Minimal change disease

| Minimal change disease | |

|---|---|

| |

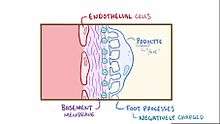

| The three hallmarks of minimal change disease: diffuse loss of podocyte foot processes, vacuolation, and the appearance of microvilli. | |

| Classification and external resources | |

| Specialty | urology |

| ICD-10 | N00-N08 with .0 suffix |

| ICD-9-CM | 581.3 |

| DiseasesDB | 8230 |

| MedlinePlus | 000496 |

| eMedicine | med/1483 |

Minimal change disease (also known as MCD and nil disease, among others) is a disease affecting the kidneys which causes a nephrotic syndrome. Nephrotic syndrome leads to the excretion of protein, which causes the widespread oedema (soft tissue swelling) and impaired kidney function commonly experienced by those affected by the disease. It is most common in children and has a peak incidence at 2 to 3 years of age[1]

Signs and symptoms

The clinical signs of minimal change disease are proteinuria (abnormal excretion of proteins, mainly albumin, into the urine), oedema (swelling of soft tissues as a consequence of water retention), and hypoalbuminaemia (low serum albumin). These signs are referred to collectively as nephrotic syndrome. Minimal change disease is unique among the causes of nephrotic syndrome as it lacks evidence of pathology in light microscopy, hence the name.

When albumin is excreted in the urine, its serum (blood) concentration decreases. Consequently, the intravascular oncotic pressure reduces relative to the interstitial tissue. The subsequent movement of fluid from the vascular compartment to the interstitial compartment manifests as the soft tissue swelling referred to as oedema. This fluid collects most commonly in the feet and legs, in response to gravity, particularly in those with poorly-functioning valves. In severe cases, fluid can shift into the peritoneal cavity (abdomen) and cause ascites. As a result of the excess fluid, individuals with minimal change disease often gain weight, as they are excreting less water in the urine, and experience fatigue. Additionally, the protein in the urine causes it to become frothy.

Pathophysiology

For years, pathologists found no changes when viewing specimens under light microscopy, hence the name "minimal change disease." With the advent of electron microscopy, the changes now known as the hallmarks for the disease were discovered. These are diffuse loss of visceral epithelial cells foot processes (i.e., podocyte effacement),[2] vacuolation, and growth of microvilli on the visceral epithelial cells.

The aetiology and pathogenesis of minimal change disease is unclear and is currently considered idiopathic. However, it does not appear to involve complement, immunoglobulins, or immune complex deposition. Rather, an altered cell-mediated immunologic response with abnormal secretion of lymphokines by T cells is thought to reduce the production of anions in the glomerular basement membrane, thereby increasing the glomerular permeability to serum albumin[3] through a reduction of electrostatic repulsion.[4] The loss of anionic charges is also thought to favor foot process fusion.[1] The etiological agent is unclear but viruses such as EBV and food allergies have been implicated. Also, the exact cytokine responsible has yet to be elucidated, with IL-12, IL-18 and IL-13 having been most studied in this regard, yet never conclusively implicated.

Genetics

Protein tyrosine phosphatase receptor type O, also known as glomerular epithelial protein 1 (GLEPP1), has been shown to be mutated in a number of cases.[5]

Treatment

Prednisone is prescribed along with a blood pressure medication, typically an ACE inhibitor such as lisinopril. Some nephrologists will start out with the ACE inhibitor first in an attempt to reduce the blood pressure's force which pushes the protein through the cell wall in order to lower the proteinuria. In some cases, a corticosteroid may not be necessary if the case of minimal change disease is mild enough to be treated just with the ACE inhibitor. Often, the liver is overactive with minimal change disease in an attempt to replace lost protein and over produces cholesterol. Therefore, a statin drug is often prescribed for the duration of the treatment. When the urine is clear of protein, the drugs can be discontinued. 50% of patients will relapse and need further treatment with immunosuppressants, such as cyclosporine and tacrolimus.

Minimal change disease usually responds well to initial treatment and over 90% of patients will respond to oral steroids within 6–8 weeks, with most of these having a complete remission.[6] Symptoms of nephrotic syndrome (NS) typically go away; but, this can take from 2 weeks to many months.[6] Younger children, who are more likely to develop minimal change disease, usually respond faster than adults. In 2 out of 3 children with minimal change disease; however, the symptoms of NS can recur, called a relapse, particularly after an infection or an allergic reaction. This is typical, and usually requires additional treatment. Many children experience 3 to 4 relapses before the disease starts to go away. Some children require longer term therapy to keep MCD under control. It appears that the more time one goes without a relapse, the better the chances are that a relapse will not occur. In most children with minimal change disease, particularly among those who respond typically, there is minimal to no permanent damage observed in their kidneys.

With steroid treatment, the symptoms of nephrotic syndrome (NS) will go away, called remission, in the majority of children with minimal change disease. This typically occurs faster, over 2 to 8 weeks, in younger children, but can take up to 3 or 4 months in adults. Typically, the dose of steroids will initially be fairly high, lasting 1or 2 months. When urine protein levels have normalised, steroids are gradually withdrawn over several weeks (to avoid triggering an Addisonian crisis). Giving steroids initially for a longer period of time is thought to reduce the likelihood of relapse. The majority of children with minimal change disease will respond to this treatment.

Even among those who respond well to steroids initially, it is common to observe periods of relapse (return of NS symptoms). 80% of those who get minimal change disease have a recurrence. Because of the potential for relapse, the physician may prescribe and teach the patient how to use a tool to have them check urine protein levels at home. Two out of 3 children who initially responded to steroids will experience this at least once. Typically the steroids will be restarted when this occurs, although the total duration of steroid treatment is usually shorter during relapses than it is during the initial treatment of the disease.

There are several immunosuppressive medications that can be added to steroids when the effect is not sufficient or replace them in case of intolerance or specific contraindications.

Epidemiology

Minimal change disease is most common in very young children but can occur in older children and adults. It is by far the most common cause of nephrotic syndrome (NS) in children between the ages of 1 and 7, accounting for the majority (about 90%) of these diagnoses.[7] Among teenagers who develop NS, it is caused by minimal change disease about half the time. It can also occur in adults but accounts for less than 20% of adults diagnosed with NS. Among children less than 10 years of age, boys seem to be more likely to develop minimal change disease than girls. Minimal change disease is being seen with increasing frequency in adults over the age of 80.

People with one or more autoimmune disorders are at increased risk of developing minimal change disease. Having minimal change disease also increases the chances of developing other autoimmune disorders.

Etymology

Minimal change disease has been called by many other names in the medical literature, including minimal change nephropathy, minimal change nephrosis, minimal change nephrotic syndrome, minimal change glomerulopathy, foot process disease (referring to the foot processes of the podocytes), nil disease (referring to the lack of pathologic findings on light microscopy), nil lesions, lipid nephrosis, and lipoid nephrosis.

References

- 1 2 Kumar V, Fausto N, Abbas A, eds. (2003). Robbins & Cotran Pathologic Basis of Disease (7th ed.). Saunders. pp. 981–2. ISBN 978-0-7216-0187-8.

- ↑ "Renal Pathology". Retrieved 2008-11-25.

- ↑ "Minimal_change_disease of the Kidney". Retrieved 2008-11-25.

- ↑ Mathieson P (2003). "Immune dysregulation in minimal change nephropathy". Nephrol Dial Transplant. 18 (Suppl 6): vi26–9. PMID 12953038.

- ↑ Ozaltin F, Ibsirlioglu T, Taskiran EZ, et al. (July 2011). "Disruption of PTPRO causes childhood-onset nephrotic syndrome". American Journal of Human Genetics. 89 (1): 139–47. doi:10.1016/j.ajhg.2011.05.026. PMC 3135805

. PMID 21722858.

. PMID 21722858. - 1 2 http://www.unckidneycenter.org/kidneyhealthlibrary/minimalchange.html

- ↑ Cameron JS (September 1987). "The nephrotic syndrome and its complications". Am. J. Kidney Dis. 10 (3): 157–71. doi:10.1016/s0272-6386(87)80170-1. PMID 3307394.

External links

- 355794967 at GPnotebook

- Kidcomm – An online resource for parents dealing with childhood kidney diseases

- National Kidney Foundation