Naming taboo

| Naming taboo | |||||||||||||

| Chinese name | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional Chinese | 避諱 | ||||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 避讳 | ||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||

| Vietnamese name | |||||||||||||

| Vietnamese alphabet | húy kỵ | ||||||||||||

| Hán-Nôm | 諱忌 | ||||||||||||

| Korean name | |||||||||||||

| Hangul | 피휘 | ||||||||||||

| Hanja | 避諱 | ||||||||||||

| Japanese name | |||||||||||||

| Kanji | 避諱 | ||||||||||||

| Hiragana | ひき | ||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||

A naming taboo is a cultural taboo against speaking or writing the given names of exalted persons in China and neighboring nations in the ancient Chinese cultural sphere.

Kinds of naming taboo

- The naming taboo of the state (国讳; 國諱) discouraged the use of the emperor's given name and those of his ancestors. For example, during the Qin Dynasty, Qin Shi Huang's given name Zheng (政) was avoided, and the first month of the year "Zheng Yue" (政月: the administrative month) was rewritten into "Zheng Yue" (正月: the upright month) and furthermore renamed as "Duan Yue" (端月: the proper/upright month). The character 正 was also pronounced with a different tone (zhèng to zhēng) to avoid any similarity. The strength of this taboo was reinforced by law; transgressors could expect serious punishment for writing an emperor's name without modifications. In 1777, Wang Xihou (王錫侯) in his dictionary criticized the Kangxi dictionary and wrote the Qianlong Emperor's name without leaving out any stroke as required. This disrespect resulted in his and his family's executions and confiscation of their property.[1] This type of naming taboo is no longer observed in modern China.

- The naming taboo of the clan (家讳; 家諱) discouraged the use of the names of one's own ancestors. Generally, ancestor names going back to seven generations were avoided. In diplomatic documents and letters between clans, each clan's naming taboos were observed.

- The naming taboo of the holinesses (圣人讳; 聖人諱) discouraged the use of the names of respected people. For example, writing Confucius' name was taboo during the Jin Dynasty.

Methods to avoid offence

There were three ways to avoid using a taboo character:

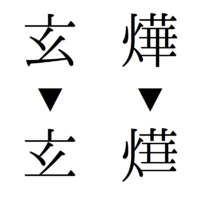

- Changing the character to another one which usually was a synonym or sounded like the character being avoided. For example, the Xuanwu Gate (玄武門: the Black Warrior Gate) of the Forbidden City was renamed as "Shenwu" (神武門: Gate of Divine Might) in order to avoid the Kangxi Emperor's name Xuanye (玄燁).

- Leaving the character as a blank.

- Omitting a stroke in the character, especially the final stroke.

Naming taboo in history

Throughout Chinese history, there were emperors whose names contained common characters who would try to alleviate the burden of the populace in practicing name avoidance. For example, Emperor Xuan of Han, whose given name Bingyi (病已) contained two very common characters, changed his name to Xun (詢), a far less common character, with the stated purpose of making it easier for his people to avoid using his name.[2] Similarly, Emperor Taizong of Tang, whose given name Shimin (世民) also contained two very common characters, ordered that name avoidance only required the avoidance of the characters Shi and Min in direct succession and that it did not require the avoidance of those characters in isolation. However, his son Emperor Gaozong of Tang effectively made this edict of Emperor Taizong ineffective after his death by requiring the complete avoidance of the characters Shi and Min, necessitating the chancellor Li Shiji to change his name to Li Ji.[3]

The custom of naming taboo had a built-in contradiction: without knowing what the emperors' names were one could hardly be expected to avoid them, so somehow the emperors' names had to be informally transmitted to the populace to allow them to learn them in order to avoid them. In one famous incident in 435, during the Northern Wei Dynasty, Goguryeo ambassadors made a formal request that the imperial government issue them a document containing the emperors' names so that they could avoid offending the emperor while submitting their king's petition. Emperor Taiwu of Northern Wei agreed and issued them such a document.[4] However, the mechanism of how the regular populace would be able to learn the emperors' names remained generally unclear throughout Chinese history.

Since every reign of every dynasty had its own naming taboos, the study of naming taboos can help date an ancient text.

In other countries

In Vietnam, the family name Hoàng (黄) was changed to Huỳnh in the South due to the naming taboo of Lord Nguyễn Hoàng's name. Similarly, the family name "Vũ" is known as "Võ" in the South.

Japan was also heavily influenced by the naming taboo. In modern Japan, it concerns only the Emperor of Japan, whom people only refer as Tennō Heika (天皇陛下, his Majesty the Emperor) or Kinjō Heika (今上陛下, his current Majesty). Ancient Japanese people had so much respect for this custom that historians forgot the actual names of many historical figures or even sometimes the correct pronunciation, as many Han characters have multiple pronunciations. For example, the son of Oda Nobunaga, Oda Nobukatsu, is often called Oda Nobuo; but it mainly concerns more ancient historical figures like Murasaki Shikibu, whose actual name may forever remain a mystery.

Many Aboriginal Australian cultures avoid the names of deceased persons, both verbally and in written language. For this reason, the names of many notable Aboriginal people were only recorded by Westerners and may have been incorrectly transliterated.

See also

- Imperial examination in Chinese mythology, example

- Names of God in Judaism, similar taboo

References

- ↑ Cary Academy: The Qing Glory Days

- ↑ Zizhi Tongjian, vol. 25.

- ↑ Zizhi Tongjian, vol. 199.

- ↑ Zizhi Tongjian, vol. 122.

Further reading

- 陳垣 (Chen Yuan),《史諱舉例》 (Examples of Taboos in History) - the pioneering work in the field, written during the early 20th century, numerous editions