Frances Burney

- For the playwright Frances Burney (1776–1828), niece of the novelist, see Frances Burney.

| Frances Burney | |

|---|---|

|

Portrait by her relative Edward Francis Burney | |

| Born |

13 June 1752 Lynn Regis, England |

| Died |

6 January 1840 (aged 87) Bath, England |

| Notable works |

Journals (1768–1840) |

Frances Burney (13 June 1752 – 6 January 1840), also known as Fanny Burney and after her marriage as Madame d'Arblay, was an English satirical novelist, diarist and playwright. She was born in Lynn Regis, now King's Lynn, England, on 13 June 1752, to the musician and music historian Dr. Charles Burney (1726–1814) and his first wife, Esther Sleepe Burney (1725–1762). The third of six children, she was self-educated and began writing what she called her "scribblings" at the age of ten. In 1793, aged 41, she married a French exile, General Alexandre D'Arblay. Their only son, Alexander, was born in 1794. After a lengthy writing career, and travels during which she was stranded in France by warfare for more than ten years, she settled in Bath, England, where she died on 6 January 1840.

Overview of Burney's career

Frances Burney was a novelist, diarist and playwright. She wrote in all four novels, eight plays, one biography and twenty volumes of journals and letters. She has gained critical respect in her own right, but also foreshadows such novelists of manners with a satirical bent as Jane Austen and Thackeray. She published her first novel, Evelina, anonymously in 1778. When the book's authorship was revealed, it brought her almost immediate fame due to its unique narrative and comic strengths. She followed it with Cecilia in 1782, Camilla in 1796 and The Wanderer in 1814. All Burney's novels explore the lives of English aristocrats, and satirise their social pretensions and personal foibles, with an eye to larger questions such as the politics of female identity. With one exception, Burney never succeeded in having her plays performed, largely due to objections from her father, who thought that publicity from such an effort would be damaging to her reputation. The exception was Edwy and Elgiva, which unfortunately was not well received by the public and closed after the first night's performance.

Although her novels were hugely popular during her lifetime, Burney's reputation as a writer of fiction suffered after her death at the hands of biographers and critics who felt that the extensive diaries, published posthumously in 1841, offered a more interesting and accurate portrait of 18th-century life. Today critics are returning to her novels and plays with renewed interest in her outlook on the social lives and struggles of women in a predominantly male-oriented culture. Scholars continue to value Burney's diaries as well for their candid depictions of English society in her time.[1]

Throughout her career as a writer, her wit and talent for satirical caricature were widely acknowledged: literary figures such as Dr Samuel Johnson, Edmund Burke, Hester Thrale and David Garrick were among her admirers. Her early novels were read and enjoyed by Jane Austen, whose own title Pride and Prejudice derives from the final pages of Cecilia. William Makepeace Thackeray is reported to have drawn on the first-person account of the Battle of Waterloo, recorded in her diaries, while writing Vanity Fair.[2]

Frances Burney's early career was deeply affected by her relationship with her father, and by the critical attentions of their family friend Samuel Crisp. Both encouraged her writing, but also employed their influence in a critical fashion, dissuading her from publishing or performing her dramatic comedies because they felt that working in the genre was inappropriate for a lady. Many feminist critics thus see her as an author whose natural talent for satire was somewhat stifled by the social pressures exerted on female authors of the age.[3] But Burney persisted in writing despite the setbacks. When her comedies were poorly received, she returned to novel writing, and later tried her hand at tragedy. She supported both herself and her family with the proceeds of her later novels, Camilla and The Wanderer.

Family life

Frances was the third child in a family of six. Her elder siblings were Esther (Hetty) (1749–1832) and James (1750–1821), the younger Susanna Elizabeth (1755–1800), Charles (1757–1817) and Charlotte Ann (1761–1838). Of her brothers, James became an admiral and sailed with Captain James Cook on his second and third voyages. The younger Charles Burney became a well-known classical scholar. Her younger sister, Susanna, married in 1781 Molesworth Phillips, an officer in the Royal Marines who had sailed in Captain Cook's last expedition; she left a journal that is a principal eye-witness account of the Gordon Riots.[4] Her younger half-sister, Sarah Burney (1772–1844), also became a novelist, publishing seven works of fiction of her own.[5] Esther Sleepe Burney also bore two other boys, both named Charles, who died in infancy in 1752 and 1754.

Burney scholar Margaret Anne Doody[6] has investigated conflicts within the Burney family that affected Burney's writing and her personal life. Doody alleged that one strain was an incestuous relationship between her brother James and their half-sister Sarah in 1798–1803, but there is no direct evidence for this and it is hard to square with Frances's affection and financial assistance to Sarah in later life.[7]

Frances Burney’s mother, described by historians as a woman of “warmth and intelligence,” was the daughter of a French refugee named Dubois and had been brought up a Catholic. This French heritage influenced Frances Burney’s self-perception in later life, possibly contributing to her attraction and subsequent marriage to Alexandre D’Arblay. Esther Burney died when Frances was ten years old, in 1762, a loss which Frances felt throughout her life.[8]

Frances's father, Charles Burney, was noted for his personal charm, and even more for his talents as a musician, a musicologist, a composer and a man of letters.[5] In 1760 he moved his family to London, a decision that improved their access to the cultured elements of English society, and as a consequence their own social standing.[5] They lived in the midst of an artistically inclined social circle that gathered round Charles at their home in Poland Street in Soho.

In 1766 Charles Burney eloped to marry for a second time, to Elizabeth Allen, the wealthy widow of a King’s Lynn wine merchant. Allen had three children of her own, and several years after the marriage the two families merged into one. This new domestic situation was unfortunately fraught with tension. The Burney children found their new stepmother overbearing and quick to anger, and they took refuge from the situation by making fun of the woman behind her back. However, their collective unhappiness served in some respects to bring them closer to one another. In 1774 the family moved again to what had been the house of Isaac Newton in St Martin's Street, Westminster, London.

Education

Frances' sisters Esther and Susanna were favoured over Frances by their father, for what he perceived as their superior attractiveness and intelligence. At the age of eight, Frances had not yet learned the alphabet, and some scholars suggest that Burney suffered from a form of dyslexia.[9] By the age of ten, however, she had begun to write for her own amusement. Esther and Susanna were sent by their father to be educated in Paris, while at home Frances educated herself by reading from the family collection, including Plutarch's Lives, works by Shakespeare, histories, sermons, poetry, plays, novels and courtesy books.[10] She drew on this material, along with her journals, when writing her first novels. Scholars who have looked into the extent of Burney’s reading and self-education find a child who was unusually precocious and ambitious, working hard to overcome a childhood disability.[11]

A critical aspect of Frances's literary education was her relationship with a Burney family friend, the "cultivated littérateur" Samuel Crisp.[11] He encouraged Burney’s writing by soliciting frequent journal-letters from her that recounted to him the goings-on in her family and social circle in London. Frances paid her first formal visit to Crisp at Chessington Hall in Surrey in 1766. Dr Burney had first made Crisp's acquaintance in about 1745 at the house of Charles Cavendish Fulke Greville. Crisp's play Virginia, staged by David Garrick in 1754 at the request of the Countess of Coventry (née Maria Gunning), had been unsuccessful, and Crisp had retired to Chessington Hall, where he frequently entertained Dr Burney and his family.

Journal-diaries and The History of Caroline Evelyn

The first entry in her journal was made on 27 March 1768, addressed to "Miss Nobody". It was to extend over 72 years. A talented storyteller with a strong sense of character, Burney often wrote these "journal-diaries" as a form of correspondence with family and friends, recounting to them events from her life and her observations upon them. Her diary contains the record of her extensive reading in her father's library, as well the visits and behaviour of the various important arts personalities who came to their home. Frances and her sister Susanna were particularly close, and it was to this sister that Frances would correspond throughout her adult life, in the form of such journal-letters.

Burney was fifteen by the time her father remarried in 1767. Entries in her diaries suggest that she was beginning to feel pressure to give up her writing, as something "unladylike" that "might vex Mrs. Allen."[12] Feeling that she had transgressed what was proper, she burnt that same year her first manuscript, The History of Caroline Evelyn, which she had written in secret. Despite this repudiation of writing, Frances kept up her diaries and in them wrote an account of the emotions that led up to that dramatic act. She eventually recouped some of the effort that went into the first manuscript by using it as a foundation for her first novel, Evelina, which follows the life of the fictional Caroline Evelyn's daughter.

In keeping with this sense of impropriety that Burney felt towards her own writing, she savagely edited earlier parts of her diaries in later life, destroying much of the material. Editors Lars Troide and Joyce Hemlow recovered some of this obscured material while researching their late 20th-century editions of the journals and letters.

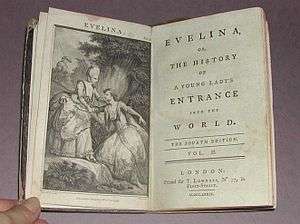

Evelina

Frances Burney's first novel, Evelina or the History of a Young Lady's Entrance into the World, was published anonymously in 1778, without her father's knowledge or permission, by Thomas Lowndes, who voiced his interest after reading its first volume and agreed to publish it upon receipt of the finished work. The novel had been rejected by a previous publisher, Robert Dodsley, who refused to print an anonymous work.[13] Burney, who worked as her father's amanuensis, had copied the manuscript in a "disguised hand" to prevent any identification of the book with the Burneys, thinking that her own handwriting might be recognised by a publisher. It was unthinkable at the time that a young woman would deliberately put herself into the public eye by writing, and Burney's second attempt to publish the work involved the collusion of her eldest brother, who posed as its author to Lowndes. Inexperienced at negotiating with a publisher, Burney only received twenty guineas as payment for the manuscript.

The novel was a critical success, receiving praise from respected individuals, including the statesman Edmund Burke and literary critic Dr Johnson.[11] It was admired for its comic view of wealthy English society, and for its realistic portrayal of working-class London dialects. It was even discussed by some characters in another epistolary novel of the period: Elizabeth Blower's The Parsonage House (1780).[14] Burney's father read public reviews of the novel before learning that the author was his own daughter. Although the act of publication was radical for a woman at that time and of her age, he was impressed by the favourable reactions to the book and largely supported her. Certainly, he saw social advantages to having a successful published writer in the family, and was pleased that Frances had achieved recognition through her work.[15]

Critical reception

Written in epistolary form, Evelina portrays the English upper middle class from the perspective of a 17-year-old woman who has reached marriageable age. A Bildungsroman ahead of its time, Evelina pushed boundaries since in the 18th century, female protagonists were "relatively rare" in that genre.[16] This comic and witty novel is ultimately a satire of the kind of oppressive masculine values that shaped a young woman's life in the 18th century, as well as of other forms of social hypocrisy.[5] Encyclopædia Britannica describes Evelina as a "landmark in the development of the novel of manners".[11]

In choosing to narrate the novel through a series of letters written by the protagonist, Burney made use of her own previous writing experience to recount the protagonist's views and experiences to the reader. This tactic has won praise from critics, past and present, for the direct access to events and characters that it allows to the reader, and for the narrative sophistication that it demonstrates in reversing the roles of narrator and heroine.[15] The authors of Women in World History argue that she draws attention to difficulties faced by women in the 18th century, especially those surrounding questions of romance and marriage.[15] She is described as a "shrewd observer of her times and a clever recorder of its charms and its follies". What critics have consistently found unique and interesting about her writing is the introduction and careful treatment of a female protagonist, complete with character flaws, "who must make her way in a hostile world." These are recognisable also as features of Jane Austen's writing, and show Burney's influence on the later author's work.[5]

As testament to its popularity, the novel went through four immediate editions. In 1971 it was still considered a classic by the writers of Encyclopædia Britannica, which stated that "addressed to the young, the novel has a quality perennially young."[13]

Hester Thrale and Streatham

The novel brought Frances Burney to the attention of patron of the arts Hester Thrale, who invited the young author to visit her home in Streatham. The house was a centre for literary and political conversation. Though shy by nature, Frances impressed those she met, including Dr Johnson, who would remain her friend and correspondent throughout the period of her visits, from 1779 to 1783. Mrs Thrale wrote to Dr Burney on 22 July, stating that: "Mr. Johnson returned home full of the Prayes of the Book I had lent him, and protesting that there were passages in it which might do honour to Richardson: we talk of it for ever, and he feels ardent after the dénouement; he could not get rid of the Rogue, he said." Dr Johnson's best compliments were eagerly transcribed in Frances's diary. Sojourns at Streatham occupied months at a time, and on several occasions the guests, including Frances Burney, made trips to Brighton and to Bath. As with other notable events, these experiences were recorded in letters to her family.[13]

The Witlings

In 1779, encouraged by the public's warm reception of comic material in Evelina, and with offers of help from Arthur Murphy and Richard Brinsley Sheridan, Burney began to write a dramatic comedy called The Witlings.

The play satirised a wide segment of London society, including the literary world and its pretensions. It was not published at the time because Burney's father and the family friend Samuel Crisp thought it would offend some of the public by seeming to mock the Bluestockings, and because they had reservations about the propriety of a woman writing comedy.[17] The play tells the story of Celia and Beaufort, lovers kept apart by their families due to "economic insufficiency".[15]

Burney's plays came to light again in 1945 when her papers were acquired by the Berg Collection of the New York Public Library.[18] A complete edition was published in Montreal in 1995, edited by Peter Sabor, Geoffrey Sill, and Stewart Cooke.[19]

Cecilia

In 1782 she published Cecilia, or Memoirs of an Heiress, written partly at Chessington Hall and after much discussion with Mr Crisp. The publishers, Thomas Payne and Thomas Cadell, paid Frances £250 for her novel, printed 2000 copies of the first edition, and reprinted it at least twice within a year.[20]

The plot of Cecilia revolves around the heroine, Cecilia Beverley, whose inheritance from her uncle comes with the stipulation that she find a husband who will accept her name. Beset on all sides by would-be suitors, the beautiful and intelligent Cecilia's heart is captivated by a man whose family's pride in its birth and ancestry would forbid the only son-and-heir's change of name. This young man finally persuades Cecilia, against all her good judgement, to agree to marry him secretly, so that their union – and, thus, the change of name – can be presented to the family as a fait accompli. The work received praise for the mature tone of its ironic third-person narration, but was viewed as less spontaneous than her first work, and as weighed down by the author's self-conscious awareness of her audience.[13] Some critics claim to have found the narration intrusive, while some of her friends found the writing too closely modelled on Johnson's.[15] Edmund Burke greatly admired the novel, but moderated his praise with a criticism of the enormous array of characters and tangled, convoluted plots.[13]

Jane Austen seems to have been inspired by a sentence in Cecilia to name her famous novel Pride and Prejudice: “The whole of this unfortunate business," said Dr Lyster, "has been the result of pride and prejudice.”

The Royal Court

In 1775 Frances Burney turned down a marriage proposal from one Thomas Barlow, a man whom she had met only once.[21] Her side of the Barlow courtship is amusingly told in her journal.[22] During the period 1782–85 she enjoyed the rewards of her successes as a novelist; she was received at fashionable literary gatherings throughout London. In 1781 Samuel Crisp died. In 1784 Dr Johnson died, and that year also saw the failure of her romance with a clergyman, George Owen Cambridge. She was 33 years old.

In 1785, thanks to her association with Mary Granville Delany, a woman known in both literary and royal circles, Frances travelled to the court of King George III and Queen Charlotte, where the Queen offered her the post of "Keeper of the Robes", with a salary of £200 per annum. Frances hesitated in taking the office, not wishing to be separated from her family, and especially resistant to any employment that would restrict the free use of her time in writing.[13] However, unmarried at 34, she felt constrained to accept and thought that improved social status and income might allow her greater freedom to write.[23] Having accepted the post in 1786, she developed a warm relationship with the queen and princesses that lasted into her later years, yet her anxieties proved to be accurate: the position exhausted her and left her little writing time. Her unhappiness was intensified by a poor relationship with her colleague Elizabeth Schwellenburg, co-Keeper of the Robes, who has been described as "a peevish old person of uncertain temper and impaired health, swaddled in the buckram of backstairs etiquette."[24]

During her years in court, Burney continued to produce her journals. To her friends and to Susanna, she recounted her life in court as well as significant political events, including the public trial of Warren Hastings for "official misconduct in India". She also recorded the speeches of Edmund Burke at the trial.[21] She was courted by an official of the royal household, Colonel Stephen Digby, but he eventually married another woman of greater wealth.[21] The disappointment, combined with the other frustrations of her office, contributed to her failing health at this time. In 1790 she prevailed on her father (whose own career had taken a new turn when he was appointed organist at Chelsea Hospital in 1783) to request that she be released from the post, which she was. She returned to her father's house in Chelsea, but continued to receive a yearly pension of £100. She maintained a friendship with the royal family and received letters from the princesses from 1818 until 1840.[13]

Marriage

In 1790–91 Burney wrote four blank-verse tragedies: Hubert de Vere, The Siege of Pevensey, Elberta and Edwy and Elgiva. Only the last was performed. Although it was one of a profusion of paintings and literary works about the early English king Eadwig to appear in the later 18th century, it met with public failure, opening in London in March for only one night.[25]

The French Revolution began in 1789 and Burney was among the many literate English figures who sympathized with its early ideals of equality and social justice.[26] During this period Frances became acquainted with a group of French exiles known as "Constitutionalists", who had fled to England in August 1791 and were living at Juniper Hall, near Mickleham, where Frances's sister Susanna lived. She quickly became close to General Alexandre D'Arblay, an artillery officer who had been adjutant-general to Lafayette, a hero of the French Revolution whose political views lay between those of Royalist and of Republicans. D'Arblay taught her French and introduced her to the writer Germaine de Staël.

Burney's father disapproved of the alliance because of Alexandre's poverty, his Catholicism, and his ambiguous social status as an émigré, but in spite of this they were married on 28 July 1793 In St Michaels and all Angels Church in Mickleham in Surrey. The same year she produced her pamphlet Brief Reflections relative to the Emigrant French Clergy. This short work was similar to other pamphlets produced by French sympathisers in England, calling for financial support for the revolutionary cause. It is noteworthy for the way that Burney employed her rhetorical skills in the name of tolerance and human compassion. On 18 December 1794, Frances gave birth to their son Alexander (died 19 January 1837). Her sister Charlotte's remarriage in 1798 to the pamphleteer Ralph Broome caused her and her father further consternation, as did the move by her sister Susanna and penurious brother-in-law Molesworth Phillips and their family to Ireland in 1796.

Camilla

The struggling young couple were saved from poverty in 1796 by the publication of Frances's "courtesy novel" Camilla, or a Picture of Youth, a story of frustrated love and impoverishment.[21] The first edition sold out; she made £1000 on the novel and sold the copyright for another £1000. This money was sufficient to allow them to build a house in Westhumble, which they called Camilla Cottage. Their life at this time was, by all accounts, a happy one, but the illness and death in 1800 of Frances's sister and close friend Susanna cast a shadow and brought to an end a lifelong correspondence that had been the motive and basis for most of Burney's journal writing. However, she resumed her journal writing at the request of her husband, for the benefit of her son.[27]

Comedies

In the period 1797–1801 Burney wrote three comedies that were not to be published in her lifetime: Love and Fashion, A Busy Day and The Woman Hater. The last is partly a reworking of subject-matter from The Witlings, but with the satirical elements toned down and more emphasis placed on reforming her characters' faults. The play, first performed in December 2007 at the Orange Tree Theatre in Richmond, UK, retains one of the central characters, Lady Smatter – an absent-minded but inveterate quoter of poetry, perhaps meant as a comic rendering of a Bluestocking. All the other characters in The Woman Hater differ from those in The Witlings.[28]

Life in France: revolution and mastectomy

In 1801 D'Arblay was offered service with the government of Napoleon Bonaparte in France, and in 1802 Burney and her son followed him to Paris, where they expected to remain for a year. The outbreak of the war between France and England overtook their visit, and they remained for ten years altogether. Although the conditions of their time in France left her isolated from her family, Burney was supportive of her husband's decision to move to Passy, outside Paris.

In August 1810 Burney developed pains in her breast, which her husband suspected could be due to breast cancer. Through her royal network of acquaintances she was eventually treated by several leading physicians and finally, a year later, on 30 September 1811, she underwent a mastectomy performed by "7 men in black, Dr. Larrey, M. Dubois, Dr. Moreau, Dr. Aumont, Dr. Ribe, & a pupil of Dr. Larrey, & another of M. Dubois". The operation was performed in the manner of a battlefield operation under the command of M. Dubois, then accoucheur (midwife or obstetrician) to the Empress Marie Louise, Duchess of Parma, and considered to be the best doctor in France. Burney was later able to describe the operation in detail, since she was conscious through most of it, as it took place before the development of anaesthetics.

I mounted, therefore, unbidden, the Bed stead – & M. Dubois placed me upon the Mattress, & spread a cambric handkerchief upon my face. It was transparent, however, & I saw, through it, that the Bed stead was instantly surrounded by the 7 men & my nurse. I refused to be held; but when, Bright through the cambric, I saw the glitter of polished Steel – I closed my Eyes. I would not trust to convulsive fear the sight of the terrible incision. Yet – when the dreadful steel was plunged into the breast – cutting through veins – arteries – flesh – nerves – I needed no injunctions not to restrain my cries. I began a scream that lasted unintermittingly during the whole time of the incision – & I almost marvel that it rings not in my Ears still? so excruciating was the agony. When the wound was made, & the instrument was withdrawn, the pain seemed undiminished, for the air that suddenly rushed into those delicate parts felt like a mass of minute but sharp & forked poniards, that were tearing the edges of the wound. I concluded the operation was over – Oh no! presently the terrible cutting was renewed – & worse than ever, to separate the bottom, the foundation of this dreadful gland from the parts to which it adhered – Again all description would be baffled – yet again all was not over, – Dr. Larry rested but his own hand, & – Oh heaven! – I then felt the knife (rack)ling against the breast bone – scraping it!

She sent her first-person account of this experience months later to her sister Esther without rereading it, and it remains one of the most compelling early accounts of a mastectomy.[29] It is impossible to know today whether the breast removed was indeed cancerous or whether she suffered from mastopathy. She survived and returned to England in 1812 to visit her ailing father and to avoid young Alexander's conscription into the French army, while still in recovery from her own illness.

Charles Burney died in 1814. In 1815 Napoleon escaped from Elba. D'Arblay was then serving with the King's Guard, and he became involved in the military actions that followed. After her father's death, Burney joined her wounded husband at Trèves (Trier), and together they returned to Bath in England. Burney wrote an account of this experience and of her Paris years in her Waterloo Journal, written between 1818 and 1832. D'Arblay was rewarded with promotion to lieutenant-general but died shortly afterwards of cancer, in 1818.

The Wanderer and Memoirs of Dr. Burney

Burney published her fourth novel, The Wanderer: Or, Female Difficulties, a few days before Charles Burney's death. Described as "a story of love and misalliance set in the French Revolution", it criticises the English treatment of foreigners during the war years.[1] It also pillories the hypocritical social curbs put on women in general – as the heroine tries one means after another to earn an honest penny – as well as the elaborate class criteria for social inclusion or exclusion. That strong social message sits uneasily within a strange structure that might be called a melodramatic proto-mystery novel with elements of the picaresque. The heroine is no scalliwag, in fact a bit too innocent for modern taste, but she is wilful and for obscure reasons refuses to reveal her name or origin. So as she darts about the South of England as a fugitive, she arouses suspicions that it is not always easy to agree with the author are unfair or unjustified. There are a dismaying number of coincidental meetings of characters.

Some parallels of plot and attitude have been drawn between The Wanderer and early novels of Helen Craik, which she could have read in the 1790s.[30]

Burney made £1500 from the first run, but the work disappointed her followers and it did not go into a second English printing, although it met her immediate financial needs. Critics felt it lacked the insight of her earlier novels.[1] It remains interesting today for the social opinions that it conveys and for some flashes of Burney's humour and discernment of character. It was reprinted with an introduction by the novelist Margaret Drabble in the "Mothers of the Novel" series.[31]

After her husband’s death, Burney moved to London to be nearer to her son, who was a fellow at Christ's College.[13] In homage to her father she gathered and in 1832 published, in three volumes, the Memoirs of Doctor Burney. The memoirs were written in a panegyric style, praising her father's accomplishments and character, and she cannibalised many of her own personal writings from years before to produce them. Always protective of her father and the family's reputation, she deliberately destroyed evidence of facts that were painful or unflattering, and was soundly criticised by her contemporaries and later by historians for doing so.[1] Otherwise, she lived essentially in retirement, outliving her son, who died in 1837, and her sister Charlotte Broome, who died in 1838. While in Bath, Burney received visits from younger members of the Burney family, who found her a fascinating storyteller with a talent for imitating the personalities that she described.[13] She continued to write often to members of her family.

Frances Burney died on 6 January 1840. She was buried with her son and her husband in Walcot cemetery in Bath. A gravestone was later erected in the churchyard of St Swithin's across the road. There is a Royal Society of Arts blue plaque to record her period of residence at 11 Bolton Street, Mayfair.[32]

List of works

| Library resources about Frances Burney |

| By Frances Burney |

|---|

Fiction

- The History of Caroline Evelyn, (ms. destroyed by author, 1767.)

- Evelina: Or The History of A Young Lady's Entrance into the World. London, 1778.

- Cecilia: Or, Memoirs of an Heiress. London, 1782.

- Camilla: Or, A Picture of Youth. London, 1796.

- The Wanderer: Or, Female Difficulties. London: Longmans, 1814.

Non-fiction

- Brief Reflections Relative to the French Emigrant Clergy. London, 1793.

- Memoirs of Doctor Burney. London: Moxon, 1832.

Journals and letters

- The Early Diary of Frances Burney 1768–1778. 2 vols. Ed. Annie Raine Ellis. London: 1889.

- The Diary and Letters of Madame D'Arblay. Ed. Austin Dobson. London: Macmillan, 1904.

- The Diary of Fanny Burney. Ed. Lewis Gibbs. London: Everyman, 1971.

- Dr. Johnson & Fanny Burney [HTML at Virginia], by Fanny Burney. Ed. Chauncy Brewster Tinker. London: Jonathan Cape, 1912.

- The Early Journals and Letters of Fanny Burney, 1768–1786. 5 vols. Vols. 1–2, ed. Lars Troide; Vol. 3, ed. Lars Troide and Stewart Cooke; Vol. 4, ed. Betty Rizzo; Vol. 5, ed. Lars Troide and Stewart Cooke.

- The Court Journals and Letters of Frances Burney. 4 vols. (to date). Vol. 1, 1786, ed. Peter Sabor; Vol. 2, 1787, ed. Stewart Cooke; Vols. 3 & 4, 1788, ed. Lorna Clark.

- The Journals and Letters of Fanny Burney (Madame D'Arblay) 1791–1840, (12 vols.) Vols. I–VI, ed. Joyce Hemlow, with Patricia Boutilier and Althea Douglas; Vol. VII, ed. Edward A. and Lillian D. Bloom; Vol. VIII, ed. Peter Hughes; Vols. IX-X, ed. Warren Derry; Vols. XI–XII, ed. Joyce Hemlow with Althea Douglas and Patricia Hawkins. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1972–84.

Plays

- The Witlings, 1779 (satirical comedy).

- Edwy and Elgiva, 1790 (verse tragedy). Produced at Drury Lane, 21 March 1795.

- Hubert de Vere, 1788–91? (verse tragedy).

- The Siege of Pevensey, 1788–91? (verse tragedy).

- Elberta, (fragment) 1788–91? (verse tragedy).

- Love and Fashion, 1799 (satirical comedy).

- The Woman Hater, 1800–1801 (satirical comedy).

- A Busy Day, 1800–1801 (satirical comedy).

Notes

- 1 2 3 4 Commire, Klezmer 231.

- ↑ Biography of Frances Burney

- ↑ Commire, Anne and Deborah Klezmer. Women in World History: a biographical encyclopedia. (Waterford: Yorkin Publications, 1999–2002) 231.

- ↑ Olleson, Philip, The Journals and Letters of Susan Burney: Music and Society in Late Eighteenth-Century England. Ashgate, 2012. ISBN 978-0-7546-5592-3

- 1 2 3 4 5 Commire, Klezmer 228.

- ↑ Frances Burney: The Life in The Works (New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press 1988), p. 277 ff.

- ↑ Lorna J. Clark, "Introduction", p. xii. In: Sarah Burney: The Romance of Private Life, ed. Lorna J. Clark (London: Pickering & Chatto, 2008. ISBN 1-85196-873-3).

- ↑ Doody 11.

- ↑ Julia Epstein,The Iron Pen: Frances Burney and the Politics of Women’s Writing.(Wisconsin: University of Wisconsin Press, 1989) 23.

- ↑ Encyclopædia Britannica, Vol. 4 (Chicago, London: Encyclopædia Britannica Inc., 1971) 450.

- 1 2 3 4 Encyclopædia Britannica 450.

- ↑ Doody 36.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Encyclopædia Britannica 451.

- ↑ Jacqueline Pearson: "Mothering the Novel. Frances Burney and the Next Generations of Women Novelists". CW3 Journal Retrieved 20 September 2015

- 1 2 3 4 5 Commire, Klezmer 229.

- ↑ Doody 45.

- ↑ Doody 451.

- ↑ Orange Tree Theatre, Richmond, Surrey: programme notes by the director Sam Walters for his world premiere production of The Woman Hater 19 December 2007

- ↑ The Complete Plays of Frances Burney. Vol. 1, Comedies; Vol. 2, Tragedies (McGill-Queen's University Press, Montreal, 1995). ISBN 0-7735-1333-7

- ↑ Journal entry of Charlotte Ann Burney, 15 January, [1783]. In: The Early Diary of Frances Burney 1768–1778, ed. Annie Raine Ellis (London: G. Bell and Sons Ltd., 1913 [1889]), p. 307.

- 1 2 3 4 Commire, Klezmer 230.

- ↑ The Early Diary of Frances Burney 1768–1778..., Vol. II, pp. 48 ff.

- ↑ Literature Online 2.

- ↑ Austin Dobson, Fanny Burney (Madame d'Arblay) (London: Macmillan, 1903), pp. 149–50.

- ↑ Encyclopædia Britannica 451; ODNB entry for Eadwig: Retrieved 18 August 2011. Subscription required.

- ↑ Commire, Klezmer, 231.

- ↑ Encyclopædia Britannica 452.

- ↑ The Witlings and The Woman-Hater, plays by Fanny Burney; ed Peter Sabor and Geoffrey Sill, Broadview Press (2002) ISBN 1-55111-378-3

- ↑ Frances Burney letter 22 March 1812, in the Henry W. and Albert A. Berg Collection, New York Public Library, New York.

- ↑ Adriana Craciun and Kari Lokke, eds: Rebellious Hearts. British Women Writers and the French Revolution (Albany, NY: State University of New York Press, 2001), p. 222 Retrieved 19 July 2015.

- ↑ Fanny Burney: The Wanderer or, Female Difficulties. (London: Pandora Press, 1988). ISBN 0-86358-263-X

- ↑ "BURNEY, FANNY (1752–1840)". English Heritage. Retrieved 23 October 2012.

References

- Adelstein, Michael E. Fanny Burney. New York: Twayne, 1968.

- Burney, Fanny. The Complete Plays of Frances Burney (Vol. 1: Comedies; Vol. 2: Tragedies), ed. Peter Sabor, Stewart Cooke, and Geoffrey Sill, Montreal: McGill-Queen's University Press, 1995. ISBN 0-7735-1333-7

- Burney, Fanny. The Witlings and The Woman-Hater. Ed. Peter Sabor and Geoffrey Sill, Peterborough: Broadview Press, 2002.

- “Burney, Fanny, 1752–1840.” Literature Online Biography. Fredericton: University of New Brunswick. 3 December 2006.

- "Burney, Fanny." Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 4, 1971.

- "Burney, Fanny." The Bloomsbury Guide to Women’s Literature. Ed. Claire Buck. London, New York: Prentice-Hall, 1992.

- Commire, Anne, and Deborah Klezmer. Women in World History: A biographical encyclopaedia. Waterford: Yorkin, 1999–2002.

- Devlin, D.D. The Novels and Journals of Frances Burney. Hampshire: Macmillan, 1987.

- D'Ezio, Marianna. "Transcending National Identity: Paris and London in Frances Burney’s Novels". Synergies Royaume-Uni et Irlande 3 (2010), 59–74.

- Doody, Margaret Anne. Frances Burney: The Life in The Works. New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press, 1988.

- Epstein, Julia. The Iron Pen: Frances Burney and the Politics of Women’s Writing. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 1989.

- Harman, Claire. Fanny Burney: A Biography. New York: Knopf, 2001.

- Hemlow, Joyce. The History of Fanny Burney. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1958.

- Simons, Judy. Diaries and Journals of Literary Women from Fanny Burney to Virginia Woolf. Hampshire: Macmillan, 1990.

- Stepankowsky, Paula. “Frances Burney d”Arblay”.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Fanny Burney. |

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Frances Burney |

| Wikisource has original works written by or about: Frances Burney |

- Works by Fanny Burney at A Celebration of Women Writers

- A Resource for Fanny Burney at FannyBurney.org

- Works by Fanny Burney at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about Fanny Burney at Internet Archive

- Works by Frances Burney at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

- Essays by Fanny Burney at Quotidiana.org

- Fanny Burney's own account of the mastectomy she underwent in 1811

- Burney Centre at McGill University

- The Burney Society

- Archival material relating to Frances Burney listed at the UK National Register of Archives

- Frances d'Arblay ('Fanny Burney') at the National Portrait Gallery, London

_by_Edward_Francisco_Burney.jpg)