Wola Ostrowiecka massacre

| Massacre of Wola Ostrowiecka | |

|---|---|

|

| |

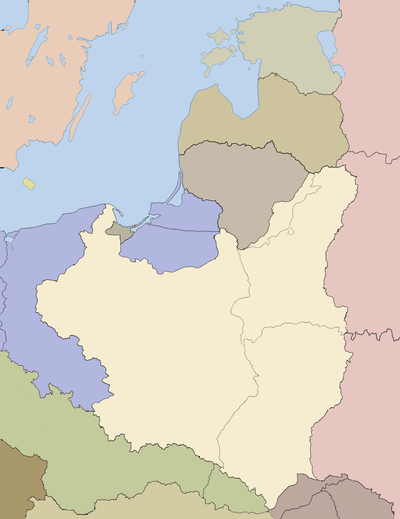

| Location | Wola Ostrowiecka, Volhynian Voivodeship, occupied Poland |

| Coordinates | 51°17′50″N 23°55′2″E / 51.29722°N 23.91722°ECoordinates: 51°17′50″N 23°55′2″E / 51.29722°N 23.91722°E |

| Date | 1943 |

| Target | Poles |

Attack type | Shooting and stabbing |

| Weapons | Axes, bludgeons |

| Deaths | 529 |

| Perpetrators | Ukrainian Insurgent Army |

Massacre of Wola Ostrowiecka was a 1943 mass murder of Polish inhabitants of the village of Wola Ostrowiecka located in the prewar gmina Huszcza in Luboml County (powiat lubomelski) of the Volhynian Voivodeship,[1] within the Second Polish Republic. Wola Ostrowiecka no longer exists.[2] It was burned to the ground during the Massacres of Poles in Volhynia and Eastern Galicia.[1]

The perpetrators were nationalists of the Ukrainian Insurgent Army's territorial command Piwnicz, aided by local Ukrainian peasants. On 30 August 1943, the Ukrainians surrounded the village, and began murdering the Polish inhabitants. Altogether, 79 families were murdered in their entirety, and in another 37 families, only one family member survived.[3] It has been estimated that 529 persons were murdered on that day, including at least 220 children under the age of 14.[4] Polish sociologist and researcher Tadeusz Piotrowski puts the number of murdered Poles at 529,[5] out of total village's population of 870. On the same day, Ukrainian nationalists murdered 438 Poles in the neighboring village of Ostrowki (see Massacre of Ostrowki).

Account of the massacre

According to the Polish survivors, the perpetrators had been preparing the attack for a few days in advance. The Poles noticed that their Ukrainian neighbors were drinking heavily, and chanting anti-Polish slogans.[6] On the morning of 29 August, the Ukrainians surrounded the village. At first, they acted in a friendly way, talking to children, and asking men to gather in a square in front of the school. A Ukrainian Insurgent Army officer made a speech, in which he urged Poles to fight the Germans, alongside the Ukrainians. At the same time, on the outskirts of the village, pits for dead bodies had already been dug. After the speech, all Polish men were asked to come for “physical examination” in a barn, one by one; they were killed by blows to the head with a blunt object.[6]

.jpg)

Once all the men had been killed, the women and children were locked in the school building. One of the survivors, a young girl named Marianna Soroka, later recounted that they began singing hymns, and their mother told them to prepare for death. Another survivor, Henryk Kloc, who was 13, stated that the Ukrainians set fire to the school, and then began firing at it and throwing grenades inside. Kloc, heavily wounded, lay among the dying in a school orchard, and watched the murderers kill the five-year-old son of Maria Jesionek. The boy's mother had already been killed, and her son was sitting next to her, asking her to go home. “Suddenly an armed Ukrainian came to him, and shot the boy in the head”. Kloc himself only survived because he played dead.[6] As soon as the massacre ended, local Ukrainian peasants began looting the village. After the massacre, the commander of the Ukrainian Insurgent Army's unit reported: “On August 29, I carried out the action in villages of Wola Ostrowiecka and Ostrówki. I liquidated all Poles, from the youngest to the oldest ones. I burnt all buildings, and appropriated all goods.”[8]

Archaeological studies

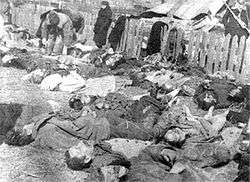

.jpg)

Between 17–22 August 1992, Polish scientists carried out exhumation in the area where the village once stood. During the exhumation, it was established that in most cases, the murderers used of the head of an axe or a bludgeon.[9] Wola Ostrowiecka no longer exists. Local Ukrainians call the village the Field of Dead Bodies. Every year, Polish survivors and their families organise a pilgrimage. In 2003, the village was going to be the center of celebrations of the 60th anniversary of the Massacres of Poles in Volhynia. However, at the last moment, plans were changed, and presidents Aleksander Kwasniewski, and Leonid Kuchma went to Poryck instead.[2]

Notes

- 1 2 Wołyń naszych przodków (2016). "Map of Powiat lubomelski showing dozens of locations of massacres of Poles". NaWolyniu.pl.

- 1 2 60th anniversary of the Massacres of Poles in Volhynia, kronikatygodnia.pl; accessed 6 December 2014.

- ↑ Tadeusz Piotrowski, Genocide and Rescue in Wolyn, page 81. McFarland, 2008; ISBN 0786407735.

- ↑ Info re Ukrainian massacres of Poles, deeppoliticsforum.com; accessed 8 December 2014.

- ↑ Tadeusz Piotrowski, Poland's Holocaust, p. 247. McFarland, 2008; ISBN 0786407735.

- 1 2 3 Genocide of Poles in Kresy; Wola Ostrowiecka i Ostrówki (31 August 1943), web.archive.orgl accessed 6 September 2014.

- ↑ Krzysztof Ogiolda with Dr Popek, "Ostrówki: Zbrodnia i pojednanie", Nowa Trybuna Opolska, NTO.pl, 26 November 2011; retrieved 19 June 2013.

- ↑ Władysław Filar, Wolyn 1939–1944, Toruń (2003), pp. 99–100; ISBN 8373226214

- ↑ Atrocities Committed in the Voivodship of Volhynia. ElectronicMuseum.ca via Internet Archive.

References

- Roman Mądro, Badania masowych grobów ludności polskiej zamordowanej przez nacjonalistów ukraińskich w roku 1943 w powiecie lubomelskim. Część I - Przebieg i wyniki ekshumacji w Woli Ostrowieckiej, (w:) Archiwum Medycyny Sądowej i Kryminologii, tom 43, nr 1, Kraków 1993, s. 47-63

- Wołyński testament (oprac.), Leon Popek, Tomasz Trusiuk, Paweł Wira, Zenon Wira, Lublin 1997, Towarzystwo Przyjaciół Krzemieńca i Ziemi Wołyńsko-Podolskiej; ISBN 83-908042-1-2;

- Exhumation of victims of the massacre. Kresy.pl

- Victims of the massacre. Kresy.pl

- Gallery, volhyniamassacre.eu; accessed 8 December 2014.