Mucuna pruriens

| Mucuna pruriens | |

|---|---|

| |

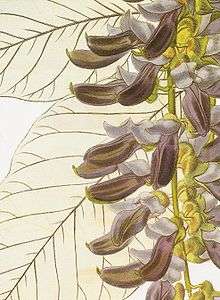

| Mucuna pruriens inflorescence | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| (unranked): | Angiosperms |

| (unranked): | Eudicots |

| (unranked): | Rosids |

| Order: | Fabales |

| Family: | Fabaceae |

| Subfamily: | Faboideae |

| Tribe: | Phaseoleae |

| Genus: | Mucuna |

| Species: | M. pruriens |

| Binomial name | |

| Mucuna pruriens (L.) DC. | |

| Synonyms[1] | |

| |

Mucuna pruriens is a tropical legume native to Africa and tropical Asia and widely naturalized and cultivated.[2] Its English common names include velvet bean, Bengal velvet bean, Florida velvet bean, Mauritius velvet bean, Yokohama velvet bean, cowage, cowitch, lacuna bean, and Lyon bean.[2] The plant is notorious for the extreme itchiness it produces on contact,[3] particularly with the young foliage and the seed pods. It has value in agricultural and horticultural use and has a range of medicinal properties.

Description

_in_Kawal%2C_AP_W2_IMG_1506.jpg)

The plant is an annual climbing shrub with long vines that can reach over 15 metres (50 ft) in length. When the plant is young, it is almost completely covered with fuzzy hairs, but when older, it is almost completely free of hairs. The leaves are tripinnate, ovate, reverse ovate, rhombus-shaped or widely ovate. The sides of the leaves are often heavily grooved and the tips are pointy. In young M. pruriens plants, both sides of the leaves have hairs. The stems of the leaflets are two to three millimeters long (approximately one tenth of an inch). Additional adjacent leaves are present and are about 5 millimetres (0.2 in) long.

The flower heads take the form of axially arrayed panicles. They are 15–32 centimetres (6–13 in) long and have two or three, or many flowers. The accompanying leaves are about 12.5 millimetres (0.5 in) long, the flower stand axes are from 2.5–5 millimetres (0.1–0.2 in). The bell is 7.5–9 millimetres (0.3–0.4 in) long and silky. The sepals are longer or of the same length as the shuttles. The crown is purplish or white. The flag is 1.5 millimetres (0.06 in) long. The wings are 2.5–3.8 centimetres (1.0–1.5 in) long.

In the fruit-ripening stage, a 4–13 centimetres (2–5 in) long, 1–2 centimetres (0.4–0.8 in) wide, unwinged, leguminous fruit develops. There is a ridge along the length of the fruit. The husk is very hairy and carries up to seven seeds. The seeds are flattened uniform ellipsoids, 1–1.9 centimetres (0.4–0.7 in) long, .8–1.3 centimetres (0.3–0.5 in) wide and 4–6.5 centimetres (2–3 in) thick. The hilum, the base of the funiculus (connection between placenta and plant seeds) is a surrounded by a significant arillus (fleshy seed shell).

M.pruriens bears white, lavender, or purple flowers. Its seed pods are about 10 cm (4 inches) long[4] and are covered in loose, orange hairs that cause a severe itch if they come in contact with skin. The itch is caused by a protein known as mucunain.[5] The seeds are shiny black or brown drift seeds.

The dry weight of the seeds is 55–85 grams (2–3 oz)/100 seeds.[6]

Uses

In many parts of the world Mucuna pruriens is used as an important forage, fallow and green manure crop.[7] Since the plant is a legume, it fixes nitrogen and fertilizes soil. In Indonesia, particularly Java the beans are eaten and widely known as 'Benguk'. The beans can also be fermented to form a food similar to tempe and known as Benguk tempe or 'tempe Benguk'.

M. pruriens is a widespread fodder plant in the tropics. To that end, the whole plant is fed to animals as silage, dried hay or dried seeds. M. pruriens silage contains 11-23% crude protein, 35-40% crude fiber, and the dried beans 20-35% crude protein. It also has use in the countries of Benin and Vietnam as a biological control for problematic Imperata cylindrica grass.[7] M. pruriens is said to not be invasive outside its cultivated area.[7] However, the plant is known to be invasive within conservation areas of South Florida, where it frequently invades disturbed land and rockland hammock edge habitats.

M. pruriens is sometimes used as a coffee substitute.

Cooked fresh shoots or beans can also be eaten. M. pruriens contains relatively high (3–7% dry weight) levels of L-DOPA, an essential compound in human metabolism. Some people are sensitive to ingestion of high levels of L-DOPA and may experience symptoms such as nausea, vomiting, cramping, arrhythmias, and hypotension. Up to 99% of the L-DOPA can be leached out of M. pruriens by soaking in boiling water for 40 minutes, changing the water, and then soaking in cold water. Acidic water significantly increases the rate at which L-DOPA is leached out. The beans may then be cooked by any method desired. Pre-boiling also contributes to better decomposition of anti-nutrients found in M. pruriens through cooking.[8]

Traditional medicine

The seeds of Mucuna pruriens have been used for treating many dysfunctions in Tibb-e-Unani (Unani Medicine).[9] It is also used in Ayurvedic medicine.

The plant and its extracts have been long used in tribal communities as a toxin antagonist for various snakebites. It has been studied for its effects against bites by Naja spp. (cobra),[10] Echis (Saw scaled viper),[11] Calloselasma (Malayan Pit viper) and Bangarus (Krait).[12]

It has long been used in traditional Ayurvedic Indian medicine in an attempt to treat diseases including Parkinson's disease.[13]

It is also used in Siddha system of medicine for various purposes.

Dried leaves of M. pruriens are sometimes smoked.[4]

Itch-inducing properties

The hairs lining the seed pods contain serotonin and the protein mucunain which cause severe itching when the pods are touched.[3][14][15] The calyx below the flowers is also a source of itchy spicules and the stinging hairs on the outside of the seed pods are used in itching powder.[3][16] Scratching the exposed area can spread the itching to other areas touched. Once this happens, the subject tends to scratch vigorously and uncontrollably and for this reason the local populace in northern Mozambique refer to the beans as "mad beans" (feijões malucos). The seed pods are known as "Devil Beans" in Nigeria.

Pharmacology

The seeds of the plant contain about 3.1–6.1% L-DOPA,[14] with trace amounts of serotonin, nicotine, and bufotenine.[17] One study using 36 samples of seeds found no tryptamines present.[18]

Nomenclature and taxonomy

Common names

- Frijol de Abono in the Guatemala language

- "Nkasi" in Nyanja of Zambia and "Sepe" in Bemba of Zambia

- Bieh in the Madurese language

- Ci mao li dou 刺毛黧豆 in Chinese

- Nasagunnikaayi ([ನಸಗೂನ್ಣೆಕಾಯಿ]) in Kannada

- Kara benguk in the Javanese language

- Atmagupta (आत्मगुप्ता) or Kapikacchu (कपिकच्छु) in Sanskrit

- Kiwanch (किवांच) or Kooch (कोंच) in Hindi

- Khaajkuiri in Marathi

- Alkushi/আলকুশি (Bengali)

- Poonaikkaali (பூனைக்காலி) in Tamil

- Juckbohne (German: "itch bean")[4]

- Fogareté (Dominican Republic); Picapica (everywhere), in Spanish

- Kapikachu

- Werepe or YerepeYoruba

- "Devil Beans" (Nigeria) in English

- Duradagondi(దురదగొండి) or 'Dulagondi' in Telugu

- Feijão maluco, "mad bean" (Angola and Mozambique); pó-de-mico, "itching powder", feijão-da-flórida, "Florida's bean", feijão-cabeludo-da-índia, "hairy/pilous Indian bean", feijão-de-gado, "cattle's bean", feijão-mucuna, "mucuna bean", feijão-veludo, "velvet bean", and mucuna-vilosa, "fleecy mucuna" (Brazil and Portugal), in Portuguese

- Chitedze (Malawi)

- Naykuruna (ML:നായ്ക്കുരണ) (Malayalam)

- Mah mui (TH: หมามุ่ย) in Thai

- Đậu mèo rừng, đậu ngứa, móc mèo in Vietnamese

- Kavach beej

- Yèrènkpè Nupe

- Inyelekpe (Nigeria) in Igala

- Upupu in Kiswahili

- Baidanka ବାଇଡଙ୍କin Oriya

- Pois mascate (Reunion Island) in French

- Wandhuru Mæ in Sinhala

- Kway lee yerr thee in Myanmar

- Agbala (Nigeria) in Ibo

- "Bandar Kekowa" (বান্দৰ কেকোঁৱা) in Assamese

- "picapica (puerto rico).

- Akpakru (Nigeria)Bekwarra

- "Kauchho" or "Kauso" (काउछो / काउसो ) in Nepali

- Mamui (หมามุ่ย) in Thai

- "Huriri" (Zimbabwe)in Shona

- "Gajelbeliyan in Kangari language of Himachal Pradesh, India

Subspecies

- Mucuna pruriens ssp. deeringiana (Bort) Hanelt

- Mucuna pruriens ssp. pruriens[4]

Varieties

- Mucuna pruriens var. hirsuta (Wight & Arn.) Wilmot-Dear[19]

- Mucuna pruriens var. pruriens (L.) DC. [20]

- Mucuna pruriens var. sericophylla[19]

- Mucuna pruriens var. utilis (Wall. ex Wight) L.H.Bailey is the non-stinging variety grown in Honduras.[21]

See also

References

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Mucuna pruriens. |

| Wikibooks Cookbook has a recipe/module on |

- ↑ "The Plant List: A Working List of All Plant Species". Retrieved 8 March 2015.

- 1 2 "USDA GRIN Taxonomy". Retrieved 8 March 2015.

- 1 2 3 Andersen, Hjalte Holm; Elberling, Jesper P.; Arendt-Nielsen, Lars (2015). "Human Surrogate Models of Histaminergic and Non-histaminergic Itch". Acta Dermato-Venereologica. Epub ahead of print: 771–7. doi:10.2340/00015555-2146. PMID 26015312.

- 1 2 3 4 Rätsch, Christian. Enzyklopädie der psychoaktiven Pflanzen. Botanik, Ethnopharmakologie und Anwendungen. Aarau: AT-Verl. p. 15. ISBN 978-3-85502-570-1.

- ↑ Reddy, V.B.; et al. (2008). "Cowhage-evoked itch is mediated by a novel cysteine protease: a ligand of protease-activated receptors". J. Neurosci. 28 (17): 4331–4335. doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0716-08.2008. PMC 2659338

. PMID 18434511.

. PMID 18434511. - ↑ "Factsheet - Mucuna pruriens". www.tropicalforages.info. Retrieved 2008-02-23.

- 1 2 3 "Factsheet - Mucuna pruriens". www.tropicalforages.info. Retrieved 2008-05-21.

- ↑ Nyirenda, D. "The effects of different processing methods of velvet beans (Mucuna pruriens) on L-dopa content, proximate composition and broiler chicken performance" (PDF). Scientific Information System Redalyc. Retrieved 14 May 2016.

- ↑ Amin KMY, Khan MN, Hakim Syed Zillur Rahman, et al. (1996). "Sexual function improving effect of Mucuna pruriens in sexually normal male rats". Fitoterapia. 67 (1): 53–58.

The seeds of M. pruriens are used for treating sexual dysfunction in Tibb-e-Unani (Unani Medicine), the traditional system of medicine of Indian subcontinent

- ↑ Tan, NH; Fung, SY; Sim, SM; Marinello, E; Guerranti, R; Aguiyi, JC (2009). "The protective effect of Mucuna pruriens seeds against snake venom poisoning". Journal of Ethnopharmacology. 123 (2): 356–8. doi:10.1016/j.jep.2009.03.025. PMID 19429384.

- ↑ "Characterization of the factor responsible for the antisnake activity of Mucuna Pruriens' seeds" (PDF). Journal of Preventive Medicine and Hygiene. 40: 25–28. 1999.

- ↑ http://sphinxsai.com/sphinxsaiVol_2No.1/PharmTech_Vol_2No.1/PharmTech_Vol_2No.1PDF/PT=132%20(870-874).pdf

- ↑ Katzenschlager, R; Evans, A; Manson, A; Patsalos, PN; Ratnaraj, N; Watt, H; Timmermann, L; Van Der Giessen, R; Lees, AJ (2004). "Mucuna pruriens in Parkinson's disease: a double blind clinical and pharmacological study". Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery & Psychiatry. 75 (12): 1672–7. doi:10.1136/jnnp.2003.028761. PMC 1738871

. PMID 15548480.

. PMID 15548480. - 1 2 Medical Toxicology - Google Book Search. books.google.com. 2004. ISBN 978-0-7817-2845-4. Retrieved 2008-03-15.

- ↑ YERRA RAJESHWAR, MALAYA GUPTA and UPAL KANTI MAZUMDER (2005). "In Vitro Lipid Peroxidation and Antimicrobial Activity of Mucuna pruriens Seeds". IJPT. 4: 32–35.

- ↑ G. V. Joglekar, M. B. Bhide J. H. Balwani. An experimental method for screening antipruritic agents. British Journal of Dermatology. Volume 75 Issue 3 Page 117 - March 1963

- ↑ "Species Information". sun.ars-grin.gov. Retrieved 2008-03-02.

- ↑ "The phytochemistry, toxicology, and food potential of velvetbean". www.idrc.ca. Archived from the original on May 31, 2008. Retrieved 2008-03-02.

- 1 2 "Mucuna pruriens information from NPGS/GRIN". www.ars-grin.gov. Retrieved 2008-02-23.

- ↑ Picapica

- ↑ http://drugpolicycentral.com/bot/index.cgi?xfml=1&max=100

External links

- www.fao.org

- Mucuna pruriens (U.S. Forest Service)

- www.hort.purdue.edu Crop Fact Sheets

- Mucuna pruriens (Tropical Forages)

- Mucuna pruriens protects against snakebite venom

- Mucuna pruriens var. utilis (Photos)

- Chemicals in: Mucuna pruriens (L.) DC. (Dr. Duke's Phytochemical and Ethnobotanical Databases)

- Lycaeum

- Mucuna pruriens a Comprehensive Review

- Mucuna pruriens Seed L-DOPA Content on the Basis of Seed Color

- Research Paper Showing Quantitative Phytochemical Analysis

- Caldecott, Todd (2006). Ayurveda: The Divine Science of Life. Elsevier/Mosby. ISBN 0-7234-3410-7. Contains a detailed monograph on Mucuna pruriens (Kapikacchu, Atmagupta) as well as a discussion of health benefits and usage in clinical practice. Available online at http://www.toddcaldecott.com/index.php/herbs/learning-herbs/349-kapikachu