White-eared honeyeater

| White-eared honeyeater | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Aves |

| Order: | Passeriformes |

| Family: | Meliphagidae |

| Genus: | Nesoptilotis |

| Species: | leucotis |

| Binomial name | |

| Nesoptilotis leucotis (Latham, 1801) | |

| Synonyms | |

|

Lichenostomus leucotis | |

.jpg)

.jpg)

The white-eared honeyeater (Nesoptilotis leucotis) is a medium-sized honeyeater found in eastern and western Australia. It is a member of the family Meliphagidae (honeyeaters and Australian chats) which has 182 recognised species with about half of them found in Australia. This makes them members of the most diverse family of birds in Australia. White-eared honeyeaters are easily identifiable by their olive-green body, black head and white ear patch.

Taxonomy

The white-eared honeyeater was first described by English ornithologist John Latham in 1801 as Turdus leucotis.[2][3] It has been reclassified several times and was previously named Lichenostomus leucotis and Ptilotis leucotis torringtoni.

The white-eared honeyeater was previously placed in the genus Lichenostomus but was moved to Nesoptilotis after a molecular phylogenetic analysis published in 2011 showed that the original genus was polyphyletic.[4][5] It is a sister taxon to the yellow-throated honeyeater (N. flavicollis) that occurs in Tasmania.[4]

Description

The white-eared honeyeater has an olive-green upper and lower body; its wings and tail are a mix of brown, yellow and olive; the crown is dark grey with black streaks; its cheeks, throat are black; its ear-coverts are white. Its iris is red or brown (juvenile); its bill is black and its legs are dark grey.[6] The white-eared honeyeater is a medium-sized honeyeater 19–22 cm tall.[7] There is no sexual dimorphism, with males and females looking alike.[8] They weigh approximately 20g [9] and have a beak length of approximately 17 mm long.[9]

Voice

Their voice is deep and mellow but slightly metallic chwok, chwok, chwok-whit and kwitchu, kwitchu; very sharply scratchy, metallic chwik!.[7]

Distribution and habitat

The white-eared honeyeater’s preferred habitat is in forests, woodlands, heathlands, mallee and dry inland scrublands.[7] A eucalyptus canopy, rough bark and a shrub layer are the most important requirements for white-eared honeyeaters. The canopy can provide nectar in spring, the bark can provide insects year round and the shrub layer is used for nesting and shelter.[10] The white-eared honeyeater prefers mature vegetation with a dense understory;.[11][12] They are relatively unselective regarding habitat, both floristically and structurally;[10][13] as they can be found in many different forest and woodland types, and edge or interior habitats.[14][15] White-eared honeyeaters can be found in small (< 2 ha) woodland patches.[16] Habitats they do not like are those that are heavily degraded,[11] recently burnt [17] or have little to no understory.

Races

There are three recognised races of N. leucotis. Race leucotis is found along eastern Australia from Victoria to central Queensland and the Eyre Peninsula in the west. It is proposed that this may be in fact two races, on either side of the Great Dividing Range. Evidence for this is that the populations on the eastern, coastal side of the Great Dividing Range have intense green upperparts, and light greenish-yellow on the belly, whereas, populations in the western, inland side of the Great Dividing Range are a duller olive colour and become a bit smaller. The Nullarbor Plain separates this race from the race novaenorciae which is found in Western Australia.[7] The western race novaenorciae is categorised as different due to size differences, with the western race being about 20% smaller than race leucotis.[10] Both populations look very similar but they have significant genetic differences. Populations of white-eared honeyeaters in Western Australia have significant genetic changes (2.23%) compared to eastern populations, however there are not any significant phenotype changes.[18] The third recognised race is thomasi. This race is found on Kangaroo Island in South Australia.

Populations of white-eared honeyeaters found in arid regions, Mallee and all populations of race novaenorciae do not need a shrub layer or understory.[10]

Behaviour

White-eared honeyeaters are usually solitary but may also be found in small family groups. They can be sedentary, nomadic or locally migratory.[7]

Breeding

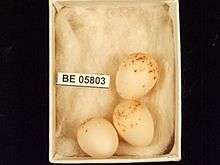

White-eared honeyeaters breed and nest from July to March. The nest is built among tangled twigs and leaves, low in a small shrub, bracken or coarse grass from 0.5 to 5 m high.[7] The cup shaped nest is constructed out of dry grass, fine stems, thin strips of bark and held together with cobwebs. The nest is lined with soft vegetation, down, feathers, hair or fur.[7] White-eared honeyeaters will pluck fur and hairs from livestock, humans and native wildlife such as kangaroos and wallabies.[6] White-eared honeyeaters form territories which can expand during winter when some key resources are in lower densities.[9][12] A clutch is typically 2 or 3 eggs. The eggs are oval shaped, white with brown speckles at the large end and are 21 x 15mm large.[7] A clutch is typically 2 or 3 eggs. The parents are obligate cooperative breeders of their chicks.[7][19]

The lifespan of the white-eared honeyeater is unknown, however many species of Australian honeyeaters (Meliphagidae) have an average lifespan of 10 – 15 years.[20] It is likely that the white-eared honeyeater is somewhere in this range.

Food and feeding

White-eared honeyeaters feed on nectar and insects.[21][22] White-eared honeyeaters are often considered nectivores but feed on insects just as much.[23] White-eared honeyeaters feed on nectar during the spring and summer (August - December) but would switch to insects the rest of the year.[9] White-eared honeyeaters actively probe for insects on tree trunks and branches.[9][10][23][24] White-eared honeyeaters prefer trees with soft, peeling and flaking bark where insects may be present.[10] They mostly collect mostly termites and spiders but will also feed on the lerp and honeydew produced by insects.[9] While foraging, the white-eared honeyeater searches intensively for its insect prey, it averages one insect every 5 seconds.[24] This high volume approach to foraging indicates that the insects being consumed are of low nutrition. Obligate nectivores compete strongly with white-eared honeyeaters for the best nectar resources and obligate insectivores compete with white-eared honeyeaters for best insect resources. This results in the white-eared honeyeater needing to utilise alternative sources of food, such as insects which are smaller or better at hiding.[10] Aggressive behaviour from the yellow-faced honeyeater (Lichenostomus chrysops) directed at the white-eared honeyeater has been observed.[25] The yellow-faced honeyeater has a similar feeding strategy to the white-eared honeyeater.

Status

Threats to the white-eared honeyeater are habitat degradation, fire and loss of understory.

References

- ↑ BirdLife International (2012). "Nesoptilotis leucotis". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Version 2013.2. International Union for Conservation of Nature. Retrieved 26 November 2013.

- ↑ Salomonsen, F. (1967). "Family Maliphagidae, Honeyeaters". In Paynter, R.A. Jnr. Check-list of birds of the world (Volume 12). Cambridge, Mass.: Museum of Comparative Zoology. p. 384.

- ↑ Latham, John (1801). Supplementum indicis ornithologici sive systematis ornithologiae (in Latin). London: Leigh & Sotheby. p. xliv.

- 1 2 Nyári, Á.S.; Joseph, L. (2011). "Systematic dismantlement of Lichenostomus improves the basis for understanding relationships within the honeyeaters (Meliphagidae) and historical development of Australo–Papuan bird communities". Emu. 111: 202–211. doi:10.1071/mu10047.

- ↑ Gill, Frank; Donsker, David (eds.). "Honeyeaters". World Bird List Version 6.1. International Ornithologists' Union. Retrieved 28 January 2016.

- 1 2 Officer, H.R. (1965). Australian Honeyeaters. melbourne: arbuckle, Waddell.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Morcombe, Michael (2012). Field Guide to Australian Birds, Vol. 8. Glebe: Pascal Press.

- ↑ Morcombe, M. (2012) Field Guide to Australian Birds Vol. 8. Pascal Press. Glebe, NSW.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Morris, W.J.; Wooller, R.D. (2001). "The structure and dynamics of an assemblage of small birds in a semi-arid eucalypt woodland in south-western Australia". Emu. 101: 7–12.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Pearce, J (1996). "Habitat Selection by the White-eared Honeyeater. 1. Review of Habitat Studies". Emu. 96: 42–49. doi:10.1071/mu9960042.

- 1 2 Barrett, G.W.; Ford, H.A.; Recher, H.F. (1994). "Conservation of woodland birds in a fragmented rural landscape". Pacific Conservation Biology. 1: 245–256.

- 1 2 Pearce, J; Minchin, P.R. (2001). "Vegetation of the Yellingbo Nature Conservation Reserve and its relationship to the distribution of the helmeted honeyeater, bell miner and white-eared honeyeater". Wildlife Research. 28: 41–52.

- ↑ Pearce, J.; Minchin, P.R. (2001). "Vegetation of the Yellingbo Nature Conservation Reserve and its relationship to the distribution of the helmeted honeyeater, bell miner and white-eared honeyeater". Wildlife Research. 28: 41–52.

- ↑ Baker, J.; French, K.; Whelan, R.J. (2002). "The edge effect and ecotonal species: bird communities across a natural edge in southeastern Australia". Ecology. 83 (11): 3048–3059. doi:10.1890/0012-9658(2002)083[3048:teeaes]2.0.co;2.

- ↑ Berry, L (2001). "Edge effects on the distribution and abundance of birds in a southern Victorian forest". Wildlife Research. 28: 239–245.

- ↑ Fischer, J.; Lindenmayer, D.B. (2002). "Small patches can be valuable for biodiversity conservation: two case studies on birds in southeastern Australia". Biological Conservation. 106: 129–136. doi:10.1016/s0006-3207(01)00241-5.

- ↑ Watson, S.J.; Taylor, R.S.; Nimmo, D.G.; Kelly, L.T.; Clarke, M.F; Bennett, A.F. (2012). "The influence of unburnt patches and distance from refuges on post-fire bird communities". Animal Conservation. 15: 499–507. doi:10.1111/j.1469-1795.2012.00542.x.

- ↑ Dolman, G; Joseph, L (2015). "Evolutionary history of birds across southern Australia: structure, history and taxonomic implications of mitochondrial DNA diversity in an ecologically diverse suite of species". Emu. 115: 35–48.

- ↑ Driskell, A.D.; Christidis, L. (2004). "Phylogeny and evolution of the Australo-Papuan honeyeaters (Passeriformes, Meliphagidae)". Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution. 31: 943–960. doi:10.1016/j.ympev.2003.10.017. PMID 15120392.

- ↑ Geering, David. "Longgevity of aust Birds". Birding Australia Mailing List Archives. Birding Aus. Retrieved 29 April 2015.

- ↑ Pyke, G.G.; Recher, H.F. (1987). "Seasonal Patterns of Capture Rate and Resource Abundance for Honeyeaters and Silvereyes in Heathland near Sydney". Emu. 88: 33–42. doi:10.1071/mu9880033.

- ↑ Allen, C.R.; Saunders, D.A. (2002). "Variability between Scales: Predictors of Nomadism in Birds of an Australian Mediterranean-Climate Ecosystem". Ecosystems. 5 (4): 348–359. doi:10.1007/s10021-001-0079-z.

- 1 2 Holmes, R.T.; Recher, H.F. (1986). "Search tactics of insectivorous birds foraging in an Australian eucalypt forest". The Auk. 103: 515–530.

- 1 2 Luck, G.W.; Possingham, H.P.; Paton, D.C. (1999). "Bird Responses at Inherent and Induced Edges in the Murray Mallee, South Australia. 1. Differences in Abundance and Diversity". Emu. 99: 157–169. doi:10.1071/mu99019.

- ↑ Clarke, M.F.; Schipper, C.; Boulton, R.; Ewen, J. (2003). "The social organization and breeding behaviour of the Yellow-faced Honeyeater Lichenostomus chrysops – a migratory passerine from the Southern Hemisphere". Ibis. 145: 611–623. doi:10.1046/j.1474-919x.2003.00203.x.