Marañón River

| Marañón River | |

| |

| Countries | Ecuador, Peru |

|---|---|

| Source | Andes |

| Mouth | Amazon River |

| Length | 1,737 km (1,079 mi) |

| Basin | 358,000 km2 (138,225 sq mi) |

| Discharge | |

| - average | 16,708 m3/s (590,037 cu ft/s) |

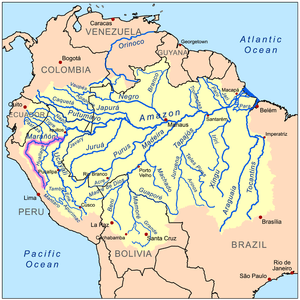

Map of the Amazon Basin with the Marañón River highlighted | |

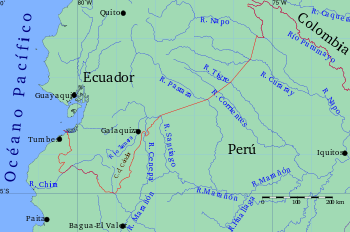

The Marañón River (Spanish: Río Marañón, IPA: [ˈri.o maɾaˈɲon]) is the principal or mainstem source of the Amazon River, arising about 160 km to the northeast of Lima, Peru, and flowing through a deeply eroded Andean valley in a northwesterly direction, along the eastern base of the Cordillera of the Andes, as far as 5 degrees 36' southern latitude; from where it makes a great bend to the northeast, and cuts through the jungle Andes, until at the Pongo de Manseriche it flows into the flat Amazon basin. Although historically, the term "Marañon River" often was applied to the river all the way to the Atlantic Ocean, nowadays the Marañon River is generally thought to end at the confluence with the Ucayali River, after which most cartographers label the ensuing waterway the Amazon River.

Geography

The Marañón River is Peru's second longest river according to a 2005 statistical publication by the Instituto Nacional de Estadística e Informática.[1]:21, pdf 13

Source of the Amazon

The Marañon River was considered the source of the Amazon River starting with the 1707 map published by Padre Samuel Fritz,[2]:58 who indicated the great river “has its source on the southern shore of a lake that is called Lauricocha, near Huánuco." Fritz’ reasoning was based on the fact that the Marañon River is the largest river branch one encounters when journeying upstream, something clearly evident on his map. For most of the 18th–19th centuries and into the 20th century, the Marañon River was generally considered the source of the Amazon. The Marañon River continues to claim the title of the "mainstem source" or "hydrological source" of the Amazon due to its contribution of the highest annual discharge rates, a distinction similar to the Mississippi's "source" at/near Lake Itasca in Minnesota and the Nile's "source" at/near Lake Tana on the Blue Nile in Ethiopia.

Description

On topographic maps, the Marañon River nominally begins by the town Rondos at the junction of the Lawriqucha and the Nupe Rivers, but its true source lies up one of these branches. The Lawriqucha River is the longer of the two, and emerges from a series of lakes, starting at lake Niño Qucha (Niño Cocha) and ending at lake Lawriqucha. The Nupe River emerges from lake Qarwaqucha near Mt. Yerupaja. Downstream of Rondos, the Marañon River flows as a small stream until other tributaries join it, the most important being the Urqumayu (Vizcarra), Puchka, Yanamayu, Crisnejas, Silaco and Chamaya. These together make the Marañon a major river with higher average flow than the Colorado River through Grand Canyon.

Just before entering the jungle, the Utcubamba and Chinchipe Rivers join the Marañon, usually more than doubling the flow. In the Andean jungle area, additional major tributaries join, including the Chiriaco, Cenepa, Nieva, and Santiago Rivers. This is an area inhabited by the Aguaruna people. After leaving the Andes, the Marañon is joined by additional major tributaries, including the Morona, Pastaza, Huallaga, Pacaya-Samiria, and Tigre Rivers. By the time it reaches the gauging station of San Regis before the Ucayali confluence, the Marañon has nearly the same average discharge rate as the Mississippi River at its mouth.

The initial section of the Marañon contains a plethora of pongos, which are gorges in the jungle areas often with difficult rapids. The Pongo de Manseriche is the final pongo on the Marañon located just before the river enters the flat Amazon basin. It is 5 km (3.1 mi) long and located between the confluence with the Rio Santiago, and the village of Borja. According to Captain Carbajal, who attempted ascent through the Pongo de Manseriche in the little steamer "Napo," in 1868, it is a vast rent in the Andes about 600 m (2000 ft) deep, narrowing in places to a width of only 30 m (100 ft), the precipices "seeming to close in at the top." Through this canyon the Marañón leaps along, at times, at the rate of 20 km/h (12 miles an hour). The pongo is known for wrecking many ships and many drownings.

Downstream of the Pongo de Manseriche the river often has islands, and there is usually nothing visible from its low banks but an immense forest-covered plain known as the selva baja ("low jungle") or Peruvian Amazonia. It is home to indigenous peoples such as the Urarina of the Chambira Basin , the Candoshi, and the Cocama-Cocamilla peoples.

A 552 km (343 mile) section of the Marañon River between Puente Copuma (Puchka confluence) and Corral Quemado is a class IV raftable river that is similar in many ways to the Grand Canyon of the United States and has been labeled the "Grand Canyon of the Amazon". Most of this section of the river is in a canyon that is up to 3000 m deep on both sides – over twice the depth of the Colorado's Grand Canyon. It is in dry desert-like terrain, much of which receives only 250–350 mm/rain per year (10–14"/year) with parts such as from Balsas to Jaén known as the hottest "infierno" area of Peru. The Marañon Grand Canyon section flows by the village of Calemar, where Peruvian writer Ciro Alegría based one of his most important novels: La serpiente de oro (1935).

Historical journeys

La Condamine, 1743

One of the first popular descents of the Marañon River occurred In 1743 the Frenchman Charles Marie de La Condamine, who journeyed from the Chinchipe confluence all the way to the Atlantic Ocean. La Condamine did not descend the initial section of the Marañon by boat due to the plethora of pongos. From where he began his boating descent at the Chiriaco confluence, La Condamine still had to confront several pongos, including the Pongo de Huaracayo (or Guaracayo) and the Pongo de Manseriche.

The Grand Canyon of the Amazon

The upper Marañon River has seen a number of descents. An attempt to paddle the river was made by Herbert Rittlinger in 1936. Sebastian Snow was an adventurer who journeyed down most of the river by trekking to Chiriaco River starting at the source near Lake Niñacocha.[3]

In 1976 and/or 1977 Laszlo Berty descended the section from Chagual to the jungle in raft.[4] In 1977, a group composed of Tom Fisher, Steve Gaskill, Ellen Toll, and John Wasson spent over a month descending the river from Rondos to Nazareth with kayaks and a raft.[5] In 2004, Tim Biggs and companions kayaked the entire river from the Nupe River to Iquitos.[6] In 2012, Rocky Contos descended the entire river with various companions along the way.[7]

Archaeology

The Chachapoya culture flourished in the basin of Maranon River. Gran Pajatén is an archaeological site of the Chachapoya located in the Andean cloud forests of Peru between the Marañon and Huallaga rivers. It is on the border of the La Libertad region and the San Martín region, and it was active in 200 BC. Los Pinchudos is an elaborate Chachapoya tomb complex.

The Recuay culture was a highland culture of Peru along the river from 200 BC-600 AD.

Chavín de Huantar was an ancient city located at the headwaters of the Marañón River.

Santa Ana (La Florida) is an important archaeological site in Ecuador, going back as early as 3,500 BC. It is located on the small Palanda River that flows into Mayo-Chinchipe river, and eventually into the Rio Marañon.

Hydroelectric dams

The Marañon River is endangered with 20 hydroelectric mega-dams planned in the Andes, and it has been speculated that most of the power is destined for export to Brazil, Chile or Ecuador.[8] Dam survey crews have drafted construction blueprints and the Environmental Impact Statements have been available since November 2009 for the Veracruz dam[9] and since November 2011 the Chadin2 dam.[10][11] A 2011 law stated "national demand" for the hydroelectric energy, while in 2013 Peruvian president Ollanta Humala explicitly made a connection with mining; the energy is to supply mines in the Cajamarca Region, La Libertad, Ancash Region and Piura Region.[12]

Concerns

Opposition arose because the dams are expected to disrupt the major source of the Amazon, alter normal silt deposition into the lower river, destroy habitat and migration patterns for fish and other aquatic life, displace thousands of residents along the river, and destroy a national treasure "at least as nice as the Grand Canyon in the USA". Residents have launched efforts to halt the dams along the river with conservation groups such as SierraRios[13][14] and International Rivers.[15]

Potential ecological impacts of 151 new dams greater than 2 MW on five of the six major Andean tributaries of the Amazon over the next 20 years are estimated to be high, including the first major break in connectivity between Andean headwaters and lowland Amazon and deforestation due to infrastructure.[16]

See also

- Extinct languages of the Marañón River basin

- List of rivers of Peru

- Loreto Region

- Maina Indians

- World Commission on Dams

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Marañón River. |

References

- ↑ Sistema Estadístico Nacional (2005). "Teritorio 1.8 Longitud aproximada de los rios mas importantes". Perú: Compendio Estadístico 2005 (PDF). Instituto Nacional de Estadística e Informática (INEI). p. 997.

- ↑ Samuel Fritz, George Edmundson (1922). Journal of the travels and labours of Father Samuel Fritz in ... Fritz, Samuel, 1654-1724. London, Printed for the Hakluyt Society.

- ↑ Sebastian Snow. My Amazon Adventure. Readers Book Club. ASIN B003Z01196. Retrieved 22 February 2013.

- ↑ "Laszlo Berty: rafting pioneer in Peru". SierraRios. n.d. Retrieved 22 February 2013.

- ↑ "First Descent of Río Marañon: Fisher, Gaskill, Toll, and Wasson Expedition". SierraRios. Retrieved 22 February 2013.

- ↑ Tim Biggs. Three Rivers of the Amazon. Amazon. ASIN B00507FRT2. Retrieved 10 February 2013.

- ↑ "First Descent of the Amazon Expedition". Sierra Rios. Retrieved 22 February 2013.

- ↑ "Peru's Energy Ambitions". The Economist. 12 February 2011. Retrieved 22 February 2013.

- ↑ "Proyecto Central Hidroeléctrica Veracruz 730 MW" (in Spanish). Sector Electricidad. 23 August 2012. Retrieved 22 February 2013.

- ↑ AC Energia S.A. (November 2011). "EIA Proyecto CH Chadín" (PDF). Ministerio de Energía y Minas. p. 59. Retrieved 5 May 2016.

- ↑ "EIS Chadin2 Dam". Estudio de Impacto Ambiental del Proyecto Hydroelectrica Chadin 2, AC Energia S.A. SierraRios. November 2011. p. 30. Retrieved 22 February 2013.

- ↑ Mongabay.org’s Special Reporting Initiatives (26 May 2015). "Peru planning to dam Amazon's main source and displace 1000s". The Guardian. Retrieved 5 May 2016.

- ↑ "Save Río Marañon". sierrarios.org. n.d. Retrieved 22 February 2013.

- ↑ "Graves impactos de la represa Chadín 2" (PDF). Infographic. Forum Solidaridad Peru. 23 September 2013. Retrieved 5 May 2016.

- ↑ "Río Marañon". International Rivers. n.d. Retrieved 22 February 2013.

- ↑ Finer M, Jenkins CN (2012). "Proliferation of Hydroelectric Dams in the Andean Amazon and Implications for Andes-Amazon Connectivity.". PLoS ONE. 7 (4): e35126. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0035126.

![]() This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "article name needed". Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "article name needed". Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

Coordinates: 7°58′03″S 77°17′52″W / 7.967438°S 77.297745°W