Northanger Abbey

- For films named Northanger Abbey, see Northanger Abbey (1986 film) or Northanger Abbey (2007 film).

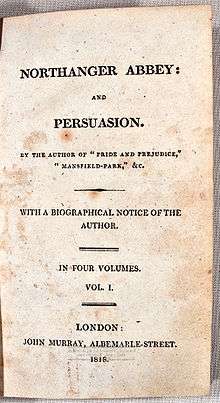

Title page of the original 1818 edition | |

| Author | Jane Austen |

|---|---|

| Country | United Kingdom |

| Language | English |

| Publisher | John Murray |

Publication date | December 1817 |

| Preceded by | Emma |

| Followed by | Persuasion |

Northanger Abbey /ˈnɔːrθˌæŋɡər/ was the first of Jane Austen's novels to be completed for publication, but published after her death, at the end of 1817. The novel is a satire of the Gothic novels popular at the time of its first writing in 1798–99. The heroine, Catherine, thinks life is like a Gothic novel, but her real experiences bring her down to earth as an ordinary young woman.

Austen first titled it Susan, when she sold it in 1803 for £10 to a London bookseller, Crosby & Co., who decided against publishing. In the spring of 1816, the bookseller sold it back to the novelist's brother, Henry Austen, for the same sum, as the bookseller did not know that the writer was by then the author of four popular novels. Austen further revised the novel in 1816-1817, with the intention of having it published. The lead character's name was changed from Susan to Catherine, and Austen changed the working title to Catherine.

Austen died in July 1817. Her brother Henry renamed the novel and arranged for publication of Northanger Abbey in late December 1817 (1818 given on the title page), as the first two volumes of a four-volume set; the other two volumes were the more recently completed Austen novel, Persuasion. Neither novel was published under the working title Jane Austen used. Aside from first being published together, the two novels are not linked, and later editions were published as separate novels.

The novel is more explicitly comic than her other works and contains many literary allusions that her parents and siblings would have enjoyed, as a family entertainment—a piece of lighthearted parody to be read aloud by the fireside. The novel names many of the Gothic novels of that time and includes direct commentary by Austen on the value of novels, which were not valued as much as nonfiction or historical fiction. As most all her letters were burned after her death, later scholars appreciate this insight into Austen's views.

Plot summary

Seventeen-year-old Catherine Morland is one of ten children of a country clergyman. Although a tomboy in her childhood, by the age of 17 she is "in training for a heroine" and is excessively fond of reading Gothic novels, among which Ann Radcliffe's Mysteries of Udolpho is a favourite.

Catherine is invited by the Allens, her wealthier neighbours in Fullerton, to accompany them to visit the town of Bath and partake in the winter season of balls, theatre and other social delights. Although initially the excitement of Bath is dampened by her lack of acquaintances, she is soon introduced to a clever young gentleman, Henry Tilney, with whom she dances and converses. Much to Catherine's disappointment, Henry does not reappear in the subsequent week and, not knowing whether or not he has left Bath for good, she wonders if she will ever see him again. Through Mrs Allen's old school-friend Mrs Thorpe, she meets her daughter Isabella, a vivacious and flirtatious young woman, and the two quickly become friends. Mrs Thorpe's son John is also a friend of Catherine's older brother, James, at Oxford where they are both students.

James and John arrive unexpectedly in Bath. While Isabella and James spend time together, Catherine becomes acquainted with John, a vain and crude young gentleman who incessantly tells fantastical stories about himself. Henry Tilney then returns to Bath, accompanied by his younger sister Eleanor, who is a sweet, elegant, and respectable young lady. Catherine also meets their father, the imposing General Tilney.

The Thorpes are not very happy about Catherine's friendship with the Tilneys, as they (correctly as it happens) perceive Henry as a rival for Catherine's affections. Catherine tries to maintain her friendships with both the Thorpes and the Tilneys, though John Thorpe continuously tries to sabotage her relationship with the Tilneys. This leads to several misunderstandings, which upset Catherine and put her in the awkward position of having to explain herself to the Tilneys.

Isabella and James become engaged. James's father approves of the match and offers his son a country parson's living of a modest sum, 400 pounds annually, which he may have in two and a half years. The couple must therefore wait until that time to marry. Isabella is dissatisfied, having believed that the Morlands were quite wealthy, but she pretends to Catherine that she is merely dissatisfied that they must wait so long. James departs to purchase a ring, and John accompanies him after coyly suggesting marriage to the oblivious Catherine. Isabella immediately begins to flirt with Captain Tilney, Henry's older brother. Innocent Catherine cannot understand her friend's behaviour, but Henry understands all too well, as he knows his brother's character and habits. The flirtation continues even when James returns, much to the latter's embarrassment and distress.

The Tilneys invite Catherine to stay with them for a few weeks at their home, Northanger Abbey. Catherine, in accordance with her novel reading, expects the abbey to be exotic and frightening. Henry teases her about this, as it turns out that Northanger Abbey is pleasant and decidedly not Gothic. However, the house includes a mysterious suite of rooms that no one ever enters; Catherine learns that they were Mrs Tilney's, who died nine years earlier. Catherine decides that, since General Tilney does not now seem to be affected by the loss of his wife, he may have murdered her or even imprisoned her in her chamber.

Catherine persuades Eleanor to show her Mrs Tilney's rooms, but General Tilney suddenly appears. Catherine flees, sure that she will be punished. Later, Catherine sneaks back to Mrs Tilney's rooms, to discover that her over-active imagination has once again led her astray, as nothing is strange or distressing in the rooms at all. Unfortunately, Henry joins her in the corridor and questions why she is there. He guesses her surmises and inferences, and informs her that his father loved his wife in his own way and was truly upset by her death. "What have you been judging from? Remember the country and the age in which we live. Remember that we are English, that we are Christians. Consult your own understanding, your own sense of the probable, your own observation of what is passing around you. Does our education prepare us for such atrocities? Do our laws connive at them? ... Dearest Miss Morland, what ideas have you been admitting?"[1] She leaves, crying, fearing that she has lost Henry's regard entirely.

Realizing how foolish she has been, Catherine comes to believe that, though novels may be delightful, their content does not relate to everyday life. Henry lets her get over her shameful thoughts and actions in her own time and does not mention them to her again.

Soon after this adventure, James writes to inform her that he has broken off his engagement to Isabella and that she has become engaged instead to Captain Tilney. Henry and Eleanor Tilney are shocked but rather skeptical that their brother has actually become engaged to Isabella Thorpe. Catherine is terribly disappointed, realising what a dishonest person Isabella is. A subsequent letter from Isabella herself confirms the Tilney siblings' doubts about the engagement and shows that Frederick Tilney was merely flirting with Isabella. The General goes off to London, and the atmosphere at Northanger Abbey immediately becomes lighter and pleasanter for his absence. Catherine passes several enjoyable days with Henry and Eleanor until, in Henry's absence, the General returns abruptly, in a temper. He forces Eleanor to tell Catherine that the family has an engagement that prevents Catherine from staying any longer and that she must go home early the next morning, in a shocking, inhospitable move that forces Catherine to undertake the 70 miles (110 km) journey alone.

At home, Catherine is listless and unhappy. Her parents, unaware of her trials of the heart, try to bring her up to her usual spirits, with little effect. Two days after she returns home, however, Henry pays a sudden unexpected visit and explains what happened. General Tilney (on the misinformation of John Thorpe) had believed her to be exceedingly rich and therefore a proper match for Henry. In London, General Tilney ran into Thorpe again, who, angry at Catherine's refusal of his half-made proposal of marriage, said instead that she was nearly destitute. Enraged, General Tilney returned home to evict Catherine. When Henry returned to Northanger from Woodston, his father informed him of what had occurred and forbade him to think of Catherine again. When Henry learns how she had been treated, he breaks with his father and tells Catherine he still wants to marry her despite his father's disapproval. Catherine is delighted.

Eventually, General Tilney acquiesces, because Eleanor has become engaged to a wealthy and titled man; and he discovers that the Morlands, while not extremely rich, are far from destitute.

Characters

Catherine Morland: A 17-year-old girl who loves reading Gothic novels. Something of a tomboy in her childhood, her looks are described by the narrator as "pleasing, and, when in good looks, pretty." Catherine lacks experience and sees her life as if she was a heroine in a Gothic novel. She sees the best in people, and to begin with always seems ignorant of other people's malign intentions. She is the devoted sister of James Morland. She is good-natured and frank and often makes insightful comments on the inconsistencies and insincerities of people around her, usually to Henry Tilney, and thus is unintentionally sarcastic and funny. (He is delighted when she says, "I cannot speak well enough to be unintelligible."[2]) She is also seen as a humble and modest character, becoming exceedingly happy when she receives the smallest compliment. Catherine's character grows throughout the novel, as she gradually becomes a real heroine, learning from her mistakes when she is exposed to the outside world in Bath. She sometimes makes the mistake of applying Gothic novels to real life situations; for example, later in the novel she begins to suspect General Tilney of having murdered his deceased wife. Catherine soon learns that Gothic novels are really just fiction and do not always correspond with reality.

James Morland: Catherine's older brother who is in school at the beginning of the story. Assumed to be of moderate wealth, he becomes the love interest of Isabella Thorpe, the younger sister to his friend and Catherine's admirer John Thorpe.

Henry Tilney: A 26-year-old well-read clergyman, the younger son of the wealthy Tilney family. He is Catherine's romantic interest throughout the novel, and during the course of the plot he comes to return her feelings. He is sarcastic, intuitive, fairly handsome and clever, given to witticisms and light flirtations (which Catherine is not always able to understand or reciprocate in kind), but he also has a sympathetic nature (he is a good brother to Eleanor), which leads him to take a liking to Catherine's naïve straightforward sincerity.

John Thorpe: An arrogant and extremely boastful young man who certainly appears distasteful to the likes of Catherine. He is Isabella's brother and he has shown many signs of feelings towards Catherine Morland.

Isabella Thorpe: A manipulative and self-serving young woman on a quest to obtain a well-off husband; at the time, marriage was the accepted way for young women of a certain class to become "established" with a household of their own (as opposed to becoming a dependent spinster), and Isabella lacks most assets (such as wealth or family connections to bring to a marriage) that would make her a "catch" on the "marriage market". Upon her arrival in Bath she is without acquaintance, leading her to immediately form a quick friendship with Catherine Morland. Additionally, when she learns that Catherine is the sister to James Morland (whom Isabella suspects to be worth more financially than he is in reality), she goes to every length to ensure a connection between the two families.

General Tilney: A stern and rigid retired general with an obsessive nature, General Tilney is the sole surviving parent to his three children Frederick, Henry, and Eleanor.

Eleanor Tilney: Henry's sister, she plays little part in Bath, but takes on more importance in Northanger Abbey. A convenient chaperon for Catherine and Henry's times together. Obedient daughter, warm friend, sweet sister, but lonely under her father's tyranny.

Frederick Tilney: Henry's older brother (the presumed heir to the Northanger estate), very handsome and fashionable, an officer in the army who enjoys pursuing flirtations with pretty girls who are willing to offer him some encouragement (though without any ultimate serious intent on his part).

Mr. Allen: A kindly man, with some slight resemblance to Mr. Bennet of Pride and Prejudice.

Mrs. Allen: Somewhat vacuous, she sees everything in terms of her obsession with clothing and fashion, and has a tendency to utter repetitions of remarks made by others in place of original conversation.

Major themes

- The intricacies and tedium of high society, particularly partner selection.

- The conflicts of marriage for love and marriage for property.

- Life lived as if in a Gothic novel, filled with danger and intrigue, and the obsession with all things Gothic.

- The dangers of believing life is the same as fiction.

- The maturation of the young into skeptical adulthood, the loss of imagination, innocence and good faith.

- Things are not what they seem at first.

- Social criticism (comedy of manners).

- Parody of the Gothic novels' "Gothic and anti-Gothic" attitudes.

In addition, Catherine Morland realizes she is not to rely upon others, such as Isabella, who are negatively influential on her, but to be single-minded and independent. It is only through bad experiences that Catherine really begins to mature and grow up.

Development

Austen first wrote this novel in 1798-1799 under the title Susan. She sold it to the publisher Crosby & Co. in 1803, but the publisher did nothing with it. After Austen's four anonymously published novels had success, her brother Henry bought the rights back for the same price in spring 1816. There was no increase in price as the bookseller was unaware it was an earlier book by a now successful author. Austen rewrote some sections, renaming the main character to Catherine, and using that as her working title.

Literary significance

Northanger Abbey is fundamentally a parody of Gothic fiction. Austen turns the conventions of eighteenth-century novels on their head, by making her heroine a plain and undistinguished girl from a middle-class family, allowing the heroine to fall in love with the hero before he has a serious thought of her, and exposing the heroine's romantic fears and curiosities as groundless. According to Austen biographer Claire Tomalin "there is very little trace of personal allusion the book, although it is written in the style of a family entertainment than any of the others".[3] Joan Aiken writes: "We can guess that Susan [the original title of Northanger Abbey], in its first outline, was written very much for family entertainment, addressed to a family audience, like all Jane Austen's juvenile works, with their asides to the reader, and absurd dedications; some of the juvenilia, we know, were specifically addressed to her brothers Charles and Frank; all were designed to be circulated and read by a large network of relations."[4]

Austen addresses the reader directly in parts, particularly at the end of Chapter 5, where she gives a lengthy opinion of the value of novels, and the contemporary social prejudice against them in favour of drier historical works and newspapers. In discussions featuring Isabella, the Thorpe sisters, Eleanor, and Henry, and by Catherine perusing the library of the General, and her mother's books on instructions on behaviours, the reader gains further insights into Austen's various perspectives on novels in contrast with other popular literature of the time (especially the Gothic novel). Eleanor even praises history books, and while Catherine points out the obvious fiction of the speeches given to important historical characters, Eleanor enjoys them for what they are.

The directness with which Austen addresses the reader, especially at the end of the story, gives a unique insight into Austen's thoughts at the time, which is particularly important due to the fact that a large portion of her letters were burned, at her request, by her sister upon her death.

A reviewer in 2016 said "Austen’s Northanger Abbey was in part a playful response to what she considered “unnatural” in the novels of her day: Instead of perfect heroes, heroines and villains, she offers flawed, rounded characters who behave naturally and not just according to the demands of the plot."[5]

Allusions to other works

Isabella: Dear creature! how much I am obliged to you; and when you have finished The Mysteries of Udolpho, we will read The Italian together; and I have made out a list of ten or twelve more of the same kind for you.

[...]

Catherine: ...but are they all horrid, are you sure they are all horrid?

Isabella: Yes, quite sure, for a particular friend of mine, a Miss Andrews, a sweet girl, one of the sweetest creatures in the world, has read every one of them.

Jane Austen, Northanger Abbey, chapter VI

Several Gothic novels and authors are mentioned in the book, including Fanny Burney and The Monk.[6] Isabella Thorpe gives Catherine a list of seven books that are commonly referred to as the "Northanger 'horrid' novels";[7] these works were initially thought to be of Austen's own invention until the British writers Montague Summers and Michael Sadleir found in the 1920s that they actually did exist.[8] The list is as follows:

- Castle of Wolfenbach (1793) by Eliza Parsons. London: Minerva Press.

- Clermont (1798) by Regina Maria Roche. London: Minerva Press.

- The Mysterious Warning, a German Tale (1796) by Eliza Parsons. London: Minerva Press.

- The Necromancer; or, The Tale of the Black Forest (1794) by 'Ludwig Flammenberg' (pseudonym for Carl Friedrich Kahlert; translated by Peter Teuthold). London: Minerva Press.

- The Midnight Bell (1798) by Francis Lathom. London: H. D. Symonds.

- The Orphan of the Rhine (1798) by Eleanor Sleath. London: Minerva Press.

- Horrid Mysteries (1796) by the Marquis de Grosse (translated by P. Will). London: Minerva Press.

All seven of these were republished by the Folio Society in London in the 1960s, and since 2005 Valancourt Books has released new editions of the 'horrids', the seventh and final being released in 2015.[9]

Historical source

The book contains an early reference to baseball.[10] It is found in the first chapter of the novel, describing the interest of the heroine : "...Catherine, who had by nature nothing heroic about her, should prefer cricket, baseball, riding on horseback, and running about the country...".[11] It is not the earliest reference to the term, which is presently believed to be in a 1744 British publication, A Little Pretty Pocket-Book, by John Newbery, as described in Origins of baseball. The modern game is not described, but the term is used.

References to Northanger Abbey

A passage from the novel appears as the preface of Ian McEwan's Atonement, thus likening the naive mistakes of Austen's Catherine Morland to those of his own character Briony Tallis, who is in a similar position: both characters have very over-active imaginations, which lead to misconceptions that cause distress in the lives of people around them. Both treat their own lives like those of heroines in fantastical works of fiction, with Miss Morland likening herself to a character in a Gothic novel and young Briony Tallis writing her own melodramatic stories and plays with central characters such as "spontaneous Arabella" based on herself.

Richard Adams quotes a portion of the novel's last sentence for the epigraph to Chapter 50 in his Watership Down; the reference to the General is felicitous, as the villain in Watership Down is also a General.[12]

Adaptations

Film, TV or theatrical adaptations

- The A&E Network and the BBC released the television adaptation Northanger Abbey in 1986.

- An adaptation of Northanger Abbey with screenplay by Andrew Davies, was shown on ITV on 25 March 2007 as part of their "Jane Austen Season". This adaptation aired on PBS in the United States as part of the "Complete Jane Austen" on Masterpiece Classic in January 2008. It stars Felicity Jones as Catherine Morland and JJ Feild as Henry Tilney.

- A stage adaptation of Northanger Abbey by Tim Luscombe (published by Nick Hern Books ISBN 9781854598370), was produced by Salisbury Playhouse in 2009. It was revived in Chicago in 2013 at the Remy Bumppo Theatre.[13]

- A theatrical adaptation by Michael Napier Brown was performed at the Royal Theatre in Northampton in 1998

- "Pup Fiction" – an episode of Wishbone featuring the plot and characters of Austen's Northanger Abbey.

Literature

HarperCollins hired Scottish crime writer Val McDermid in 2012 to adapt Northanger Abbey for a modern audience, as a suspenseful teen thriller, the second rewrite in The Austen Project.[14][15] McDermid said of the project, "At its heart it's a teen novel, and a satire – that's something which fits really well with contemporary fiction. And you can really feel a shiver of fear moving through it. I will be keeping the suspense – I know how to keep the reader on the edge of their seat. I think Jane Austen builds suspense well in a couple of places, but she squanders it, and she gets to the endgame too quickly. So I will be working on those things." The novel was published in 2014.[5][16][17]

See also

Reception history of Jane Austen

References

- ↑ Austen, Jane. "Chapter 24". Northanger Abbey. Project Gutenberg. Retrieved 4 August 2012.

- ↑ Austen, Jane. "Chapter 16". Northanger Abbey. Project Gutenberg. Retrieved 4 August 2012.

- ↑ Tomalin, Claire. Jane Austen: A Life. New York: Vintage, 1997, p. 165-166.

- ↑ Aiken, Joan (1985). "How Might Jane Austen Have Revised Northanger Abbey?". Persuasions, a publication of the Jane Austen Society of North America. Retrieved 4 August 2012.

- 1 2 Baker, Jo (13 June 2014). "It Was a Dark and Stormy Night: Val McDermid's 'Northanger Abbey'". New York Times. Retrieved 8 September 2016.

- ↑ Austen, Jane. "Chapter 7". Northanger Abbey. Project Gutenberg. Retrieved 4 August 2012.

- ↑ Ford, Susan Allen. "A Sweet Creature's Horrid Novels: Gothic Reading in Northanger Abbey". Jane Austen Society of North America. Retrieved 2016-04-22.

- ↑ Fincher, Max (March 22, 2011). "'I should like to spend my whole life in reading it': the resurrection of the Northanger 'horrid' novels". The Gothic Imagination (University of Sterling). Retrieved April 22, 2016.

- ↑ "About Jane Austen's Northanger Abbey 'Horrid Novels'". Valancourt Books. Retrieved 7 September 2014.

- ↑ Fornelli, Tom (6 November 2008). "Apparently Jane Austen Invented Baseball". AOL News.

- ↑ Austen, Jane. "Chapter 1". Northanger Abbey. Project Gutenberg. Retrieved 4 August 2012.

- ↑ Adams, Richard (1975). Watership Down. Avon. p. 470. ISBN 0-380-00293-0.

...[P]rofessing myself moreover convinced that the general's unjust interference, so far from being really injurious to their felicity, was perhaps rather conducive to it, by improving their knowledge of each other, and adding strength to their attachment, I leave it to be settled, by whomsoever it may concern...

- ↑ Weis, Hedi (8 October 2013). "Remy Bumppo's Northanger Abbey – a dazzling adaptation". Chicago Sun-Times. Retrieved 18 March 2014.

- ↑ "HarperCollins Announces New Fiction Imprint: The Borough Press". News Corp. 9 October 2013. Retrieved 8 September 2016.

- ↑ Flood, Alison (19 July 2012). "Jane Austen's Northanger Abbey to be reworked by Val McDermid". The Guardian. Retrieved 4 August 2012.

- ↑ McDermid, Val (2014). Northanger Abbey. The Borough Press. ISBN 978-0007504244.

- ↑ Forshaw, Barry (20 March 2014). "Northanger Abbey by Val McDermid, book review: A dark, daring adaptation - complete with social media and vampires". The Independent. Retrieved 7 September 2016.

External links

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

- Northanger Abbey at Project Gutenberg

-

Northanger Abbey public domain audiobook at LibriVox

Northanger Abbey public domain audiobook at LibriVox

_hires.jpg)

.jpg)