Etiquette

Etiquette (/ˈɛtᵻˌkɛt/ or /ˈɛtᵻkᵻt/, French: [e.ti.kɛt]) is a code of behavior that delineates expectations for social behavior according to contemporary conventional norms within a society, social class, or group.

The French word étiquette, literally signifying a tag or label, was used in a modern sense in English around 1750.[2] Etiquette has changed and evolved over the years.

History

In the 3rd millennium BC, Ptahhotep wrote The Maxims of Ptahhotep. The Maxims were conformist precepts extolling such civil virtues as truthfulness, self-control and kindness towards one's fellow beings. Learning by listening to everybody and knowing that human knowledge is never perfect are a leitmotif. Avoiding open conflict wherever possible should not be considered weakness. Stress is placed on the pursuit of justice, although it is conceded that it is a god's command that prevails in the end. Some of the maxims refer to one's behaviour when in the presence of the great, how to choose the right master and how to serve him. Others teach the correct way to lead through openness and kindness. Greed is the base of all evil and should be guarded against, while generosity towards family and friends is deemed praiseworthy.

Confucius (551–479 BC) was a Chinese teacher, editor, politician, and philosopher whose philosophy emphasized personal and governmental morality, correctness of social relationships, justice and sincerity.

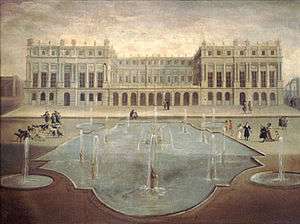

Louis XIV (1638–1718) "transformed a royal hunting lodge in Versailles, a village 25 miles southwest of the capital, into one of the largest palaces in the world, officially moving his court and government there in 1682. It was against this awe-inspiring backdrop that Louis tamed the nobility and impressed foreign dignitaries, using entertainment, ceremony and a highly codified system of etiquette to assert his supremacy.”[3]

Politeness

During the Enlightenment era, a self-conscious process of the imposition of polite norms and behaviours became a symbol of being a genteel member of the upper class. Upwardly mobile middle class bourgeoisie increasingly tried to identify themselves with the elite through their adopted artistic preferences and their standards of behaviour. They became preoccupied with precise rules of etiquette, such as when to show emotion, the art of elegant dress and graceful conversation and how to act courteously, especially with women. Influential in this new discourse was a series of essays on the nature of politeness in a commercial society, penned by the philosopher Lord Shaftesbury in the early 18th century. Shaftesbury defined politeness as the art of being pleasing in company:

- 'Politeness' may be defined a dext'rous management of our words and actions, whereby we make other people have better opinion of us and themselves.[4]

Periodicals, such as The Spectator, founded as a daily publication by Joseph Addison and Richard Steele in 1711, gave regular advice to its readers on how to conform to the etiquette required of a polite gentleman. Its stated goal was "to enliven morality with wit, and to temper wit with morality...to bring philosophy out of the closets and libraries, schools and colleges, to dwell in clubs and assemblies, at tea-tables and coffeehouses" It provided its readers with educated, topical talking points, and advice in how to carry on conversations and social interactions in a polite manner.[5]

The allied notion of 'civility' - referring to a desired social interaction which valued sober and reasoned debate on matters of interest - also became an important quality for the 'polite classes'.[6] Established rules and procedures for proper behaviour as well as etiquette conventions, were outlined by gentlemen's clubs, such as Harrington's Rota Club. Periodicals, including The Tatler and The Spectator, infused politeness into English coffeehouse conversation, as their explicit purpose lay in the reformation of English manners and morals.[7]

It was Philip Stanhope, 4th Earl of Chesterfield who first used the word 'etiquette' in its modern meaning, in his Letters to His Son on the Art of Becoming a Man of the World and a Gentleman.[8] This work comprised over 400 letters written from 1737 or 1738 and continuing until his son's death in 1768, and were mostly instructive letters on various subjects.[9] The letters were first published by his son's widow Eugenia Stanhope in 1774. Chesterfield endeavoured to decouple the issue of manners from conventional morality, arguing that mastery of etiquette was an important weapon for social advancement. The Letters were full of elegant wisdom and perceptive observation and deduction. Chesterfield epitomised the restraint of polite 18th-century society, writing, for instance, in 1748:

I would heartily wish that you may often be seen to smile, but never heard to laugh while you live. Frequent and loud laughter is the characteristic of folly and ill-manners; it is the manner in which the mob express their silly joy at silly things; and they call it being merry. In my mind there is nothing so illiberal, and so ill-bred, as audible laughter. I am neither of a melancholy nor a cynical disposition, and am as willing and as apt to be pleased as anybody; but I am sure that since I have had the full use of my reason nobody has ever heard me laugh.

By the Victorian era, etiquette had developed into an exceptionally complicated system of rules, governing everything from the proper method for writing letters and using cutlery to the minutely regulated interactions between different classes and gender.[10]

Manners

Manners is a term usually preceded by the word good or bad to indicate whether or not a behavior is socially acceptable. Every culture adheres to a different set of manners, although a lot of manners are cross‐culturally common. Manners are a subset of social norms which are informally enforced through self-regulation and social policing and publicly performed. They enable human ‘ultrasociality’ [11] by imposing self-restraint and compromise on regular, everyday actions.

Sociology perspectives

In his book The Civilizing Process, Norbert Elias [12] argued that manners arose as a product of group living and persist as a way of maintaining social order. He theorized that manners proliferated during the Renaissance in response to the development of the ‘absolute state’ – the progression from small group living to the centralization of power by the state. Elias believed that the rituals associated with manners in the Court Society of England during this period were closely bound with social status. To him, manners demonstrate an individual’s position within a social network and act as a means by which the individual can negotiate that position.

Petersen and Lupton argue that manners helped reduce the boundaries between the public sphere and the private sphere and gave rise to “a highly reflective self, a self who monitors his or her behavior with due regard for others with whom he or she interacts socially.” They explain that that; “The public behavior of individuals came to signify their social standing, a means of presenting the self and of evaluating others and thus the control of the outward self was vital.” [13] From this perspective, manners are seen not just as a means of displaying one’s social status, but also as a means of maintaining social boundaries relative to class and identity.

Pierre Bourdieu’s notion of ‘habitus’ can also contribute to the understanding of manners.[14] The habitus, he explains, is a set of ‘dispositions’ that are neither self‐determined, nor pre‐determined, by external environmental factors. They tend to operate at a subconscious level and are “inculcated through experience and explicit teaching” [15] and produced and reproduced by social interactions. Manners, in this view, are likely to be a central part of the ‘dispositions’ which guide an individual’s ability to make socially compliant behavioral decisions.

Anthropology perspectives

Anthropologists concern themselves primarily with detailing cultural variances and differences in ‘ways of seeing’. Theorists such as Mary Douglas have claimed that each culture’s unique set of manners, behaviors and rituals enable the local cosmology to remain ordered and free from those things that may pollute or defile it.[16] In particular, she suggests that ideas of pollution and disgust are attached to the margins of socially acceptable behavior to curtail such actions and maintain“ the assumptions by which experience is controlled.”

Evolutionary biology perspectives

Evolutionary biology looks at the origin of behavior and the motivation behind it. Charles Darwin analyzed the remarkable universality of facial responses to disgust, shame and other complex emotions.[17] Having identified the same behavior in young infants and blind individuals he concluded that these responses are not learned but innate. According to Val Curtis,[18] the development of these responses was concomitant with the development of manners behavior. For Curtis, manners play an evolutionary role in the prevention of disease. This assumes that those who were hygienic, polite to others and most able to benefit from their membership within a cultural group, stand the best chance of survival and reproduction.

Catherine Cottrell and Steven Neuberg explore how our behavioral responses to ‘otherness’ may enable the preservation of manners and norms.[19] They suggest that the foreignness or unfamiliarity we experience when interacting with different cultural groups for the first time, may partly serve an evolutionary function: “Group living surrounds one with individuals able to physically harm fellow group members, to spread contagious disease, or to “free ride” on their efforts. A commitment to sociality thus carries a risk: If threats such as these are left unchecked, the costs of sociality will quickly exceed its benefits. Thus, to maximize the returns on group living, individual group members should be attuned to others’ features or behaviors.”[19]

Thus, people who possess similar traits, common to the group, are to be trusted, whereas those who do not are to be considered as ‘others’ and treated with suspicion or even exclusion. Curtis argues that selective pressure borne out of a shift towards communal living would have resulted in individuals being shunned from the group for hygiene lapses or uncooperative behavior. This would have led to people avoiding actions that might result in embarrassment or others being disgusted.[20] Joseph Henrich and Robert Boyd developed a model to demonstrate this process at work. They explain natural selection has favored the acquisition of genetically transmitted learning mechanisms that increase an individual’s chance of acquiring locally adaptive behavior. They hypothesize that: “Humans possess a reliably developing neural encoding that compels them both to punish individuals who violate group norms (common beliefs or practices) and punish individuals who do not punish norm violators.”[21] From this approach, manners are a means of mitigating undesirable behavior and fostering the benefits of in‐group cooperation.

Types

Curtis also specifically outlines three manner categories; hygiene, courtesy and cultural norms, each of which help to account for the multifaceted role manners play in society.[20] These categories are based on the outcome rather than the motivation of manners behavior and individual manner behaviors may fit in to 2 or more categories.

Hygiene Manners – are any manners which affect disease transmission. They are likely to be taught at an early age, primarily through parental discipline, positive behavioral enforcement of continence with bodily fluids (such as toilet training), and the avoidance or removal of items that pose a disease risk for children. It is expected that, by adulthood, hygiene manners are so entrenched in one’s behavior that they become second nature. Violations are likely to elicit disgust responses.

Courtesy Manners – demonstrate one’s ability to put the interests of others before oneself; to display self‐control and good intent for the purposes of being trusted in social interactions. Courtesy manners help to maximize the benefits of group living by regulating social interaction. Disease avoidance behavior can sometimes be compromised in the performance of courtesy manners. They may be taught in the same way as hygiene manners but are likely to also be learned through direct, indirect (i.e. observing the interactions of others) or imagined (i.e. through the executive functions of the brain) social interactions. The learning of courtesy manners may take place at an older age than hygiene manners, because individuals must have at least some means of communication and some awareness of self and social positioning. The violation of courtesy manners most commonly results in social disapproval from peers.

Cultural Norm Manners – typically demonstrate one’s identity within a specific socio‐cultural group. Adherence to cultural norm manners allows for the demarcation of socio‐cultural identities and the creation of boundaries which inform who is to be trusted or who is to be deemed as ‘other’. Cultural norm manners are learnt through the enculturation and routinisation of ‘the familiar’ and through exposure to ‘otherness’ or those who are identified as foreign or different. Transgressions and non‐adherence to cultural norm manners commonly result in alienation. Cultural norms, by their very nature, have a high level of between‐group variability but are likely to be common to all those who identify with a given group identity.

Rules of etiquette encompass most aspects of social interaction in any society, though the term itself is not commonly used. A rule of etiquette may reflect an underlying ethical code, or it may reflect a person's fashion or status. Rules of etiquette are usually unwritten, but aspects of etiquette have been codified from time to time.

Books

Erasmus of Rotterdam published his book On Good Manners for Boys in 1530. Amid his advice for young children on fidgeting, yawning, bickering and scratching he highlights that a core tenet of manners is the ability to “readily ignore the faults of others but avoid falling short yourself”.[22]

In centuries since then, many authors have tried to collate manners or etiquette guide books. One of the most famous of these was Emily Post who began to document etiquette in 1922. She described her work as detailing the “trivialities” of desirable everyday conduct but also provided descriptions of appropriate conduct for key life events such as baptisms, weddings and funerals. She later established an institute which continues to provide updated advice on how to negotiate modern day society with good manners and decorum. The most recent edition of her book provides advice on such topics as when it is acceptable to ‘unfriend’ someone on Facebook and who is entitled to which armrest when flying.[23] Etiquette books such as these as well as those by Amy Vanderbilt,[24] Hartley,[25] Judith Martin,[26] and Sandi Toksvig[27] outline suggested behaviours for a range of social interactions. However, all note that to be a well-mannered person one must not merely read their books but be able to employ good manners fluidly in any situation that may arise.

Western office and business

The etiquette of business is the set of written and unwritten rules of conduct that make social interactions run more smoothly. Office etiquette in particular applies to coworker interaction, excluding interactions with external contacts such as customers and suppliers. When conducting group meetings in the United States, the assembly might follow Robert's Rules of Order, if there are no other company policies to control a meeting.

These rules are often echoed throughout an industry or economy. For instance, 49% of employers surveyed in 2005 by the American National Association of Colleges and Employers found that non-traditional attire would be a "strong influence" on their opinion of a potential job candidate.[28] Business Etiquette at companies such as IBM influence global business etiquette and professional standards.[29]

Both office and business etiquette overlap considerably with basic tenets of netiquette, the social conventions for using computer networks.

Business etiquette can vary significantly in different countries, which is invariably related to their culture. For example: A notable difference between Chinese and Western business etiquette is conflict handling. Chinese businesses prefer to look upon relationship management to avoid conflicts[30] - stemming from a culture that heavily relies on guanxi (personal connections) - while the west leaves resolution of conflict to the interpretations of law through contracts and lawyers.

Adjusting to foreign etiquettes is a major complement of culture shock, providing a market for manuals.[31] Other resources include business and diplomacy institutions, available only in certain countries such as the UK.[32]

In 2011, a group of etiquette experts and international business group formed a non-profit organization called IITTI (pronounced as "ET") to help human resource (HR) departments of multinationals in measuring the etiquette skills of prospective new employees during the recruitment process by standardizing image and etiquette examination, similar to what ISO does for industrial process measurements.[33]

Etiquette in retail is sometimes summarized as "The customer is always right."

There are always two sides to the case, of course, and it is a credit to good manners that there is scarcely ever any friction in stores and shops of the first class. Salesmen and women are usually persons who are both patient and polite, and their customers are most often ladies in fact as well as "by courtesy." Between those before and those behind the counters, there has sprung up in many instances a relationship of mutual goodwill and friendliness. It is, in fact, only the woman who is afraid that someone may encroach upon her exceedingly insecure dignity, who shows neither courtesy nor consideration to any except those whom she considers it to her advantage to please.Emily Post Etiquette 1922

International

Europe

European etiquette is not uniform. Even within the regions of Europe, etiquette may not be uniform: within a single country there may be differences in customs, especially where there are different linguistic groups, as in Switzerland where there are French, German, and Italian speakers.

Japan

The Japanese are very formal. Moments of silence are far from awkward. Smiling does not always mean that the individual is expressing pleasure. Business cards are to be handed out formally following this procedure: Hand card with writing facing upwards; bow when giving and receiving the card; grasp it with both hands; read it carefully; and put it in a prominent place. The Japanese feel a “Giri,” an obligation to reciprocate a gesture of kindness. They also rely on an innate sense of right and wrong.

| Conversation | Business | Dining | Leisure |

|---|---|---|---|

|

• Bow when greeting someone. • Do not display emotion. • Do not blow your nose in public. • Do not stand with your hands in your pocket. • Displaying an open mouth is rude. |

• Bow in greeting. • Females should avoid heels. • Do not stash away a business card in a pocket or in a place where it is likely to be misplaced or damaged. • Look at the business card when given, and try to say something genuinely nice about it (colors, font, raised lettering, etc.). The card should also be received with two hands. • Exchange business cards. • Moments of silence are normal. • Do not slouch. • Cross legs at the ankles. • Do not interrupt but listen carefully. • Do not chew gum. |

• It is acceptable to make noise while eating. • Food is judged by not only the taste but also the consistency. • Do not mix sake with any other alcohol. • Try any food that is given to you. • Finishing all the rice in your bowl indicates the desire for second helpings. • If someone offers you sake, drink. |

• Remove shoes before entering homes and restaurants. • To beckon a person extend hand palm down and make a scratching motion. • The Japanese wear surgical masks when they have a cold. • Men sit cross-legged and women sit on their legs or with their legs to the side. |

Kenya

Kenyans believe that their tribal identity is very important. Kenyans are also very nationalistic. Kenyans rarely prefer to be alone, and are usually very friendly and welcoming of guests. Kenyans are very family-oriented.

| Conversation | Business | Dining | Leisure |

|---|---|---|---|

| • The handshake is the common greeting. | • Use right hand to receive gifts. | • Eating is taken very seriously. | • You must ask permission in taking pictures of people. |

| • Engage in small talk. | • Personal references are highly respected. | • Eating is usually done in silence. | • Kenyans operate on 'Swahili Time'. |

| • Kenyans do not like to say "No" or "Yes". | • Meetings can be very lengthy. | ||

| • Be humorous. | • Hand out business cards. | • The evening meal tends to be heavy. | |

| • Laugh readily. | • Decisions tend to be made in a group. | • Traditional foods are eaten without cutlery by using the right hand. | |

Cultural differences

Etiquette is dependent on culture; what is excellent etiquette in one society may shock another. Etiquette evolves within culture. The Dutch painter Andries Both shows that the hunt for head lice (illustration, right), which had been a civilized grooming occupation in the early Middle Ages, a bonding experience that reinforced the comparative rank of two people, one groomed the other, one was the subject of the groomer, had become a peasant occupation by 1630. The painter portrays the familiar operation matter-of-factly, without the disdain this subject would have received in a 19th-century representation.

Etiquette can vary widely between different cultures and nations. For example, in Hausa culture, eating while standing may be seen as offensively casual and ill-omened behavior, insulting the host and showing a lack of respect for the scarcity of food—the offense is known as "eating with the devil" or "committing santi." In China, a person who takes the last item of food from a common plate or bowl without first offering it to others at the table may be seen as a glutton who is insulting the host's generosity. Traditionally, if guests do not have leftover food in front of them at the end of a meal, it is to the dishonour of the host. In the United States of America, a guest is expected to eat all of the food given to them, as a compliment to the quality of the cooking. However, it is still considered polite to offer food from a common plate or bowl to others at the table.

In such rigid hierarchal cultures as Korea and Japan, alcohol helps to break down the strict social barrier between classes. It allows for a hint of informality to creep in. It is traditional for host and guest to take turns filling each other's cups and encouraging each other to gulp it down. For someone who does not consume alcohol (except for religious reasons), it can be difficult escaping the ritual of the social drink.[34]

Etiquette is a topic that has occupied writers and thinkers in all sophisticated societies for millennia, beginning with a behavior code by Ptahhotep, a vizier in ancient Egypt's Old Kingdom during the reign of the Fifth Dynasty king Djedkare Isesi (c. 2414–2375 BC). All known literate civilizations, including ancient Greece and Rome, developed rules for proper social conduct. Confucius included rules for eating and speaking along with his more philosophical sayings.

Early modern conceptions of what behavior identifies a "gentleman" were codified in the 16th century, in a book by Baldassare Castiglione, Il Cortegiano ("The Courtier"); its codification of expectations at the court of Urbino remained in force in its essentials until World War I. Louis XIV established an elaborate and rigid court ceremony, but distinguished himself from the high bourgeoisie by continuing to eat, stylishly and fastidiously, with his fingers. An important book about etiquette is Il Galateo by Giovanni della Casa; in fact, in Italian, etiquette is generally called galateo (or etichetta or protocollo).

In the American colonies, Benjamin Franklin and George Washington wrote codes of conduct for young gentlemen. The immense popularity of advice columns and books by Letitia Baldrige and Miss Manners shows the currency of this topic. Even more recently, the rise of the Internet has necessitated the adaptation of existing rules of conduct to create Netiquette, which governs the drafting of e-mail, rules for participating in an online forum, and so on.

In Germany, many books dealing with etiquette, especially dining, dressing etc., are called the Knigge, named after Adolph Freiherr Knigge who wrote the book Über den Umgang mit Menschen (On Human Relations) in the late 18th century. However, this book is about good manners and also about the social state of its time, but not about etiquette.

Etiquette may be wielded as a social weapon. The outward adoption of the superficial mannerisms of an in-group, in the interests of social advancement rather than a concern for others, is considered by many a form of snobbery, lacking in virtue.

See also

|

Etiquette and language |

Etiquette and society

|

Worldwide etiquette |

References

- ↑ Wright & Evans, Historical and Descriptive Account of the Caricatures of James Gillray (1851, OCLC 59510372), p. 473

- ↑ OED, "Etiquette".

- ↑ "Louis XIV". History.com. Retrieved December 13, 2012.

- ↑ "The Third Earl of Shaftesbury and the Progress of Politeness". Retrieved 2012-12-17.

- ↑ "Information Britain". Retrieved 13 September 2014.

- ↑ Cowan, 2005. p 101

- ↑ Mackie, 1998. p 1

- ↑ Henry Hitchings (2013). Sorry! The English and Their Manners. Hachette UK. Retrieved 2013-02-07.

- ↑ Mayo, Christopher. "Letters To His Son". The Literary Encyclopedia. First published 25 February 2007 accessed 30 November 2011.

- ↑ "Tudor Rose" (1999–2010). "Victorian Society". AboutBritain.com. Retrieved August 9, 2010.

- ↑ Richerson and Boyd, "The Evolution of Human Ultra Sociality", In press: I. Eibl-Eibisfeldt and F. Salter, eds. Ideology, Warfare, and Indoctrinability, 1997

- ↑ Norbert Elias, "The Civilizing Process", Oxford Blackwell Publishers, 1994

- ↑ Petersen A., Lupton D., "The Healthy Citizen", in The New Public Health - Discourses, Knowledges, Strategies, London, SAGE, 1996

- ↑ Bourdieu P., "Outline of a Theory of Practice, Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 1977

- ↑ Jenkins R., "Pierre Bourdieu (Key Sociologists), Cornwall, Routledge, 2002

- ↑ Douglas M., "Purity and Danger - An Analysis of Concepts of Pollution and Taboo London, Routledge, 2003

- ↑ Darwin C., The Expression of the Emotions in Man and Animals London, Penguin, 2009

- ↑ Curtis V.,Don’t Look, Don't Touch - The Science Behind Revulsion Oxford, Oxford University Press, 2013

Curtis V.Aunger R, Rabie T.,"Evidence that disgust evolved to protect from risk of disease Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 271 Suppl:S131–3., 2004 - 1 2 Neuberg SL., Cottrell CA.,"Evolutionary Bases of Prejudices" in Schaller M. et al., ed. Evolution and Social Psychology. New York, Psychology Press, 2006

- 1 2 Curtis V.,"Don’t Look, Don't Touch - The Science Behind Revulsion" Oxford, Oxford University Press, 2013

- ↑ Henrich J, Boyd R., "The Evolution of Conformist Transmission and the Emergence of Between Group Differences"Evolution and Human Behavior, 19(4):215–241, 1998

- ↑ Rotterdam, E. of. (1536). A Handbook on Good Manners for Children: De Civilitate Morum Puerilium Libellus. (E. Merchant, Ed.) (English tr.). London: Preface Publishing.

- ↑ Post, P., Post, A., Post, L., & Senning, D. P. (2011). Emily Post’s Etiquette, 18th Edition (Emily Post's Etiquette). New York: William Morrow.

- ↑ Vanderbilt, A. (1957). Amy Vanderbilt’s Complete Book Of Etiquette. New York: Doubleday & Company.

- ↑ Hartley, Florence (1860). "The Ladies' Book of Etiquette, and Manual of Politeness: A Complete Hand Book for the Use of the Lady in Polite Society". Boston: G. W. Cottrell.

- ↑ Martin, J. (1979). Miss Manners’ Guide to Excruciatingly Correct Behavior. New York: W. W. Norton & Company.

- ↑ Toksvig, S. (2013). Peas & Queues: The Minefield of Modern Manners. London: Profile Books Ltd.

- ↑ "Blue hair, body piercings--do employers care?". Grab Bag. Occupational Outlook Quarterly. 50 (3). Fall 2006. Retrieved August 9, 2010.

- ↑ Sherman, Joseph J (2015). "How they did it: Sharon Hill". FYI Magazine (August).

Sharon was a rising start at IBM. After a long span of promotions and top performance reviews, her career changed with one of IBM's Vice Presidents choose to cut the number of employees at the company. Sharon explains “My worldwide success, customer loyalty, and employee praise meant nothing. My department was cut and it was time to decide what I would do next in my life. That’s when I decided to follow my passion and start my own company. I got certified as an Etiquette trainer and was off and running. To this day, I thank IBM for teaching me professionalism and giving me the business acumen needed to start my business.”

- ↑ "Ho-Ching Wei". "Chinese-Style Conflict Resolution: A Case of Taiwanese Business Immigrants in Australia" (PDF). University of Western Sydney. Retrieved June 2, 2012.

- ↑ De Mente, Boyd (1994). Chinese Etiquette & Ethics in Business. Lincolnwood: NTC Business Books. ISBN 0-8442-8524-2.

- ↑ "Institute of Diplomacy and Business". Retrieved June 2, 2012.

- ↑ "IITTI website "About Us"". Retrieved 13 September 2014.

- ↑ Mitchell, Charles (1999). Short Course in International Business Culture. San Rafael: World Trade Press. ISBN 1-885073-54-2.

Further reading

- Baldrige, Letitia (2003). New Manners for New Times: A Complete Guide to Etiquette. New York: Scribner. p. 709. ISBN 0-7432-1062-X.

- Brown, Robert E.; Dorothea Johnson (2004). The Power of Handshaking for Peak Performance Worldwide. Herndon, Virginia: Capital Books, Inc. p. 98. ISBN 1-931868-88-3.

- Bryant, Jo (2008). Debrett's A–Z of Modern Manners. Debrett's Ltd. ISBN 1-870520-75-0.

- Debrett's Correct Form. Debrett's Ltd. 2006. ISBN 1-870520-88-2.

- From Clueless to Class Act: Manners for the Modern Woman. Sterling. 2006. ISBN 9781402739767.

- From Clueless to Class Act: Manners for the Modern Man. Sterling. 2006. ISBN 9781402739750.

- Farley, Thomas P. (September 2005). Town & Country Modern Manners: The Thinking Person's Guide to Social Graces. Hearst Books. p. 256. ISBN 1-58816-454-3.

- Grace, Elaine (2010). The Must-Have Guide to Posh Nosh Table Manners (EBook). The Britiquette Series. p. 66.

- Grace, Elaine (2007). The Slightly Rude But Much Needed Guide to Social Grace & Good Manners (EBook). The Britiquette Series. p. 101.

- Smith, Jodi R. (2011). The Etiquette Book: A Complete Guide to Modern Manners. Sterling. ISBN 9781402776021. - deal with proper etiquette for men and women.

- Johnson, Dorothea (1997). The Little Book of Etiquette. The Protocol School of Washington. Philadelphia: Running Press. p. 127. ISBN 978-0-7624-0009-6.

- Loewen, Arley (2003). "Proper Conduct (Adab) Is Everything: The Futuwwat-namah-I Sultani of Husayn Vaiz-I Kashifi". International Society for Iranian Studies: 544–570. JSTOR

- Tyler, Kelly A. (2008). Secrets of Seasoned Professionals: They learned the hard way so you don't have to. Fired Up Publishing. p. 146. ISBN 978-0-9818298-0-7.

- Martin, Judith (2005). Miss Manners' Guide to Excruciatingly Correct Behavior, Freshly Updated. W.W. Norton & Co. p. 858. ISBN 0-393-05874-3.

- Ramsey, Lydia (2007). Manners That Sell: Adding the Polish that Builds Profits. Longfellow Press. p. 188. ISBN 978-0967001203.

- Marsh, Peter (1988). Eye to Eye. Tospfield: Salem House Publishers. ISBN 0-88162-371-7.

- Smith, Deborah (2009). Socially Smart in 60 Seconds: Etiquette Do's and Don'ts for Personal and Professional Success. Peguesuse Publishers. ISBN 978-0-7369-2050-6.

- Business Class: Etiquette Essentials for Success at Work. St. Martin's Press. 2005. p. 198. ISBN 0-312-33809-0.

- Qamar-ul Huda (2004). "The Light Beyond Shore In the Theology of Proper Sufi Moral Conduct (Adab)". Journal of the American Academy of Religion. 72 (2): 461–484. doi:10.1093/jaar/72.2.461.

- Serres, Jean (2010) [1947]. Practical Handbook of Protocol. 3 avenue Pasteur – 92400 Courbevoie, France: Editions de la Bièvre. p. 474. ISBN 290595504X.

- Serres, Jean (2010) [1947]. "Manuel Pratique de Protocole", XIe Edition. 3 avenue Pasteur – 92400 Courbevoie, France: Editions de la Bièvre. p. 478. ISBN 2-905955-03-1.

- Tuckerman, Nancy (1995) [1952]. The Amy Vanderbilt Complete Book of Etiquette. Garden City: Doubleday. ISBN 0-385-41342-4. and Emily Post's book Etiquette in Society in Business in Politics and at Home were the U.S. etiquette bibles of the 1950s–1970s era.

External links

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Etiquette |

| Look up etiquette in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

- Etiquette in Society, in Business, in Politics and at Home, by Emily Post (1922)

- Modern Etiquette

- Debrett's

- House of Protocol

- World Business Etiquette Guides

- Royal Etiquette

- Email Etiquette