Mie scattering

The Mie solution to Maxwell's equations (also known as the Lorenz–Mie solution, the Lorenz–Mie–Debye solution or Mie scattering) describes the scattering of an electromagnetic plane wave by a homogeneous sphere. The solution takes the form of an infinite series of spherical multipole partial waves. It is named after Gustav Mie.

The term "Mie solution" is also used for solutions of Maxwell's equations for scattering by stratified spheres or by infinite cylinders, or other geometries where one can write separate equations for the radial and angular dependence of solutions. The term Mie theory is sometimes used for this collection of solutions and methods; it does not refer to an independent physical theory or law. More broadly, "Mie scattering" suggests situations where the size of the scattering particles is comparable to the wavelength of the light, rather than much smaller or much larger.

Introduction

A modern formulation of the Mie solution to the scattering problem on a sphere can be found in many books, e.g., J. A. Stratton's Electromagnetic Theory.[1] In this formulation, the incident plane wave as well as the scattering field is expanded into radiating spherical vector wave functions. The internal field is expanded into regular spherical vector wave functions. By enforcing the boundary condition on the spherical surface, the expansion coefficients of the scattered field can be computed.

For particles much larger or much smaller than the wavelength of the scattered light there are simple and excellent approximations that suffice to describe the behaviour of the system. But for objects whose size is similar to the wavelength, e.g., water droplets in the atmosphere, latex particles in paint, droplets in emulsions including milk, and biological cells and cellular components, a more exact approach is necessary.[2]

The Mie solution[3] is named after its developer, German physicist Gustav Mie. Danish physicist Ludvig Lorenz and others independently developed the theory of electromagnetic plane wave scattering by a dielectric sphere.

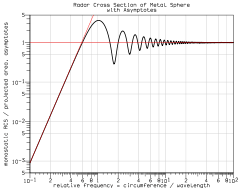

The formalism allows the calculation of the electric and magnetic fields inside and outside a spherical object and is generally used to calculate either how much light is scattered, the total optical cross section, or where it goes, the form factor. The notable features of these results are the Mie resonances, sizes that scatter particularly strongly or weakly.[4] This is in contrast to Rayleigh scattering for small particles and Rayleigh–Gans–Debye scattering (after Lord Rayleigh, Richard Gans and Peter Debye) for large particles. The existence of resonances and other features of Mie scattering, make it a particularly useful formalism when using scattered light to measure particle size.

Mie scattering code

Mie solutions are implemented in a number of programs written in different computer languages such as Fortran, MATLAB, Mathematica. These solutions are in terms of infinite series and include calculation of scattering phase function, extinction, scattering, and absorption efficiencies, and other parameters such as asymmetry parameter or radiation torque. Current usage of a "Mie solution" indicates a series approximation to a solution of Maxwell's equations. There are several known objects which allow such a solution: spheres, concentric spheres, infinite cylinders, cluster of spheres and cluster of cylinders. There are also known series solutions for scattering on ellipsoidal particles. For a list of these specialized codes, examine these articles:

- Codes for electromagnetic scattering by spheres — solutions for single sphere, coated spheres, multilayer sphere, cluster of spheres

- Codes for electromagnetic scattering by cylinders — solutions for single cylinder, multilayer cylinders, cluster of cylinders.

A generalization that allows for a treatment of more general shaped particles is the T-matrix method, which also relies on the series approximation to solutions of Maxwell's equations.

Approximations

Rayleigh approximation (scattering)

Rayleigh scattering describes the elastic scattering of light by spheres which are much smaller than the wavelength of light. The intensity, I, of the scattered radiation is given by

where I0 is the light intensity before the interaction with the particle, R is the distance between the particle and the observer, θ is the scattering angle, n is the refractive index of the particle, and d is the diameter of the particle.

It can be seen from the above equation that Rayleigh scattering is strongly dependent upon the size of the particle and the wavelengths. The intensity of the Rayleigh scattered radiation increases rapidly as the ratio of particle size to wavelength increases. Furthermore, the intensity of Rayleigh scattered radiation is identical in the forward and reverse directions.

The Rayleigh scattering model breaks down when the particle size becomes larger than around 10% of the wavelength of the incident radiation. In the case of particles with dimensions greater than this, Mie's scattering model can be used to find the intensity of the scattered radiation. The intensity of Mie scattered radiation is given by the summation of an infinite series of terms rather than by a simple mathematical expression. It can be shown, however, that Mie scattering differs from Rayleigh scattering in several respects; it is roughly independent of wavelength and it is larger in the forward direction than in the reverse direction. The greater the particle size, the more of the light is scattered in the forward direction.

The blue colour of the sky results from Rayleigh scattering, as the size of the gas particles in the atmosphere is much smaller than the wavelength of visible light. Rayleigh scattering is much greater for blue light than for other colours due to its shorter wavelength. As sunlight passes through the atmosphere, its blue component is Rayleigh scattered strongly by atmospheric gases but the longer wavelength (e.g. red/yellow) components are not. The sunlight arriving directly from the sun therefore appears to be slightly yellow while the light scattered through rest of the sky appears blue. During sunrises and sunsets, the effect of Rayleigh scattering on the spectrum of the transmitted light is much greater due to the greater distance the light rays have to travel through the high density air near the earth's surface.

In contrast, the water droplets which make up clouds are of a comparable size to the wavelengths in visible light, and the scattering is described by Mie's model rather than that of Rayleigh. Here, all wavelengths of visible light are scattered approximately identically and the clouds therefore appear to be white or grey.

Rayleigh Gans Approximation

The Rayleigh Gans Approximation is an approximate solution to light scattering when the relative refractive index of the particle is close to unity, and its size is much smaller in comparison to the wavelength of light divided by |n−1|, where n is the refractive index.

Anomalous diffraction approximation of van de Hulst

The Anomalous diffraction approximation is valid for large and optically soft spheres. The extinction efficiency in this approximation is given by

where Q is the efficiency factor of scattering, which is defined as the ratio of the scattering cross section and geometrical cross section πa2;

p = 4πa(n– 1)/λ has as its physical meaning, the phase delay of the wave passing through the centre of the sphere;

where a is the sphere radius, n is the ratio of refractive indices inside and outside of the sphere, and λ the wavelength of the light.

This set of equations was first described by van de Hulst in (1957).[4]

Applications

Mie theory is very important in meteorological optics, where diameter-to-wavelength ratios of the order of unity and larger are characteristic of many problems regarding haze and cloud scattering. A further application is in the characterization of particles via optical scattering measurements. The Mie solution is also important for understanding the appearance of common materials like milk, biological tissue and latex paint.

Atmospheric science

Mie scattering occurs when the diameters of atmospheric particles are similar to the wavelengths of the scattered light. Dust, pollen, smoke and microscopic water droplets are common causes of Mie scattering. Mie scattering occurs mostly in the lower portions of the atmosphere where larger particles are more abundant, and dominates in cloudy conditions.

Cancer detection and screening

Mie theory has been used to determine if scattered light from tissue corresponds to healthy or cancerous cell nuclei using angle-resolved low-coherence interferometry.

Magnetic particles

A number of unusual electromagnetic scattering effects occur for magnetic spheres. When the relative permittivity equals the permeability, the back-scatter gain is zero. Also, the scattered radiation is polarized in the same sense as the incident radiation. In the small-particle (or long-wavelength) limit, conditions can occur for zero forward scatter, for complete polarization ofscattered radiation in other directions, and for asymmetry of forward scatter to backscatter. The special case in the small-particle limit provides interesting special instances of complete polarization and forward-scatter-to-backscatter asymmetry.[5]

Metamaterial

Mie theory has been used to design metamaterials. This type of metamaterial is usually consisted of three-dimensional composites of metal or non-metallic inclusions periodically or randomly embedded in a low permittivity matrix. In such a scheme, the negative constitutive parameters are designed to appear around the Mie resonances of the inclusions: the negative effective permittivity is designed around the resonance of the Mie electric dipole scattering coefficient whereas negative effective permeability is designed around the resonance of the Mie magnetic dipole scattering coefficient, and double negative (DNG) is designed around the overlap of resonances of Mie electric and magnetic dipole scattering coefficients. The particle usually have the following combinations:

1) one set of magnetodielectric particles with values of relative permittivity and permeability much greater than one and close to each other;

2) two different dielectric particles with equal permittivity but different size;

3) two different dieletric particles with equal size but different permittivity.

In theory, the particles analyzed by Mie theory are commonly spherical but, in practice, particles are usually fabricated as cubes or cylinders for ease of fabrication. To meet the criteria of homogenization, which may be stated in the form that the lattice constant is much smaller than the operating wavelength, the relative permittivity of the dielectric particles should be much greater than 1, e.g. to achieve negative effective permittivity (permeability).[6] [7] [8]

Particle sizing

Mie theory is commercially applied in laser diffraction analysis. While early computers in the 1970s were only able to compute diffraction data with the more simple Fraunhofer approximation, Mie is widely used since the 1990s and officially recommended for particles below 50 micrometers in guideline ISO 13321:2009.[9]

Mie theory has been used in the detection of oil concentration in polluted water.[10][11]

Mie scattering is the primary method of sizing single sonoluminescing bubbles of air in water,[12][13][14] and is valid for cavities in materials as well as particles in materials as long as the surrounding material is essentially non-absorbing.

Parasitology

It has also been used to study the structure of Plasmodium falciparum, a particularly pathogenic form of malaria.[15]

See also

- Computational electromagnetics

- Light scattering by particles

- List of atmospheric radiative transfer codes

- Optical properties of water and ice

References

- ↑ Stratton, J. A. (1941). Electromagnetic Theory. New York: McGraw-Hill.

- ↑ Bohren, C. F.; Huffmann, D. R. (2010). Absorption and scattering of light by small particles. New York: Wiley-Interscience. ISBN 3-527-40664-6.

- ↑ Mie, Gustav (1908). "Beiträge zur Optik trüber Medien, speziell kolloidaler Metallösungen". Annalen der Physik. 330 (3): 377–445. Bibcode:1908AnP...330..377M. doi:10.1002/andp.19083300302. English translation, American translation

- 1 2 van de Hulst, H. C. (1957). Light scattering by small particles. New York: John Wiley and Sons. ISBN 9780486139753.

- ↑ Kerker, M.; Wang, D.-S.; Giles, C. L. (1983). "Electromagnetic scattering by magnetic spheres" (PDF). Journal of the Optical Society of America. 73 (6): 765. doi:10.1364/JOSA.73.000765. ISSN 0030-3941.

- ↑ Holloway, C. L.; Kuester, E. F.; Baker-Jarvis, J.; Kabos, P. (2003). "A double negative (DNG) composite medium composed of magnetodielectric spherical particles embedded in a matrix". IEEE Transactions on Antennas and Propagations. 51 (10): 2596–2603. Bibcode:2003ITAP...51.2596H. doi:10.1109/TAP.2003.817563.

- ↑ Zhao, Q.; Zhou, J.; Zhang, F. L.; Lippens, D. (2009). "Mie resonance-based dielectric metamaterials". Materials Today. 12 (12): 60–69. doi:10.1016/S1369-7021(09)70318-9.

- ↑ Li, Y.; Bowler, N. (2012). "Traveling waves on three-dimensional periodic arrays of two different magnetodielectric spheres arbitrarily arranged on a simple tetragonal lattice". IEEE Transactions on Antennas and Propagations. 60 (6): 2727–2739. Bibcode:2012ITAP...60.2727L. doi:10.1109/tap.2012.2194637.

- ↑ "ISO 13320:2009 - Particle size analysis -- Laser diffraction methods". www.iso.org. Retrieved 2015-11-02.

- ↑ He, L; Kear-Padilla, L.L; Lieberman, S.H; Andrews, J.M (2003). "Rapid in situ determination of total oil concentration in water using ultraviolet fluorescence and light scattering coupled with artificial neural networks". Analytica Chimica Acta. 478 (2): 245. doi:10.1016/S0003-2670(02)01471-X.

- ↑ Lindner, H; Fritz, Gerhard; Glatter, Otto (2001). "Measurements on Concentrated Oil in Water Emulsions Using Static Light Scattering". Journal of Colloid and Interface Science. 242: 239. doi:10.1006/jcis.2001.7754.

- ↑ Gaitan, D. Felipe; Lawrence A. Crum; Charles C. Church; Ronald A. Roy (1992). "Sonoluminescence and bubble dynamics for a single, stable, cavitation bubble". The Journal of the Acoustical Society of America. 91 (6): 3166. Bibcode:1992ASAJ...91.3166G. doi:10.1121/1.402855. Retrieved 17 November 2013.

- ↑ Lentz, W. J.; Atchley, Anthony A.; Gaitan, D. Felipe (May 1995). "Mie scattering from a sonoluminescing air bubble in water". Applied Optics. 34 (15): 2648. Bibcode:1995ApOpt..34.2648L. doi:10.1364/AO.34.002648.

- ↑ Gompf, B.; Pecha, R. (May 2000). "Mie scattering from a sonoluminescing bubble with high spatial and temporal resolution". Physical Review E. 61 (5): 5253–5256. Bibcode:2000PhRvE..61.5253G. doi:10.1103/PhysRevE.61.5253.

- ↑ Serebrennikova, Yulia M.; Patel, Janus; Garcia-Rubio, Luis H. (2010). "Interpretation of the ultraviolet-visible spectra of malaria parasite Plasmodium falciparum". Applied Optics. 49 (2): 180–8. Bibcode:2010ApOpt..49..180S. doi:10.1364/AO.49.000180. PMID 20062504.

Further reading

- Kerker, M. (1969). The scattering of light and other electromagnetic radiation. New York: Academic.

- Barber, P. W.; Hill, S. S. (1990). Light scattering by particles: Computational methods. Singapore: World Scientific. ISBN 9971-5-0813-3.

- Mishchenko, M.; Travis, L.; Lacis, A. (2002). Scattering, Absorption, and Emission of Light by Small Particles. New York: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-78252-X.

- Frisvad, J.; Christensen, N.; Jensen, H. (2007). "Computing the Scattering Properties of Participating Media using Lorenz-Mie Theory". ACM Transactions on Graphics. 26 (3): 60. doi:10.1145/1276377.1276452.

- Wriedt, Thomas (2008). "Mie theory 1908, on the mobile phone 2008". Journal of Quantitative Spectroscopy & Radiative Transfer. 109 (8): 1543–1548. Bibcode:2008JQSRT.109.1543W. doi:10.1016/j.jqsrt.2008.01.009.

- Lorenz, Ludvig (1890). "Lysbevaegelsen i og uden for en af plane Lysbolger belyst Kugle". Det Kongelige Danske Videnskabernes Selskabs Skrifter. 6. Raekke, 6. Bind (1): 1–62.

External links

- JMIE (2D C++ code to calculate the analytical fields around an infinite cylinder, developed by Jeffrey M. McMahon)

- Collection of light scattering codes

- www.T-Matrix.de. Implementations of Mie solutions in FORTRAN, C++, IDL, Pascal, Mathematica and Mathcad

- ScatLab. Mie scattering software for Windows.

- Online Mie solution calculator is available, with documentation in German and English.

- Online Mie scattering calculator produces beautiful graphs over a range of parameters.

- phpMie Online Mie scattering calculator written on PHP.

- Mie resonance mediated light diffusion and random lasing.

- Mie solution for spherical particles.