Neuropsychoanalysis

Neuropsychoanalysis (previously neuro-psychoanalysis) is a movement within neuroscience and psychoanalysis to combine the insights of both disciplines for a better understanding of mind and brain.

Theoretical Base: Dual Aspect Monism

Neuropsychoanalysis fits under the more general heading of neuropsychology: relating biological brain to psychological functions and behavior. Neuropsychoanalysis further seeks to remedy classical neurology's exclusion of the subjective mind.

Neuropsychology, like classical neurology, aims to be entirely objective, and its great power, its advances, come from just this. But a living creature, and especially a human being is first and last active—a subject, not an object. It is precisely the subject, the living "I," which is being excluded....What we need now, and need for the future, is a neurology of self, of identity.

Subjective mind, that is, sensations and thoughts and feelings and consciousness, seems a completely different thing from the cellular matter that gives rise to mind, so much so that Descartes concluded they were two entirely different kinds of stuff, mind and brain. Accordingly, he invented the "dualism" of the mind, the mind-body dichotomy. Body is one kind of thing, and mind (or spirit or soul) is another. But since this second kind of stuff does not lend itself to scientific inquiry, most of today's psychologists and neuroscientists have rejected Cartesian dualism.

They have had difficulty finding an alternative, however. The opposite position, monism, says there is only one kind of stuff, brain, and the sensations like the red of a tomato simply represent the pattern of activation of certain brain cells. Many people find this simple monism unsatisfactory, though, because it does not really deal with the fact that the red of a tomato and a pattern of activation in region V4 of the visual system seem so very different. Bridging that difference is what neuroscience calls "the hard problem."

Neuropsychoanalysis meets this challenge via dual-aspect monism, sometimes referred to as perspectivism. That is, we are monistic. Our brains, including mind, are made of one kind of stuff, cells, but we perceive this stuff in two different ways.[2]:56–58

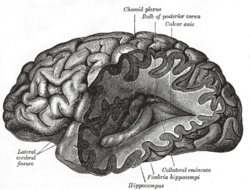

One is the neuroscientists' "objective" way. They dissect the brain with scalpel and microscope or look at it with brain scans and then trace neurochemical pathways. Neurology observes "mind" from outside, that is, by means of the neurological examination: questionnaires, the Boston Naming test or Wisconsin Sorting, bisecting lines, acting out how you use a screwdriver, and so on. Neurologists can compare the changes in psychological function that the neurological examination shows with the associated changes in the brain, either post mortem or by means of modern imaging technology.

The other way is the layman's or Descartes' or the psychoanalysts' way. We can observe "subjectively," from inside a mind, how we feel and what we think. Freud refined this kind of observation into free association. He claimed and a century of therapy confirms that this is the best technique that we have for perceiving complex mental functions that simple introspection will not reveal. Through psychoanalysis, we can discover mind's unconscious functioning.

Perhaps because Freud himself began his career as a neurologist, many of today's neurologists take psychoanalysis somewhat more seriously than, say, experimental psychologists do. As a result, the neuropsychoanalytic group has been able to draw useful insights from a number of distinguished neuroscientists: Antonio Damasio, Eric Kandel, Joseph LeDoux, Helen Mayberg, Jaak Panksepp, VS Ramachandran, Oliver Sacks, Mark Solms and many others. (Some serve on the editorial board of the journal Neuropsychoanalysis).

Research Directions

Neuropsychoanalytic researchers put these two kinds of knowledge together. They relate unconscious (and sometimes conscious) functioning discovered through the techniques of psychoanalysis or experimental psychology to underlying brain processes. Among the ideas explored in recent research are the following:

- "Consciousness" is limited (5-9 bits of information) compared to emotional and unconscious thinking based in the limbic system.[2] Note: Solm's book showed as reference in the footnote does not provide such an information. It may be confused with the capacity of short-term memory.

- Secondary-process, reality-oriented thinking can be understood as frontal lobe executive control systems.[2]

- Dreams, confabulations, and other expressions of primary-process thinking are meaningful, wish-fulfilling manifestations of the loss of frontal executive control of mesocortical and mesolimbic "seeking" systems.[2][3]

- Freud's "libido" corresponds to a dopaminergic seeking system[4]:144

- Drives can be understood as a series of basic emotions (prompts to action) anchored in pontine regions, specifically the periaqueductal gray, and projecting to cortex: play; seeking; caring; fear; anger; sadness. Seeking is constantly active; the others seek appropriate consummations (corresponding to Freud's "dynamic" unconscious).[4]

- Seemingly rational and conscious decisions are driven from the limbic system by emotions which are unconscious.[5]

- Infantile amnesia (the absence of memory for the first years of life) occurs because the verbal left hemisphere becomes activated later, in the second or third year of life, after the non-verbal right hemisphere. But infants can and do have procedural and emotional memories.[6][7]

- Infants' first-year experiences of attachment and second-year (approximately) experiences of disapproval lay down pathways that regulate emotions and profoundly affect adult personality.[6]

- Oedipal behaviors (observable in primates) can be understood as the effort to integrate lust systems (testosterone-driven), romantic love (dopamine-driven), and attachment (oxytocin-driven) in relation to key persons in the environment.[8]

- Differences between the sexes are more biologically-based and less environmentally-driven than Freud believed.[4]:225–260

References

- ↑ Sacks, Oliver (1998). "Understanding". A Leg to Stand On. Simon and Schuster. p. 177. ISBN 0-684-85395-7. Retrieved 2011-06-19.

- 1 2 3 4 Mark Solms; Oliver Turnbull (2002). The brain and the inner world: an introduction to the neuroscience of subjective experience. Other Press, LLC. ISBN 978-1-59051-017-9. Retrieved 2011-06-19.

- ↑ Karen Kaplan-Solms; Mark Solms (2001-11-17). Clinical Studies in Neuro-Psychoanalysis. Other Press, LLC. ISBN 978-1-59051-026-1. Retrieved 2011-06-19.

- 1 2 3 Jaak Panksepp (15 September 2004). Affective neuroscience: the foundations of human and animal emotions. Oxford University Press US. ISBN 978-0-19-517805-0. Retrieved 19 June 2011.

- ↑ Westen, Drew; Blagov, Pavel; Harenski, Keith; Kilts, Clint; Hamann, Stephan (2006). "Neural Bases of Motivated Reasoning: An fMRI Study of Emotional Constraints on Partisan Political Judgment in the 2004 U.S. Presidential Election" (PDF). Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience. 18 (11): 1947–1958. doi:10.1162/jocn.2006.18.11.1947. PMID 17069484. Retrieved 2011-06-19.

- 1 2 Schore, Allan (1999). Affect Regulation and the Origin of the Self: The Neurobiology of Emotional Development. Psychology Press. ISBN 978-0-8058-3459-8. Retrieved 2011-06-19.

- ↑ Schore, Allan (2001). "The effects of a secure attachment relationship on right brain development, affect regulation, and infant mental health" (PDF). Infant Mental Health Journal. 22 (1–2): 7–66. doi:10.1002/1097-0355(200101/04)22:1<7::AID-IMHJ2>3.0.CO;2-N. Retrieved 2011-06-19.

- ↑ Fisher, Helen (2004). Why we love: the nature and chemistry of romantic love. Macmillan. ISBN 978-0-8050-6913-6. Retrieved 2011-06-19.

External links

Online Sources

- International Neuropsychoanalysis Centre

- International Neuropsychoanalysis Society

- Neuropsychoanalysis, the journal

- Articles on neuropsychoanalysis and deep neuropsychology

Discussion

- Freud Returns? article criticizing Mark Solms's appeal to current neuroscientific research for vindicating Freudian theories; by Allen Esterson.

- An Interview with Mark Solms