Mbuti people

Mbuti or Bambuti are one of several indigenous pygmy groups in the Congo region of Africa. Their languages are Central Sudanic languages (a family of the Nilo-Saharan phylum) and Bantu languages.

A group of Mbuti, with explorer Osa Johnson, in 1930 | |

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| (30,000-50,000?) | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| Democratic Republic of the Congo | |

| Languages | |

| Efe, Asoa, Kango | |

| Religion | |

| Bambuti mythology | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Pygmies (generally assumed) |

Overview

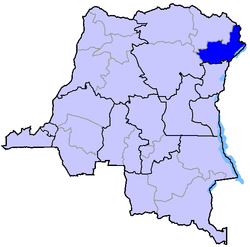

The Mbuti population lives in the Ituri Forest, a tropical rainforest covering about 70,000 km2 of the north/northeast portion of the Democratic Republic of the Congo. Bambuti are pygmy hunter-gatherers, and are one of the oldest indigenous people of the Congo region of Africa. The Bambuti are composed of bands which are relatively small in size, ranging from 15 to 60 people. The Bambuti population totals about 30,000 to 40,000 people. There are four distinct cultures within the Bambuti. These are

- The Efé, who speak the language of a neighboring Sudanic people, Lese.

- The Sua AKA Kango AKA Mbuti, who speak a dialect (or perhaps two) of the language of a neighboring Bantu people, Bila.

- The Asua, the only Mbuti people with their own language, which is closely related to that of the neighboring Sudanic Mangbetu.

The term BaMbuti (Mbuti) is therefore confusing, as it has been used to refer to all the pygmy peoples in the Ituri region in general, as well as to a single subgroup in the center of the Ituri forest.[1]

Around 2500 BCE, the Ancient Egyptians made reference to a "people of the trees" that could have been the Mbuti.

Environment

The forest of Ituri is a tropical rainforest. In this area, there is a high amount of rainfall annually, ranging from 50 to 70 inches[1] (127 cm to 178 cm). The rainforest covers 70,000 square kilometers.The Mbuti population lives in the Ituri Forest, a tropical rainforest covering about 70,000 km2 of the north/northeast portion of the Congo. The dry season is relatively short, ranging from one to two months in duration.[1] The forest is a moist, humid region strewn with rivers and lakes. Several ecological problems exist which affect the Bambuti. Disease is prevalent in the forests and can spread quickly, killing not only humans, but plants, and animals, the major source of food, as well. One disease, carried by tsetse flies, is sleeping sickness, which limits the use of large mammals.[2] Too much rainfall, as well as droughts, can greatly diminish the food supply.

Settlement architecture and organization

The Bambuti live in villages that are categorized as bands. Each hut houses a family unit. At the start of the dry season, they leave the village to enter the forest and set up a series of camps.[2] This way the Bambuti are able to utilize more land area for maximum foraging. These villages are solitary and separated from other groups of people. Their houses are small, circular, and very temporary.

House construction begins with the tracing of the outline of the house into the ground.[1] The walls of the structures are strong sticks that are placed in the ground, and at the top of the sticks, a vine is tied around them to keep them together.[1] Large leaves are used in the construction of the hut roofs.

Food and resources

The Bambuti are primarily hunter-gatherers. Their animal foodstuffs include crabs, shellfish, ants, larvae, snails, pigs, antelopes, monkeys, fish, and honey. The vegetable component of their diet includes wild yams, berries, fruits, roots, leaves, and kola nuts.[2]

While hunting, the Bambuti have been known to specifically target the giant forest hog. The meat obtained from the giant forest hog (as is the meat from rats) is often considered kweri, a bad animal which may cause illness to those who eat it, but is often valuable as a trade good between the Bambuti and agriculturalist Bantu groups. There is some lore that is thought to have identified giant forest hogs as kweri due to their nocturnal habits and penchant for disruption of the few agricultural advances the Bambuti have made. This lore can be tied to Bambuti mythology, where the giant forest hog is thought to be a physical manifestation of Negoogunogumbar. Further, there are unconfirmed reports of giant forest hogs eating Bambuti infants from their cribs in the night. Other food sources yielded by the forest are non-kweri animals for meat consumption, root plants, palm trees, and bananas;[2] and in some seasons, wild honey.[1] Yams, legumes, beans, peanuts, hibiscus, amaranth, and gourds are consumed.[2] The Bambuti use large nets, traps, and bows and arrows to hunt game. Women and children sometimes assist in the hunt by driving the prey into the nets. Both sexes gather and forage. Each band has its own hunting ground, although boundaries are hard to maintain.[1] The Mbuti call the forest "mother" and "father" as the mood seizes them, because, like their parents, the forest gives them food, shelter and clothing, which are readily made from abundant forest materials.[3]

Trade

The Bantu villagers produce many items that the hunter gatherers trade some of their products for. They often obtain iron goods, pots, wooden goods, and basketry, in exchange for meat, animal hides, and other forest goods.[1] Bushmeat is a particularly frequently traded item. They will also trade to obtain agricultural products from the villagers through barter.[1]

Labor

Hunting is usually done in groups, with men, women, and children all aiding in the process. Women and children are not involved if the hunting involves the use of a bow and arrow, but if nets are used, it is common for everyone to participate. In some instances women may hunt using a net more often than men. The women and the children herd the animals to the net, while the men guard the net. Everyone engages in foraging, and women and men both take care of the children. Women are in charge of cooking, cleaning and repairing the hut, and obtaining water. The kin-based units work together to provide food and care for the young. It is easier for men to lift the women up into the trees for honey.

Kinship and descent system

The Bambuti tend to follow a patrilineal descent system, and their residences after marriage are patrilocal. However, the system is rather loose. The only type of group seen amongst the Bambuti is the nuclear family.[1] Kinship also provides allies for each group of people.

Marriage customs

Sister exchange is the common form of marriage.[1] Based on reciprocal exchange, men from other bands exchange sisters or other females to whom they have ties.[1] In Bambuti society, bride wealth is not customary. There is no formal marriage ceremony: a couple are considered officially married when the groom presents his bride's parents with an antelope he alone has hunted and killed. Polygamy does occur, but at different rates depending on the group, and it is not very common. The sexual intercourse of married couples is regarded as an act entirely different from that of unmarried partners, for only in marriage may children be conceived.[4]

Political structure

Bambuti societies have no ruling group or lineage, no overlying political organization, and little social structure. The Bambuti are an egalitarian society in which the band is the highest form of social organization.[1] Leadership may be displayed for example on hunting treks.[1]Men become leaders because they are good hunters. Owing to their superior hunting ability, leaders eat more meat and fat and fewer carbohydrates than other men.[5] Men and women basically have equal power. Issues are discussed and decisions are made by consensus at fire camps; men and women engage in the conversations equivalently.[1] If there is a disagreement, misdemeanor, or offense, then the offender may be banished, beaten or scorned.(in more recent times the practice is to remove the offender from the forest and have them work for private landowners for little to no pay.[1]

Religion

- See Bambuti mythology.

Everything in the Bambuti life is centered on the forest. They consider the forest to be their great protector and provider and believe that it is a sacred place. They sometimes call the forest "mother" or "father". An important ritual that impacts the Bambuti's life is referred to as molimo. After events such as death of an important person in the tribe, molimo is noisily celebrated to wake the forest, in the belief that if bad things are happening to its children, it must be asleep.[1] As with many Bambuti rituals, the time it takes to complete a molimo is not rigidly set; instead, it is determined by the mood of the group. Food is collected from each hut to feed the molimo, and in the evening the ritual is accompanied by the men dancing and singing around the fire. Women and children must remain in their huts with the doors closed. These practices were studied thoroughly by British anthropologist Colin Turnbull, known primarily for his work with the tribe.

"Molimo" is also the name of a trumpet the men play during the ritual. Traditionally, it was made of wood or sometimes bamboo, but Turnbull also reported the use of metal drainpipes. The sound produced by a molimo is considered more important than the material it is made out of. When not in use, the trumpet is stored in the trees of the forest. During a celebration, the trumpet is retrieved by the youth of the village and carried back to the fire.[1]

Ota Benga controversy

Ota Benga (circa 1883[6] – March 20, 1916) was a Congolese Mbuti pygmy known for being featured with other Africans in an anthropology exhibit at the Louisiana Purchase Exposition in St. Louis, Missouri in 1904, and later in a controversial human zoo exhibit in the Bronx Zoo in 1906. Benga had been freed from slave traders in the Congo by the missionary Samuel Phillips Verner, who had taken him to Missouri. At the Bronx Zoo, Benga had free run of the grounds before and after he was "exhibited" in the zoo's Monkey House. Displays of non-Western humans as examples of "earlier stages" of human evolution were common in the early 20th century, when racial theories were frequently intertwined with concepts from evolutionary biology.

African-American newspapers around the nation carried editorials strongly opposing Benga's treatment. Dr. R.S. MacArthur, the spokesperson for a delegation of black churches, petitioned the New York City mayor for his release. The mayor released Benga to the custody of Reverend James M. Gordon, who supervised the Howard Colored Orphan Asylum in Brooklyn and made him a ward. That same year Gordon arranged for Benga to be cared for in Virginia, where he paid for him to acquire American clothes and to have his teeth capped, so the young man could be part of society. Benga was tutored in English and began to work. When, several years later, the outbreak of World War I stopped passenger travel on the oceans and prevented his returning to Africa, he became depressed. He committed suicide in 1916 at the age of 32.[7]

Major challenges today

The way of life of the Bambuti is threatened for various reasons. Their territory in the DRC has no legal protections, and the boundaries that each band claims are not formally established. Bambuti are no longer allowed to hunt large game. Due to deforestation, gold mining, and modern influences from plantations, agriculturalists, and efforts to conserve the forests, their food supply is threatened. There is also significant civil unrest in the country.

See also

Notes

5 ^ Ehret, Christopher (1998). The Civilizations of Africa. Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia.

7 ^ King, Glenn (2002). Traditional Cultures. Prospect Heights, Illinois: Waveland Press.

28 ^ Day, Thomas (2005). The Largest Expanse. Sydney, New South Wales (Australia): The Technics University Of Australia.

29 ^ Ichikawa, Mitsuo (1987). Food Restrictions of the Mbuti Pygmies. Kyoto University.

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 Mukenge, Tshilemalea (2002). Culture and Customs of the Congo. Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Press.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Turnbull, Colin M. (1968). The Forest People. New York, Simon and Schuster, Inc.

- ↑ Turnbull C. Processional Ritual among the Mbuti Pygmies // The Drama Review: TDR, Vol. 29, No. 3, Processional Performance (Autumn, 1985),p. 8

- ↑ Mosko M. The Symbols of "Forest": A Structural Analysis of Mbuti Culture and Social Organization // American Anthropologist, New Series, Vol. 89, No. 4 (Dec., 1987), p. 899

- ↑ Hewlett B., Walker P. Social Status and Dental Health among the Aka and Mbuti Pygmies // American Anthropologist, New Series, Vol. 93, No. 4 (Dec., 1991), p. 944

- ↑ Bradford and Blume (1992), p. 54.

- ↑ Evanzz, Karl (1999). The Messenger: The rise and fall of Elijah Muhammad. New York: Pantheon Books. ISBN 0-679-44260-X.

Further reading

- Hewlett B., Walker P. Social Status and Dental Health among the Aka and Mbuti Pygmies // American Anthropologist, New Series, Vol. 93, No. 4 (Dec., 1991), p. 943-944.

- Mosko M. The Symbols of "Forest": A Structural Analysis of Mbuti Culture and Social Organization // American Anthropologist, New Series, Vol. 89, No. 4 (Dec., 1987), p. 896-913.

- Turnbull C. Processional Ritual among the Mbuti Pygmies // The Drama Review: TDR, Vol. 29, No. 3, Processional Performance (Autumn, 1985), p. 6-17.

External links

- Todd Pitman, Mbuti Net Hunters of the Ituri Forest, story with photos and link to Audio Slideshow. The Associated Press, 2010.

- The Mbuti of Zaire, uconn.edu

- African Pygmies Hunter-Gatherers of Central Africa, with photos and soundscapes

- Stephanie McCrummen, "Lured Toward Modern Life, Pygmy Families Left in Limbo", The Washington Post, 12 November 2006

- 'Erasing the Board' Report of the international research mission into crimes under international law committed against the Bambuti Pygmies in the eastern Democratic Republic of Congo; Minority Rights Group International, July 2004

- http://foragers.wikidot.com/mbuti More information about the Mbuti on a site that is devoted to the scientific study of the diversity of forager societies without recreating a myth.

- http://turnbullandthembuti.pbwiki.com/ a critique of Colin Turnbull's The Forest People