constituted. They are removed when the session ends. The mace is also removed from the table when a new speaker is being elected to show that parliament is not ready to conduct business.

Ecclesiastical maces

The ceremonial mace is a short, richly ornamented staff often made of silver, the upper part of which is furnished with a knob or other head-piece and decorated with a coat of arms. The ceremonial mace was commonly borne before eminent ecclesiastical corporations, magistrates, and academic bodies as a mark and symbol of jurisdiction.

Parade maces

Maces are also used as a parade item, rather than a tool of war, notably in military bands. Specific movements of the mace from the Drum Major will signal specific orders to the band they lead. The mace can signal anything from a step-off to a halt, from the commencement of playing to the cut off.

University maces

University maces are employed in a manner similar to Parliamentary maces. They symbolize the authority and independence of a chartered university and the authority vested in the provost. They are typically carried in at the beginning of a convocation ceremony and are often less than half a meter high.

Heraldic use

Like many weapons from feudal times, maces have been used in heraldic blazons as either a charge on a shield or other item, or as external ornamentation.

Thus, in France:

- the city of Cognac (in the Charente département): Argent on a horse sable harnessed or a man proper vested azure with a cloak gules holding a mace, on a chief France modern

- the city of Colmar (in Haut-Rhin): per pale gules and vert a mace per bend sinister or. Three maces, probably a canting device (Kolben means mace in German, cfr. Columbaria the Latin name of the city) appear on a 1214 seal. The arms in a 15th-century stained-glass window show the mace per bend on argent.

- the duke of Retz (a pairie created in 1581 for Albert de Gondy) had Or two maces or clubs per saltire sable, bound gules

- the Garde des sceaux ('keeper of the seals', still the formal title of the French Republic's Minister of Justice) places behind the shield, two silver and gilded maces in saltire, and the achievement is surmounted by a mortier (magistrate's hat)

See also

Notes

- ↑ Heath, Ian. Armies of the Byzantine Empire, 886–1118.

- ↑ Disraeli, Isaac (1834). Curiosities of Literature, Volume 1. Boston: Lilly, Wait, Colman, and Holden.

- ↑ It is also possible that William was simply armed with a mace as was his brother Odo and other knights. See the following images of William, an unidentified companion and Odo carrying mace-like objects in the Bayeux Tapestry

- ↑ Much of the popularity of this view can be attributed to the Dungeons and Dragons game, which in early editions limited its cleric class to bludgeoning weapons, at first influenced by the popular belief, and later on to balance the game by reducing the class's power in battle, a rule that was widely imitated.

- ↑ Official Symbols of the President of Ukraine: The presidential mace

- ↑ Medieval flanged maces by Shawn M. Caza.

- ↑ "Mace of Evil". Daily Mirror. 27 March 1986. p. 1.

References

- Dictionary of Medieval Knighthood and Chivalry by Bradford Broughton (NY, Greenwood Press, 1986, ISBN 0-313-24552-5)

- Hafted Weapons in Medieval and Renaissance Europe: The Evolution of European Staff Weapons Between 1200 and 1650 by John Waldman (Brill, 2005, ISBN 90-04-14409-9)

- Medieval Military Technology by Kelly DeVries (Broadview Press, 1998, 0-921149-74-3)

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Maces. |

-

Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). "Mace". Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). "Mace". Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company. - The Hunt Museum (enter "Mace" in Keyword in Description)

- Heraldica.org