Mycovirus

Mycoviruses (ancient Greek μύκης mykes: fungus and Latin virus) are viruses that infect fungi. The majority of mycoviruses have double-stranded RNA (dsRNA) genomes and isometric particles, but approximately 30% have positive sense, single-stranded RNA (+ssRNA) genomes.[1][2] To be a true mycovirus, they must demonstrate an ability to be transmitted - in other words be able to infect other healthy fungi. Many double stranded RNA elements that have been described in fungi do not fit this description, and in these cases they are referred to as virus like particles or VLPs. Preliminary results indicate that most mycoviruses codiverge with their hosts, i.e. their phylogeny is largely congruent with the one of their hosts.[3] However, many virus families containing mycoviruses have only sparsely been sampled.

Mycovirology

Mycovirology[4] is the study of viruses infecting fungi, also called mycoviruses. It is a special subdivision of the general field of virology and describes taxonomy, host range, origin and evolution, transmission and movement of mycoviruses and their impact on host phenotype.

History

The first record of an economic impact of mycoviruses on fungi was recorded in cultivated mushrooms (Agaricus bisporus) in the late 1940s and was called the La France disease.[5] Hollings found more than three different types of viruses in the abnormal sporophores. This report marks the beginning of mycovirology.[4]

The La France Disease is also known as X disease, watery stripe, dieback and brown disease. Symptoms include:

- Reduced yield

- Slow and aberrant mycelial growth

- Waterlogging of tissue

- malformation

- Premature maturation

- Increased post-harvest deterioration (reduced shelf life)[6]

Mushrooms have shown no resistance to the virus, and so control has had to be via hygienic practises to stop the spread of the virus.

However, the best known mycovirus is Cryphonectria parasitica hypovirus 1 (CHV1). CHV1 is exceptional amongst mycoviral research due its success as biocontrol agent against chestnut blight in Europe, but also because it is a model organism for studying hypovirulence in fungi. However, this system is only being used in Europe routinely, because of the relative small number of vegetative compatibility groups (VCGs) on this continent. In contrast, in North America the distribution of the hypovirulent phenotype is often prevented because fungal hyphae cannot fuse and exchange their cytoplasmic content due to an incompatibility reaction. In the United States of America at least 35 VCGs were found.[7] A similar situation seems to be present in China and Japan where 71 VCGs were identified so far.[8]

Taxonomy

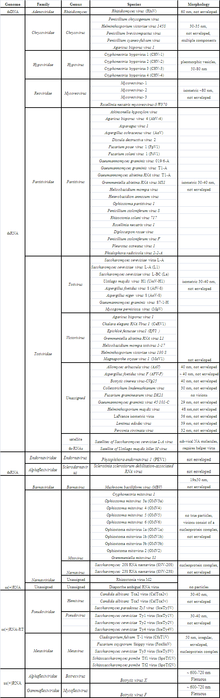

The majority of mycoviruses have double-stranded RNA (dsRNA) genomes and isometric particles, but approximately 30% have positive sense, single-stranded RNA (+ssRNA) genomes.[1][2] So far there is only one true example of a single-stranded DNA (ssDNA) mycovirus. A geminivirus-related virus was found in Sclerotinia sclerotiorum conferring hypovirulence to its host.[9] The updated 9th ICTV report on virus taxonomy[10] lists over 90 mycovirus species covering 10 viral families, of which 20% were unassigned to a genus or sometimes not even to a family. Isometric forms predominate mycoviral morphologies in comparison to rigid rods, flexuous rods, clubshaped particles, enveloped bacilliform particles, and Herpesvirus-like viruses.[11] The lack of genomic data often hampers a conclusive assignment to already established groups of viruses or makes it impossible to erect new families and genera. The latter is true for many unencapsidated dsRNA viruses, which are assumed to be viral, but missing sequence data prevented their classification so far.[1] So far, viruses of the families Partitiviridae, Totiviridae, and Narnaviridae are dominating the ‘mycovirus sphere’.

Host range and incidence

Mycoviruses are common in fungi (Herrero et al., 2009) and are found in all four phyla of the true fungi: Chytridiomycota, Zygomycota, Ascomycota and Basidiomycota. Fungi are frequently infected with two or more unrelated viruses and also with defective dsRNA and/or satellite dsRNA.[12][13] There are also viruses that simply use fungi as vectors and are distinct from mycoviruses, because they cannot reproduce in the fungal cytoplasm.[14] It is generally assumed that the natural host range of mycoviruses is confined to closely related vegetability compatibility groups that allow for cytoplasmic fusion,[15] but some mycoviruses can replicate in taxonomically different fungal hosts.[4] Good examples are mitoviruses found in the two fungal species Sclerotinia homoeocarpa and Ophiostoma novo-ulmi.[16] Furthermore, Nuss et al. (2005) described that it is possible to extend the natural host range of Cryphonectria parasitica hypovirus 1 (CHV1) to several fungal species that are closely related to Cryphonectria parasitica using in vitro virus transfection techniques.[17] CHV1 can also propagate in the genera Endothia and Valsa,[12] which belong to the two distinct families Cryphonectriaceae and Diaporthaceae, respectively.

Origin and evolution

DsRNA as well as ssRNA are assumed to be very ancient and presumably originated from the ‘RNA world’ as both types of RNA viruses infect bacteria as well as eukaryotes.[18] Although the origin of viruses is still not well understood,[19] recently presented data which suggest that viruses invaded the emerging ‘supergroups’ of eukaryotes from an ancestral pool in a very early stage of life on earth. According to Koonin,[19] RNA viruses colonized eukaryotes first and subsequently co-evolved with their hosts. This concept fits well with the proposed ‘ancient co-evolution hypothesis’, which also assumes a long co-evolution of viruses and fungi.[1][11] ‘The ancient coevolution hypothesis’ could contribute some explanation why mycoviruses are so diverse.[11][20] It has also been suggested that it is very likely that plant viruses containing a movement protein have evolved from mycoviruses by introducing of an extracellular phase into their life cycle, rather than eliminating it. Furthermore, the recent discovery of an ssDNA mycovirus tempted some researchers[9] to suggest that RNA and DNA viruses might have common evolutionary mechanisms. However, there are many cases where mycoviruses are grouped together with plant viruses. For example, CHV1 showed phylogenetic relatedness to the ssRNA genus Potyvirus[21] and some ssRNA viruses, which were assumed to confer hypovirulence or debilitation, were often found to be more closely related to plant viruses than to other mycoviruses.[1] Therefore, another theory arose that these viruses moved from a plant host to plant pathogenic fungal host or vice versa. This ‘plant virus hypothesis’ may not explain how mycoviruses developed originally, but it could help to understand how they evolved further.

Transmission

A significant difference between the genomes of mycoviruses to other viruses is the absence of genes for ‘cell-to-cell movement’ proteins. It is therefore assumed that mycoviruses only move intercellularly during cell division (e.g. sporogenesis) or via hyphal fusion.[12][22] Mycoviruses might simply not need an external route of infection as they have many means of transmission and spread due to their fungal host’s life style:

- Plasmogamy and cytoplasmic exchange over extended periods of time

- Production of vast amounts of asexual spores

- Overwintering via sclerotia[23]

- More or less effective transmission into sexual spores

However, there are potential barriers to mycovirus spread due to vegetative incompatibility and variable transmission to sexual spores. Transmission to sexually produced spores can range from 0% to 100% depending on the virus-host combination.[12] Transmission between species of the same genus sharing the same habitat has also been reported including Cryphonectria (C. parasitica and C. sp), Sclerotinia (Sclerotinia sclerotiorum and S. minor), and Ophistoma (O. ulmi and O. novo-ulmi).[24][25] Intraspecies transmission has also been reported[26] between Fusarium poae and black Aspergillus isolates. However, it is not known how fungi overcome the genetic barrier; whether there is some form of recognition process during physical contact or some other means of exchange, such as vectors. Research[27] using Aspergillus species indicated that transmission efficiencies might depend on the hosts viral infection status (infected with no, different, or same virus), and that mycoviruses might play a role in the regulation of secondary mycoviral infection. Whether this is also true for other fungi is not yet known. In contrast to acquiring mycoviruses spontaneously, the loss of mycoviruses seems very infrequent[27] and suggests that either viruses actively moved into spores and new hyphal tips, or the fungus might facilitate the mycoviral transport in some other way.

Movement of mycoviruses within fungi

Although it is not known yet whether viral transport is an active or passive process, it is generally assumed that fungal viruses move forward by plasma streaming.[28] Theoretically they could drift with the cytoplasm as it extends into new hyphae, or attach to the web of microtubuli, which would drag them through the internal cytoplasmic space. That might explain how they pass through septa and bypass woronin bodies. However, some researchers have found them located next to septum walls,[2][29] which could imply that they ‘got stuck’ and were not able to move actively forward themselves. Others have suggested that the transmission of viral mitochondrial dsRNA may play an important role in the movement of mitoviruses found in Botrytis cinerea.[30]

Impact on host phenotype

Phenotypic effects of mycoviral infections can vary from advantageous to deleterious, but most of them are asymptomatic or cryptic. The connection between phenotype and mycovirus presence is not always straight forward. Several reasons may account for this. First, the lack of appropriate infectivity assays often hindered the researcher from reaching a coherent conclusion.[31] Secondly, mixed infection or unknown numbers of infecting viruses make it very difficult to associate a particular phenotypic change with the investigated virus.

Although most mycoviruses often do not seem to disturb their host’s fitness, this does not necessarily mean they are living unrecognized by their hosts. A neutral co-existence might just be the result of a long co-evolutionary process.[32][33] Accordingly, symptoms may only appear when certain conditions of the virus-fungus-system change and get out of balance. This could be external (environmental) as well as internal (cytoplasmic). It is not known yet why some mycoviruses-fungus-combinations are typically detrimental while others are asymptomatic or even beneficial. Nevertheless, harmful effects of mycoviruses are economically interesting, especially if the fungal host is a phytopathogen and the mycovirus could be exploited as biocontrol agent. The best example is represented by the case of CHV1 and C. parasitica.[12] Other examples of deleterious effects of mycoviruses are the ‘La France’ disease of Agaricus biporus[5][34] and the mushroom diseases caused by Oyster mushroom spherical virus[35] and Oyster mushroom isometric virus.[34]

In summary, the main negative effects of mycoviruses are:

- Decreased growth rate[36]

- Lack of sporulation[36]

- Attenuation of virulence[37]

- Reduced germination of basidiospores[38]

Hypovirulent phenotypes do not appear to correlate with specific genome features and it seems there is not one particular metabolic pathway causing hypovirulence but several.[39] In addition to negative effects, beneficial interactions do also occur. Well described examples are the killer phenotypes in yeasts[40] and Ustilago.[41] Killer isolates secrete proteins that are toxic to sensitive cells of the same or closely related species while the producing cells themselves are immune. Most of these toxins degrade the cell membrane.[40] There are potentially interesting applications of killer isolates in medicine, food industry, and agriculture.[20][40] A three-part system involving a mycovirus of an endophytic fungus (Curvularia protuberata) of the grass Dichanthelium lanuginosum has been described, which provides a thermal tolerance to the plant, enabling it to inhabit adverse environmental niches.[42]

Sources

- PhD thesis by Barbara Boine (2012): "A study of the interaction between the plant pathogenic fungus Botrytis cinerea and the filamentous ssRNA mycoviruses Botrytis virus X and Botrytis virus F. (The University of Auckland, School of Biological Sciences, Plant and Fungal Virology (Assoc. Prof. Mike Pearson); http://www.bioscienceresearch.co.nz/staff/mike-pearson/): https://researchspace.auckland.ac.nz/handle/2292/16777

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 Pearson, M. N.; Beever, R. E.; Boine, B.; Arthur, K. (2009). "Mycoviruses of filamentous fungi and their relevance to plant pathology". Molecular Plant Pathology. 10 (1): 115–128. doi:10.1111/j.1364-3703.2008.00503.x. PMID 19161358.

- 1 2 3 Bozarth, R. F. (1972). "Mycoviruses: a new dimension in microbiology". Environmental Health Perspectives. 2 (1): 23–39. doi:10.1289/ehp.720223. PMC 1474899

. PMID 4628853.

. PMID 4628853. - ↑ Göker, M.; Scheuner, C.; Klenk, H. P.; Stielow, J. B.; Menzel, W. (2011). "Codivergence of mycoviruses with their hosts". PLoS ONE. 6 (7): e22252. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0022252. PMC 3146478

. PMID 21829452.

. PMID 21829452. - 1 2 3 Ghabrial, S. A.; Suzuki, N. (2009). "Viruses of plant pathogenic fungi". Annual Review of Phytopathology. 47: 353–384. doi:10.1146/annurev-phyto-080508-081932. PMID 19400634.

- 1 2 Hollings, M. (1962). "Viruses Associated with A Die-Back Disease of Cultivated Mushroom". Nature. 196 (4858): 962–965. doi:10.1038/196962a0.

- ↑ Romaine, C. P.; Schlagnhaufer, B. (1995). "PCR analysis of the viral complex associated with La France disease of Agaricus bisporus". Applied and Environmental Microbiology. 61 (6): 2322–2325. PMC 167503

. PMID 7793952.

. PMID 7793952. - ↑ Anagnostakis, S. L.; Chen, B.; Geletka, L. M.; Nuss, D. L. (1998). "Hypovirus Transmission to Ascospore Progeny by Field-Released Transgenic Hypovirulent Strains of Cryphonectria parasitica". Phytopathology. 88 (7): 598–604. doi:10.1094/PHYTO.1998.88.7.598. PMID 18944931.

- ↑ Liu, Y. C.; Milgroom, M. G. (2007). "High diversity of vegetative compatibility types in Cryphonectria parasitica in Japan and China" (PDF). Mycologia. 99 (2): 279–284. doi:10.3852/mycologia.99.2.279. PMID 17682780.

- 1 2 Yu, X.; Li, B.; Fu, Y.; Jiang, D.; Ghabrial, S. A.; Li, G.; Peng, Y.; Xie, J.; Cheng, J.; Huang, J.; Yi, X. (2010). "A geminivirus-related DNA mycovirus that confers hypovirulence to a plant pathogenic fungus". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 107 (18): 8387–8392. doi:10.1073/pnas.0913535107. PMC 2889581

. PMID 20404139.

. PMID 20404139. - ↑ , King, A. M. Q., Lefkowitz E. M., Adams, J., Carstens, E. B. (2011). Virus Taxonomy: Ninth Report of the International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses (ICTV). San Diego, CA: Elsevier Academic.

- 1 2 3 Varga, J.; Tóth, B.; Vágvölgyi, C. (2003). "Recent advances in mycovirus research". Acta Microbiologica et Immunologica Hungarica. 50 (1): 77–94. doi:10.1556/AMicr.50.2003.1.8. PMID 12793203.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Ghabrial, S. A., Suzuki, N. (2008). Fungal Viruses. In B. W. J. Mahy and M. H. V. Van Regenmortel (ed.), Encyclopedia of Virology, 3rd ed., vol. 2. Elsevier, Oxford, United Kingdom. p. 284-291.

- ↑ Howitt, R. L.; Beever, R. E.; Pearson, M. N.; Forster, R. L. (2006). "Genome characterization of a flexuous rod-shaped mycovirus, Botrytis virus X, reveals high amino acid identity to genes from plant 'potex-like' viruses". Archives of Virology. 151 (3): 563–579. doi:10.1007/s00705-005-0621-y. PMID 16172841.

- ↑ Adams, M. J. (1991). "Transmission of plant viruses by fungi". Annals of Applied Biology. 118 (2): 479–492. doi:10.1111/j.1744-7348.1991.tb05649.x.

- ↑ Buck, K. W. (1986). Fungal Virology- An overview', in K. Buck (ed.), Fungal Virology (Boca Raton: CRC Press): 1-84.

- ↑ Deng, F.; Xu, R.; Boland, G. J. (2003). "Hypovirulence-Associated Double-Stranded RNA from Sclerotinia homoeocarpa Is Conspecific with Ophiostoma novo-ulmi Mitovirus 3a-Ld". Phytopathology. 93 (11): 1407–1414. doi:10.1094/PHYTO.2003.93.11.1407. PMID 18944069.

- ↑ Chen, B.; Choi, G. H.; Nuss, D. L. (1994). "Attenuation of fungal virulence by synthetic infectious hypovirus transcripts". Science. 264 (5166): 1762–1764. doi:10.1126/science.8209256. PMID 8209256.

- ↑ Forterre, P. (2006). "The origin of viruses and their possible roles in major evolutionary transitions". Virus Research. 117 (1): 5–16. doi:10.1016/j.virusres.2006.01.010. PMID 16476498.

- 1 2 Koonin, E. V.; Wolf, Y. I. (2008). "Genomics of bacteria and archaea: the emerging dynamic view of the prokaryotic world". Nucleic Acids Research. 36 (21): 6688–6719. doi:10.1093/nar/gkn668. PMC 2588523

. PMID 18948295.

. PMID 18948295. - 1 2 Dawe, A. L.; Nuss, D. L. (2001). "Hypoviruses and chestnut blight: exploiting viruses to understand and modulate fungal pathogenesis". 35: 1–29. doi:10.1146/annurev.genet.35.102401.085929. PMID 11700275.

- ↑ Fauquet, C. M., Mayo, M. A., Maniloff, J. (2005). Virus Taxonomy: Classification and Nomenclature of Viruses: The Eighth Report of the International Committee on the Taxonomy of Viruses. San Diego, CA: Elsevier Academic.

- ↑ Ghabrial, S. A. (1994). New Developments in Fungal Virology. In Frederick A. Murphy Karl Maramorosch and J. Shatkin Aaron (eds.), Advances in Virus Research (Volume 43: Academic Press): 303-388.

- ↑ Liu, H.; Fu, Y.; Jiang, D.; Li, G.; Xie, J.; Peng, Y.; Yi, X.; Ghabrial, S. A. (2009). "A novel mycovirus that is related to the human pathogen Hepatitis E virus and rubi-like viruses. Journal of Virology, 83 (4) 1981-1991". Phytopathology. 155 (2): 65–69.

- ↑ Liu, Y. C.; Linder-Basso, D.; Hillman, B. I.; Kaneko, S.; Milgroom, M. G. (2003). "Evidence for interspecies transmission of viruses in natural populations of filamentous fungi in the genus Cryphonectria". Molecular Ecology. 12 (6): 1619–1628. doi:10.1046/j.1365-294x.2003.01847.x.

- ↑ Melzer, M. S., Deng, F., Boland, G. J. (2005). Asymptomatic infection, and distribution of Ophiostoma mitovirus 3a (OMV3a), in populations of Sclerotinia homoeocarpa. Canadian Journal of Plant Pathology, 27 (4:, 610-615.

- ↑ Van Diepeningen, A. D., Debets, A. J. M., Slakhorst, S. M., Fekete, C., Hornok, L., Hoekstra, R. F. (2000). Interspecies virus transfer via protoplast fusions between Fusarium poae and black Aspergillus strains. Fungal Genetics Newsletter, 47: 99-100.

- 1 2 Van Diepeningen, A. D., Debets, A., and Hoekstra, R. (2006). Dynamics of dsRNA mycoviruses in black Aspergillus populations. Fungal Genetics and Biology, 43: 446-452.

- ↑ Sasaki, A.; Kanematsu, S.; Onoue, M.; Oyama, Y.; Yoshida, K. (2006). "Infection of Rosellinia necatrix with purified viral particles of a member of Partitiviridae (RnPV1-W8)". Archives of Virology. 151 (4): 697–707. doi:10.1007/s00705-005-0662-2. PMID 16307176.

- ↑ Vilches, S.; Castillo, A. (1997). "A double-stranded RNA mycovirus in Botrytis cinerea". FEMS Microbiology Letters. 155 (1): 125–130. doi:10.1016/S0378-1097(97)00377-7. PMID 9345772.

- ↑ Wu, M.; Zhang, L.; Li, G.; Jiang, D.; Ghabrial, S. A. (2010). "Genome characterization of a debilitation-associated mitovirus infecting the phytopathogenic fungus Botrytis cinerea". Virology. Elsevier. 406 (1): 117–126. doi:10.1016/j.virol.2010.07.010. PMID 20674953.

- ↑ McCabe, P. M.; Pfeiffer, P.; Van Alfen, N. K. (1999). "The influence of dsRNA viruses on the biology of plant pathogenic fungi". Trends in Microbiology. 7 (9): 377–381. doi:10.1016/S0966-842X(99)01568-1. PMID 10470047.

- ↑ May, R. M.; Nowak, M. A. (1995). "Coinfection and the evolution of parasite virulence" (PDF). Proceedings of the Royal Society B. 261 (1361): 209–215. doi:10.1098/rspb.1995.0138. PMID 7568274.

- ↑ Araújo, A., Jansen, A. M., Bouchet, F., Reinhard, K., Ferreira, L. F. (2003). Parasitism, the Diversity of Life, and Paleoparasitology. Memorias do Instituto Oswaldo Cruz, 98 (SUPPL. 1): 5-11.

- 1 2 Ro, H. S.; Lee, N. J.; Lee, C. W.; Lee, H. S. (2006). "Isolation of a novel mycovirus OMIV in Pleurotus ostreatus and its detection using a triple antibody sandwich-ELISA". Journal of Virological Methods. 138 (1-2): 24–29. doi:10.1016/j.jviromet.2006.07.016. PMID 16930731.

- ↑ Yu, H. J.; Lim, D.; Lee, H. S. (2003). "Characterization of a novel single-stranded RNA mycovirus in Pleurotus ostreatus". Virology. 314 (1): 9–15. doi:10.1016/S0042-6822(03)00382-9. PMID 14517055.

- 1 2 Moleleki, N.; van Heerden, S. W.; Wingfield, M. J.; Wingfield, B. D.; Preisig, O. (2003). "Transfection of Diaporthe perjuncta with Diaporthe RNA virus". Applied and Environmental Microbiology. 69 (7): 3952–3956. doi:10.1128/AEM.69.7.3952-3956.2003. PMC 165159

. PMID 12839766.

. PMID 12839766. - ↑ Suzaki, K.; Ikeda, K. I.; Sasaki, A.; Kanematsu, S.; Matsumoto, N.; Yoshida, K. (2005). "Horizontal transmission and host-virulence attenuation of totivirus in violet root rot fungus Helicobasidium mompa". Journal of General Plant Pathology. 71 (3): 161–168. doi:10.1007/s10327-005-0181-8.

- ↑ Ihrmark, K.; Stenström, E.; Stenlid, J. (2004). "Double-stranded RNA transmission through basidiospores of Heterobasidion annosum". Mycological Research. 108 (2): 149–153. doi:10.1017/S0953756203008839. PMID 15119351.

- ↑ Xie, J.; Wei, D.; Jiang, D.; Fu, Y.; Li, G.; Ghabrial, S.; Peng, Y. (2006). "Characterization of debilitation-associated mycovirus infecting the plant-pathogenic fungus Sclerotinia sclerotiorum". Journal of General Virology. 87 (1): 241–249. doi:10.1099/vir.0.81522-0. PMID 16361437.

- 1 2 3 Schmitt, M. J.; Breinig, F. (2002). "The viral killer system in yeast: from molecular biology to application". FEMS Microbiology Reviews. 26 (3): 257–276. doi:10.1016/S0168-6445(02)00099-2. PMID 12165427.

- ↑ Marquina, D.; Santos, A.; Peinado, J. M. (2002). "Biology of killer yeasts" (PDF). International Microbiology. 5 (2): 65–71. doi:10.1007/s10123-002-0066-z. PMID 12180782.

- ↑ Márquez, L. M.; Redman, R. S.; Rodriguez, R. J.; Roossinck, M. J. (2007). "A Virus in a Fungus in a Plant: Three-Way Symbiosis Required for Thermal Tolerance". Science. 315 (5811): 513–515. doi:10.1126/science.1136237. PMID 17255511.

External links

- International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses: http://www.ictvonline.org

- http://worldofmycoviruses.info/index.html

- The Second International Mycovirus Symposium:Mycoviruses: Virocontrol, neutralism and mutualism. http://www.rib.okayama-u.ac.jp/pmi/IMS%20II.html