Mann Gulch fire

|

Mann Gulch Wildfire Historic District | |

|

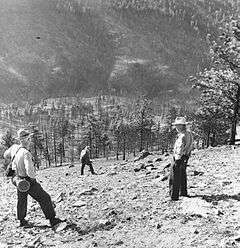

Investigators stand on the steep, now barren, north slope of Mann Gulch. | |

| |

| Nearest city | Helena, Montana |

|---|---|

| Area | 1,195 acres (484 ha) |

| Built | 1949 |

| NRHP Reference # | 99000596[1] |

| Added to NRHP | May 19, 1999 |

The Mann Gulch fire was a wildfire reported on August 5, 1949 in a gulch located along the upper Missouri River in the Gates of the Mountains Wilderness, Helena National Forest, in the state of Montana in the United States. A team of 15 smokejumpers parachuted into the area on the afternoon of August 5, 1949 to fight the fire, rendezvousing with a former smokejumper who was employed as a fire guard at the nearby campground. As the team approached the fire to begin fighting it, unexpected high winds caused the fire to suddenly expand, cutting off the men's route and forcing them back uphill. During the next few minutes, a "blow-up" of the fire covered 3,000 acres (1,200 ha) in ten minutes, claiming the lives of 13 firefighters, including 12 of the smokejumpers. Only three of the smokejumpers survived. The fire would continue for five more days before being controlled.

The United States Forest Service drew lessons from the tragedy of the Mann Gulch fire by designing new training techniques and safety measures that developed how the agency approached wildfire suppression. The agency also increased emphasis on fire research and the science of fire behavior.

University of Chicago English professor and author Norman Maclean (1902–1990) researched the fire and its behavior for his book, Young Men and Fire (1992) which was published after his death.[2] Maclean, who worked northwestern Montana in logging camps and for the forest service in his youth, recounted the events of the fire and ensuing tragedy and undertook a detailed investigation of the fire's causes. Young Men and Fire won the National Book Critics Circle Award for non-fiction in 1992.[3] The 1952 film, Red Skies of Montana starring actor Richard Widmark and directed by Joseph M. Newman was loosely based on the events of the Mann Gulch fire.[2]:p.155

The location of the Mann Gulch fire was included as a historical district on the United States National Register of Historic Places on May 19, 1999.[1]

Sequence of events

The fire started when lightning struck the south side of Mann Gulch at the Gates of the Mountains, a canyon over five miles long that cuts through a series of 1,200 foot cliffs.[4][5] The place was noted and named by Lewis and Clark on their journey west in 1805.[6] The fire was spotted by forest ranger James O. Harrison around noon on August 5, 1949. Harrison, a college student at Montana State University, was working the summer as recreation and fire prevention guard for the Meriwether Canyon Campground. The previous year he had been a smokejumper but had given it up because of the danger.[7] As a ranger he still had a responsibility to watch for and help fight fires, but it was not his primary role.[8] On this day he fought the fire on his own for four hours before he met the crew of smokejumpers who had been dispatched from Hale Field, Missoula, Montana, in a C-47.

It was hot, with a temperature of 97 °F, and the fire danger rating was high, rated 74 out of a possible 100.[2]:p.42[5][9] Wind conditions that day were turbulent. One smokejumper got sick on the way and did not jump, returning with the airplane to Hale Field. Getting off the plane he resigned from the smokejumpers. In all, 15 smokejumpers parachuted into the fire. Their radio was destroyed during the jump, after its parachute failed to open, while other gear and individual jumpers were scattered widely due to the conditions.[10] After the smokejumpers had landed a shout was heard coming from the front of the fire. Foreman Wagner Dodge went ahead to find the person shouting and to scout the fire. He left instructions for the team to finish gathering their equipment and eat, then cross the gully to the south slope and advance to the front of the fire. The voice turned out to be Jim Harrison, who had been fighting the fire by himself for the past four hours.[5][11]

The two headed back, Dodge noting that you could not get closer to within 100 feet of the fire due to the heat. The crew met Dodge and Harrison about half way to the fire. Dodge instructed the team to move off the front of the fire and down the gully, crossing back over to the thinly forested and grass covered north slope of the gulch, "sidehilling" (keeping the same contour or elevation) and moving "down gulch" towards the Missouri River. They could then fight the fire from the flank or behind, steering the fire to a low fuel area. Dodge returned with Harrison up the gulch to the supply area, where the two stopped to eat before returning for the all-night work of fighting the fire. While there Dodge noticed the smoke along the fire front boiling up, indicating an intensification of the heat of the fire. He and Harrison headed down the gulch to catch up with the crew.

The "Blow Up"

By the time Dodge reached his men, the fire at the bottom of the gulch was already jumping from the high south slope of Mann Gulch to the bottom of the north side of the gulch. As the fire jumped across to the bottom of the north slope the intense heat of the fire combined with wind coming off the river and pushed the flames up gulch into the fast burning north slope grass, causing what fire fighters call a "blow up". The crew could not see the bottom of the gulch, the various side ridges running down the slope obscuring their view, and they initially continued down the side of the ridge. When Dodge finally got a glimpse of what was happening below, he turned the men around and started them angling back up the side of the ridge. Within a couple hundred yards he ordered the men to drop packs and heavy tools (Pulaskis, shovels and crosscut saws):

Dodge's order was to throw away just their packs and heavy tools, but to his surprise some of them had already thrown away all of their heavy equipment. On the other hand, some of them wouldn't abandon their heavy tools, even after Dodge's order. Diettert, one of the most intelligent of the crew, continued carrying both his tools until Rumsey caught up with him, took his shovel and leaned it against a pine tree. Just a little further on, Rumsey and Sallee pass the recreation guard, Jim Harrison, who, having been on the fire all afternoon, was now exhausted. He was sitting with his heavy pack on and was making no effort to take it off[2]:p.42[12]

By this point the fire was moving extremely fast up the 76% north slope (37.23 degree slope) of Mann gulch and Dodge realized they would not be able to make the ridge line in front of the fire. With the fire less than a hundred yards behind he took a match out and set fire to the grass just before them. In doing so he was attempting to create an escape fire to lie in so that the main fire would burn around him and his crew. In the back draft of the main fire the grass fire set burned straight up toward the ridge above. Turning to the three men by him, Robert Sallee, Walter Rumsey and Eldon Diettert, Dodge said "Up this way", but the men misunderstood him. The three ran straight up for the ridge crest, moving up along the far edge of Dodge's fire. Sallee later said he wasn't sure what Dodge was doing, and thought perhaps he intended the fire to act as a buffer between the men and the main fire. It was not until he got to the ridge crest and looked back down that he realized what Dodge had intended. As the rest of the crew came up Dodge tried to direct them through the fire he had set and into the center burnt out area. Dodge later stated that someone, possibly squad leader William Hellman, said "To hell with that, I'm getting out of here". The rest of the team raced on past Dodge up the side of the slope toward the hogback of Mann Gulch ridge, hoping they had enough time to get through the rock ridge line and over to safer ground on the other side. None of the men racing up before the fire entered into the escape fire.

Immediate outcome

Four of the men reached the ridge crest, but only two, Bob Sallee and Walter Rumsey, managed to escape through a crevice or deep fissure in the rock ridge to reach the other side. In the dense smoke of the fire the two had no way of knowing if the crevice they found actually "went through" to the other side or would be a blind trap. Diettert had been just to the right, slightly upgulch of Sallee and Rumsey, but he did not drop back to the crevice and continued on up the right side of the hogback. He did not find another escape route and was overtaken by the fire. Sallee and Rumsey came through the hogback to the ridge crest above what became known as Rescue Gulch. Dropping down off the ridge they managed to find a rock slide with little to no vegetation. They waited there for the fire to overtake them, moving from the bottom of the slide to the top as the fire moved past. Hellman was caught by the fire on the top of the ridge and was badly burned. Though he and Joseph Sylvia initially survived the fire, they suffered heavy injuries and both died in hospital the next day. Wag Dodge entered the charred center of the escape fire he had built and survived the intensely burning main fire.[10]

In Young Men and Fire, Maclean stated that when the fire passed over Dodge's position, "he was lifted off the ground two or three times."[2]:p.106 Later researchers repeated the claim.[10] However, this statement was an exaggeration. Dodge actually wrote, in his statement to the board of review, "There were three extreme gusts of hot air that almost lifted me from the ground as the fire passed over" [13][14] In another description of Dodge's ordeal, John Maclean said, "as the main fire passed, it [the fire] picked him up and shook him like a dog with a bone."[15]

Although Young Men and Fire attributed the story to Earl Cooley, the spotter and kicker aboard the airplane,[14]:p.83 it actually originated with C.E. "Mike" Hardy, who was the head of the litter bearers collecting the bodies the day after the disaster.[16] Hardy assisted Norman Maclean in his research and accompanied him on a trip to the site.[2]:p.157

It was originally thought that the unburned patches underneath the bodies indicated they had suffocated for lack of air before the fire caught them.[17] This is another fallacy. In modern fire science, the unburned patches are called protected areas.[18] The firefighters' bodies protected these areas by shielding from the intense thermal radiation, by keeping out hot gases, and absorbing heat. All of these factors kept the grass and forest litter unburned where they were laying. It is now known that death by smoke and toxic gas inhalation, while common in structure fires because of the confined atmosphere, is virtually nonexistent among wildland fire fatalities.[19]

Timing

The events described above all transpired in a relatively short period of time. Everyone had jumped by around 4:10 p.m. The scattered cargo had been gathered at about 5:00 p.m. At about 5:45 p.m., the crew had seen the fire coming up towards them on the north slope and had turned to run. By four minutes to 6:00, the fire had swept over them. The time at which the fire engulfed the men was judged by the melted hands on Harrison's pocketwatch, forever frozen at 5:56 p.m. by the intense heat. Studies estimated that the fire covered 3,000 acres in 10 minutes during this blow-up stage, an hour and 45 minutes after they had arrived. Thirteen firefighters died, with eleven killed in the fire itself and two who sustained fatal burns. Only three of the sixteen survived.

Findings

Casualties

Those that were killed by the fire:

- Robert J. Bennett, age 22, from Paris, Tennessee

- Eldon E. Diettert, age 19, from Moscow, Idaho, died on his 19th birthday

- James O. Harrison, Helena National Forest Fire Guard, age 20, from Missoula, Montana

- William J. Hellman, age 24, from Kalispell, Montana

- Philip R. McVey, age 22, from Babb, Montana

- David R. Navon, age 28, from Modesto, California

- Leonard L. Piper, age 23, from Blairsville, Pennsylvania

- Stanley J. Reba, from Brooklyn, New York

- Marvin L. Sherman, age 21, from Missoula, Montana

- Joseph B. Sylvia, age 24, from Plymouth, Massachusetts

- Henry J. Thol, Jr., age 19, from Kalispell, Montana

- Newton R. Thompson, age 23, from Alhambra, California

- Silas R. Thompson, age 21, from Charlotte, North Carolina

Those that survived:

- R. Wagner (Wag) Dodge, Missoula SJ foreman, age 33 at the time of the fire. Wag died 5 years after the fire from Hodgkin's disease.

- Walter B. Rumsey, age 21 at time of the fire, from Larned, Kansas. Rumsey died in an airplane crash in 1980, age 52.

- Robert W. Sallee, youngest man on the crew, age 17 at time of the fire, from Willow Creek, Montana. Last survivor of the smoke jumpers. Died May 29, 2014.

Much controversy surrounded Foreman Dodge and the fire he lit to escape. In answering the questions of the Forest Service Review Board as to why he took the actions he did, Dodge stated he had never heard of such a fire being set; it had just seemed "logical" to him. In fact, it was not a method that the forest service had considered, nor would it work in the intense heat of the normal tall growth forest fires that they typically fought. Similar types of escape fires had been used by the plains Indians to escape the fast-moving, brief duration grass fires of the plains, and the method had been written about by James Fenimore Cooper (1827) in The Prairie, but in this case Foreman Dodge appears to have invented it on the spot, as the only means available to him to save his crew. None of the men realized what it was and only Dodge was saved by it.

Earl Cooley was the spotter/kicker the morning of the August 5, 1949 Mann Gulch fire jump. Cooley was the first Smokejumper to jump on an operational fire jump. The first jump was a two-man jump, and was performed on July 12, 1940. Mr. Cooley was the airborne supervisor who directed the crew of smokejumpers who dropped in to fight the Mann Gulch fire. In the 1950s Mr. Cooley served as the smokejumper base superintendent and was the first president of the National Smokejumper Association. Mr. Cooley died November 9, 2009, at age 98.

The C-47/DC-3, registration number NC24320, was the only smokejumper plane available at Hale Field, near the current location of Sentinel High School, on August 5, 1949, when the call came in seeking 25 smokejumpers to fight a blaze in a hard-to-reach area of the Helena National Forest. The C-47/DC-3 could only hold 16 jumpers and their equipment. Even though more help was needed, fire bosses decided not to wait for a second plane, and instead sent No. NC24320 out on its own. NC24320 flew with Johnson Flying Service from Hale Field in Missoula, Montana and was used to drop Smokejumpers as well as for other operations for which Johnson Flying Service held contracts. The C-47/DC-3 that carried the smokejumpers that day is on exhibit in Missoula at the Museum of Mountain Flying. The aircraft was restored and now serves as a memorial to the Smokejumpers and the Fire Guard that lost their lives at Mann Gulch on August 5, 1949.

Aftermath

Four hundred fifty men fought for five more days to get the fire under control, which had spread to 4,500 acres (1,800 ha).

Wagner Dodge survived unharmed and died five years later of Hodgkin's disease.

Thirteen crosses were erected to mark the locations where the thirteen firefighters who died fighting the Mann Gulch Fire fell. However, one of the smokejumpers who died in the Mann Gulch Fire was David Navon, who was Jewish. In 2001 the cross marking the location where Navon died was replaced with a marker bearing a Star of David[20]

Several months following the fire, fire scientist Harry Gisborne, from the U.S. Forest Service Research Center at Priest River, came to examine the damage. Despite a history of heart problems, he nevertheless conducted an on-ground survey of the fire site. He suffered a heart attack and died while finishing the day's research. Gisborne had forwarded theories as to the cause of the blowup prior to his arrival on site. Once there, he discovered several conditions, which caused him to change his concepts of fire activity, particularly those pertaining to fire "blow-ups". He noted this to his companion just before his death on November 9, 1949.

There was some controversy about the fire, with a few parents of the men trying to sue the government. One charge was that the "escape fire" had actually burned the men.

Lessons learned from the Mann Gulch fire had a significant effect on firefighter training. Two training protocols—"Ten Standard Firefighting Orders" and "Eighteen Situations That Shout Watch Out"—were incorporated into Forest Service firefighter training program, and safety training made mandatory to achieve certification to work on a fire line. However, the training methodology proved inadequate and the tragedy would be repeated twice, in the 1990 Dude fire in Arizona, which killed six firefighters, and in the 1994 South Canyon Fire in Colorado, in which 14 firefighters died. A primary factor in the latter appeared to be surprise of the sudden transition from surface fire to crown fire, leading to the development and adoption of LCES, an acronym for a four-point safety procedure to increase observance of the previous training protocols. LCES consists of posting Lookouts, providing all firefighters radio Communication with lookouts, identifying Escape routes, and designating valid Safety zones, and ensuring that all members of the process, from "hotshot" crews to seasonal Type 2 crew volunteers to "crew bosses", understand and follow its tenets.[21]

Contributing factors

Several factors that combined to create the disaster are described in Norman MacLean's book Young Men and Fire.

- Slope — Fire spreads faster up a slope, and the north slope of Mann Gulch was about a 75% incline. Slope also makes it very difficult to run.

- Fuel — Fire spreads fast in dry grass. The north slope of Mann Gulch was mostly knee high cheatgrass, an especially volatile fuel, and the entire area had been left ungrazed because it had been recently designated a wildlife area and closed to local cattle.

- Leadership — Dodge did not know most of the crew, as he had been doing base maintenance work during the normal training and "get acquainted" time of the season. This may have contributed to the crew not trusting his "escape fire." Furthermore, Dodge left his crew for several minutes, during which the second-in-command let them spread out instead of staying together.

- Communication — The crew's single radio broke because its parachute failed to open. It could have possibly prevented the disaster or helped to get aid more quickly to the two burned men who died later. There were other dangerous fires going on at the same time and Forest Service leaders did not know what was happening on Mann Gulch.

- Weather — The season was very dry and that day was extremely hot. Winds in the Gulch were also strong "up gulch'" the same direction in which the men tried to run.

Young Men and Fire

The Mann Gulch fire was the subject of Norman Maclean's book Young Men and Fire,[22] which was published after his death. The book won the National Book Critics Circle Award for non-fiction in 1992.

Norman Maclean's son John wrote a book in 2003 titled Fire and Ashes: On the Front Lines Battling Wildfires, and it also includes a section on the Mann Gulch Fire. In 2004, John N. Maclean also published an article called "Fire and Ashes: The Last Survivor of the Mann Gulch Fire," in Montana: The Magazine of Western History. The article was adapted from the Mann Gulch section of his book, in which he interviewed Bob Sallee, the last remaining survivor of the fire.[23]

Folk songs

James Keelaghan wrote a song about this fire entitled "Cold Missouri Waters" after being inspired by Young Men and Fire. The song was covered by Richard Shindell, Dar Williams, and Lucy Kaplansky on their album Cry Cry Cry. It was also covered by Hank Cramer in his album, Days Gone By. It was again recorded by Paul McKenna Band on their 2012 album ”Elements”. A cover version also appears on the 2014 album ”The Call”, by Greg Russell and Ciaran Algar. In 2016, Irish singer Pauline Scanlon covered the song on her album Gossamer. It is sung from the perspective of foreman Dodge, lying on his deathbed dying of Hodgkin's disease five years after the fire. It imagines Dodge saying of his decision to set the escape fire:

"I don't know why, I just thought it. I struck a match to waist-high grass, running out of time. Tried to tell them, 'Step into this fire I set. We can't make it, this is the only chance you'll get.' But they cursed me, ran for the rocks above instead. I lay face down and prayed above the cold Missouri waters."

Ross Brown, a musician/songwriter from Townsend, MT (about 35 miles south of Helena) wrote another song entitled "The Mann Gulch." A scratch version of this song is available on YouTube.

The song also has been recorded on Black Irish Band's album "Into the Fire" released in 2007. The album is all songs about firefighters. The album also features Michael Martin Murphey. Underneath Montana Skies is another song about the Mann Gulch fire [24] written by Patrick Michael Karnahan also on this album.

See also

- List of wildfires

- Red Skies of Montana — a movie based on this incident

References

- 1 2 National Park Service (9 July 2010). "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Maclean, Norman. Young Men and Fire (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1993). ISBN 0-226-50061-6

- ↑ National Book Critics Circle. All Past National Book Critics Circle Award Winners and Finalists. Retrieved July 31, 2013.

- ↑ "Montana Bureau of Mines and Geology: Lewis and Clark in Montana — a geologic perspective". Retrieved 2014-07-07.

- 1 2 3 Weick, Karl E. (1993). "The Collapse of Sensemaking in Organizations: The Mann Gulch Disaster". Administrative Science Quarterly. 38 (4): 628–652. doi:10.2307/2393339. JSTOR 2393339.

- ↑ "Survey of Historic Sites and Buildings: Gates of the Rocky Mountains". Retrieved 2014-07-07.

- ↑ "US FOrest Service History, Mann Gulch Fire". Retrieved 2014-07-07.

- ↑ Matthews, Mark (2007). A Great Day to Fight a Fire: Mann Gulch, 1949. University Of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-8061-3857-2., p. 31

- ↑ Lillquist, Karl (2006). "Teaching with catastrophe: Topographic map interpretation and the physical geography of the 1949 Mann Gulch, Montana wildfire" (PDF). Journal of Geoscience Education. 54 (5): 561–571. Retrieved June 16, 2013.

- 1 2 3 Rothermel, Richard C. "The Mann Gulch Fire: A Race That Couldn't be Won" (PDF). Gen. Tech. Rep. INT-299. USDA Forestry Service. Retrieved June 17, 2013.

- ↑ Turner, Dave (1999). "The Thirteenth Fire" (PDF). Forest History Today (Spring): 26–28. Retrieved June 16, 2013.

- ↑ Weick, Karl E. (1996). "Drop Your Tools: An Allegory for Organizational Studies". Administrative Science Quarterly. 41 (2): 301–313. doi:10.2307/2393722. JSTOR 2393722.

- ↑ Anon (August 14, 1949). "Dodge Describes Tragedy of Fire Fighters". The Missoulian. p. 1.

- 1 2 Cooley, Earl (1984). Trimotor and trail. Missoula: Mountain Press Publishing Co. p. 98. ISBN 0-87842-173-4.

- ↑ Maclean, John (2004). Fire and Ashes. New York, NY: Owl Books/Henry Holt and Company LLC. p. 180. ISBN 0-8050-7591-7.

- ↑ Alexander, Martin E.; Ackerman, Mark Y.; Baxter, Gregory J. "An Analysis of Dodge's Escape Fire on the 1949 Mann Gulch Fire in Terms of a Survival Zone for Wildland Firefighters" (PDF). Wildland Fire Information. FireWhat, Incorporated. Retrieved July 16, 2015.

- ↑ Lillquist, Karl (November 2006). "Teaching with Catastrophe: Topographic Map Interpretation and the Physical Geography of the 1949 Mann Gulch, Montana Wildfire". Journal of Geoscience Education. 54 (5): 561–571.

- ↑ Anon (2014). NFPA 921, Guide for Fire and Explosion Investigations. Quincy, MA: National Fire Protection Association. pp. 62–63. ISBN 978-145590862-2.

- ↑ Shusterman, Dennis; Kaplan, Jerold Z.; Canabarro, Carla (February 1993). "Immediate Health Effects of an Urban Wildfire". Western Journal of Medicine. 158: 133–138.

- ↑ A Star for David

- ↑ Matthews (2007), pp. 222-225

- ↑ Norman Maclean, Young Men and Fire (excerpt), 1992. Retrieved February 28, 2007.

- ↑ Maclean, John N. (2004). "Fire + Ashes: The Last Survivor of The Mann Gulch Fire". Montana: The Magazine of Western History. 54 (3): 18–33. Retrieved October 25, 2006.

- ↑ /http://www.cdbaby.com/cd/blackirishband7

External resources

- Wildfire Lesson From Mann Gulch fire

- Maclean, Norman (1992). Young Men and Fire. University Of Chicago Press. ISBN 0-226-50061-6.

- Maclean, John (2003). Fire and Ashes: On the Front Lines Battling Wildfires. Owl Books. ISBN 0-8050-7591-7.

- Rothermel, Richard C. (May 1993). Mann Gulch Fire: A Race That Couldn't Be Won. United States Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Intermountain Research Station, General Technical Report INT-GTR-299.

- Turner, Dave. Spring 1999. "The Thirteenth Fire". Forest History Today.

- Weick, Karl E. (1993). "The Collapse of Sensemaking in Organizations: The Mann Gulch Disaster". Administrative Science Quarterly. 38 (4): 628–652. doi:10.2307/2393339. JSTOR 2393339.

- Matthews, Mark (2007). A Great Day to Fight a Fire: Mann Gulch, 1949. University Of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-8061-3857-2.

- "August 5, 1949: Mann Gulch Tragedy". Peeling Back the Bark blog, the Forest History Society.

External links

- Vecchione, Judith. "Fire Wars". NOVA Transcripts Fire Wars PBS. Retrieved July 16, 2015.

- Mann Gulch Fire, 1949, a history of the Mann Gulch Fire from the Forest History Society website.

- Mann Gulch Virtual Field Trip

- Satellite map of Mann Gulch, showing a forest fire in progress (via Google Maps)

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Mann Gulch. |

Coordinates: 46°52′47″N 111°54′18″W / 46.8796°N 111.9049°W