Mazatecan languages

| Mazatec | |

|---|---|

| En Ngixo | |

| Region | Mexico, states of Oaxaca, Puebla and Veracruz |

| Ethnicity | Mazatec |

Native speakers | 220,000 (2010 census)[1] |

|

Oto-Manguean

| |

| Official status | |

Official language in | In Mexico through the General Law of Linguistic Rights of Indigenous Peoples (in Spanish). |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-3 |

Variously: maa – Tecóatl maj – Jalapa maq – Chiquihuitlán mau – Huautla mzi – Ixcatlán vmp – Soyaltepec vmy – Ayautla vmz – Mazatlán |

| Glottolog |

maza1295[2] |

|

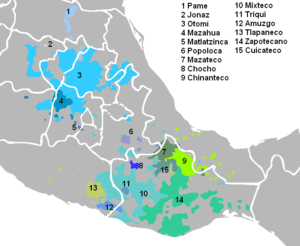

The Mazatecan language, number 7 (olive), center-east. | |

The Mazatecan languages are a group of closely related indigenous languages spoken by some 200,000 people in the area known as La Sierra Mazateca, which is located in the northern part of the state of Oaxaca in southern Mexico, as well as in adjacent areas of the states of Puebla and Veracruz.

The group is often described as a single language called Mazatec, but because several varieties are not mutually intelligible, they are better described as a group of languages.[3] The languages belong to the Popolocan subgroup of the Oto-Manguean language family. Under the "Law of Linguistic Rights" they are recognized as "national languages" along with the other indigenous languages of Mexico and Spanish.

The Mazatec language is vigorous in many of the smaller communities of the Mazatec area, and in many towns it is spoken by almost all inhabitants; however, the language is beginning to lose terrain to Spanish in some of the larger communities like Huautla de Jimenez and Jalapa de Díaz.

Like other Oto-Manguean languages, the Mazatecan languages are tonal, and tone plays an integral part in distinguishing both lexical items and grammatical categories. The centrality of tone to the Mazatec language is exploited by the system of whistle speech which is employed in most Mazatec communities and which allows speakers of the language to have entire conversations only by whistling.

Classification

The Mazatecan languages are part of the Oto-Manguean language family and belong to the family's Eastern branch. In that branch, they belong to the Popolocan subgroup together with the Popoloca, Ixcatec and Chocho languages. Brinton was the first to propose a classification of the Mazatec languages, which he correctly grouped with the Zapotec and Mixtec languages.[4] In 1892 he second-guessed his own previous classification and suggested that Mazatec was in fact related to Chiapanec-Mangue and Chibcha.[5]

Early comparative work by Morris Swadesh, Roberto Weitlaner and Stanley Newman laid the foundations for comparative Oto-Manguean studies, and Weitlaner's student María Teresa Fernandez de Miranda was the first to propose reconstruction of the Popolocan languages which while it cited Mazatec data, nonetheless left Mazatecan out of the reconstruction.[6]

Subsequent work by Summer Institute linguist Sarah Gudschinsky gave a full reconstruction first of Proto-Mazatec (Gudschinsky 1956) and then of Proto-Popolocan-Mazatecan (Gudschinsky 1959) (then referred to as Popotecan, a term which didn't catch on).

Languages

The ISO 639-3 standard enumerates eight Mazatecan languages. They are named after the villages they are spoken in:

- Chiquihuitlán Mazatec (2500 speakers in San Juan Chiquihuitlán. Quite divergent from other varieties.)

- Central

- Huautla Mazatec (50,000 speakers. The prestige variety of Mazatec, spoken in Huautla de Jimenez).

- Ayautla Mazatec (3500 speakers in San Bartolome Ayautla. Quite similar to Huautla.)

- Mazatlán Mazatec (13,000 speakers in Mazatlán and surrounding villages. Somewhat similar to Huautla.)

- Eloxochitlán Mazatec (aka or Jeronimo Mazatec (34,000 speakers in San Jerónimo Tecóatl, San Lucas Zoquiapan, Santa Cruz Acatepec, San Antonio Eloxochitlán and many other villages. Somewhat similar to Huautla.)

- Ixcatlán Mazatec (11,000 speakers in San Pedro Ixcatlan, Chichicazapa, and Nuevo Ixcatlan. Somewhat similar to Huautla.)

- Jalapa Mazatec (16,000 speakers in San Felipe Jalapa de Díaz. Somewhat similar to Huautla.)

- Soyaltepec Mazatec (23,000 speakers in San Maria Jacaltepec and San Miguel Soyaltepec. Somewhat similar to Huautla.)

Studies of mutual intelligibility between Mazatec-speaking communities revealed that most are relatively close but distinct enough that literacy programs must recognize local standards. The Huautla, Ayautla, and Mazatlán varieties are about 80% mutually intelligible; Tecóatl (Eloxochitlán), Jalapa, Ixcatlán, and Soyaltepec are more distant, at 70%+ intelligibility with Hautla or with each other. Chiquihuitlán is divergent.[7]

In 2005 there were 200,000 speakers of Mazatecan languages according to INEGI. Approximately 80% of these speakers know and use Spanish for some purposes. However, many Mazatec children know little or no Spanish when they enter school.

Dialect history

The language is divided into many dialects, or varieties, some of which are not mutually intelligible. The western dialects spoken in Huautla de Jimenez, and San Mateo Huautla, Santa Maria Jiotes, Eloxochitlán, Tecóatl, Ayautla, and Coatzospan are often referred to as Highland Mazatec, whereas the North Eastern dialects spoken in San Miguel Huautla, Jalapa de Díaz, Mazatlán de Flores, San Pedro Ixcatlán and San Miguel Soyaltepec are referred to as Lowland Mazatec. The Highland and Lowland dialects differ by a number of sound changes shared by each of the groups, particularly sound changes affecting the proto-Mazatecan phoneme /*tʲ/.

The San Miguel Huautla dialect occupies an intermediary position sharing traits with both groups.[3] The division between highland and lowland dialects corresponds to the political division between highland and lowland territories which existed in the period between CE 1300 and 1519. During the period of Aztec dominance from 1456 to 1519, the Highland territory was ruled from Teotitlán del Camino and the lowland territory from Tuxtepec, and this division continues to this day.[3]

The distinction between highland and lowland dialects is supported by shared sound changes: in Lowland Mazatec dialects, proto-Mazatecan /*tʲ/ merged with /*t/ before front vowels /*i/ and /*e/, whereas in the Highland dialects /*tʲ/ merged with /*ʃ/ in position before /*k/.[3]

Lowland dialects

Lowland dialects then split into Valley dialects and the dialect of San Miguel Huautla – the dialect of San Miguel Huautla underwent the same sound change of /*tʲ/ to /ʃ/ before /*k/ which had already happened in the highland dialects, but it can be seen that in San Miguel Huautla this change happened after the merger of /*tʲ/ with /*t/ before /*i/ and /*e/. The Valley dialects underwent a change of /*n/ to /ɲ/ in sequences with a /vowel-hn-a/ or /vowel-hn-u/.[3]

The Valley dialects then separated into Southern (Mazatlán and Jalapa) and Northern (Soyaltepec and Ixcatlán) valley dialects. The Southern dialects changed /*tʲ/ to /t/ before /*k/ (later changing *tk to /hk/ in Mazatlán and simplifying to /k/ in Jalapa), whereas the Northern dialects changed /t͡ʃ/ to /t͡ʂ/ before /*/a. The dialect of Ixcatlán then separated from the one of Soyaltepec by changing sequences of /*tʲk/ and /*tk/ to /tik/ and /tuk/, respectively.[3]

Highland dialects

The Highland dialects split into Western and Eastern (Huautla de Jimenez and Jiotes) groups; in the Western dialects the sequence /*ʃk/ changed to /sk/ whereas the Eastern ones changed it to /hk/. The dialect of Huautla de Jimenez then changed sequences of /*tʲh/ to *ʃ before short vowels, whereas the dialect of Santa Maria Jiotes merged the labialized velar stop kʷ to k.[3]

| Mazatec |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |

Phonology

Like many other Oto-Manguean languages, Mazatecan languages have complex phonologies characterized by complex tone systems and several uncommon phonation phenomena such as creaky voice, breathy voice and ballistic syllables. The following review of a Mazatecan phoneme inventory will be based on the description of the Jalapa de Díaz variety published by Silverman, Blankenship et al. (1995).

Comparative Mazatec phonology

The Mazatecan variety with the most thoroughly described phonology is that of Jalapa de Díaz which has been described in two publications by Silverman, Blankenship, Kirk and Ladefoged (1994 and 1995). This description is based on acoustic analysis and contemporary forms of phonological analysis. To give an overview of the phonological variety among Mazatecan languages, it is presented here and compared to the earlier description of Chiquihuitlán Mazatec published by the SIL linguist A. R. Jamieson, in 1977. This description is not based on modern acoustic analysis and relies on a much more dated phonological theory, so it should be regarded as a tentative account. One fundamental distinction between the analyses is that where Silverman et al. analyze distinctions between aspirated and nasalized consonants, Jamieson analyzes these as sequences of two or more phonemes, arriving therefore at a much smaller number of consonants.

Vowels

There is considerable differences in the number of vowels in different Mazatec varieties. Huautla de Jímenez Mazatec has only four contrasting vowel qualities /i e a o/, whereas Chiquihuitlán has six.[8]

Jalapa Mazatec has a basic five vowel system contrasting back and front vowels and closed and open vowel height, with an additional mid high back vowel [o]. Additional vowels distinguish, oral, nasal, breathy and creaky phonation types. There is some evidence that there are also ballistic syllables contrasting with non-ballistic ones.

| Front | Back | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| oral | nasal | creaky | breathy | oral | nasal | creaky | breathy | |

| Close | [i] | [ĩ] | [ḭ] | [i̤] | [u] | [ũ] | [ṵ] | [ṳ] |

| Close-mid | [o] | [õ] | [o̰] | [o̤] | ||||

| Open | [æ] | [æ̃] | [æ̰] | [æ̤] | [ɑ] | [ɑ̃] | [ɑ̰] | [ɑ̤] |

Chiquihuitlán Mazatec on the other hand is described as having 6 vowels and a nasal distinction. Jamieson does not describe a creaky/breathy phonation distinction but instead describes vowels interrupted by glottal stop or aspiration corresponding to creakiness and breathiness respectively.[9]

| Front | Back | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| oral | nasal | interrupted by ʔ | interrupted by h | oral | nasal | interrupted by ʔ | interrupted by h | |

| Close | [i] | [ĩ] | [ḭ] | [i̤] | [u] | [ũ] | [ṵ] | [ṳ] |

| Close-mid | [e] | [ẽ] | [ḛ] | [e̤] | [o] | [õ] | [o̰] | [o̤] |

| Open | [æ] | [æ̃] | [æ̰] | [æ̤] | [ɑ] | [ɑ̃] | [ɑ̰] | [ɑ̤] |

Tone

Tone systems differ markedly between varieties. Jalapa Mazatec has three level tones (high, mid, low) and at least 6 contour tones (high-mid, low-mid, mid-low, mid-high, low-high, high-low-high).[10] Chiquihuitlán Mazatec has a more complex tone system with four level tones (high, midhigh, midlow, low) and 13 different contour tones (high-low, midhigh-low, midlow-low, high-high (longer than a single high), midhigh-high, midlow-high, low-high, high-high-low, midhigh-high-low, midlow-high-low, low-high-low, low-midhigh-low, low-midhigh).[9]

Mazatec of Huautla de Jimenez´ has distinctive tones on every syllable,[11] and the same seems to be the case in Chiquihuitlán. Mazatec only distinguishes tone on certain syllables.[9] But Huautla Mazatec has no system of tonal sandhi,[12] whereas the Soyaltepec[13] and Chiquihuitlán varieties have complex sandhi rules.[14][15]

Consonants

Jalapa Mazatec has a three-way contrast between aspirated/voiceless, voiced, and nasalized articulation for all plosives, nasals and approximants. The lateral [l] occurs only in loanwords, and the tap [ɾ] occurs in only one morpheme, the clitic ɾa "probably". The bilabial aspirated and plain stops are also marginal phonemes. [16]

| Bilabial | Dental | Postalveolar | Velar | Glottal | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Plosive | ||||||

| aspirated | (pʰ) | tʰ | kʰ | |||

| plain | (p) | t | k | ʔ | ||

| prenasalized | mb | nd | ŋɡ | |||

| Affricate | ||||||

| aspirated | tsʰ | tʃʰ | ||||

| unaspirated | ts | tʃ | ||||

| prenasalized | nd͡z | nd͡ʒ | ||||

| Fricative | ||||||

| voiceless | s | ʃ | h | |||

| Nasal | ||||||

| voiceless | m̥ | n̥ | ɲ̥ | |||

| plain | m | n | ɲ | |||

| modal (creaky) | m̰ | n̰ | ɲ̰ | |||

| Approximant | ||||||

| voiceless | ȷ̊ | ʍ | ||||

| plain | (l) | j | w | |||

| nasalized | j̃ | w̰ | ||||

| Tap | (ɾ) | |||||

Grammar

Verb morphology

In Chiquihutlán Mazatec, verb stems are of the shape CV (consonant+vowel) and are always inflected with a stem-forming prefix marking person and number of the subject and aspect. In addition, verbs always carry a suffix that marks the person and number of the subject. The vowel of this suffix fuses with the vowel of the verb stem.[17]

There are 18 verb classes distinguished by the shape of their stem-forming prefixes. Classes 1, 2, 7, 10 and 15 cover intransitive verbs, and the rest of the classes involve transitive verbs. Transitive verbs have two prefix forms, one used for third person and first person singular and another used for the other persons (2nd person plural and singular and first person plural inclusive and exclusive). Clusivity distinctions as well as the distinction between second and first person is marked by the tonal pattern across the word (morphemes and stem do not have inherent lexical tone).[17][18]

Person

Chiquihuitlán Mazatec distinguishes between three person categories (1st, 2nd, 3rd) and two numbers (singular, plural), and for the first person plural, it distinguishes between inclusive and exclusive categories. For third person, number is not specified, but only definiteness, distinguishing between third person definite and indefinite. For third person referents, number is only expressed by free pronouns or noun phrases when it is not directly retrievable from context.[17]

Tense and aspect

Chiquihuitlán Mazatec inflects for four aspects: completive, continuative, incompletive, as well as a neutral or unmarked aspect. Completive aspect is formed by prefixing /ka-/ to the neutral verb form, continuative is formed by prefixing /ti-/. The incompletive aspect has a distinct set of stem forming prefixes as well as distinct tone patterns. In incompletive transitive verbs, only the first person singular and third person prefixes vary from the corresponding neutral forms; the first person plural and second person forms are identical to the corresponding neutral one.[17]

Whistle speech

Most Mazatec communities employ forms of whistle speech, in which linguistic utterances are produced by whistling the tonal contours of words and phrases. Mazatec languages lend themselves very well to becoming whistling languages because of the high functional load of tone in Mazatec grammar and semantics. Whistling is extremely common among young men who often have complex conversations conducted entirely through whistling. Women on the other hand do not generally use whistle speech, just as older males use it more rarely than younger ones. Small boys learn to whistle simultaneously with learning to talk. Whistling is generally used for communicating over a distance, to attract the attention of passersby or to avoid interfering with ongoing spoken conversations, but even economic transactions can be conducted entirely through whistling. Since whistle speech does not encode information about vowel or consonants but only tone, it is often ambiguous with several possible meanings; however since most whistling treats a limited number of topics it is normally unproblematic to disambiguate meaning through context.[19]

Media

Mazatecan-language programming is carried by the CDI's radio station XEOJN, based in San Lucas Ojitlán, Oaxaca.

The entire New Testament is available in several varieties of Mazatec. The text can be found online in PDF or Audio at the Scripture Earth website owned by Wycliffe Canada. These were published by the Bible League.

A wide variety of Bible-based literature and video content is published in Mazatec by Jehovah's Witnesses.[20]

Notes

- ↑ INALI (2012) México: Lenguas indígenas nacionales

- ↑ Hammarström, Harald; Forkel, Robert; Haspelmath, Martin; Bank, Sebastian, eds. (2016). "Mazatecan". Glottolog 2.7. Jena: Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Gudschinsky 1958

- ↑ Brinton 1891

- ↑ Brinton 1892

- ↑ Fernandez de Miranda 1951

- ↑ Egland (1978).

- ↑ Suárez 1983:59

- 1 2 3 Jamieson 1977

- ↑ Silverman et al. 1995:72

- ↑ Suárez 1983:52

- ↑ K Pike 1948:95

- ↑ E. Pike 1956

- ↑ Jamieson 1977:113

- ↑ Suárez 1983:53

- ↑ Silverman et al. 1995:83

- 1 2 3 4 Léonard & Kihm 2010

- ↑ see also this short paper by Léonard & Kihm

- ↑ Cowan 1948

- ↑ "Bible literature in Mazatec". Watch Tower Bible and Tract Society.

References

- Agee, Daniel; Marlett, Stephen (1986). "Indirect Objects and Incorporation in Mazatec". Work Papers of the Summer Institute of Linguistics. 30: 59–76.

- Agee, Margaret (1993). "Fronting in San Jeronimo Mazatec" (PDF). SIL-Mexico Workpapers. 10: 29–37.

- Brinton, Daniel G. (1891). "The American Race: A Linguistic Classification and Ethnographic Description of the Native Tribes of North and South America". New York.

- Brinton, Daniel G. (1892). "On the Mazatec Language of Mexico and Its Affinities". Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society. American Philosophical Society. 30 (137): 31–39. JSTOR 983207.

- CDI (Comisión Nacional para el Desarrollo de los Pueblos Indígenas) (2004–2007). "Mazatecos – Ha shuta Enima". Información: Los pueblos indígenas de México (in Spanish). CDI. Archived from the original on 2007-06-09. Retrieved 2007-05-02.

- Cowan, George M. (1948). "Mazateco Whistle Speech". Language. Language, Vol. 24, No. 3. 24 (3): 280–286. doi:10.2307/410362. JSTOR 410362.

- Duke, Michael R. (n.d.). "Writing Mazateco: Linguistic Standardization and Social Power". Introduction to Linguistic Anthropology, Course Ant-392N. University of Texas at Austin. Retrieved 2008-02-29.

- Egland, Steven (1978). La inteligibilidad interdialectal en México: Resultados de algunos sondeos (PDF online facsimile of 1983 reprinting) (in Spanish). México, D.F.: Instituto Lingüístico de Verano. ISBN 968-31-0003-1. OCLC 29429401.

- Faudree, Paja (2006). Fiesta of the Spirits, Revisited: Indigenous Language Poetics and Politics among Mazatecs of Oaxaca, Mexico. University of Pennsylvania: Unpublished PhD. dissertation. ISBN 978-0-542-79891-7.

- Fernandez de Miranda; Maria Teresa (1951). "Reconstruccion del Protopopoloca". Revista Mexicana de Estudios Antropológicos. 12: 61–93.

- Golston,Chris; Kehrein, Wolfgang (1998). "Mazatec Onsets and Nuclei". IJAL. 64 (4): 311–337. doi:10.1086/466364.

- Gudschinsky, Sarah C. (1953). "Proto-Mazateco". Ciencias Sociales, Memoria del Congreso Científico Mexican. Mexico: Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México. 12: 171–74.

- Gudschinsky, Sarah C. (1956). Proto-Mazatec Structure. University of Pennsylvania: Unpublished MA thesis.

- Gudschinsky, Sarah C. (1958). "Native Reactions to Tones and Words in Mazatec". Word. 14: 338–45.

- Gudschinsky, Sarah C. (1958). "Mazatec Dialect History: A Study in Miniature". Language. 34 (4): 469–481. doi:10.2307/410694. JSTOR 410694.

- Gudschinsky, Sarah C. (1959). "Discourse Analysis of a Mazatec Text". IJAL. 25 (3): 139–146. doi:10.1086/464520. JSTOR 1263788.

- Gudschinsky, Sarah C. (1959). "Mazatec Kernel Constructions and Transformations". IJAL. 25 (2): 81–89. doi:10.1086/464507. JSTOR 1263623.

- Gudschinsky, Sarah C. (1951). "Solving the Mazateco Reading Problem". Language Learning. 4: 61–65. doi:10.1111/j.1467-1770.1951.tb01184.x.

- Gudschinsky, Sarah C. (1959). "Toneme Representation in Mazatec Orthography". Word. 15: 446–52.

- Jamieson, A. R. (1977a). "Chiquihuitlán Mazatec Phonology". In Merrifield, W. R. Studies in Otomanguean Phonology. Arlington, Texas: SIL-University of Texas. pp. 93–105.

- Jamieson, A. R. (1977b). "Chiquihuitlán Mazatec Tone". In Merrifield, W. R. Studies in Otomanguean Phonology. Arlington, Texas: SIL-University of Texas. pp. 107–136.

- Jamieson, C. A. (1982). "Conflated Subsystems Marking Person and Aspect in Chiquihuitlán Mazatec Verbs". IJAL. 48 (2): 139–167. doi:10.1086/465725.

- Jamieson, C. A.; Tejeda, E. (1978). "Mazateco de Chiquihuitlan, Oaxaca". Archives of the Indigenous Languages of Mexico (ALIM). México: CIIS.

- Jamieson, C. A. (1996). "Chiquihuitlán Mazatec Postverbs: The Role of Extension in Incorporation". In Casad, Eugene H. Cognitive Linguistics in the Redwoods: The Expansion of a New Paradigm in Linguistics. Volume 6 of Cognitive Linguistics Research. Walter de Gruyter.

- Kirk, Paul L. (1970). "Dialect Intelligibility Testing: The Mazatec Study". IJAL. The University of Chicago Press. 36 (3): 205–211. doi:10.1086/465112. JSTOR 1264590.

- Kirk, Paul L. (1985). "Proto-Mazatec Numerals". IJAL. The University of Chicago Press. 51 (4): 480–482. doi:10.1086/465940. JSTOR 1265311.

- Léonard, Jean-Leo; Kihm, Alain (2010). "Verb Inflection in Chiquihuitlán Mazatec: A Fragment and a PFM Approach". In Müller, Stefan. Proceedings of the HPSG10 Conference (PDF). Université Paris Diderot: CSLI Publications.

- Schane, S. A. (1985). "Vowel Changes of Mazatec". IJAL. 51 (4): 62–78. doi:10.1086/465979.

- Schram, J. L.; Pike, E. V. (1978). "Vowel Fusion in Mazatec of Jalapa de Días". IJAL. 44 (4): 257–261. doi:10.1086/465554.

- Schram, T. L. (1979). "Tense, Tense Embedding and Theme in Discourse in Mazatec of Jalapa de Díaz". In Jones, Linda K. Discourse Studies in Mesoamerican Languages: Discussion. Summer Institute of Linguistics and the University of Texas at Arlington.

- Schram, T. L.; Jones, Linda K. (1979). "Participant Reference in Narrative Discourse in Mazatec de Jalapa de Díaz". In Jones, Linda K. Discourse Studies in Mesoamerican Languages: Discussion (PDF). Summer Institute of Linguistics and the University of Texas at Arlington.

- Schram, T. L. (1979). "Theme in a Mazatec Story". In Jones, Linda K. Discourse Studies in Mesoamerican Languages: Discussion. Summer Institute of Linguistics and the University of Texas at Arlington.

- Pike, Eunice V. (1956). "Tonally Differentiated Allomorphs in Soyaltepec Mazatec". IJAL. The University of Chicago Press. 22 (1): 57–71. doi:10.1086/464348. JSTOR 1263579.

- Regino, Juan Gregorio; Hernández-Avila, Inés (2004). "A Conversation with Juan Gregorio Regino, Mazatec Poet: June 25, 1998". American Indian Quarterly. University of Nebraska Press. 28 (1/2, Special Issue: Empowerment Through Literature): 121–129. doi:10.1353/aiq.2005.0009. JSTOR 4139050.

- Silverman, Daniel; Blankenship, Barbara; Kirk, Paul; Ladefoged, Peter (1995). "Phonetic Structures in Jalapa Mazatec". Anthropological Linguistics. 37 (1): 70–88. JSTOR 30028043.

- Ventura Lucio, Felix (2006). "La situación sociolingüística de la lengua mazateca de Jalapa de Díaz en 2006" (PDF online publication). In Marlett, Stephen A. Situaciones sociolingüísticas de lenguas amerindias. Lima: SIL International and Universidad Ricardo Palma.

- Weitlaner, Roberto J.; Weitlaner, Irmgard (1946). "The Mazatec Calendar". American Antiquity. Society for American Archaeology. 11 (3): 194–197. doi:10.2307/275562. JSTOR 275562.