Nanotoxicology

| Part of a series of articles on the |

| Impact of nanotechnology |

|---|

| Health |

| Environmental |

| Other topics |

|

| Part of a series of articles on |

| Nanotechnology |

|---|

| Impact and applications |

| Nanomaterials |

| Molecular self-assembly |

| Nanoelectronics |

| Nanometrology |

| Molecular nanotechnology |

|

Nanotoxicology is the study of the toxicity of nanomaterials. Because of quantum size effects and large surface area to volume ratio, nanomaterials have unique properties compared with their larger counterparts.

Nanotoxicology is a branch of bionanoscience which deals with the study and application of toxicity of nanomaterials.[1] Nanomaterials, even when made of inert elements like gold, become highly active at nanometer dimensions. Nanotoxicological studies are intended to determine whether and to what extent these properties may pose a threat to the environment and to human beings.[2] For instance, Diesel nanoparticles have been found to damage the cardiovascular system in a mouse model.[3]

Background

Nanotoxicology is a sub-specialty of particle toxicology. It addresses the toxicology of nanoparticles (particles <100 nm diameter) which appear to have toxicity effects that are unusual and not seen with larger particles. Nanoparticles can be divided into combustion-derived nanoparticles (like diesel soot), manufactured nanoparticles like carbon nanotubes and naturally occurring nanoparticles from volcanic eruptions, atmospheric chemistry etc. Typical nanoparticles that have been studied are titanium dioxide, alumina, zinc oxide, carbon black, and carbon nanotubes, and "nano-C60". Nanoparticles have much larger surface area to unit mass ratios which in some cases may lead to greater pro-inflammatory effects (in, for example, lung tissue). In addition, some nanoparticles seem to be able to translocate from their site of deposition to distant sites such as the blood and the brain. This has resulted in a sea-change in how particle toxicology is viewed- instead of being confined to the lungs, nanoparticle toxicologists study the brain, blood, liver, skin and gut.

Calls for tighter regulation of nanotechnology have arisen alongside a growing debate related to the human health and safety risks associated with nanotechnology.[4] From a large-scale literature review, Yaobo Ding et al. found that release of airborne engineered nanoparticles and associated worker exposure from various production and handling activities at different workplaces are very probable.[5] The Royal Society identifies the potential for nanoparticles to penetrate the skin, and recommends that the use of nanoparticles in cosmetics be conditional upon a favorable assessment by the relevant European Commission safety advisory committee. Andrew Maynard[6] also reports that ‘certain nanoparticles may move easily into sensitive lung tissues after inhalation, and cause damage that can lead to chronic breathing problems’. [7]

Carbon nanotubes – characterized by their microscopic size and incredible tensile strength – are frequently likened to asbestos, due to their needle-like fiber shape. In a recent study that introduced carbon nanotubes into the abdominal cavity of mice, results demonstrated that long thin carbon nanotubes showed the same effects as long thin asbestos fibers, raising concerns that exposure to carbon nanotubes may lead to pleural abnormalities such as mesothelioma (cancer of the lining of the lungs caused by exposure to asbestos).[8] Given these risks, effective and rigorous regulation has been called for to determine if, and under what circumstances, carbon nanotubes are manufactured, as well as ensuring their safe handling and disposal.[9]

The Woodrow Wilson Centre’s Project on Emerging Technologies conclude that there is insufficient funding for human health and safety research, and as a result there is currently limited understanding of the human health and safety risks associated with nanotechnology. While the US National Nanotechnology Initiative reports that around four percent (about $40 million) is dedicated to risk related research and development, the Woodrow Wilson Centre estimate that only around $11 million is actually directed towards risk related research. They argued in 2007 that it would be necessary to increase funding to a minimum of $50 million in the following two years so as to fill the gaps in knowledge in these areas.[10]

The potential for workplace exposure was highlighted by the 2004 Royal Society report[11] which recommended a review of existing regulations to assess and control workplace exposure to nanoparticles and nanotubes. The report expressed particular concern for the inhalation of large quantities of nanoparticles by workers involved in the manufacturing process.

Stakeholders concerned by the lack of a regulatory framework to assess and control risks associated with the release of nanoparticles and nanotubes have drawn parallels with bovine spongiform encephalopathy (‘mad cow’s disease'), thalidomide, genetically modified food,[12] nuclear energy, reproductive technologies, biotechnology, and asbestosis. In light of such concerns, the Canadian based ETC Group have called for a moratorium on nano-related research until comprehensive regulatory frameworks are developed that will ensure workplace safety.

Reactive oxygen species

For some types of particles, the smaller they are, the greater their surface area to volume ratio and the higher their chemical reactivity and biological activity. The greater chemical reactivity of nanomaterials can result in increased production of reactive oxygen species (ROS), including free radicals.[13] ROS production has been found in a diverse range of nanomaterials including carbon fullerenes, carbon nanotubes and nanoparticle metal oxides. ROS and free radical production is one of the primary mechanisms of nanoparticle toxicity; it may result in oxidative stress, inflammation, and consequent damage to proteins, membranes and DNA.[13]

Biodistribution

The extremely small size of nanomaterials also means that they much more readily gain entry into the human body than larger sized particles. How these nanoparticles behave inside the body is still a major question that needs to be resolved. The behavior of nanoparticles is a function of their size, shape and surface reactivity with the surrounding tissue. In principle, a large number of particles could overload the body's phagocytes, cells that ingest and destroy foreign matter, thereby triggering stress reactions that lead to inflammation and weaken the body’s defense against other pathogens. In addition to questions about what happens if non-degradable or slowly degradable nanoparticles accumulate in bodily organs, another concern is their potential interaction or interference with biological processes inside the body. Because of their large surface area, nanoparticles will, on exposure to tissue and fluids, immediately adsorb onto their surface some of the macromolecules they encounter. This may, for instance, affect the regulatory mechanisms of enzymes and other proteins.

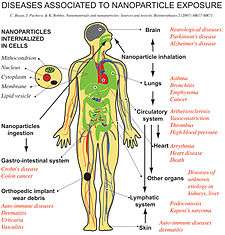

Nanomaterials are able to cross biological membranes and access cells, tissues and organs that larger-sized particles normally cannot.[14] Nanomaterials can gain access to the blood stream via inhalation[15] or ingestion.[16] At least some nanomaterials can penetrate the skin;[17] even larger microparticles may penetrate skin when it is flexed.[18] Broken skin is an ineffective particle barrier,[19] suggesting that acne, eczema, shaving wounds or severe sunburn may accelerate skin uptake of nanomaterials. Then, once in the blood stream, nanomaterials can be transported around the body and be taken up by organs and tissues, including the brain, heart, liver, kidneys, spleen, bone marrow and nervous system.[19] Nanomaterials have proved toxic to human tissue and cell cultures, resulting in increased oxidative stress, inflammatory cytokine production and cell death.[15] Unlike larger particles, nanomaterials may be taken up by cell mitochondria[20] and the cell nucleus.[21][22] Studies demonstrate the potential for nanomaterials to cause DNA mutation[22] and induce major structural damage to mitochondria, even resulting in cell death.[20][23]

Nanotoxicity studies

There is presently no authority to specifically regulate nanotech-based products. Scientific research has indicated the potential for some nanomaterials to be toxic to humans or the environment.[15][16] In March 2004 tests conducted by environmental toxicologist Eva Oberdörster, Ph.D. working with Southern Methodist University in Texas, found extensive brain damage to fish exposed to fullerenes for a period of just 48 hours at a relatively moderate dose of 0.5 parts per million (commensurate with levels of other kinds of pollution found in bays). The fish also exhibited changed gene markers in their livers, indicating their entire physiology was affected. In a concurrent test, the fullerenes killed water fleas, an important link in the marine food chain.[19] The extremely small size of fabricated nanomaterials also means that they are much more readily taken up by living tissue than presently known toxins. Nanoparticles can be inhaled, swallowed, absorbed through skin and deliberately or accidentally injected during medical procedures. They might be accidentally or inadvertently released from materials implanted into living tissue.

Researcher Shosaku Kashiwada of the National Institute for Environmental Studies in Tsukuba, Japan, in a more recent study, intended to further investigate the effects of nanoparticles on soft-bodied organisms. His study allowed him to explore the distribution of water-suspended fluorescent nanoparticles throughout the eggs and adult bodies of a species of fish, known as the see-through medaka (Oryzias latipes). See-through medaka were used because of their small size, wide temperature and salinity tolerances, and short generation time. Moreover, small fish like the see-through medaka have been popular test subjects for human diseases and organogenesis for other reasons as well, including their transparent embryos, rapid embryo development, and the functional equivalence of their organs and tissue material to that of mammals. Because the see-through medaka have transparent bodies, analyzing the deposition of fluorescent nanoparticles throughout the body is quite simple. For his study, Dr. Kashiwada evaluated four aspects of nanoparticle accumulation. These included the overall accumulation and the size-dependent accumulation of nanoparticles by medaka eggs, the effects of salinity on the aggregation of nanoparticles in solution and on their accumulation by medaka eggs, and the distribution of nanoparticles in the blood and organs of adult medaka. It was also noted that nanoparticles were in fact taken up into the bloodstream and deposited throughout the body. In the medaka eggs, there was a high accumulation of nanoparticles in the yolk; most often bioavailibility was dependent on specific sizes of the particles. Adult samples of medaka had accumulated nanoparticles in the gills, intestine, brain, testis, liver, and bloodstream. One major result from this study was the fact that salinity may have a large influence on the bioavailibility and toxicity of nanoparticles to penetrate membranes and eventually kill the specimen.[24]

As the use of nanomaterials increases worldwide, concerns for worker and user safety are mounting. To address such concerns, the Swedish Karolinska Institute conducted a study in which various nanoparticles were introduced to human lung epithelial cells. The results, released in 2008, showed that iron oxide nanoparticles caused little DNA damage and were non-toxic. Zinc oxide nanoparticles were slightly worse. Titanium dioxide caused only DNA damage. Carbon nanotubes caused DNA damage at low levels. Copper oxide was found to be the worst offender, and was the only nanomaterial identified by the researchers as a clear health risk.[25] The latest toxicology studies on mice involving exposure to carbon nanotubes (CNT) showed a limited pulmonary inflammatory potential of MWCNT at levels corresponding to the average inhalable elemental carbon concentrations observed in U.S.-based CNT facilities. The study estimated that considerable years of exposure are necessary for significant pathology to occur.[26]

No fullerene toxicity reported

Nanoparticles can also be made of C60, as is the case with almost any room temperature solid, and several groups have done this and studied toxicity of such particles. The results in the work of Oberdörster at Southern Methodist University, published in "Environmental Health Perspectives" in July 2004, in which questions were raised of potential cytotoxicity, has now been shown by several sources to be likely caused by the tetrahydrofuran used in preparing the 30 nm–100 nm particles of C60 used in the research. Isakovic, et al., 2006, who review this phenomenon, gives results showing that removal of THF from the C60 particles resulted in a loss of toxicity.[27] Sayes, et al., 2007, also show that particles prepared as in Oberdorster caused no detectable inflammatory response when instilled intratracheally in rats after observation for 3 months,[28] suggesting that even the particles prepared by Oberdorster do not exhibit markers of toxicity in mammalian models. This work used as a benchmark quartz particles, which did give an inflammatory response.

A comprehensive and recent review of work on fullerene toxicity is available in "Toxicity Studies of Fullerenes and Derivatives," a chapter from the book "Bio-applications of Nanoparticles".[29] In this work, the authors review the work on fullerene toxicity beginning in the early 1990s to present, and conclude that the evidence gathered since the discovery of fullerenes overwhelmingly points to C60 being non-toxic. As is the case for toxicity profile with any chemical modification of a structural moiety, the authors suggest that individual molecules be assessed individually.

Toxicity of Metal Based Nanoparticles

Metal based nanoparticles (NPs) are a prominent class of NPs synthesized for their functions as semiconductors, electroluminescents, and thermoelectric materials.[30] Biomedically, these antibacterial NPs have been utilized in drug delivery systems to access areas previously inaccessible to conventional medicine. With the recent increase in interest and development of nanotechnology, many studies have been performed to assess whether the unique characteristics of these NPs, namely their small surface area to volume ratio, might negatively impact the environment upon which they were introduced.[31] Researchers have since found that many metal and metal oxide NPs have detrimental effects on the cells with which they come into contact including but not limited to DNA breakage and oxidation, mutations, reduced cell viability, warped morphology, induced apoptosis and necrosis, and decreased proliferation.[30]

Cytotoxicity

A primary marker for the damaging effects of NPs has been cell viability as determined by state and exposed surface area of the cell membrane. Cells exposed to metallic NPs have, in the case of copper oxide, had up to 60% of their cells rendered unviable.[30] When diluted, the positively charged metal ions often experience an electrostatic attraction to the cell membrane of nearby cells, covering the membrane and preventing it from permeating the necessary fuels and wastes.[30] With less exposed membrane for transportation and communication, the cells are often rendered inactive.

NPs have been found to induce apoptosis in certain cells primarily due to the mitochondrial damage and oxidative stress brought on by the foreign NPs electrostatic reactions.[30]

Genotoxicity

Many methods ranging from comet assay to the HPRT gene mutation test have found that metal based NPs disrupt DNA and its replication process in a variety of cells. In a study examining the effects of nanosilver on DNA, AgNPs were introduced to lymphocyte cell DNA which was then examined for abnormalities. The exposure of the NPs correlated to a significant increase in micronuclei indicative of genetic fragmentation.[32] Metal Oxides such as copper oxide, uraninite, and cobalt oxide have also been found to exert significant stress on exposed DNA.[30] The damage done to the DNA will often result in mutated cells and colonies as found with the HPRT gene test.

Coatings and Charges

NPs, in their implementation, are covered with coatings and sometimes given positive or negative charges depending upon the intended function. Studies have found that these external factors affect the degree of toxicity of NPs.[33] Positive charges are usually found to amplify and cause of cellular damage much more noticeably than negative charges do. In a study in which b- and c-polyethylenimine coated AgNPs were attached to strands of Lambda DNA, the cationic b-polyethylenimine coated AgNP was found to lower the melting point of the DNA 50 °C lower than its anionic counterpart[29].

Immunogenicity of nanoparticles

Very little attention has been directed towards the potential immunogenicity of nanostructures. Nanostructures can activate the immune system, inducing inflammation, immune responses, allergy, or even affect to the immune cells in a deleterious or beneficial way (immunosuppression in autoimmune diseases, improving immune responses in vaccines). More studies are needed in order to know the potential deleterious or beneficial effects of nanostructures in the immune system. In comparison to conventional pharmaceutical agents, nanostructures have very large sizes, and immune cells, especially phagocytic cells, recognize and try to destroy them.

Complications with nanotoxicity studies

Size is therefore a key factor in determining the potential toxicity of a particle. However it is not the only important factor. Other properties of nanomaterials that influence toxicity include: chemical composition, shape, surface structure, surface charge, aggregation and solubility,[13] and the presence or absence of functional groups of other chemicals.[34] The large number of variables influencing toxicity means that it is difficult to generalise about health risks associated with exposure to nanomaterials – each new nanomaterial must be assessed individually and all material properties must be taken into account.

In addition, standarization of toxicology tests between laboratories are needed. Díaz, B. et al. from the University of Vigo (Spain) has shown (Small, 2008) that many different cell lines should be studied in order to know if a nanostructure induces toxicity, and human cells can internalize aggregated nanoparticles. Moreover, it is important to take into account that many nanostructures aggregate in biological fluids, but groups manufacturing nanostructures do not care much about this matter. Many efforts of interdisciplinary groups are strongly needed in order to progress in this field.

Effect of aggregation or agglomeration of nanoparticles

Many nanoparticles agglomerate or aggregate when they are placed in environmental or biological fluids.[35] The terms agglomeration and aggregation have distinct definitions according to the standards organizations ISO and ASTM, where agglomeration signifies more loosely bound particles and aggregation signifies very tightly bound or fused particles (typically occurring during synthesis or drying). Nanoparticles frequently agglomerate due to the high ionic strength of environmental and biological fluids, which shields the repulsion due to charges on the nanoparticles. Unfortunately, agglomeration has frequently been ignored in nanotoxicity studies, even though agglomeration would be expected to affect nanotoxicity since it changes the size, surface area, and sedimentation properties of the nanoparticles. In addition, many nanoparticles will agglomerate to some extent in the environment or in the body before they reach their target, so it is desirable to study how toxicity is affected by agglomeration.

A method was published that can be used to produce different mean sizes of stable agglomerates of several metal, metal oxide, and polymer nanoparticles in cell culture media for cell toxicity studies.[36] Different mean sizes of agglomerates are produced by allowing the nanoparticles to agglomerate to a particular size in cell culture media without protein, and then adding protein to coat the agglomerates and "freeze" them at that size. By waiting different amounts of time before adding protein, different mean sizes of agglomerates of a single type of nanoparticle can be produced in an otherwise identical solution, allowing one to study how agglomerate size affects toxicity. In addition, it was found that vortexing while adding a high concentration of nanoparticles to the cell culture media produces much less agglomerated nanoparticles than if the dispersed solution is only mixed after adding the nanoparticles.

The agglomeration/deagglomeration (mechanical stability) potentials of airborne engineered nanoparticle clusters also have significant influences on their size distribution profiles at the end-point of their environmental transport routes. Different aerosolization and deagglomeration systems have been established to test stability of nanoparticle agglomerates. For example, laboratory setups based on critical orifices have been used to apply a wide range of external shear forces onto airborne nanoparticles.[37] After applying shear forces, the particle mean size decreased while the particle generation rate increased. In another pioneering study, four powder aerosolization systems (dustiness testing systems) were compared for the first time for their characteristics linked to aerosol generation.[38]

Challenges of the nano-visualisation and related unknowns in nanotoxicology

With comparison to more conventional toxicology studies, the nanotoxicology field is however suffering from a lack of easy characterisation of the potential contaminants, the "nano" scale being a scale difficult to comprehend. The biological systems are themselves still not completely known at this scale. Ultimate Atomic visualisation methods such as Electron microscopy (SEM and TEM) and Atomic force microscopy (AFM) analysis allow visualisation of the nano world. Further nanotoxicology studies will require precise characterisation of the specificities of a given nano-element : size, chemical composition, detailed shape, level of aggregation, combination with other vectors, etc. Above all, these properties would have to be determined not only on the nanocomponent before its introduction in the living environment but also in the (mostly aqueous) biological environment.[39]

There is a need for new methodologies to quickly assess the presence and reactivity of nanoparticles in commercial, environmental, and biological samples since current detection techniques require expensive and complex analytical instrumentation. There have been recent attempts to address these issues by developing and investigating sensitive, simple and portable colorimetric detection assays that assess for the surface reactivity of NPs, which can be used to detect the presence of NPs, in environmental and biological relevant samples.[40] Surface redox reactivity is a key emerging property related to potential toxicity of NPs with living cells, and can be used as a key surrogate for determine for the presence of NPs and a first tier analytical strategy toward assessing NP exposures.

It is difficult to determine the degree of effect of a specific nanoparticle when compared to those of comparable nanoparticles already present in our natural environment .[41]

AEM - Analytical Electron Microscopy was used over 40 years ago to investigate amphibole asbestos bodies in Lake Superior from the Reserve Mining operations. This could non-destructively characterise sub-micron particles. Today AEM can fully characterise to atom dimensions.

See also

References

- ↑ Cristina Buzea, Ivan Pacheco, and Kevin Robbie "Nanomaterials and Nanoparticles: Sources and Toxicity" Biointerphases 2 (1007) MR17-MR71.

- ↑ Mahmoudi, Morteza; et al. (2012). "Assessing the In Vitro and In Vivo Toxicity of Superparamagnetic Iron Oxide Nanoparticles". Chemical Reviews. 112 (4): 2323–2338. doi:10.1021/cr2002596.

- ↑ http://www.bloomberg.com/apps/news?pid=washingtonstory&sid=aBt.yLf.YfOo study Pollution Particles Lead to Higher Heart Attack Risk (Update1)

- ↑ The Healthy Facilities Institute archive a document exploring the last 63 years of aerosol nanoparticle evaluation at their web site HERE - http://www.healthyfacilitiesinstitute.com/a_253-Commentary_What_You_Cant_See_Can_Still_Hurt_You

- ↑ Ding Y.; et al. (2016). "'Airborne engineered nanomaterials in the workplace—a review of release and worker exposure during nanomaterial production and handling processes". J. Hazard. Mater. doi:10.1016/j.jhazmat.2016.04.075.

- ↑ Andrew Maynard. "Nanotechnology: A Research Strategy for Addressing Risks": 310.

- ↑ Since 2005 a peer reviewed paper, cited by 1058, has remarked that silver nanoparticles are a bactericide and that this property is "only" size dependent, EPA reference - http://hero.epa.gov/index.cfm?action=reference.details&reference_id=196271

- ↑ Poland C, et al. (2008). "Carbon Nanotubes Introduced into the Abdominal Cavity of Mice Show Asbestos-Like Pathogenicity in a Pilot-Study". Nature Nanotechnology. 3 (7): 423–8. doi:10.1038/nnano.2008.111. PMID 18654567.

- ↑ Woodrow Wilson Centre for International Scholars Project on Emerging Nanotechnologies

- ↑ "An Issues Landscape for Nanotechnology Standards. Report of a Workshop" (PDF). Institute for Food and Agricultural Standards, Michigan State University, East Lansing. 2007.

- ↑ Royal Society and Royal Academy of Engineering (2004). "Nanoscience and nanotechnologies: opportunities and uncertainties". Retrieved 2008-05-18.

- ↑ Rowe G, Horlick-Jones T, Walls J, Pidgeon N (2005). "Difficulties in evaluating public engagement initiatives: reflections on an evaluation of the UK GM Nation?". Public Understanding of Science. 14 (4): 331–352. doi:10.1177/0963662505056611.

- 1 2 3 Nel, Andre; et al. (3 February 2006). "Toxic Potential of Materials at the Nanolevel". Science. 311 (5761): 622–7. doi:10.1126/science.1114397. PMID 16456071.

- ↑ Holsapple, Michael P.; et al. (2005). "Research Strategies for Safety Evaluation of Nanomaterials, Part II: Toxicological and Safety Evaluation of Nanomaterials, Current Challenges and Data Needs". Toxicological Sciences. 88 (1): 12–7. doi:10.1093/toxsci/kfi293. PMID 16120754.

- 1 2 3 Oberdörster, Günter; et al. (2005). "Principles for characterizing the potential human health effects from exposure to nanomaterials: elements of a screening strategy". Particle and Fibre Toxicology. 2: 8. doi:10.1186/1743-8977-2-8. PMC 1260029

. PMID 16209704.

. PMID 16209704. - 1 2 Hoet, Peter HM; et al. (2004). "Nanoparticles – known and unknown health risks". Journal of Nanobiotechnology. 2 (1): 12. doi:10.1186/1477-3155-2-12. PMC 544578

. PMID 15588280.

. PMID 15588280. - ↑ Ryman-Rasmussen, Jessica P.; et al. (2006). "Penetration of Intact Skin by Quantum Dots with Diverse Physicochemical Properties". Toxicological Sciences. 91 (1): 159–65. doi:10.1093/toxsci/kfj122. PMID 16443688.

- ↑ Tinkle, Sally S.; et al. (July 2003). "Skin as a Route of Exposure and Sensitization in Chronic Beryllium Disease". Environmental Health Perspectives. 111 (9): 1202–18. doi:10.1289/ehp.5999.

- 1 2 3 Oberdörster, Günter; et al. (July 2005). "Nanotoxicology: An Emerging Discipline Evolving from Studies of Ultrafine Particles". Environmental Health Perspectives. 113 (7): 823–39. doi:10.1289/ehp.7339. PMC 1257642

. PMID 16002369.

. PMID 16002369. - 1 2 Li N, Sioutas C, Cho A, et al. (Apr 2003). "Ultrafine particulate pollutants induce oxidative stress and mitochondrial damage". Environ Health Perspect. 111 (4): 455–60. doi:10.1289/ehp.6000. PMC 1241427

. PMID 12676598.

. PMID 12676598. - ↑ Porter, Alexandra E.; et al. (2007). "Visualizing the Uptake of C60 to the Cytoplasm and Nucleus of Human Monocyte-Derived Macrophage Cells Using Energy-Filtered Transmission Electron Microscopy and Electron Tomography". Environmental Science & Technology. 41 (8): 3012–7. doi:10.1021/es062541f.

- 1 2 Geiser, Marianne; et al. (November 2005). "Ultrafine Particles Cross Cellular Membranes by Nonphagocytic Mechanisms in Lungs and in Cultured Cells". Environmental Health Perspectives. 113 (11): 1555–60. doi:10.1289/ehp.8006. PMC 1310918

. PMID 16263511.

. PMID 16263511. - ↑ Savic, Radoslav; et al. (25 April 2003). "Micellar Nanocontainers Distribute to Defined Cytoplasmic Organelles". Science. 300 (5619): 615–8. doi:10.1126/science.1078192. PMID 12714738.

- ↑ Kashiwada S (Nov 2006). "Distribution of nanoparticles in the see-through medaka (Oryzias latipes)". Environ Health Perspect. 114 (11): 1697–702. doi:10.1289/ehp.9209. PMC 1665399

. PMID 17107855.

. PMID 17107855. - ↑ "Study Sizes up Nanomaterial Toxicity". Chemical & Engineering News. 86 (35). 1 Sep 2008.

- ↑ Aaron Erdely (Oct 2013). "Carbon nanotube dosimetry: from workplace exposure assessment to inhalation toxicology". Particle and Fibre Toxicology. 10.

- ↑ Isakovic A, Markovic Z, Nikolic N, et al. (Oct 2006). "Inactivation of nanocrystalline C60 cytotoxicity by gamma-irradiation". Biomaterials. 27 (29): 5049–58. doi:10.1016/j.biomaterials.2006.05.047. PMID 16784774.

- ↑ Sayes CM, Marchione AA, Reed KL, Warheit DB (2007). "Comparative Pulmonary Toxicity Assessments of C60 Water Suspensions in Rats: Few Differences in Fullerene Toxicity in Vivo in Contrast to in Vitro Profiles". Nano Lett. 7 (8): 2399–406. doi:10.1021/nl0710710. PMID 17630811.

- ↑ Chan WCW (2007). "Toxicity Studies of Fullerenes and Derivatives". Bio-applications of nanoparticles. New York, NY: Springer Science + Business Media. ISBN 0-387-76712-6.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Seabra, Amedea B.; Durán, Nelson (2015-06-03). "Nanotoxicology of Metal Oxide Nanoparticles". Metals. 5 (2): 934–975. doi:10.3390/met5020934.

- ↑ Schrand, Amanda M.; Rahman, Mohammad F.; Hussain, Saber M.; Schlager, John J.; Smith, David A.; Syed, Ali F. (2010-10-01). "Metal-based nanoparticles and their toxicity assessment". Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews. Nanomedicine and Nanobiotechnology. 2 (5): 544–568. doi:10.1002/wnan.103. ISSN 1939-0041. PMID 20681021.

- ↑ Huk, Anna; Izak-Nau, Emilia; Yamani, Naouale el; Uggerud, Hilde; Vadset, Marit; Zasonska, Beata; Duschl, Albert; Dusinska, Maria (2015-07-24). "Impact of nanosilver on various DNA lesions and HPRT gene mutations – effects of charge and surface coating". Particle and Fibre Toxicology. 12 (1). doi:10.1186/s12989-015-0100-x. PMC 4513976

. PMID 26204901.

. PMID 26204901. - ↑ Kim, Jeongeun; Chankeshwara, Sunay V.; Thielbeer, Frank; Jeong, Jiyoung; Donaldson, Ken; Bradley, Mark; Cho, Wan-Seob (2015-05-06). "Surface charge determines the lung inflammogenicity: A study with polystyrene nanoparticles". Nanotoxicology. 10: 1–8. doi:10.3109/17435390.2015.1022887. ISSN 1743-5404. PMID 25946036.

- ↑ Magrez, Arnaud; et al. (2006). "Cellular Toxicity of Carbon-Based Nanomaterials". Nano Letters. 6 (6): 1121–5. doi:10.1021/nl060162e. PMID 16771565.

- ↑ Bharti, Bhuvnesh; et al. (2011). "Aggregation of silica nanoparticles directed by adsorption of Lysozyme". Langmuir. 27: 9823–9833. doi:10.1021/la201898v. PMID 21728288.

- ↑ Zook, Justin; et al. (2011). "Stable nanoparticle aggregates/agglomerates of different sizes and the effect of their size on hemolytic cytotoxicity". Nanotoxicology. 5: 1–14. doi:10.3109/17435390.2010.536615. PMID 21142841.

- ↑ Ding Y., Riediker M. (2015). "'A System to Assess the Stability of Airborne Nanoparticle Agglomerates Under Aerodynamic Shear". J. Aerosol Sci. 88 (0): 98–108. doi:10.1016/j.jaerosci.2015.06.001.

- ↑ Ding Yaobo, Stahlmecke Burkhard, Sánchez Jiménez Araceli, Tuinman Ilse L., Kaminski Heinz, Kuhlbusch Thomas A. J., Martie , Riediker Michael (2015). "'Dustiness and Deagglomeration Testing: Interlaboratory Comparison of Systems for Nanoparticle Powders". Aerosol Science and Technology. 49 (12): 1222–1231. doi:10.1080/02786826.2015.1114999.

- ↑ http://www.nanosafe.org/scripts/home/publigen/content/templates/show.asp?P=63&L=EN&ITEMID=13

- ↑ Corredor, Charlie; Borysiak, Mark D.; Wolfer, Jay; Westerhoff, Paul; Posner, Jonathan D. (17 March 2015). "Colorimetric Detection of Catalytic Reactivity of Nanoparticles in Complex Matrices". Environmental Science & Technology. 49 (6): 3611–3618. doi:10.1021/es504350j.

- ↑ Mol. Cell. Neurosci. 31 (2006) 642 – 648

Further reading

- Donaldson K, Stone V, Tran CL, Kreyling W, Borm PJ (Sep 2004). "Nanotoxicology". Occup Environ Med. 61 (9): 727–8. doi:10.1136/oem.2004.013243. PMC 1763673

. PMID 15317911.

. PMID 15317911. - Singh S, Nalwa HS (Sep 2007). "Nanotechnology and health safety--toxicity and risk assessments of nanostructured materials on human health". J Nanosci Nanotechnol. 7 (9): 3048–70. doi:10.1166/jnn.2007.922. PMID 18019130.

- Lewinski N, Colvin V, Drezek R (Jan 2008). "Cytotoxicity of nanoparticles". Small. 4 (1): 26–49. doi:10.1002/smll.200700595. PMID 18165959.

- Suh WH, Suslick KS, Stucky GD, Suh YH (Feb 2009). "Nanotechnology, nanotoxicology, and neuroscience". Progress in Neurobiology. 87 (3): 133–170. doi:10.1016/j.pneurobio.2008.09.009. PMC 2728462

. PMID 18926873.

. PMID 18926873.

External links

- www.nanoobjects.info Acquisition, evaluation and public orientated presentation of societal relevant data and findings for nanomaterials (DaNa)

- Berger, Michael (2007-02-02). "Toxicology - from coal mines to nanotechnology". Nanowerk LLC. Retrieved 2007-05-15.

- The ICON Virtual Journal of Nanotechnology Environment, Health and Safety

- Colvin VL (Oct 2003). "The potential environmental impact of engineered nanomaterials". Nat. Biotechnol. 21 (10): 1166–70. doi:10.1038/nbt875. PMID 14520401.

- Yuliang Zhao; Hari Singh Nalwa (2007). Nanotoxicology: Interactions of Nanomaterials with Biological Systems. Los Angeles: American Scientific Publishers. ISBN 1-58883-088-8.

- Oberdörster G, Oberdörster E, Oberdörster J (Jul 2005). "Nanotoxicology: an emerging discipline evolving from studies of ultrafine particles". Environ. Health Perspect. 113 (7): 823–39. doi:10.1289/ehp.7339. PMC 1257642

. PMID 16002369.

. PMID 16002369. - Nel A, Xia T, Mädler L, Li N (Feb 2006). "Toxic potential of materials at the nanolevel". Science. 311 (5761): 622–7. doi:10.1126/science.1114397. PMID 16456071.

- Kurath M, Maasen S (2006). "Toxicology as a nanoscience?—disciplinary identities reconsidered". Part Fibre Toxicol. 3 (1): 6. doi:10.1186/1743-8977-3-6. PMC 1471800

. PMID 16646961.

. PMID 16646961. - Witzmann FA, Monteiro-Riviere NA (Sep 2006). "Multi-walled carbon nanotube exposure alters protein expression in human keratinocytes". Nanomedicine. 2 (3): 158–68. doi:10.1016/j.nano.2006.07.005. PMID 17292138.

- The International Council on Nanotechnology (ICON)

- The Center for Biological and Environmental Nanotechnology (CBEN), Rice University

- Nanotoxicity at Institute of Science in Society in London, UK

- Opportunities and Risks of Nanotechnology

- Oberdörstera E, Zhuc S, Blickleyb TM, McClellan-Greend P, Haaschc ML (May 2006). "Ecotoxicology of carbon-based engineered nanoparticles: Effects of fullerene (C60) on aquatic organisms". Carbon. 44 (6): 1112–20. doi:10.1016/j.carbon.2005.11.008.

- TITNT The International Team in NanoToxicology (TITNT) is an initiative of international research scientists interested in different aspects of the risk of toxicity associated to nanoparticles exposure. TITNT is composed of researchers from 5 different countries (Canada, USA, Japan, France and Germany) working together on 5 different specific thematic, and organized as 7 different platforms.

- Hoet PH, Brüske-Hohlfeld I, Salata OV (Dec 2004). "Nanoparticles – known and unknown health risks". J Nanobiotechnology. 2 (1): 12. doi:10.1186/1477-3155-2-12. PMC 544578

. PMID 15588280.

. PMID 15588280. - Ulrich Hottelet: Tiny particles, huge potential, German Times, December 2009