Monsieur D'Olive

Monsier D'Olive is an early Jacobean era stage play, a comedy written by George Chapman.

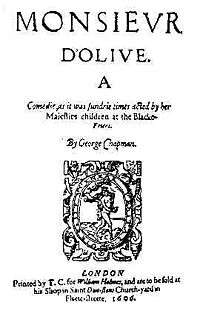

The play was first published in 1606, in a quarto printed by Thomas Creede for the bookseller William Holmes. This was the drama's sole edition before the 19th century. The title page identifies Chapman as the author, and states that the play was performed by the Queen's Revels Children at the Blackfriars Theatre.[1] The play was almost certainly written and debuted onstage in 1605.[2]

Chapman structured his main plot to express his interest in the Neoplatonist philosophy of Marsilio Ficino.[3] Critics have been divided as to the success of Chapman's effort and the value of the resulting play. 19th-century critics often praised Monsieur D'Olive as one of Chapman's best comedies. 20th-century scholars, beginning with T. M. Parrott, have tended to judge the play more harshly. In some modern judgments, "the play is sterile;" its romance collapses "into mechanical intrigue."[4]

Synopsis

The drama's main plot centers on Vandome, a French gentleman and nephew to the King of France. He returns from a three-years' journey abroad as a merchant, to find that the personal lives of his friends and family are strangely disordered. He had previously kept up a chivalrous, courtly, and platonic affection with Marcellina, the wife of his friend the Count Vaumont. She missed Vandome so intensely, once he'd left on his travels, that her husband was provoked to a jealous outburst; and as a result, the offended countess has retreated into a life of seclusion, sleeping by day and waking by night. Vandome also discovers that his sister has died in his absence — and that her husband, the Earl of St. Anne, has been so overcome with grief that he has had his late wife's body embalmed, to keep at home and mourn over. Vandome is left to sort out the emotional problems of his friends and restore a semblance of balance and sanity to their little society.

Marcellina's sister Eurione has joined her sister in her nocturnal lifestyle; she perversely idealizes both the Countess and the Earl. Vandome realizes that this idealization masks Eurione's romantic attraction to St. Anne — which gives him a potential solution to the Earl's predicament. He tells St. Anne that he, Vandome, is in love with Eurione, and solicits the Earl to act as his go-between. Their old friendship leads the Earl to acquiesce to Vandome's request; and once Vandome had gotten the Earl and Eurione together, he bows out of his fictitious attraction and lets nature take its course. The Earl of St. Anne and Eurione are betrothed at the play's end.

Vandome takes a different approach to the Countess Marcellina's problem. Early one morning, as Marcellina and Eurione are about to retire for their day's night, Vandome interrupts them with a false report of the Count Vaumont's infidelity. Vandome works on their emotions so persuasively that the two women go to find Vaumont and confront him about his alleged unfaithfulness. When they reach the local Duke's court, only to realize that the story is false, the Duke thanks them for their attendance on his Duchess. Marcellina's spell of self-imposed nocturnal isolation has been broken.

The play, however, draws its title from the central character of its comic subplot. Monsieur D'Olive is a satirical portrait of a Jacobean gallant, foppish, vain, pompous, verbose and fantastical, and liable to be duped through his own excesses of character and ego. He conceives himself a wit, though he is rendered wit's victim by the tricks of two joking courtiers. Mugeron and Rodrigue trick D'Olive into thinking that he has been appointed to an important foreign embassy...and that he must act the part. In attempting to do so, D'Olive embarrasses himself at the Duke's court, giving long-winded speeches about tobacco and kissing the Duchess. The two courtiers further play upon D'Olive by sending him a forged love letter from a prominent lady of the Duke's court; when he comes in disguise to meet his inamorata, he is exposed again.

External links

References

- ↑ E. K. Chambers, The Elizabethan Stage. 4 Volumes, Oxford, Clarendon Press, 1923; Vol. 3, p. 252.

- ↑ Albert H. Tricomi, "The Focus of Satire and the Date of Monsieur D'Olive," Studies in English Literature, 1500–1900, Vol. 17 No. 2 (Spring 1977), pp. 281–94.

- ↑ A. P. Hogan, "Thematic Unity in Chapman's Monsieur D'Olive." Studies in English Literature, 1500–1900, Vol. 11 No. 2 (Spring 1971), pp. 295–306.

- ↑ A. P. Hogan and Thomas Mark Grant, quoted in: Terence P. Logan and Denzell S. Smith, eds., The New Intellectuals: A Survey and Bibliography of Recent Studies in English Renaissance Drama. Lincoln, NE, University of Nebraska Press, 1977; p. 146.