O Come, All Ye Faithful

| O Come, All Ye Faithful | |

|---|---|

| |

| Native name | Adeste Fideles |

| Genre | Christmas |

| Language | Latin |

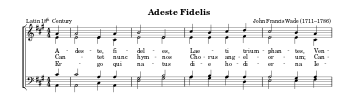

"O Come, All Ye Faithful" (originally written in Latin as Adeste Fideles) is a Christmas carol which has been attributed to various authors, including John Francis Wade (1711–1786), with the earliest copies of the hymn all bearing his signature, John Reading (1645–1692) and King John IV of Portugal (1604–1656).[1][2][3]

The original four verses of the hymn were extended to a total of eight, and these have been translated into many languages. The English translation of "O Come, All Ye Faithful" by the English Catholic priest Frederick Oakeley, written in 1841, is widespread in most English speaking countries.[2][4] The present harmonisation is from the English Hymnal (1906).[2]

An original manuscript of the oldest known version, dating from 1751, is held by Stonyhurst College in Lancashire.[5]

Tune

Besides John Francis Wade, the tune has been purported to be written by several musicians, from John Reading and his son to Handel and even Gluck, including the Portuguese composers Marcos Portugal or the king John IV of Portugal himself. Thomas Arne, whom Wade knew, is another possible composer.[6] There are several similar musical themes written around that time, though it can be hard to determine whether these were written in imitation of the hymn, the hymn was based on them, or they are totally unconnected.

Wade included it in his own publication of Cantus Diversi (1751). It was published again in the 1760 edition of Evening Offices of the Church. It also appeared in Samuel Webbe's An Essay on the Church Plain Chant (1782).

Lyrics (English text following Frederick Oakeley)

|

Adeste Fideles

|

| Problems playing this file? See media help. | |

Adeste fideles læti triumphantes, |

O come, all ye faithful, joyful and triumphant! |

There are additional Latin verses in various sources.[7] For example:

En grege relicto, humiles ad cunas, |

Stella duce, Magi Christum adorantes, |

Æterni parentis splendorem æternum |

Pro nobis egenum et fœno cubantem, |

Other versions:

Cantet nunc hymnos chorus angelorum

Cantet nunc aula cælestium,

Gloria in excelsis Deo!

Venite adoremus (3×)

Dominum.

Text

The original text has been from time to time attributed to various groups and individuals, including St. Bonaventure in the 13th century or King John IV of Portugal in the 17th, though it was more commonly believed that the text was written by an order of monks, the Cistercian, German, Portuguese and Spanish orders having, at various times, been given credit.

The original text consisted of four Latin verses, and it was with these that the hymn was originally published. John Francis Wade had written the hymn in Latin in 1744, and was first published in 1751.[2][8] The Abbé Jean-François-Étienne Borderies wrote an additional three verses in the 18th century; these are normally printed as the third to fifth of seven verses, while another, anonymous, additional Latin verse is rarely printed. The text has been translated innumerable times, but the most used version today is the English "O Come, All Ye Faithful". This is a combination of one of Frederick Oakeley's translations of the original four verses and William Thomas Brooke's of the three additional ones, which was first published in Murray's Hymnal in 1852. Oakeley originally titled the song “Ye Faithful, approach ye” when it was sung at his Margaret Church in Marylebone before it was altered to its current form.[6]

King John IV

The most commonly named Portuguese author is King John IV of Portugal. "The Musician King" (1604–1656, came to the throne in 1640) was a patron of music and the arts and a considerably sophisticated writer on music; in addition, he was a composer, and during his reign he collected one of the largest musical libraries in the world (destroyed in the 1755 Lisbon earthquake). The first part of his musical work was published in 1649. He founded a Music School in Vila Viçosa that 'exported' musicians to Spain and Italy and it was at his Vila Viçosa palace that the two 1640 manuscripts of the "Portuguese Hymn" were found. Those manuscripts predate Wade's eighteenth-century manuscript.[3] Among the King's writings is a Defense of Modern Music (Lisbon, 1649). In the same year (1649) he had a huge struggle to get instrumental music approved by the Vatican for use in the Catholic Church. His other famous composition is a setting of the Crux fidelis, a work that remains highly popular during Lent amongst church choirs.

Jacobite connection

The hymn has been interpreted as a Jacobite birth ode to Bonnie Prince Charlie.[9] Professor Bennett Zon, head of music at Durham University, claims that the carol is actually a birth ode to Bonnie Prince Charlie, the secret political code being decipherable by the "faithful" (the Jacobites), with "Bethlehem" a common Jacobite cipher for England and Regem Angelorum a pun on Angelorum (Angels) and Anglorum (English).[9] Wade had fled to France after the Jacobite rising of 1745 was crushed. From the 1740s to 1770s the earliest forms of the carol commonly appeared in English Roman Catholic liturgical books close to prayers for the exiled Old Pretender. In the books by Wade it was often decorated with Jacobite floral imagery, as were other liturgical texts with coded Jacobite meanings.[10]

Performance

In performance verses are often omitted, either because the hymn is too long in its entirety or because the words are unsuitable for the day on which they are sung. For example the eighth anonymous verse is only sung on Epiphany, if at all; while the last verse of the original is normally reserved for Christmas Midnight Mass, Mass at Dawn or Mass During the Day.

In the United Kingdom and United States it is often sung today in an arrangement by Sir David Willcocks, which was originally published in 1961 by Oxford University Press in the first book in the Carols for Choirs series. This arrangement makes use of the basic harmonisation from The English Hymnal but adds a soprano descant in verse six (verse three in the original) with its reharmonised organ accompaniment, and a last verse harmonisation in verse seven (verse four in the original), which is sung in unison.

This carol has served as the second-last hymn sung at the Festival of Nine Lessons and Carols in King's College, Cambridge, after the last lesson from Chapter 1 of the Gospel of John.

Recordings, film music and other arrangements

Numerous versions have been recorded by artists of various genres from all around the world:

- An instrumental version is played by a symphony orchestra inside the Carnegie Hall in the 1992 film Home Alone 2: Lost in New York, the song also appears in the 1989 film National Lampoon's Christmas Vacation".[11]

- As "Dagen är kommen", the song was recorded by Swedish female singer Carola Häggkvist on her 1999 Christmas album Jul i Betlehem.[12]

- Twisted Sister's singer Dee Snider has said the song inspired him to write the band's 1984 song "We're Not Gonna Take It".[13] The band also recorded "O, Come All Ye Faithful" on their 2006 Christmas album "A Twisted Christmas", arranged in the same style as "We're Not Gonna Take It".[14]

- In 2011, singer Mariah Carey has released a version of the song in English, and the second single taken from the album Merry Christmas II You.

- In 2011, Hillsong Worship released a version of the song entitled "O Come Let Us Adore Him", with added choruses. It was released in the EP Born Is the King and the album We Have a Saviour.

- In 2016, American a cappella act Pentatonix released a version of the song on their album A Pentatonix Christmas.

- In 2016, the original version in Latin (Adeste fideles) was included in the album Laura Xmas released by Italian singer Laura Pausini.

The Portuguese hymn

The hymn was known as the Portuguese Hymn after the Duke of Leeds in 1795 heard it being sung at the Portuguese embassy in London.[15] However, the translation that he heard differs greatly from the Oakeley-Brooke translation, and was over forty years after John Francis Wade had published the hymn in 1751.[2][8]

A different account of the story is that King John IV of Portugal wrote this hymn to accompany his daughter Catherine to England, where she married King Charles II.

The Sacred Harp hymn tune "Portuguese Hymn" in 9 11 11 meter with 7 7 10 refrain ("Hither Ye Faithful, Haste with Songs of Triumph")[16] is slightly different from the usual tune.

References

- ↑ Stephan, John (1947). "Adeste Fideles: A Study On Its Origin And Development". Buckfast Abbey. Archived from the original on 13 October 2007. Retrieved 1 October 2007.

- 1 2 3 4 5 LindaJo H. McKim (1993). "The Presbyterian Hymnal Companion". p. 47. Westminster John Knox Press,

- 1 2 Neves, José Maria (1998). Música Sacra em Minas Gerais no século XVIII, ISSN nº 1676-7748 – nº 25.

- ↑ "Frederick Oakeley 1802–1880".

- ↑ "The One Show films at Stonyhurst". Stonyhurst. 19 November 2014. Retrieved 16 December 2015.

- 1 2 Spurr, Sean. "O Come All Ye Faithful". Retrieved 4 December 2012.

- ↑ The Hymns and Carols of Christmas, Source for other five verses.

- 1 2 Don Michael Randel (2003). "The Harvard Dictionary of Music". p. 14. Harvard University Press,

- 1 2 "Carol is 'ode to Bonnie Prince'". BBC. 18 December 2008. Retrieved 18 December 2007.

- ↑ "News & Events : News". 'O Come All Ye Faithful' – Bonnie Prince Charlie and the Christmas Carol. Durham University. 19 December 2008. Archived from the original on 25 December 2008. Retrieved 21 December 2008.

- ↑ Ryan Glab (23 December 2015). "Best movie series: sequels, trilogies, and sagas, oh my!". Ryanglab. Retrieved 26 December 2015.

- ↑ "Jul i Betlehem" (in Swedish). Svensk mediedatabas. 1999. Retrieved 22 December 2010.

- ↑ Kris Vire (2 November 2014). "Dee Snider on his Rock & Roll Christmas Tale". Timeout. Retrieved 26 December 2015.

- ↑ Jim Slotek (16 November 2015). "Twisted Sister's Dee Snider set to wow audiences with 'Rock 'n' Roll Christmas Tale'". Toronto Sun. Retrieved 26 December 2015.

- ↑ Crump, William D., The Christmas Encyclopedia, 3rd ed, 2013

- ↑ The Sacred Harp, 1860, p. 223: Scores at the International Music Score Library Project

External links

| Latin Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

Media related to Adeste fideles at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Adeste fideles at Wikimedia Commons- Text, translations and settings of "Adeste fideles" in the Choral Public Domain Library (ChoralWiki)

- Free sheet music of "O Come, All ye Faithful" for SATB from Cantorion.org

- Adeste, Fideles – two 19th-century arrangements

- Original Latin and English translation