Mesosome

Mesosomes are folded invaginations in the plasma membrane of bacteria that are produced by the chemical fixation techniques used to prepare samples for electron microscopy. Although several functions were proposed for these structures in the 1960s, they were recognized as artifacts by the late 1970s and are no longer considered to be part of the normal structure of bacterial cells. Mesosomes is the site of chromosomal attachment during cell division.

Function

Mesosomes, as seen with the electron micrograph, are folded membrane protrusions that may come in the form of lamellae, tubules or vesicles. These occur in some (not all) prokaryotes, such as cyanobacteria, nitrogen-fixing bacteria, and sporulating bacteria.

Because prokaryotes do not have membrane-bound organelles, the mesosome increases the surface area of the cell, aiding the cell in cellular respiration. This is analogous to cristae in the mitochondrion in eukaryotic cells, which are finger-like protrusions and help eukaryotic cells undergo cellular respiration.

There are two types of mesosomes, septal mesosomes which extend from the membrane towards the centre of the cytoplasm and are usually associated with nuclear material, and lateral mesosomes which are found at the periphery.

Mesosomes are also thought to aid in photosynthesis, cell division, DNA replication, cell compartmentalisation etc. They can be chemically induced in bacteria.

Initial observations

These structures are invaginations of the plasma membrane observed in gram-positive bacteria that have been chemically fixed to prepare them for electron microscopy.[2] They were first observed in 1953 by George B. Chapman and James Hillier,[3] who referred to them as "peripheral bodies." They were termed "mesosomes" by J. D. Robertson in 1959.[4] Initially, it was thought that mesosomes might play a role in several cellular processes, such as cell wall formation during cell division, chromosome replication, or as a site for oxidative phosphorylation.[5][6]

Disproof of hypothesis

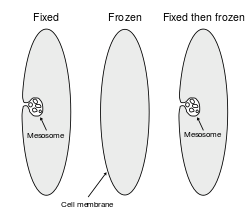

These models were called into question during the late 1970s when data accumulated suggesting that mesosomes are artifacts formed through damage to the membrane during the process of chemical fixation, and do not occur in cells that have not been chemically fixed.[2][7][8] By the mid to late 1980s, with advances in cryofixation and freeze substitution methods for electron microscopy, it was generally concluded that mesosomes do not exist in living cells.[9][10][11] However, a few researchers continue to argue that the evidence remains inconclusive, and that mesosomes might not be artifacts in all cases.[12][13]

Recently, similar folds in the membrane have been observed in bacteria that have been exposed to some classes of antibiotics,[14] and antibacterial peptides (defensins).[15] The appearance of these mesosome-like structures may be the result of these chemicals damaging the plasma membrane and/or cell wall.[16]

The case of the proposal and then disproof of the mesosome hypothesis has been discussed from the viewpoint of the philosophy of science as an example of how a scientific idea can be falsified and the hypothesis then rejected, and analyzed to explore how the scientific community carries out this testing process.[17][18][19]

See also

References

- ↑ Nanninga N (1971). "The mesosome of Bacillus subtilis as affected by chemical and physical fixation". J. Cell Biol. 48 (1): 219–24. doi:10.1083/jcb.48.1.219. PMC 2108225

. PMID 4993484.

. PMID 4993484. - 1 2 Silva MT, Sousa JC, Polónia JJ, Macedo MA, Parente AM (1976). "Bacterial mesosomes. Real structures or artifacts?". Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 443 (1): 92–105. doi:10.1016/0005-2736(76)90493-4. PMID 821538.

- ↑ Chapman, George B. & Hillier, James (1953). "Electron microscopy of ultra-thin sections of bacteria I. Cellular division in Bacillus cereus". J. Bacteriol.: 362–373.

- ↑ Robertson, J.D. (1959). "The ultra structure of cell membranes and their derivatives, Biochem". Soc. Syrup: 3.

- ↑ Suganuma A (1966). "Studies on the fine structure of Staphylococcus aureus". J Electron Microsc (Tokyo). 15 (4): 257–61. PMID 5984369.

- ↑ Pontefract RD, Bergeron G, Thatcher FS (1969). "Mesosomes in Escherichia coli". J. Bacteriol. 97 (1): 367–75. doi:10.1002/path.1710970223. PMC 249612

. PMID 4884819.

. PMID 4884819. - ↑ Ebersold HR, Cordier JL, Lüthy P (1981). "Bacterial mesosomes: method dependent artifacts". Arch. Microbiol. 130 (1): 19–22. doi:10.1007/BF00527066. PMID 6796029.

- ↑ Higgins ML, Tsien HC, Daneo-Moore L (1976). "Organization of mesosomes in fixed and unfixed cells". J. Bacteriol. 127 (3): 1519–23. PMC 232947

. PMID 821934.

. PMID 821934. - ↑ Ryter A (1988). "Contribution of new cryomethods to a better knowledge of bacterial anatomy". Ann. Inst. Pasteur Microbiol. 139 (1): 33–44. doi:10.1016/0769-2609(88)90095-6. PMID 3289587.

- ↑ Nanninga N, Brakenhoff GJ, Meijer M, Woldringh CL (1984). "Bacterial anatomy in retrospect and prospect". Antonie Van Leeuwenhoek. 50 (5-6): 433–60. doi:10.1007/BF02386219. PMID 6442119.

- ↑ Dubochet J, McDowall AW, Menge B, Schmid EN, Lickfeld KG (1 July 1983). "Electron microscopy of frozen-hydrated bacteria". J. Bacteriol. 155 (1): 381–90. PMC 217690

. PMID 6408064.

. PMID 6408064. - ↑ John F. Stolz (1991) "Structure of Phototrophic Prokaryotes" CRC Press ISBN 0-8493-4814-5

- ↑ Murata, K.; Kawai, S.; Mikami, B.; Hashimoto, W. (2008). "Superchannel of Bacteria: Biological Significance and New Horizons". Bioscience, Biotechnology, and Biochemistry. 72: 265–277. doi:10.1271/bbb.70635. PMID 18256495.

- ↑ Santhana Raj L, Hing HL, Baharudin O, et al. (2007). "Mesosomes are a definite event in antibiotic-treated Staphylococcus aureus ATCC 25923". Trop Biomed. 24 (1): 105–9. PMID 17568383.

- ↑ Friedrich CL, Moyles D, Beveridge TJ, Hancock RE (2000). "Antibacterial action of structurally diverse cationic peptides on gram-positive bacteria". Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 44 (8): 2086–92. doi:10.1128/AAC.44.8.2086-2092.2000. PMC 90018

. PMID 10898680.

. PMID 10898680. - ↑ Balkwill DL, Stevens SE (1980). "Effects of penicillin G on mesosome-like structures in Agmenellum quadruplicatum". Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 17 (3): 506–9. doi:10.1128/aac.17.3.506. PMC 283817

. PMID 6775592.

. PMID 6775592. - ↑ Culp, S. (1994). "Defending Robustness: The Bacterial Mesosome as a Test Case". PSA: Proceedings of the Biennial Meeting of the Philosophy of Science Association. 1994: 46–57. JSTOR 193010.

- ↑ Rasmussen, N. (2001). "Evolving Scientific Epistemologies and the Artifacts of Empirical Philosophy of Science: A Reply Concerning Mesosomes" (PDF). Biology and Philosophy. 16 (5): 627–652. doi:10.1023/A:1012038815107. Retrieved 2008-03-07.

- ↑ Allchin, D. (2000). "The Epistemology of Error" (PDF). Philosophy of Science Association Meetings, Vancouver, November. Retrieved 2008-03-08.

Further reading

- Fritz H. Kayser, M.D. (2005). "Color Atlas of Medical Microbiology.Kayser, Medical Microbiology © 2005 Thieme".